Introduction

College students represent an important subpopulation of the United States, with over 14 million students in the US enrolled in public colleges and universities, and 5 million students enrolled in private institutions.1 They are a diverse yet unique subgroup with very singular health risks and health needs.

Health status is periodically assessed through the National College Health Assessment (NCHA). This survey includes domains of health habits, behaviors, and perceptions.2 Mental health disorders have been frequently assessed in college students. In 2019, NCHA II showed that around 19% of the assessed students were ever diagnosed for depression. Of those diagnosed, 73% contacted a healthcare or mental health provider within the last 12 months.3

Nevertheless, there is little published data about mortality and causes of death in the college population. In 2010, Turner et al. reported on mortality data from 202 institutions of higher education over a 10-year period. The five leading causes of death by proportion were accidents (26.3%), suicide (8.0%), heart and circulatory diseases (7.7%), pneumonia (7.3%) and tuberculosis (6.4%).4 Between 1920 and 1955 Parrish collected causes of death at Yale University. His results also showed the main cause were accidents (43.8%) followed by suicide (12.0%).5 Other historical data also suggests that suicide is the second leading cause of death among students at American colleges and universities.6,7 When comparing this with the national data, the leading causes for 20-24 age group are accidents (42.3%), intentional self-harm (16.9%) and assault or homicide (15.5%).8 This data includes both college students and their non-college peers.

National Death Index

The National Death Index (NDI) is a centralized database of death record information on file in state vital statistics offices. Working with these state offices, the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) established the NDI as a resource to aid epidemiologists and other health and medical investigators with their mortality ascertainment activities.9 The NDI operates in the National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). NDI provides an official underlying cause of death and multiple cause of death fields referred to as “entity-axis codes” and “record-axis codes”.

The University of Wisconsin-Madison

The University of Wisconsin-Madison (UW) is a large public research university in the Midwest United States with a total fall 2018 enrollment of 44 411.7 There

are 13 schools and colleges offering multiple undergraduate, master's, and doctoral degree programs.10 In 2018, 68.4% of enrolled students were undergraduates, 51.3% were female, 14.2% were international students, and 67.1% were white.11

The purpose of this study was to analyze the causes of death based on death certificate data, of students enrolled at UW-Madison from 2004 through 2018.

Methods

We undertook a descriptive analysis of the causes of death for all deceased students reported by the UW Dean of Students Office (DSO) between 2004 and 2018. We analyzed frequencies and yearly rates, calculated as average number of cases per average population in the analized period amplified by 100.00. UW-Madison’s University Health Services (UHS) received 150 reports of deceased students (potential cases) from DSO in that time period. Of those, 57 students did not meet our definition of a case and were excluded from further analysis. Cases per year were collapsed in five-year periods in order to minimize individual identification. A sample dataset of 93 deceased students was created using key identifiers and submitted to the, National Death Index (NDI) for matching and to obtain the official “underlying cause of death”, “entity-axis”, and “record-axis” codes. We received matching data for 89 students, which then comprised our sample for analysis. Demographics and academic data was obtained from the UW-Madison enrollment system. This is an IRB expempted proposal and it was approved by the NDI.

Case definition and inclusion criteria

Students were included in the analysis if they:12

1. Were enrolled in classes during the term in which they passed away (i.e., passed away after the published start date of the current semester and before published graduation date), or

2. Attended classes in the fall, spring, or summer term directly before their passing and were enrolled in classes for the upcoming semester.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded persons for whom we could not confirm enrollment at UW-Madison during the time period, or whose death occurred after the UW's published graduation date for the previous term that they were enrolled in, and for which there was no indication of continued enrollment.

Students with incomplete data about their enrollment status and dates were excluded from the analysis.

Students who were enrolled but passed away abroad were also excluded. Death certificates for US Citizens who die abroad is obtained in a different manner including consular offices of the country involved. Death certificates of those UW-Madison international students dying abroad cannot be obtained.

Students who did not match to a person in the National Death Index (NDI) data were also excluded.

Group definitions

The cause of death analyzed was the one provided the National Death Index (NDI) when a case matched. The code analyzed for cause of death is called “underlying cause of death”.13 The underlying cause of death is defined as “(a) the disease or injury which initiated the train of events leading directly to death, or (b) the circumstances of the accident or violence which produced the fatal injury”.

Because some causes of death are unique and identifiable, we grouped the underlying causes of death into three main groups:

-Intentional self harm cause of death includes all those causes of death that the death certificate defines as intentional by self-harm. This category includes death by suicide but excludes homicide/assault.

