Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Análisis filosófico

versión On-line ISSN 1851-9636

Anal. filos. vol.39 no.1 Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires mayo 2019

ARTICULOS

On the Literal Meaning of Proper Names

Sobre el significado literal de los nombres propios

Nicolás Lo Guercio

IIF-SADAF-CONICET

nicolasloguercio@gmail.com

Abstract

One of the main arguments in favor of metalinguistic predicativism is the uniformity argument. The article discusses one of its premises, according to which the Being Called Condition gives the literal meaning of proper names. First, the uniformity argument is presented. Second, the article examines a challenge by Jeshion (2015a) and a recent response by Tayebi (2018). It is then argued that Tayebi’s response is unsound. Finally, two sets of facts are discussed, which provide independent evidence against the literal meaning thesis.

KEY WORDS: Semantics; Predicativism; Uniformity Argument.

Resumen

Uno de los principales argumentos en favor del predicativismo metalingüístico es el argumento de la uniformidad. El artículo discute una de sus premisas, de acuerdo con la cual la ‘Being Called Condition’ proporciona el significado literal de los nombres propios. En primer lugar, se presenta el argumento de la uniformidad. En segundo lugar, se discute el desafío lanzado por Jeshion (2015a) así como la respuesta proporcionada por Tayebi (2018). Se argumenta luego que la respuesta de Tayebi falla. Finalmente, se presentan dos evidencias independientes contra la tesis del significado literal.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Semántica; Predicativismo; Argumento de la uniformidad.

The Uniformity Argument

The recent literature in philosophy of language has seen a rebirth of the old debate between referentialism and descriptivism. Referentialism is philosophical orthodoxy; it maintains that proper names refer non-descriptively to objects and contribute only those objects to propositional content.1 On standard versions of this view (Kaplan 1989, Salmon 1986), sentences express structured propositions constituted by objects and predicates (or relations) arranged in a certain way. Thus, a bare occurrence of a proper name in argument position like (1) below,

(1) Diego is a billionaire

expresses a proposition constituted by the individual Diego and the property being-a-billionaire

i. <Diego, being-a-billionaire>

Referentialism has initial intuitive support because, as Kripke famously argued, it respects many semantic, modal and epistemic intuitions concerning examples like (1). There are other uses of proper names, however, which are less amenable to Referentialism:

(2) Every Alfred passed the course

(3) There are two Alfreds in the class

(4) Alfreds are usually intelligent

(5) An Alfred came to the meeting

(6) The Alfred I met is obnoxious

Utterances like (2)-(6) raise semantic intuitions different from (1). Intuitively the truth of, say, (2) depends on whether every individual called Alfred passed the course, rather than the vicissitudes of a specific Alfred. On the other hand, (2)-(6) reveal that proper names can appear as bare plurals as well as complements of definite, indefinite, quantifier and numeric determiners, in a way that parallels the behavior of typical common count nouns, which have a predicative meaning.

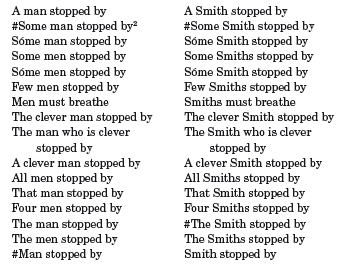

These facts led some linguists and philosophers (Sloat 1969, Burge 1973, Elbourne 2002, Matushansky 2008, Sawyer 2010, and Fara 2015a, among others) to propose an alternative approach, Metalinguistic Predicativism (MP), according to which proper names function as predicates in all of their occurrences, including apparently referential ones. This view rests, among other things, on the so-called uniformity argument, originally discussed in Sloat (1969) and Burge (1973), and recently brought back on the scene by Fara (2015a). The uniformity argument has both a syntactic and a semantic side. On the syntactic side, Sloat notes that proper names and common count nouns exhibit almost the same distribution with respect to different determiners (Sloat 1969, p. 27) – with some additions from Gray (2017):

As can be seen in the chart, there are only two mismatches between names and common count nouns: (i) names cannot appear in argument position with the definite determiner, while common count nouns can (in fact, the determiner is mandatory), (ii) common count nouns cannot appear in any referential position without a determiner, while proper names apparently must do so (I will qualify this below). As pointed out by Gray (2017, p. 432), there are two routes one could take in the face of these facts: one could either stick to the claim that proper names and common count nouns differ and try to explain away the overlap, or one could maintain that proper names are just common count nouns and try to explain away the differences. Predicativists take the second route, partly on account of its being more uniform. Concretely, predicativists claim that there is a very simple and parsimonious way of explaining away the problematic rows mentioned above while maintaining syntactic and semantic uniformity. If proper names are common count nouns, in order to appear as arguments, they must be flanked by additional material. For some defenders of MP, this is achieved by the definite article ‘the’ (Matushansky 2008, Fara 2015a) and for others, by the demonstrative ‘that’ (Burge 1973, Sawyer 2010). In this article I will be concerned with the former version of the view.

The key to uniformity then consists in stipulating that the English definite article possess a zero-allomorph and must be phonologically null when it is the sister of a proper name and it is not heavily stressed (see Fara 2015a, p. 93).3 Thus, for MP the structure of a sentence like‘Smith stopped by’ is the following:

[S[DP DET [NP Smith] [VP stopped by] ] (DET = /ø/)

where the determiner is the definite article ‘the’. If this is correct, both problematic rows above can be dealt with adequately and syntactic uniformity is preserved:

As can be seen in this new chart, on the MP analysis ‘The men stopped by’ matches ‘Smith stopped by’ (the definite article is phonologically null), while ‘#Man stopped by’ doesn’t really have a match, since there are no bare occurrences of proper names once we go beyond the superficial syntax.

