Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista argentina de cirugía

Print version ISSN 2250-639XOn-line version ISSN 2250-639X

Rev. argent. cir. vol.113 no.2 Cap. Fed. June 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.25132/raac.v113.n2.1500.ei

Articles

Splenic cyst. Laparoscopic partial splenectomy with vascular exclusion

1 Sanatorio Trinidad. Quilmes. Buenos Aires. Argentina.

2 Sanatorio de la Trinidad. Ramos Mejía. Buenos Aires. Argentina.

Introduction

For years, spleen disorders were managed with splenectomy until, in the seventies, a retrospective study of 2,796 patients undergoing splenectomy reported infections or sepsis in 119 (4.25%) and, of these, 71 (60%) died1.

Although previous techniques designed to preserve splenic function, such as the implantation of tissue in the greater omentum maintain tissue vitality and hemopoietic function, the immune function is not equally preserved; thus, this has been an unresolved issue until recently2-4.

Partial splenectomy is nowadays an unusual indication either by conventional approach or laparoscopy, that is not standardized; however, it is the best option to maintain the immune function.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the outcomes of partial splenectomy with vascular occlusion in adult patients with splenic cysts.

Material and methods

Between May 2016 and May 2019, patients undergoing laparoscopic partial splenectomy due to splenic cysts were selected from a retrospective database of Sanatorio Trinidad Quilmes and Sanatorio Trinidad Ramos Mejía.

The indication for surgery was the presence of symptomatic spleen cysts.

All patients underwent routine laboratory tests, with determination of carcino embryonic antigen and Ca 19-9, immunological test to rule out hydatid disease, ultrasound and contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan to visualize the distribution of spleen vascularization.

Laparoscopic partial splenectomy for cyst resection was indicated in all the cases, as described in a previous publication3.

The patient was positioned supine and then rolled 45° to the right, with the right arm extended to place an intravenous line for infusion of fluids and intraoperative medications. The left arm was fixed over the patient’s head.

The surgeon and assistant stood to the patient’s right with the scrub nurse on the patient’s left. The tower for laparoscopy was placed on the left of the patient’s head.

The Veress needle was introduced through the site of the optical trocar, 4 cm below the left costal margin in the mid-clavicular line. Pneumoperitoneum pressure was set at 12 mm Hg and the rest of the trocars were introduced under direct vision. A 5-mm trocar was inserted in the middle point of the line between the umbilicus and xiphoid process. A 10-mm trocar was placed in the mid-axillary line, below the costal margin and another 5-mm trocar was placed in the posterior axillary line.

The surgery started with ligation of the short vessels; in one patient, this step was followed by dissection of the splenic vein and splenic artery, immediately before its bifurcation. A Vessel loop® was used to encircle the artery and was clipped for fixation. A stay suture was placed in the splenic vein without occluding the lumen to avoid venous engorgement of the spleen. In another patient, the superior vascular trunk was ligated first and then the inferior vascular trunk was clamped, while the vessels were not clamped in the other two patients.

The gastrosplenic ligament was partially divided to maintain the attachment of the preserved segment of the spleen and prevent postoperative splenic torsion.

Then, the parenchyma was transected using high frequency bipolar electrosurgical scalpel, Ligasure® (Covidien).

Once transection was completed, fine hemostasis of the bed was performed in 3 patients with monopolar electroscalpel (spray coagulation) and with argon plasma coagulation in one. Finally, hemostasis was verified releasing the vessels clamps. A drain was left in the surgical bed and passed through the 5-mm trocar of the left lumbar region.

The specimen was placed in a bag and extracted through a 5-mm incision at the level of a Pfannenstiel-like scar of a previous cesarean section. In the remaining three patients, a similar incision was made in the left hypochondriac region. The cysts were evacuated to facilitate the extraction.

All the patients were evaluated with contrast-enhanced CT scan and scintigraphy one month after surgery.

Results

In 3 patients, discomfort in the left hypochondriac region, left lumbar region or subcostal region was the predominant symptom; the definitive diagnosis was made by ultrasound and CT scan.