-Vehicle accidents includes all causes involving any type of vehicle and were the cases where either a pedestrian, driver or occupant non-driver was involved in a collision or accident.

-Other category includes all other causes of death including infections, cardiovascular events, cancer, accidental poisoning, and unknown cause of death.

Results

Whole sample and quinquennial intervals

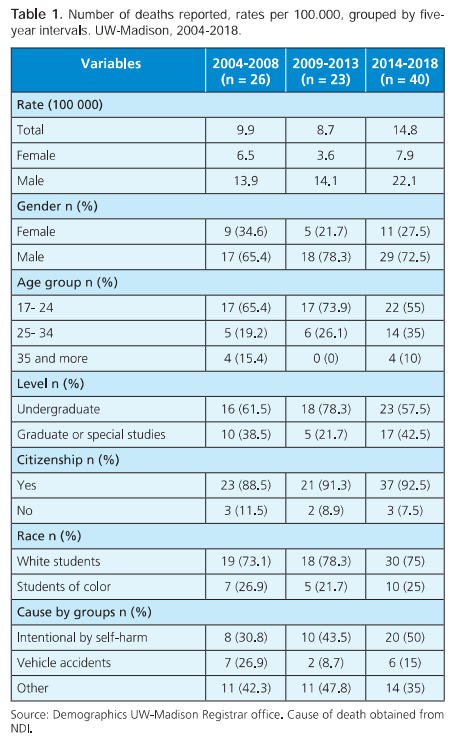

Table 1 shows that of the 89 cases, 72% (64) were male and 28% (25) were female. Most of the sample were domestic students (91%, n = 81) whereas the rest were international students. Over 73% (n = 63) of the cases were classified as white. Undergraduates represent 64% (n = 57) of the sample whereas graduates, professional or special students were 36% (n = 32) Students under 24 years of age represented almost 63% (n = 56) of the sample.

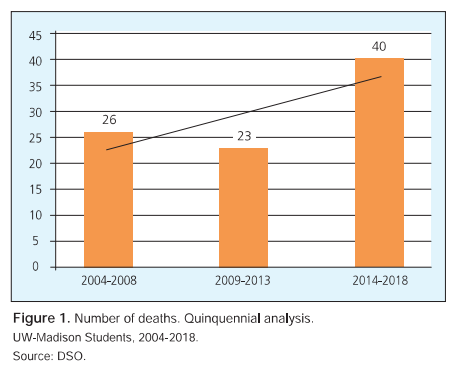

When considering the quinquennial periods total cases increased almost 54% when comparing first and last period showing a growing trend (Figure 1). Total mortality rate increased, specially due to male mortality rate increasing from 13.9 per 100 000 in the first quinquennial to 22.1 in the last one. There is an increasing trend when analyzing Intentional by self-harm cause of death over the years and for “other” causes of death over the years. There is a mild decreasing trend when we analyze vehicle accidents. Intentional deaths increased 150% from the first to the last analyzed period (20 vs 8) and “other” causes of death increased 27% (14 vs 11); On the other hand, vehicle accidents decreased 14% (7 vs 6) when considering first and last period.

Analysis per group

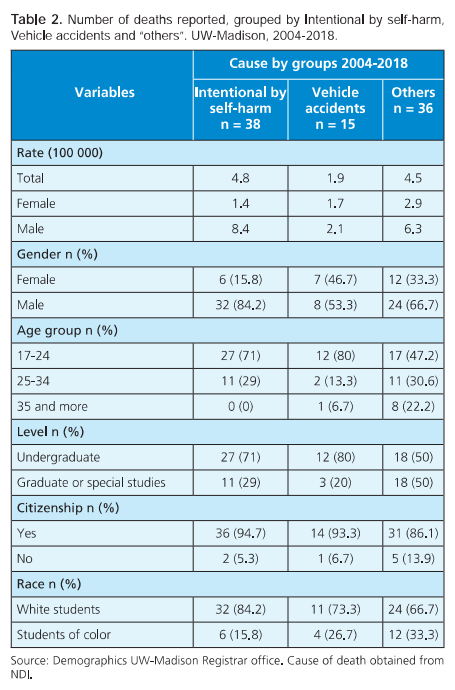

Rates per year and cause for the entire 2004-2018 period show 4.8 per 100 000 for intentional causes by self-harm, 1.9 per 100 000 for vehicle accidents and 4.5 per 100 000 for “other” causes of death. The rate difference between male and female per group was 7 per 100 000 students for intentional causes by self-harm, 0.4 per 100 000 students for vehicle accidents and 3.4 per per 100 000 students for “other” causes of death.