On the semantic side, if names are common count nouns then they have a predicative meaning, hence they must have an application condition. Here I will concentrate on Fara’s (2015a, p. 64) rendition, the Being Called Condition:

Being Called Condition: A proper name ‘N’ is true of a thing just in case it is called N.4

Arguably, taking the meaning of proper names to be a metalinguistic predicate of this kind allows the predicativist to provide a semantically uniform account of all uses: on the one hand, the BCC straightforwardly takes care of examples like (2)-(6) above; on the other hand, referential uses of a proper name N are thought of as incomplete definite descriptions of the form ‘The N’ referring to the unique salient individual in the context called N. In addition, the thesis grants the predicativist an explanation of some attested patterns of inference (e.g.‘Alfred is hungry, therefore an individual called Alfred is hungry’) as well as the productivity and cross-linguistic uniformity of predicative uses.5

Arguably, syntactic and semantic uniformity is an advantage over referentialism: since referentialists (at least according to a certain characterization of the view) maintain that proper names are like individual constants in the lexicon,6 they are bound to hold that referential and predicative uses of proper names are both syntactically and semantically different. Moreover, they must provide an alternative explanation of the above-mentioned patterns of inference, and the productivity and systematicity of the relation between referential and predicative uses.

In what follows, I will discuss a challenge for the uniformity argument recently developed by Jeshion (2015a, b), as well as a possible answer by Tayebi (2018). In response to Tayebi, I will show first that there are some metasemantic considerations that allow the referentialist to avoid his criticisms. Then I will argue that some of the examples, which Tayebi discusses, are not only harmless for referentialism but in fact problematic for descriptivism. Finally, I will present some facts that provide independent evidence against predicativism, at least in its metalinguistic form.

Jeshion’s Challenge

Several authors (Boër 1975, Jeshion 2015a, b, Saab and Lo Guercio 2018) have called attention to various uses of proper names that do not elicit the metalinguistic reading brought into focus by predicativists. Here are some extensively discussed examples (Jeshion 2015a, pp. 371-372):

Family examples

(7) Joe Romanov is not a RomanovRepresentation examples

(8) Two Obamas came to the Halloween partyProducer examples

(9) Two Stellas are inside the museumResemblance examples

(10) Two little Lenas just arrived

Following Jeshion, I will call these examples Non-BCC-Friendly Examples. Now, in none of these cases, is the name intended to apply to individuals who bear that name. One prominent account of these predicative uses (see Fara 2015a, b and Matushansky 2015) treats them as cases of deferred interpretation, in the line of Nunberg (1995, 2004). Cases of deferred interpretation involve a salient functional relation between the thing (or things) alluded to in the deferred interpretation and the thing (or things) alluded to in the conventional meaning of the expression. To illustrate the point, consider one of the cases discussed by Nunberg (1995, p. 110):

(11) This is parked out back

If said by a speaker while handing over a car key to an attendant in a parking lot, (11)’s most natural interpretation is that the car is parked out back. The desired deferred interpretation is obtained in virtue of the existence of a salient functional relation between the car and the object being demonstrated, i.e. the car keys. Now, an explanation along these lines can be offered in order to account for some Non-BCCFriendly Predicative Examples. By way of illustration: a producer example could be explained as a case of deferred interpretation available in virtue of the existence of a salient functional relation between the things in the extension of the deferred interpretation of the expression, viz. the artworks made by Stella, and the things in the extension of the conventional interpretation of the expression, the unique individual salient in the context called Stella.

But if predicativists have a plausible account of these examples then what is the problem? The Non-BCC-Friendly examples serve to highlight an assumption that plays a crucial role in the uniformity argument, viz. that the Being Called Condition gives the literal meaning of proper names. Semantic uniformity is obtained by excluding uses of proper names, which do not accord with the BCC on account of these being non-literal, pragmatic interpretations. Without this assumption MP’s uniformity argument would be obviously problematic.

Jeshion (2015a, b) believes that this assumption can be challenged. The challenge consists in showing that one could account for the metalinguistic interpretation of proper names in the same way in which one accounts for Non-BCC-Friendly examples, namely as cases of deferred interpretation. The only difference is that, in this case, the input of the functional relation would not be uses of the name itself but mentions or quotations thereof. On her view, for example, Producer examples involve a use of a specific name, ‘Stella’, which refers to the famous painter Frank Stella. In that case, the functional relation is between the individual and the artworks produced by that individual. In turn, BCC-Friendly examples like

(12) Two Stellas are inside the museum

can be reinterpreted as involving a mention of the name as in (13)

(13) Two ‘Stellas’ are in the museum

In this case the salient functional relation in play would be between “individuals having a name with certain orthographic or phonological properties to that orthographic or phonological kind” (Jeshion 2015a, p. 382).7

This possibility threatens the uniformity argument: if BCCFriendly and Non-BCC-Friendly examples cannot be distinguished in terms of their literality, predicativism alleged methodological advantage in terms of uniformity vanishes. In light of this, predicativists seem to have the burden of proof: they need to substantiate the claim that the BCC gives the literal meaning of proper names.

