Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista argentina de cirugía

Print version ISSN 2250-639XOn-line version ISSN 2250-639X

Rev. argent. cir. vol.114 no.2 Cap. Fed. June 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.25132/raac.v114.n2.1576

Articles

Complex bile duct injury. Conservative management

1 Unidad de Cirugía Hepatobiliar Compleja y Trasplante Hepático. Hospital El Cruce. Buenos Aires. Argentina.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is considered the standard of care for cholelithiasis. Despite technique refinement, technological improvement, imaging tests and preoperative assessment, the incidence of bile duct injury (BDI) has increased with this approach. De Santibañes et al. described complex BDIs as those injuries that involve the hepatic duct confluence, with failed repair attempts, associated with a vascular injury and portal hypertension or primary biliary cirrhosis1. These injuries constitute a challenge for the definitive repair. We report the case of a complex BDI with emphasis on the importance of a rapid referral and management in specialized centers.

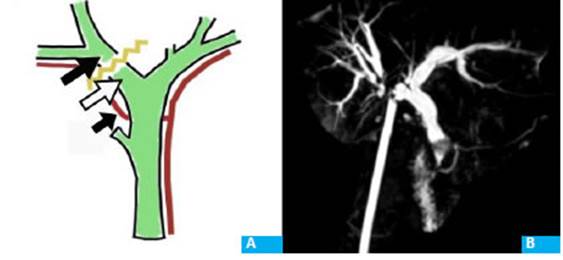

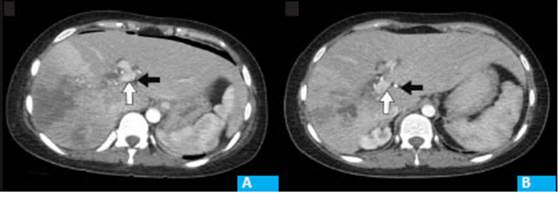

A 27-year-old female patient was admitted in other center with acute pancreatitis. Once the initial episode resolved, a cholecystectomy was scheduled. The procedure started through laparoscopy. We were unable to contact the surgical team; therefore the information obtained is the one detailed in the operative protocol, which described the presence of a cholecystoduodenal fistula complicated with massive bleeding during its repair. The procedure was converted to open surgery; the Pringle maneuver was used and hemostatic sutures were placed for bleeding control. Once the hemostasis was completed, two small orifices with bile outflow were identified. Two fine drains were placed in the orifices and an accessory drain was left in the foramen of Winslow (Fig. 1A). The patient was referred to our center on postoperative day 5, hemodynamically stable and without fever, with an approximate output of 100 mL from each biliary drain and 300 mL from the one in the foramen of Winslow. Laboratory tests on admission: hematocrit 32%, white blood cell count 16,300/mm3, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 969 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 1900 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 436 IU/L, total bilirubin (TB) 0.8 mg/dL and prothrombin time (PT) 74%. A magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography showed complete section of the proximal right bile duct at the level of the hilum corresponding to a Stewart-Way class IV injury, and the presence of a gallstone in the distal common bile duct (Fig. 1B). The triple-phase computed tomography scan showed significant hypoperfusion of the liver corresponding to the territory of the right portal vein and right hepatic artery, which were not visualized in their intrahepatic portion. There were no fluid collections or free abdominal fluid (Fig. 2A). In this case, we did not perform fistulography to evaluate the biliary tract to avoid contamination of the liver parenchyma involved. Watchful waiting was decided as bile leaked along the course of the catheter, there were no signs of infection, the hepatic function was preserved, and the patient’s clinical status was appropriate. On postoperative day 7 the patient presented fever due to surgical site infection; a sample was taken for culture and adequate treatment was initiated. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 14. Early referral allowed for a strict fluid and electrolyte balance and adequate caloric intake from the beginning, without the need for supplementary feeding, preserving the patient’s nutritional status. Follow-up continued in an outpatient basis. The output of the drain placed in the foramen of was 300 mL/day. The biliary output through the drains decreased progressively until they were removed. A new CT scan showed atrophy of the right lobe, hypertrophy of the left lobe and absence of abdominal fluid collections (Fig. 2B). The patient remained asymptomatic, with favorable outcome. She was readmitted three months later for fever due to urinary tract infection that was satisfactorily treated. The output from the foramen of Winslow decreased progressively and the drain was removed. For months after surgery the patient underwent scheduled endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and the common bile duct stone was successfully removed. Initially, we performed laboratory tests every month, and contrast-enhanced CT scan and magnetic resonance imaging every three months, alternately, during the first year. Thereafter, the patient was followed up every six months with laboratory tests and Doppler ultrasound. The patient has been monitored for 3 years and has not presented recurrences so far.