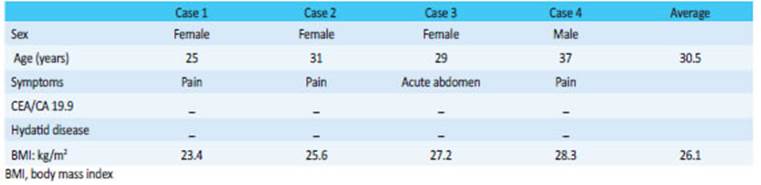

One patient with acute abdomen presented with pain in the subcostal region and left hypochondriac region associated with nausea. Physical examination revealed tenderness and guarding in the hypochondrium without rebound pain. The laboratory tests were normal, and the ultrasound and computed tomography scan showed a 10 × 9 cm cyst in the superior pole of the spleen. As intracystic hemorrhage was suspected, the patient was followed up and monitored with a favorable outcome and surgery was scheduled 20 days later (Table 1).

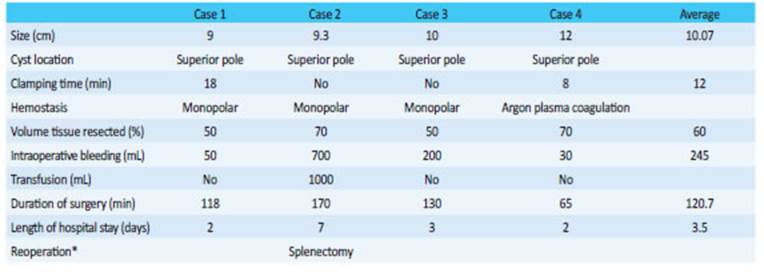

There were no conversions; one patient underwent reoperation 36 hours later due to bleeding and required total splenectomy by the conventional approach (Table 2).

The histological examination reported epidermoid cyst in all the cases.

All the patients were monitored between 15 days and one month after surgery with CT scan, with adequate distribution of the contrast agent. A scintigraphy performed later showed adequate uptake of the preserved spleen.

Discussion

The role of the spleen in the regulation of circulating blood volume, hematopoiesis, immunity, and protection against infections and malignancies is well known4.

Spleen resection is associated with high risk of infections, particularly in the lungs. The risk of sepsis after splenectomy is higher within the first two years, and ranges between 4.25% and 18.2%, 200 times greater than that of the general population; 60% of them will die1-4. In addition, the probability of atherosclerotic events, pulmonary hypertension and thrombosis has been reported5,6. Therefore, if preservation of part of the spleen is feasible, partial splenectomy seems reasonable.

While the minimally invasive approach for total splenectomy is well established, this is not the case for partial splenectomy, with information arising from single case reports, or case series, retrospective studies meta-analyses including few patients8,9.

Partial splenectomy is indicated in some hematological diseases (hereditary spherocytosis and hemoglobin diseases), benign tumors (cysts, hemangiomas, lymphangiomas, fibromas), hydatid disease, disorders of uncertain histology, acute complications such as rupture or subcapsular hematoma and more rarely in metastatic tumors especially of gynecologic cancers7-9.

Spleen preservation, clinical follow-up and selective embolization are well established indications for splenic rupture. Yet, selective embolization can fail and is associated with complications as abscess, spontaneous rupture and post-embolization syndrome, characterized by fever, pain and vomiting. Therefore, in those cases where surgery is necessary, the best option is open or laparoscopic partial splenectomy.

To understand the rationale for partial splenectomy, it is necessary to have a thorough knowledge of the anatomy, segmentation and irrigation of the spleen with its variants.

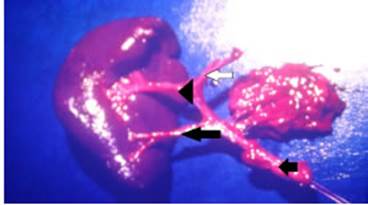

D.I. Liu et al. performed a study of the anatomy of the spleen in 850 specimens, and found a single lobar artery in 0,8%, 2 lobar arteries in 86% and 3 in 12.2%. These lobar arteries are divided in the organ to define 5 segments in most cases, 6 or 7 on rare occasions and exceptionally 8 segments10 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Surgical specimen showing the splenic artery (short black arrow) with its branches. Superior lobar artery (arrowhead) and inferior lobar artery (long black arrow). Both arteries divide to supply blood to 4 segments: short vessel (white arrow). A portion of the pancreas tail is observed

Recently, Balaphas et al. from Geneva, Switzerland, have described a classification based on the irrigation of the splenic remnant, and divided it into 4 types: a) irrigation of the remnant pole through the upper hilar branch, b) irrigation through the lower hilar branch, c) irrigation of the remnant upper pole through the short vessels, d) irrigation of the lower pole through the left gastro-epiploic branch7.