Facing the Challenge: Tayebi’s Argument

Tayebi (2018) took up the challenge. The first step in his argument consists in showing that for each category of Jeshion’s Non-BCCFriendly Predicative Examples there are parallel Non-BCC-Friendly Referential Examples. Let’s see Tayebi’s cases (2018, pp. 11-12). First, Representation examples:

Context: suppose that there is just one guest at the party who is dressed like Obama. Intending to talk about him, the host says,

(14) Obama left the party very soon

According to Tayebi, whatever mechanism makes (8) – ‘Two Obamas came to the party’ – appropriate as a representation example, is the same mechanism at work in (14). Something similar can be said about Resemblance examples:

Context: My wife and I are wondering whether Lena’s only daughter, who looks exactly like Lena, will come to my daughter’s birthday party. Here is how my wife sets my mind at ease.

(15) Lena has arrived

Tayebi comments:

What makes an utterance of [(15)] appropriate in this situation is the contextually salient resemblance relation between the intended referent, i.e. Lena’s only daughter, and the conventional denotation of the name, i.e. Lena herself. This is exactly parallel to the mechanism that is at work in Jeshion’s predicative Resemblance Example of [(10)]. (Tayebi 2018, p. 11)

Here is Tayebi Referential Family example:

Context: the Association of Royal Families has a party in which just one descendant from each royal dynasty has participated in choosing the head. Walter Cox, about whom everyone at the party knows that he is never called Romanov, is attending on behalf of the Romanovs. It is after the polling that the manager, wondering about Cox’s vote, asks her assistant the utterance expressed in (16), and the assistant, in reply, utters (17):

(16) For whom did Romanov vote?

(17) Romanov didn’t vote at all.

Once again, this is a case in which ‘Romanov’ is used to refer to a particular individual, Walter Cox, who does not bear that name, and the reason for which the name can be felicitously used to refer to him is his relation to the Romanov dynasty, the same reason for which (7) above can be used in that way.

None of these examples can be accounted for by the predicativist in terms of the BCC. Predicativists must say then that these are nonliteral referential uses of proper names. Crucially, Tayebi claims that referentialists must also treat them as non-literal uses of proper names: since the referentialist claims that the semantic role of a proper name‘N’ is just to refer to N, she must treat the BCC-Friendly Referential Examples as literal and the Non-BCC-Friendly Referential Examples presented above as non-literal (cf. Tayebi 2018, p. 12).

Now, recall that Jeshion’s challenge consisted in urging the predicativist to show that BCC-Friendly Predicative Examples are literal, as opposed to Producer examples, Family examples, etc. Tayebi’s response to the challenge is to claim that whatever justification the predicativist has for claiming that BCC-Friendly Referential Examples are literal can be extended to BCC-Friendly Predicative Examples:

This is the case because, from the predicativist’s point of view, my referential Representation, Resemblance, and Family Examples have the same relation to the BCC-Friendly Referential Examples that Jeshion’s predicative Representation, Resemblance, and Family Examples have to the BCC-Friendly Predicative Examples (Tayebi 2018, p. 12)

To sum up, the strategy consists in showing that for each category of Jeshion’s Non-BCC-Friendly Predicative Examples there are parallel Non-BCC-Friendly Referential Examples, which the predicativist can justifiably treat as non-literal; moreover, these are examples that even the referentialist must treat as non-literal. If this is right, the predicativist is justified in her claim that BCC-Friendly Referential Examples are literal. But then, Tayebi argues, whatever the justification is for treating BCC-Friendly Referential Examples as literal, it can be extended to BCC-Friendly Predicative Examples. The reason is that the same relation that holds between BCC-Friendly and Non-BCC-Friendly Referential Examples holds, he argues, between BCC-Friendly and Non-BCC-Friendly Predicative Examples.

Tayebi believes that Producer examples are somewhat different from the rest. Specifically, he claims that in those cases it is not possible to generate Non-BCC-Friendly Referential Examples. To be sure, a sentence like (18)

(18) Stella is on the second floor

can only mean that a specific individual, Stella, is on the second floor. In order to convey that a specific artwork made by an artist called Stella is on the second floor you need the article, as in (19):

(19) The Stella is on the second floor

I believe Tayebi is wrong. In fact, it is possible to generate referential producer examples, e.g. ‘Picasso is on the second floor’ meaning that Picasso’s exhibition is on the second floor of the museum.8 He is right, however, in claiming that sentences like (19) are grammatical. This fact, however, is problematic for predicativism in general and for Tayebi’s defense in particular (more on this below).

The Literal Meaning of Proper Names

In the previous section we have discussed the way in which the predicativist can justify her treatment of BCC-Friendly Predicative Examples as literal. Roughly, the strategy was to show that the BCCFriendly/ Non-BCC-Friendly distinction can also be found in referential examples, and that whatever justification there is for treating the latter as non-literal we can extend it to the predicative case. In light of this argument, Tayebi concludes: “it is incumbent upon her opponent [the referentialist] to show why this justification cannot be extended to the predicative side of the parallelism, i.e. the BCC-Friendly/Non-BCCFriendly distinction in predicative cases”. In this section I will address Tayebi’s response. First, I will reject his claim that referentialists must treat Non-BCC-Friendly examples as non-literal. Second, I will present an argument against the thesis that whatever mechanism is present in the referential side can be extended to the predicative side of the parallelism. Finally, I will discuss two pieces of evidence that independently support the idea that the BCC does not give the literal meaning of proper names in referential examples.

