Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista argentina de cirugía

Print version ISSN 2250-639XOn-line version ISSN 2250-639X

Rev. argent. cir. vol.115 no.1 Cap. Fed. May 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.25132/raac.v115.n1.1618

Articles

Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas (Frantz tumor) in a 13-year-old girl

1 Sanatorio Juan XXIII de General Roca. Río Negro. Argentina

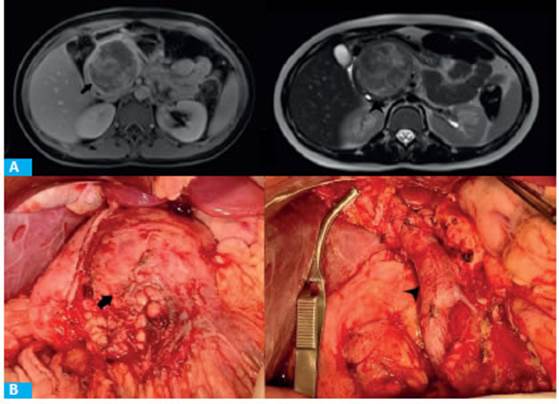

Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas (SPT) is also known as Frantz tumor after Dr. Virginia Frantz, who was the first to describe it in 1959. It is also known as Hamoudi’s tumor, papillary cystic neoplasm or solid-cystic papillary neoplasm, in reference to its two most important histologic elements: the solid and pseudopapillary areas. SPT is a rare neoplasm with a low malignant potential and represents 1- 3% of all pancreatic tumors1. They usually occur in women with a female to male ratio of 10:1 and primarily affect women between 20 and 30 years of age but is also common in the pediatric population with an incidence of 0.005-0.01 cases per 100 000 inhabitants1. The most common location is the tail of the pancreas (33-80%), followed by the head (32-67%), body (14-27%) and uncinate process (3%). Surgical resection offers the possibility of an excellent long-term survival. A 13-year-old girl visited the emergency department due to abdominal pain in the right hypochondrium radiating to the back, nausea and vomiting lasting 5 days. On physical examination, there was a mass in the right hypochondrium and periumbilical region, slightly tender on palpation. The laboratory tests and tumor markers were within normal ranges. The abdominal ultrasound showed a large heterogeneous mass measuring 65 × 60 mm between the pancreas and the retroperitoneum. On computed tomography (CT) scan, an irregular, heterogeneous mass of 10 × 8 cm was observed arising from the head of the pancreas, with heterogeneous vascularization during the portal phase and some cystic lesions in the head of the pancreas. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed the previous findings and revealed heterogeneous hypervascularization in the arterial and portal phases and external compression of the main pancreatic duct. The superior mesenteric artery (SMA), celiac trunk (CT), common hepatic artery (CHA) and portal vein (PV) were free of tumor (Fig. 1A). Since this was a complicated lesion with no signs suggestive of malignancy and the patient did not have social security coverage, we decided not to use endoscopic ultrasound in this case so as not to delay treatment of the disease. The patient was admitted to the local acute care hospital and was referred to the private system for surgery 48 hours later. The procedure was performed via a Chevron incision. An encapsulated hypervascularized mass arising from the head of the pancreas was visible. The mass displaced the portal vein (Fig. 1B). There was also a 4-cm hematoma between the inferior margin of the neck of the pancreas and the portal vein (possibly the cause of abdominal pain). A cephalic pancreaticoduodenectomy was performed and the Machado technique (double loop) was used for reconstruction. Operative time was 240 minutes. The patient was extubated in the operat88 ing room and was admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit for 48 hours. Spinal anesthesia with bupivacaine 0.125% and fentanyl 0.25 mcg/kg/h was administered through an epidural catheter under daily monitoring by an anesthesiologist. Patient-reported pain was 3 points on a 0-10 points rating scale. The ERAS protocol was implemented, with early mobilization, initiation of liquid diet and domperidone 20 drops every 8 hours 12 hours after the procedure (according to the protocol applied to CPD in adults). The urinary catheter was removed 48 hours later and soft diet was initiated. The patient was transferred to the general ward on postoperative day 3 and the epidural catheter was removed. A sample was taken from the abdominal drain to measure amylase levels, and as they were negative for pancreatic fistula, the catheter was removed. The patient had favorable postoperative outcome and was discharged with oral ketorolac, esomeprazole and domperidone. A visit to the outpatient clinic was scheduled for 4 days later, with follow-up visits every 4 months. She was also controlled by the diabetes care clinic and her glucose levels are currently normal. A stool elastase test was requested; the amount of elastase was >300 μg/g, ruling out the diagnosis of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency.