Campos-Christo performed the first splenic segmentectomy in humans in Minas Gerais, Brazil, in 1959, with the participation of DiDio, Neder y Zappala, an anatomist. Three years later, this author published the details and results of this procedure through open approach11.

The first case of laparoscopic partial splenectomy due to trauma was reported by Poulin in 1995. Later, in 2001, Smith published the results of two patients with splenic cysts treated with a conservative approach: one patient was treated with marsupialization of the cyst and the other with hemisplenectomy12,13.

The risk of intraoperative or postoperative bleeding, and ischemia and necrosis in case of inadequate blood supply are barriers to partial resection.

The risk of hemorrhage can be minimized by controlling the vascular pedicle as the initial gesture, and then performing parenchymal transection with instruments that use ultrasonic or high-frequency energy to provide hemostasis, argon plasma coagulation, mechanical stapler, radiofrequency, etc.16. It is preferable to start by ligating the vascular branch of the segment that will be resected and then clamp the branch of the segment that will be preserved, to reduce ischemia time.

Temporary circulatory exclusion of the organ appears to be a feasible and safe option; however, although the tolerance of ischemia is unknown, the longer time required (18 minutes) did not result in impairment of the preserved segment with complete anatomical and functional recovery. On the contrary, the two patients in whom this gesture was not performed presented intraoperative bleeding; one of them developed hemoperitoneum and required reoperation to complete the splenectomy.

In 2011, Patrzyk et al. published the results of partial splenectomy with total vascular exclusion in 3 patients using a detachable laparoscopic clamp, without mentioning the clamping time. Mean operative time was 144 minutes with optimal functional outcomes15.

Preservation of 25-30% of splenic parenchyma is adequate to ensure satisfactory function. When the remnant parenchyma is small, it is advisable to attach it.

Many techniques have been used to minimize bleeding, as absorbable mesh splenorrhaphy, fibrin-based or cellulose-based hemostatic agents; radiofrequency ablation and mechanical stapler14.

Introperative small intestine injury has been mentioned as a complication of partial splenectomy. The incidence of postoperative complications is 5.36% and includes left pleural effusion, ischemia of the remnant segment, splenic vein thrombosis, fever and ischemia, diarrhea, pain of unknown origin and subphrenic abscess. About 3% require postoperative transfusion7,8.

The conversion rate has been reported between 2 and 3.6%, generally due to difficulties to control intraoperative bleeding7. The procedures can be converted to total splenectomy by laparoscopy or open surgery, open partial splenectomy or hand-assisted partial splenectomy8.

Recently, Bas et al. performed laparoscopic partial splenectomy in a patient with hydatid cyst that was erroneously interpreted as a simple cyst. During surgery, they found many adhesions to the omentum, stomach, abdominal wall and diaphragm that interfered with the procedure. Before attempting conversion, the procedure was successfully completed using hand-assisted laparoscopic technique through a 6-cm subxhiphoidal incision9-18.

Cystic lesions have been managed with percutaneous aspiration with or without sclerosis, total or partial cystectomy, marsupialization, or plication. These techniques are no longer used due to the high number of complications and recurrences.

In 2008, Palanivelu et al. reported their experience in a series of 11 patients treated with either marsupialization, plication or partial cystectomy with a mean follow-up of 29.5 months. Two patients of the 3 who underwent marsupialization (18.2%) had cyst recurrence after 14 months16. In a series of 38 patients undergoing partial splenectomy published by Uranues et al., in 20 patients the indication for surgery was a cyst; 4 had recurrent cysts after deroofing procedures17.