Referentialism and literality

One of the problems with proper names is to give their individuation conditions. Do all Johns have the same name, or are there many different Johns, say, John1, John2, John3… and so on? According to the former view, proper names resemble indexicals (Recanati 1993, Pelczar and Rainsbury 1998) or pronouns (Schoubye 2016), since their semantic value varies with context. According to the latter view we have a different lexical entry for each John, so reference is stable. Now, one prominent account among those who adopt this latter view maintains that names are individuated by their origin (Kripke 1980, Sainsbury 2005). The idea is that in typical cases there is an original baptism, by means of which a subject attempts to associate a given phonological articulation, say /Obama/, with a specific individual. If everything goes well, a name-using practice comes into existence. Furthermore, baptisms metaphysically individuate the practice and thus fix the referent, so any name and name-using practice involves exactly one baptism. On this view, baptizing an object involves two steps: object-introduction and practice origination, which are independent in the sense that each can be successful while the other is not. Successful object-introduction occurs when the object being baptized accords with the intention of the baptizer (e.g. the owner of the boat crushes the bottle in the boat he had the intention to baptize). The intentions of the baptizer might be objectrelated (the intention is appropriately caused by direct interaction with the object itself) or descriptive, but even if the baptizer identifies the object descriptively; it is not the descriptive information that identifies the practice.9 Successful object-introduction need not suffice for bringing into existence a name-using practice though, for the name might not ‘catch on’ (e.g. if the name is never used again); whether a new name-using practice has been successfully introduced depends on what happens later.

Now, with this view in mind, we can go back to the Tayebi’s Non-BCC-Friendly Referential Examples. By way of illustration, consider representation examples like (14). Tayebi claims that even the referentialist has to admit that (14) contains a non-literal use of the proper name ‘Obama’: for a referentialist the only semantic contribution of a proper name is the referent, but it is clear that in the stipulated context the speaker of (14) is not alluding to its usual referent. To be sure, the referentialist view previously sketched admits the possibility of there being uses of ‘Obama’ which participate in the relevant nameusing practice but in which speaker reference and semantic reference differ, as long as this fact does not become common in the community of speakers. Crucially, though, the referentialist is not forced to describe the case in this way. More specifically, she can describe Non-BCC-Friendly Referential Examples as cases in which a new baptism takes place, thus a new name, or in the case of (14), a nickname, is introduced. On this view, the speaker has either an object-related or a descriptive intention which allows her to appropriately identify the referent in the context, and by means of which she manages to successfully introduce the object by calling him ‘Obama’. Does the speaker additionally initiate a new name-using practice? At this point the case is unspecified, but there are two alternatives. One possibility is that the name catches on. Suppose that the person dressed like Obama was someone known among the relevant social circle and the speaker, their friends, family, etc. start referring to him with the nickname ‘Obama’. In that case, a new nameusing practice has been created. The other possibility is that (14) is a one-off use; for some reason nobody follows the speaker in her attempt to initiate a new practice. Even then, though, the case could be described as an unsuccessful baptism, i.e. a case in which the speaker successfully introduced an object but failed at initiating the corresponding nameusing practice. Crucially, in both cases the referentialist is able to re-describe the situation in a way which is compatible with her view and that avoids talking of a non-literal referential use of a previously existent proper name.

Tayebi briefly considers this strategy, but expresses reservations concerning its plausibility. First, he observes that the strategy leaves unclear the reason why the speaker specifically chooses to use a phonologically and orthographically identical name to identify the referent instead of any other one. Second, he claims that given that we already need deferred interpretations in order to account for predicative examples, and that this same mechanism can be put to work for explaining alleged Non-BCC-Friendly Referential Examples,“it does not seem to be reasonable and well-motivated, methodologically speaking, to introduce a new and distinct mechanism to explain such examples. This would involve complicating our semantic theory beyond all necessity” (Tayebi 2018, pp. 16-17).

Concerning the first part, I believe the referentialist answer is pretty straightforward. Baptisms involve the introduction of an object, and this relies at least partly upon the intentions of the baptizer. Now, for the audience to correctly recognize the object that the speaker intends to introduce they need some contextual clues. In the case at hand, the speaker uses the name-like articulation /Obama/ because it evokes the name-using practice related to Barack Obama, thus bringing the specific referent associated with it into salience, and making the information associated with the name available in the context. These contextual clues, together with the common knowledge that one of the guests is dressed like Obama, allow the hearer to understand the descriptive intention of the speaker, thus recognizing the object which she is aiming to introduce. Choosing the name-like articulation /Obama/ might also have further ‘pragmatic’ advantages, like being funny, or triggering some desired inferences in the audience.

The second worry is also misplaced. In fact, the proposed explanation does not complicate the semantics at all: the semantic account of names remains a classically referentialist one. It might be argued that it does complicate the metasemantics, that is, the story concerning how to metaphysically individuate proper names.10 Admittedly, the referentialist’s metasemantic story is more complicated than the predicativist’s one. However, it is independently motivated by already known arguments as the ones developed by Kripke and Sainsbury, among others. Moreover, this strategy would make Tayebi’s defense of the uniformity argument depend upon a presumed advantage in terms of metaphysical simplicity, but whether this kind of considerations really favor predicativism over referentialism is a highly controversial issue, for which Tayebi provides no argument.

If this is correct, Tayebi’s strategy is undermined: the referentialist need not accept one of Tayebi’s premises, namely, that his Non-BCC-Friendly Referential Examples are non-literal uses of proper names. Instead, she could maintain that Non-BCC-Friendly Referential Examples are just attempts at introducing proper names (or, alternatively, nicknames) which might or might not catch on.