FIGURE 1 A: MRI showing heterogeneous mass with hyperintensity in T1 weighted image during portal phase (black arrow) and hypointensity in T2 (arrowhead). B: Tumor mass (black arrow). Surgical bed, the portal vein is exposed (arrowhead)

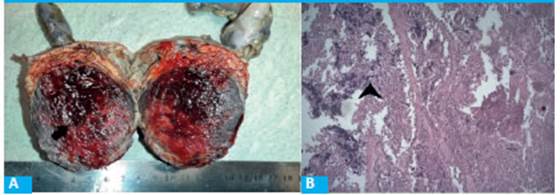

Pathological study: the head of the pancreas measured 9 × 8 × 6 cm and had a brownish, hemorrhagic tumor of 7 × 6 cm with clear borders. The tumor was friable and presented several foci of hemorrhage and submassive ischemic necrosis with vascular structures and pseudopapillary formations surrounded by cells with hyperchromatic and small nuclei (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2 A: Well-delimitated axial transection of the tumor (black arrow). B: Submassive necrosis. HE staining (arrowhead)

Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas is a rare tumor which typically affects adolescent girls and young women. and is traditionally described as an epithelial tumor with pseudopapillary and cystic features on gross examination. The diagnosis is generally made after episodes of abdominal pain or is an incidental finding during imaging test procedures2. The imaging tests recommended are transabdominal or endoscopic ultrasound, CT scan or MRI. The CT scan shows a circumscribed and heterogeneous mass, with solid and cystic components and hypervascularization in the portal and arterial phases. Magnetic resonance imaging reveals hyperintensity of the solid component in T1 weighted images, more intense in contrast-enhanced images, and hyperintensity of the cystic component in T2-weighted sequences3. SPTs have been classified in 1996 by the World Health Organization as tumors with low-grade malignant potential. The prognosis is excellent, with a 1-year and 5-year survival of 90% and 78%, respectively4,5. Surgical resection is the treatment of choice. Approximately 40% of lesions present have calcifications, which are best visualized with CT scan. Although < 50% present hemorrhagic areas, the presence of hemorrhage is a feature that distinguishes solid-pseudopapillary tumor from other pancreatic tumors in which hemorrhage is even rarer6.

The clinical presentation is unspecific and the diagnosis is usually incidentally made during imaging test procedures. Patients usually present with abdominal or back pain, abdominal bloating, nausea and vomiting, palpable abdominal mass and weight loss. However, they may be asymptomatic in 28-80% of cases1. The surgical approach of SPT may be through open surgery or laparoscopy. The technique used depends on the tumor site. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomies are usually performed for tumors of the body and tail of the pancreas and pancreaticoduodenectomies for tumors of the head and neck. In selected cases, enucleation is feasible when the tumor size is around 2-3 cm. The long-term prognosis of SPT, is favorable with excellent survival at 5 years or greater in more than 95% of patients undergoing surgery5,6.

Referencias bibliográficas /References

1. Berrada G, et al. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: a rare entity in children. Pan Afr Med J. 2020; 35:137. [ Links ]

2. Minh Xuan N, Khanh Tuong T, Quang Huy H. A Rare Case of Large Solid Pseudopapillary Tumor in a Child. Am J Case Rep. 2020;21: e923990. [ Links ]

3. Gandhi D, et al. Solid pseudopapillary Tumor of the Pancreas: Radiological and surgical review. Clin Imaging. 2020; 67:101-7. [ Links ]

4. AlQattan A, et al. Huge solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas ‘Frantz tumor’: a case report. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2020; 11(5): 1098-104. [ Links ]

5. Yang F, Fu D. ASO Author Reflections: A Novel Classification System to Predict Outcome in Solid Pseudopapillary Tumor of the Pancreas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020; 27(3): 757-8. [ Links ]

6. Zou C, et al. Ki-67 and malignancy in solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pancreatology. 2020; 20(4): 683-5. [ Links ]

Received: September 14, 2021; Accepted: November 19, 2021

text in

text in