In 2007, Meterns et al. presented a 12-year experience (from October 1989 to November 2001), with 15 patients with splenic cysts who underwent spleen preserving surgery by laparotomy in 9 patients and by laparoscopy in 6. Eight patients underwent partial splenectomy and cyst decapsulation and omentoplasty was performed in 7. Mean follow-up was 37.5 months; 4 patients (57.1%) who underwent decapsulation presented recurrent cysts with a mean diameter of 3.5 cm (1 in a primary cyst and 3 in secondary or posttraumatic cysts)18.

Referencias bibliográficas /References

1. Schwartz PE, Sterioff S, Mucha P, Melton III LJ, Offord KP. Postsple nectomy Sepsis and Mortality in Adults. JAMA. 1982; 248:2279- 83. [ Links ]

2. Pisters PW, Pachter HL. Autologous splenic transplantation for sple nic trauma. Ann Surg.1994; 219:225-35. [ Links ]

3. Minetti AM, Martínez JE, Pitaco JI, Gómez E, Adami C. Esplenecto mía parcial con exclusión vascular mediante abordaje laparoscó pico. Rev Argent Cirug. 2016:108. [ Links ]

4. Karup PF. Postsplenectomy infections in danish children splenec tomized 1969-1978. Acta Pediatr Scand. 1983; 72:589-95. [ Links ]

5. Hassn AM, Al-Fallouji MA, Ouf TI, Saad R. Portal vein thrombosis following splenectomy. Br J Surg. 2000; 87:362-73. [ Links ]

6. Schilling RF. Spherocytosis, splenectomy, strokes and heart attacks. Lancet. 1997; 350:1677-80. [ Links ]

7. Balaphas A, Buchs NC, Meyer, J, Hagen ME, More P. Partial sple nectomy in the era of minimally invasive surgery: the current la paroscopic and robotic experiences. Surg Endosc. 2015; 29:3618- 27. [ Links ]

8. Gangshan Liu, Ying Fan. Feasibility and Safety of Laparoscopic Partial Splenectomy: A Systematic Review. World J Surg. 2019; 43:1505-18. [ Links ]

9. Bas G, Alimoglu O, Sahin M, Uranues S. Laparoscopic partial sple nic resection in hydatid disease. Eur Surg. 2009; 41:90-3. [ Links ]

10. Liu DL, Xia S, Xu W, Ye Q, Gao Y, Qian J. Anatomy of vasculature of 850 spleen specimens and its application in partial splenectomy. Surgery. 1996; 119:27-33. [ Links ]

11. Marcelo Campos Christo M, DiDio LJA. Anatomical and surgical aspects of splenic segmentectomies. Ann Anat. 1997;179: 461- 74. [ Links ]

12. Poulin EC, Thibault C, DesCôteaux JG, Côté G. Partial laparoscopic splenectomy for trauma: technique and case report. Surg Lapa rosc Endosc. 1995; 5:306-10. [ Links ]

13. Smith ST, Scott DJ, Burdick JS, Rege RV, Jones DB. Laparoscopic marsupialization and hemisplenectomy for splenic cysts. J Lapa roendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2001; 11:243-9. [ Links ]

14. Héry G, Becmeur F, Méfat L, Kalfa D, Lutz P, Lutz L, Guys JM, Lagau sie P. Laparoscopic Partial Splenectomy: Indications and results of a multicenter retrospective study. Surg Endosc. 2008; 22:45- 9. [ Links ]

15. Patrzyk M, Glitsch A, Hoene A, von Bernstorff W, Heidecke CD. Laparoscopic partial splenectomy using a detachable clamp with and without partial splenic embolization. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2011; 396:397-402. [ Links ]

16. Palanivelu C, Rangarajan M, Madankumar MV, John SJ. Lapa roscopic Internal Marsupializaton for Large Nonparasitic Splenic Cysts: Effective Organ-Preserving Technique. World J Surg. 2008; 32(1):20-5. [ Links ]

17. Uranues S, Grossman D, Ludwig L, Bergamaschi R. Laparoscopic partial splenectomy. Surg Endosc. 2007; 21:57-60. [ Links ]

18. Mertens J, Penninckx F, DeWever I, Topal B. Long-term outcome after surgical treatment of nonparasitic splenic cysts. Surg Endosc. 2007; 21:206-8. [ Links ]

text in

text in