Different readings, different pragmatic processes

Let me begin this section by discussing Non-BCC-Friendly Producer Examples. In section §3 we saw that although Tayebi is wrong in that (18) does admit a Non-BCC-Friendly referential interpretation, he is right in that in (19) it is grammatical. Concerning the latter, I think Tayebi misses a fundamental point, namely that according to the predicativist, (19) should be ungrammatical. Recall Sloat’s chart in section §1: according to that chart, an occurrence of a proper name in argument position flanked by the overt definite article is ungrammatical. Tayebi’s example (19) shows that this is not always the case. Moreover, the problem is not circumscribed to Producer examples. In Representation, Resemblance and Family examples, although you may get a Non-BCC-Friendly referential reading without the overt definite article (as Tayebi shows), you can also obtain a grammatical result with the definite article. By way of illustration, consider the representation example (14) (repeated here as (20) for the sake of clarity):

Context: suppose that there is just one guest at the party who is dressed like Obama. Intending to talk about him, the host says,

(20) Obama left the party very soon

Granted, you get the Non-BCC-Friendly interpretation from (20). But you can also obtain it from (21), given the appropriate context.

Context: there is exactly one person dressed like Obama and exactly one person dressed like Reagan in the party

(21) The Obama left the party very soon, but the Reagan stayed.

These facts are surprising: according to MP, the definite article must be covert when it is the sister of a proper name in argument position and it is not stressed. However, ‘the N’ seems to be grammatical in argument position when the intended interpretation is the Non-BCCFriendly one.

To be sure, this is not just a minor point. The grammaticality of (19) threatens the whole syntactic rationale for the uniformity argument. Consider again the two rows of Sloat’s chart where proper names and common count nouns diverge:

![]()

If ‘the N’ is grammatical you get a match in the first row of the chart above, but you lose the motivation for positing a null determiner in bare occurrences. As Jeshion points out, the syntactic rationale for uniformity is contrastive and interdependent:

‘The Katherine sentences’ [namely, occurrences of proper names in argument position flanked by the overt definite article] standing as ungrammatical is indispensable to the Syntactic Rationale. There is no syntactic justification of [the thesis] Null Determiner: ‘the’ without it. It is the-predicativist’s chief data point against that-predicativism. It is their only data point incompatible with referentialist views on which predicative occurrences of “Katherine” are common count nouns. (Jeshion 2017, p. 227)

Put differently, if sentences like (19) are grammatical you lose the match in the second row, uniformity is lost and the argument falls apart (moreover, the mismatch appears exactly where it is expected to appear according to referentialists). Thus, inadvertently, Tayebi’s discussion points to a fundamental problem for the predicativist strategy.11-12

Be that as it may, I believe there is another problem with Tayebi’s argument, specifically with the claim that whatever mechanism explains the literal/non-literal distinction in the referential case can be extended to the predicative one. Tayebi claims that the mechanism that leads from BCC-Friendly Referential Examples to Non-BCC-Friendly Referential Examples is the same that leads from BCC-Friendly to Non-BCC-Friendly Predicative Examples. Now, consider on the one hand a BCC-Friendly Referential Example like

a. Obama left the party very soon [metalinguistic interpretation]

and on the other hand a Non-BCC-Friendly example both with and without the article

b. O bama left the party very soon [representation interpretation]

c. The Obama left the party very soon [representation interpretation]

For a predicativist, (b) and (c) are equivalent: first, they are supposed to have the same syntax ([DP DET [NP Obama]], DET = øthe), the only difference being that the definite article is null in (b); secondly, they are supposed to have the same literal semantics (given by the BCC); finally, we are stipulating that in this case they have the same nonliteral interpretation. Hence, according to predicativism the processes by which Non-BCC-Friendly examples like (b) and (c) are derived from BCC-Friendly example (a) should be the same.

However, there are good reasons to believe, pace predicativism, that (b) and (c) do not have either the same syntax or the same semantics. Regarding the former, as Saab and Lo Guercio (2018) show, referential and predicative occurrences of proper names differ crucially in their possibility of being pluralized:

d. The Obamas left the party very soon

e. #Obamas left the party very soon

This strongly suggests that only (c) possesses a number projection (see Saab and Lo Guercio for detailed discussion). In other words, the two constructions differ in their syntax.13

The semantic difference can be shown by noting that while ‘N’ in argument position can only be interpreted rigidly, ‘the N’ in the same position has a possible non-rigid reading. To see the point, consider the following sentences (keeping in mind the Non-BCC-Friendly interpretation):

(22) I could have seen Obama

(23) I could have seen the Obama

It is clear that you could utter (23) without a specific individual in mind.14 The point is this: if (b) and (c) differ both in their syntax and their semantics, then they cannot be generated from (a) in the same way. So the relation between (a) and (b) must be distinct from the relation between (a) and (c). Finally, note that according to the predicativist (who considers apparently referential cases as predicative) the relation between (a) and (c) is just the relation between a BCC-Friendly Predicative Example and a Non-BCC-Friendly Predicative Example. If this is correct, however, it seems that the relation between BCC-Friendly Referential Examples – (a) – and Non-BCC-Friendly Referential Examples – (b) – is different from the relation between BCC-Friendly Predicative Examples – for the predicativist, also (a)– and Non-BCC-Friendly Predicative Examples – (c) –.