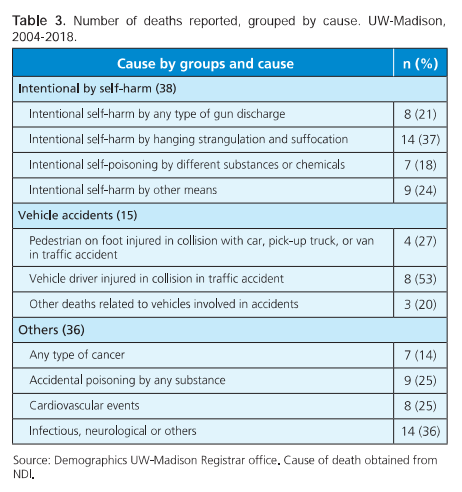

We observe most of the deaths, 43% (n = 38), were intentional by self-harm. When analyzing groups of causes by sex, we observe 50% of males (n = 32) died of intentional by self-harm causes whereas 48% of females (n = 12) died of “other” causes. The youngest age group (ages 17-24) had the highest proportion of intentional by self-harm deaths (48%), whereas the oldest age group (age 35 plus) had a higher proportion of “other” (89%) as cause of death (Table 2). Undergraduates had a higher proportion of intentional by self-harm deaths (47%). Consistently, graduates and other students show most of their deaths related to other causes (56%). Students of color are less likely (27%) to have intentional by self-harm causes of death than White students (48%). For students of color most of their deaths fall under the category of “others” (55%).

Analysis per cause

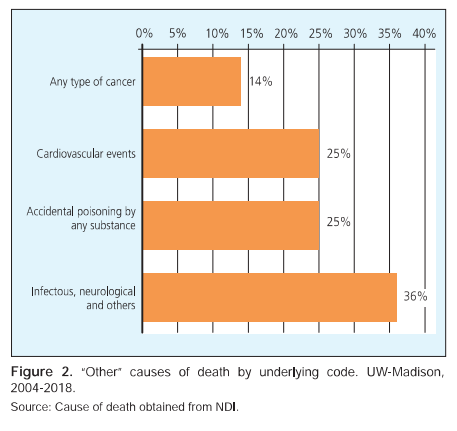

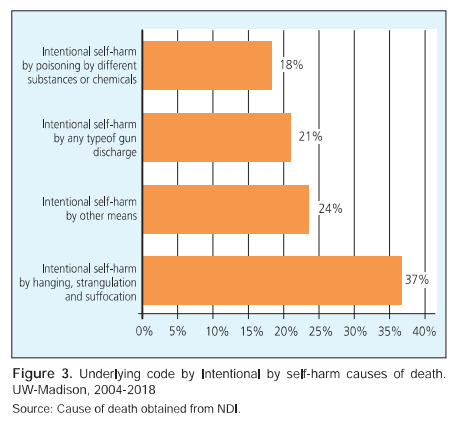

“Accidental (unintentional) poisoning and exposure to different substances” including unspecified drugs, medications and biological substances, alcohol, narcotics or psychedelics represent 10% (9/89) of all causes of death and almost 27% (9/36) of the causes within the “other” group. Cardiovascular events also represent 10% (9/89) of all causes of death and almost 27% (9/36) of the causes within the “others” group. Malignant events are around 6% (5/89) of total causes of death and 22% (8/36) within the “other” group. Almost 15% (13/89) of causes distribute between infectious events, neurological and others, including unknown cause of death. All of them are included in the “other” group (Figure 2). For intentional causes of death, “Intentional self-harm by hanging, strangulation and suffocation” as the underlying code represents around 38% (14/38) of the intentional by self-harm group and 16% of all deaths (Figure 3). Drivers of any type of vehicle, including cars, truck, motorcycles, pedal cycles, represent almost 9% (8/89) of the total causes of death and 53% (8/15) of the vehicle accidents.