Figure 1 Site of the injury at the proximal right hepatic duct. A. Drains placed in the pro ximal right bile duct (black arrow), distal right bile duct (white arrow) and foramen of Winslow (short black arrow). B. Magne tic resonance cholangiopancreatography showing common bile duct lithiasis and the level of the injury.

Figure 2 Computed tomography scan on postope rative day 5 (A) and at 6 months (B). The segments of the left liver are hypertro phied, with marked hypoperfusion and progressive atrophy of the right liver seg ments, The white arrow shows the portal vein and the black arrow, the left hepatic artery. The right portal vein and right he patic artery cannot be identified.

Major vascular injuries during cholecystectomy usually correspond to Strasberg E4-E5 injuries or Stewart Way class IV2. Most series have reported an incidence of major vascular injuries of 8%. The right hepatic artery is the vascular structure most commonly injured (90%), followed by the common hepatic artery (8%) and the portal vein (4%). Portal vein injury usually occurs during cholecystectomy with catastrophic intraoperative bleeding, leading to untimely maneuvers3. Early complications associated with vascular injury include parenchymal necrosis with or without infection. Bile duct strictures, intrahepatic duct lithiasis, repeated cholangitis and hepatic atrophy may develop later. Fibrosis and even secondary biliary cirrhosis with portal hypertension may occur during long-term follow-up1,4. Lobe atrophy may be the consequence of vascular occlusion generally of the portal vein, prolonged biliary stricture, or a combination of both2. Resection is indicated in case of liver atrophy and intrahepatic bile duct strictures which may cause cholangitis or abscesses3-5. Defining the ideal timing of surgery is crucial; it is currently accepted to treat the initial foci of infection and postpone the definitive procedure to evaluate the progression of ischemia. It has been shown that early repair does not yield favorable results6.

Conservative management of complex BDIs, as in this case, is not the most usually used approach and requires a series of conditions: absence of necrosis and infection in the hepatic lobe involved, absence of other septic complications such as cholangitis and abscesses, presence of bile leaks from the drainage and integrity of the rest of the biliary tract. For this reason, in our case we decided to postpone ERCP until achieving atrophy of the segment, thus avoiding biliary contamination via the ascending route and the possibility of generating abscesses. Early contact and referral to a specialized, high-volume center is the best decision, achieving the best results in solving the problem, with low rate of complications and higher survival.

Referencias bibliográficas /References

1. de Santibáñes E, Ardiles V, Pekolj J. Complex bile duct injuries: Management. Hpb. 2008;10(1):4-12. [ Links ]

2. Strasberg SM, Helton WS. An analytical review of vasculobiliary injury in laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy. Hpb. 2011;13(1):1-14. [ Links ]

3. Wang Z, Yu L, Wang W, et al. Therapeutic strategies of iatrogenic portal vein injury after cholecystectomy. J Surg Res. 2013;185(2):934-9. [ Links ]

4. Pekolj J, Yanzón A, Dietrich A, Del Valle G, Ardiles V, De Santibañes E. Major liver resection as definitive treatment in post-cholecystectomy common bile duct injuries. World J Surg. 2015;39(5):1216-23. [ Links ]

5. Truant S, Boleslawski E, Lebuffe G, Sergent G, Pruvot FR. Hepatic resection for post-cholecystectomy bile duct injuries: A literature review. Hpb. 2010;12(5):334-41. [ Links ]

6. Pottakkat B, Vijayahari R, Prasad K V, et al. Surgical management of patients with post-cholecystectomy benign biliary stricture complicated by atrophy-hypertrophy complex of the liver. Hpb. 2009;11(2):125-9. [ Links ]

Received: March 10, 2021; Accepted: May 13, 2021

text in

text in