The literal meaning of proper names

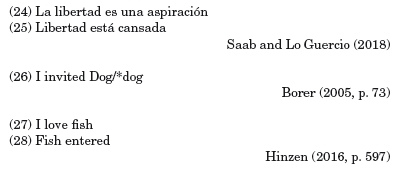

I would like to end by pointing to some independent reasons to resist the predicativist claim that the BCC gives the literal meaning of proper names, even assuming a predicativist view broadly construed. As Saab and Lo Guercio note, following Borer (2005, pp. 73-75) – see also Hinzen (2016) –, not only typical proper names can appear as common count nouns in predicative position, as in examples (2)-(6), but standard common count nouns can appear as proper names in argument position as well:

In examples like (25), (26) or (28), the common count noun interpretation is ungrammatical. The generalization that emerges from these facts is that common count nouns seem to lose all their descriptive meaning and acquire in turn a referential interpretation when they appear bare in argument position. This generalization undermines Tayebi’s argument. According to predicativism names are common count nouns with a metalinguistic interpretation, so given the previous generalization it is expected that when they appear bare in argument position they lose all their descriptive meaning and acquire just a referential interpretation. If this is correct, then standard uses of proper names in argument position do not have a literal metalinguistic meaning.15 One could maintain that proper names in particular do not lose their descriptive, common count noun interpretation when they appear bear in argument position. However, this seems ad hoc: metalinguistic predicativism owes us an explanation of this anomalous behaviour. If names are just common count nouns, why do they not behave as any other common count noun?

One could argue that the point made in the foregoing paragraph confuses the dialectics of the debate. Tayebi’s answer to Jeshion’s challenge assumes predicativism: it was designed to show that there are theoretic-internal reasons for the predicativist to maintain that the BCC gives the literal meaning of names. It seems however that the facts above mentioned, though relevant for the overall debate, only undermine Tayebi’s argument by undermining metalinguistic predicativism in general: both Saab and Lo Guercio, Borer and Hinzen use them to show that nouns are not predicative or referential per se but only as a function of the syntactic environment in which they appear. I think this charge is unjustified. To see why, note that there are versions of predicativism which, in principle, can handle the facts mentioned above. Consider the following passage from Elbourne (2002, pp. 185-186):

For the purposes of compositional semantics, however, such an account [namely, interpreting names as metalinguistic predicates] is not strictly necessary: […] Alfred has the denotation [λx. x is an Alfred], and it is no more necessary to do all the sociological (and other) groundwork about naming to use this lexical entry than it is necessary to undertake an extensive zoological project in order to use a lexical entry like [λx. x is a tiger].

That is, for Elbourne, predicativism need not commit with a particular interpretation of the predicate involved. To see the point consider Elbourne’s semantic representation of referential uses:

[[[DPThe 2 [NPAlfred ]] ]]=ιx[Alfred(x) and g(2)]

On his view, there is an extensional index that takes care of rigidity. One possible predicativist view is to maintain that the common count noun ‘Alfred’ in referential position has no descriptive meaning; all that matters is the value fixed by the assignment function g to the index. This would be undoubtedly a predicativist position, since it maintains that names are common count nouns with a predicative meaning. However, this view would honor the facts previously discussed, since it maintains that names, as any other common count noun, lose all descriptive meaning when they appear bare in argument position. If this is correct, then the argument sketched in previous paragraphs does not confuse the dialectics of the debate: the facts mentioned are not general facts against any predicativist proposal; they can be used specifically against metalinguistic predicativism and the uniformity argument. Even assuming predicativism, we have independent reasons to believe that the literal meaning of names in argument position is not given by the BCC.

There is further evidence pointing to the same direction. As originally noted in Sloat (1969) and many authors after him, in some cases names can appear as arguments in English with an overt definite article, viz. when followed by a restrictive relative clause, when anteceded by a nominal restrictive modifier, when heavily stressed or when accompanied by a deictic element:

(29) The Diego who won the world cup in 86’…

(30) I met THE Diego Maradona

(31) The old Diego got injured

(32) That Diego was a genius

However, in all these cases the meaning of the name differs from (1): in (29)-(32) we get a descriptive reading like the x such that x is a Diego, while in (1) we get just the referent, Diego.16 Now, as Hinzen (2016, pp. 594-595) points out, “the natural generalization, in short, is that what allows the presence of the determiner is that the reading is rich enough in terms of descriptive content”. That is why the definite article is allowed in cases (29)-(32), in which there is additional descriptive information, but not in (1), in which there is not. That also explains why the overt article is allowed with the Non-BCC-Friendly referential interpretation: there is a predicate in the context which is salient enough and by means of which the speaker intends to refer to a particular individual. In other words: definite descriptions need descriptive information, but names do not have that kind of information– at least not semantically coded, although they may presuppose it. As a consequence, you can’t have the latter with the definite determiner. In turn, when additional descriptive information is contributed by further structure or by context, the definite article is allowed, leading from a referential to a descriptive meaning.

This fact is relevant for the problem that concerns us. Even if you are a predicativist and you believe that bare referential uses of proper names are covert incomplete definite descriptions, the fact remains that adding the definite article leads systematically to a change in interpretation. This fact is easily explained if we grant that the name has no descriptive meaning when occurring bare in argument position. By contrast, such fact becomes puzzling if, as metalinguistic predicativism holds, the literal meaning of names in argument position is given by the BCC.17

Conclusion

One of the main arguments in favor of metalinguistic predicativism is the uniformity argument. I have presented the argument and examined its plausibility. Specifically, I consider one its premises, namely, the one that says that the BCC gives the literal meaning of proper names. After discussing Jeshion’s challenge and a possible response by Tayebi, I argued that Tayebi’s answer is insufficient. In addition, I discussed two independent facts which cast doubts about the thesis that the literal meaning of proper names is given by the BCC.

1 Referentialism is often sustained in tandem with at least two related (though different) theses: Rigidity, the view that a proper name’s reference is stable across possible worlds (Kripke 1980), and Direct Reference, the view that the reference of a name is not mediated by any propositional constituent (Kripke 1980, Salmon 1986).

2 Sloat considers both the unstressed ‘some’, typically associated with plurals and mass nouns, and the stressed ‘sóme’ usually represented by the existential quantifier.

3 Fara presents a mere generalization, without giving a principled explanation for these facts. I agree with Hinzen (2016, p. 596) that this approach is just a way of restating the problem. Matushansky, in turn, implements the same general strategy in a different way by appealing to a morphological rule called m-merger (Matushansky 2006, pp. 296-299). We cannot discuss Matushansky’s complex proposal in this article.

4 Fara’s BCC is not the only way of implementing the view. Some put forward a condition like “A proper name ‘N’ is true of a thing just in case it is called ‘N’”, where the last occurrence of N is in quotes (Kneale 1962, Geurts 1997). See Fara (2011) for discussion.

5 See Saab and Lo Guercio (2018) for further discussion. Also Hornsby (1976), Leckie (2013) and Schoubye (2016).

6 This is not the only way of characterizing the view though: indexicalists hold that proper names work like variables for individuals (see Recanati 1993, Pelczar& Rainsbury 1998, Cumming 1998 and Schoubye 2016), although on an indexicalist account the point above remains the same. It is important to note, however, that it can be argued that referentiality is not incompatible with syntactic complexity – see Saab and Lo Guercio (2018) and Predelli (2015).

7 Alternatively, if one is committed with a kaplanian metaphysics of names, one could say that the Non-BCC-Friendly examples involve a use of a specific or common currency name while the BCC-Friendly interpretation involves a generic name.

8 Thanks to Eleonora Orlando for this point.

9 Also, there might be both object-related and descriptive intentions involved in the baptism, and they need not select the same object. In these cases, if objectintroduction is to be successful, one of them must take precedence over the other.

10 Thanks to Eduardo García-Ramírez for raising this point.

11 Gray (2017) discusses a possible predicativist explanation of the grammaticality of ‘the N’ sentences which stipulates the existence of two different definite articles with a difference with respect to anaphoricity, one of which is overt, the other covert. This proposal is allegedly supported by data from languages like German (Schwartz 2009). It is not possible to properly assess the merits of such proposal in this article.

12 As Jeshion (2017) and Gray (2017) note, ‘the N’ construction is in fact grammatical, contrary to what has been commonly held. But to be sure, Jeshion’s examples are not BCC-Friendly Referential Examples with an overt definite article; crucially, in those cases the construction has a different meaning. I’ll discuss these examples in more detail below.

13 A predicativist like Matushansky could argue, against this point, that the difference is merely morphological. A full discussion of Matushasnky’s view is work for another article. Let me just state here that this wouldn’t explain the semantic difference pointed out below.

14 Admittedly, this is a complicated issue. Some predicativists like Geurts (1997) deny that names are rigid as a matter of semantics, and provide instead a pragmatic account of rigidity. Most predicativists, however, grant that there is a semantic difference with respect to rigidity between (apparently) referential examples and predicative examples and try to account for this difference within their position. Elbourne (2002), for example, argues for the existence, in referential examples, of an index that gets its value from an assignment function and behaves extensionally, that is, “The index in these structures will be used, on normal occasions of use, for picking out the particular bearer of the proper name in question that we want to say something about.” (Elbourne 2002, p. 225) Matushansky (2008) incorporates a variable for naming conventions in the lexical entry for proper names, which behaves extensionally in referential uses. Fara, in turn, argues that bare occurrences of proper names in argument position are incomplete definite descriptions, and those are rigid in context (that is, they might change they reference in context, but once the referent is fixed, they behave rigidly) I basically agree with Schoubye’s (2016) arguments against these proposals. On the one hand, Elbourne and Matushansky’s strategy of introducing a variable which behaves extensionally only in referential cases seems ad hoc. On the other hand, against Fara’s view: (i) it is simply not true that incomplete definite descriptions behave always rigidly, and (ii) if non-rigid readings of incomplete definite descriptions are always role-type descriptions in the sense of Rothschild (2007), then role-type readings of proper names should be available (and as easy to get as role-type interpretations of incomplete definite descriptions), which is not the case.

15 This is neutral with respect to whether there is a descriptive metalinguistic content conveyed in some other way, e.g. as a semantic presupposition (García-Carpintero 2017).

16 This much even the predicativists must accept. Recall fn. 13: Elbourne, Matushansky and Fara all stipulate some mechanism by means of which the alleged definite description manages to select a specific individual extensionally, in order to account for semantic intuitions concerning referential examples.

17 Here a similar remark as before is appropriate: this fact could in principle be accounted for by some form of predicativism like Elbourne’s view, so it is not just a general argument against predicativism but an argument against metalinguistic predicativism as well as against the uniformity argument.

References

1. Boër, S. E. (1975), “Proper Names as Predicates”, Philosophical Studies, 27 (6), pp. 389-400.

2. Borer, H. (2005), In Name Only. Vol. 1 of Structuring Sense, Oxford, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

3. Burge, T. (1973), “Reference and Proper Names”, The Journal of Philosophy, 70 (14), pp. 425-439.

4. Cumming, S. (2008), “Variabilism”, Philosophical Review, 117 (4), pp. 525-554.

5. Elbourne, P. (2002), Situations and Individuals, Boston, Massachusetts, PhD. Dissertation, MIT. [ Links ]

6. Fara, D. G. (2011), “You can call me “stupid”… just don’t call me stupid”, Analysis, 71, pp. 492-501.

7. Fara, D. G. (2015a), “Names are Predicates”, Philosophical Review, 124 (1), pp. 59-117.

8. Fara, D. G. (2015b), “‘Literal’ Uses of Proper Names” in Bianchi, A. (ed.) On Reference, Oxford, Oxford University Press, pp. 251-279.

9. García-Carpintero, M. (2017), “The Mill-Frege Theory of Proper Names”, Mind, 127 (508), pp. 1107-1168.

10. Geurts, B. (1997), “Good News about the Description Theory of Names”, Journal of Semantics, 14 (4), pp. 319-348.

11. Gray, A. (2017), “Names in Strange Places”, Linguistics and Philosophy, 40 (5), pp. 429-472.

12. Hinzen, W. (2016), “Linguistic Evidence against Predicativism”, Philosophy Compass, 11 (10), pp. 591-608.

13. Hornsby, J. (1976), “Proper Names: A Defence of Burge”, Philosophical Studies 30 (4), pp. 227-234.

14. Jeshion, R. (2015a), “Referentialism and Predicativism about Proper Names”, Erkenntnis, 80 (2), pp. 363-404.

15. Jeshion, R. (2015b), “Names not Predicates”, in Biachi, A. (ed.), On reference, Oxford, Oxford University Press, pp. 223-248.

16. Jeshion, R. (2017), “’The’ Problem for the-Predicativism”, The Philosophical Review, 126 (2), pp. 219-240.

17. Kaplan, D. (1989), “Demonstratives”, in Almog, J., Perry, J. y Wettstein, H. (eds.), Themes from Kaplan, Oxford, Oxford University Press, pp. 481-563.

18. Kneale, W. (1962), “Modality de dicto and de re”, in Nagel, E., Suppes, P. y Tarski, A. (eds.), Logic, Methodology and the Philosophy of Science: Proceedings of the 1960 International Congress, Palo Alto, Stanford University Press, pp. 622-633.

19. Korta, K. and Perry, J. (2011), Critical Pragmatics: An Inquiry into Reference and Communication, New York, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

20. Kripke, S. (1980), Naming and Necessity, Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

21. Leckie, G. (2013), “The Double Life of Names”, Philosophical Studies, 165 (3), pp. 1139-1160.

22. Matushansky, O. (2006), “Why Rose is the Rose: On the Use of Definite Articles in Proper Names”, Empirical Issues in Syntax and Semantics, 6, pp. 285-307.

23. Matushansky, O. (2008), “On the Linguistic Complexity of Proper Names”, Linguistics and Philosophy, 31, pp. 573-627.

24. Matushansky, O. (2015), “The Other Francis Bacon: On Non-BARE Proper Names”, Erkenntnis, 80 (2), pp. 335-362.

25. Nunberg, G. (1995), “Transfers of Meaning”, Journal of Semantics, 12 (2), pp. 109-132.

26. Nunberg, G. (2004), “The Pragmatics of Deferred Interpretation”, in Horn, L. and Ward, G. (eds.), Blackwell Encyclopedia of Pragmatics, pp. 344-364.

27. Pelczar, M. and Rainsbury, J. (1998), “The Indexical Character of Names”, Synthese, 114 (2), pp. 293-317.

28. Predelli, S. (2005), Contexts: Meaning, Truth, and the Use of Language, Oxford, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

29. Predelli, S.(2015), “Who’s Afraid of the Predicate Theory of Names?” Linguistics and Philosophy, 38 (4), pp. 363-376.

30. Recanati, F. (1993), Direct Reference: From Language to Thought, Blackwell. [ Links ]

31. Rothschild, D. (2007), “The Elusive Scope of Descriptions”, Philosophy Compass, 2 (6), pp. 910-927.

32. Saab, A. and Lo Guercio, N. (2018), “No Name: The Allosemy View”, Studia Linguistica. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/ stul.12116.

33. Sainsbury, R. M. (2005), Reference without Referents, New York, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

34. Salmon, N. U. (1986), Frege’s Puzzle, Cambridge, The MIT Press.

35. Sawyer, S. (2010), “The Modified Predicate Theory of Proper Names”, in Sawyer, S. (ed.), New Waves in Philosophy of Language, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 206-226.

36. Schoubye, A. J. (2016), “Type-ambiguous Names”, Mind, 126 (503), pp. 715-767.

37. Schwartz, F. (2009), Two Types of Definites in Natural Language, Boston, Massachusetts, Ph.D. thesis, University of Massachusetts Amherst. [ Links ]

38. Sloat, C. (1969), “Proper Nouns in English”, Language, 45 (1), pp. 26-30.

39. Tayebi, S. (2018), “In Defense of the Unification Argument for Predicativism”, Linguistics and Philosophy, 41 (5), pp 557-576.

Received 11th November 2018; revised 25th March 2019; accepted 3rd April 2019.