Substance related cause of death

When adding all causes of deaths related to legal or illegal substance use/misuse/poisoning, 18% (16/89) of our whole sample has either the underlying code or the other causes of death fields related to the use of one or more substances (When the case included multiple substances involved in the entity and record axis codes, they were included in the substance related analysis). Accidental poisoning by and exposure to different substances as underlying cause of death represent 10% (9/89) of our total sample. Multiple substances were involved in 8 of the 9 cases. Alcohol was identified in nearly 6% (n = 5) of the deaths, including intentional by self-harm and accidental poisoning categories, with a rate of 0.63 per 100 000. All these five cases have at least one other substance other than alcohol in the indirect cause of death. Heroin or cocaine were included in almost 7% (n = 6) of the cases, both intentional by self-harm and accidental. Antidepressants were involved in nearly 6% (n = 5) of the deaths, both intentional by self-harm and accidental.

Discussion

Our analysis shows that total mortality rate and male students mortality rate increased whereas mortality in female students seem to remain stable over the analyzed periods. The increment of total deaths over the analyzed periods is at expense mainly of self-harm causes. In line with these findings, the National Survey of College Counseling Centers survey performed in 2013 highlighted that 95% of the directors assessed, reported increase over the past five years in self-injury issues, illicit drug and alcohol use, crisis response requirements, among others.13 Locally, UW-Madison UHS data shows that between 2017 and 2019, mental health clients increased 35%, crisis response encounters increased 33% and psychiatric visits in almost 20%.14,15 The self-harm mortality rate overall and by gender from our data aligns with Schwartz’s mortality rates of overall suicide rates where overall self-harm mortality rate of 4.8 per 100 000/4.3 per 100 000, female self-harm mortality rate of 1.4 per 100 000/2 per 100 000 and male self-harm mortality rate of 8.4 per 100 000/7.1 per 100 000.6

Unlike prior published data where accidents were reported as the more prevalent cause of death in college students, our analysis shows the main cause of death between 2004 and 2018 was intentional by self-harm deaths.3

Younger people have higher proportion of accidental and self harm deaths. As school level typically aligns with age, undergraduates also a higher proportion of intentional by self-harm deaths.16 According to CDC, unintentional injuries and suicide are the leading cause of death for age group 15-24.17

When analyzing by race or ethnicity, it is difficult to generalize given the small numbers of deaths by different racial groupings. However, when grouping race and ethnicity, we see that students of Color are less likely to have intentional by self-harm causes of death and more likely to fall under the category of “others” whereas White students were more likely to have died by intentional by self-harm causes of death. Several studies align with these findings showing African American college students have better coping and survival skills than their European American counterpeers.18 However, some other studies show the opposite when considering suicide or suicide attempts, where students of Color had significant higher prevalence.19,20

When considering the underlying code or the way the intentional by self-harm took place, we observe 37% of these deaths occurred by hanging. This data is similar to the 32% found in the National Survey of College Counseling Centers, 2013.13

Substances, including alcohol were involved in almost 2 out of 10 deaths. Literature shows mortality related to substance use among college students is increasing in the U.S.21 Historically high risk drinking, directly injuries and deaths was reported by over 40% of College students.22 Recent research show similar percenages.23 Local UW-Madison data showed almost 39% students of color and 57% of White students had reported high risk drinking patterns.24

Prevention implications

Our analysis shows intentional by self- harm deaths (suicides) lead all causes and may also be underestimated due to incomplete information available about some “other” causes. This points to an opportunity to prevent a significant portion of student deaths overall by implementing indicated suicide prevention strategies.

Findings in our analysis can point prevention practitioners to opportunities to tailor means restriction for campus. Means restriction is a set of strategies employed to reduce access to common means (methods) of suicide attempts and self-harm on campuses. Most suicidal crises are short-lived,25,26 and restricting access to lethal means is an effective strategy to reduce suicides and accidental deaths.27

A comprehensive approach to reducing the risk of suicide on a college campus includes means restriction. The first crucial step that universities should take when implementing means restriction is gathering campus-specific information. In gathering information, campus should review data (such as this report) on fatalities to identify causes of death, means used and trends.13

Means restriction is one element of a broader suicide prevention strategy, but this element’s impact can extend beyond suicide prevention to also prevent accidental deaths and injuries.

Limitations

The analysis only includes deaths reported by the Dean of Students Office. These deaths were often noticed to the university by family members, the academic community, peers, or other sources. Students who die during a term are more likely to be reported in university records; if a student dies after the term has ended it is possible the university would not be informed of the death. We were conservative in our estimate as we excluded students who may have intended to come back to school but had not yet enrolled in classes. In addition, the university does not follow up on enrolled students that withdraw within a semester to determine their status. There are no legal requirements for reporting a death to the university.

Intentional by self-harm causes of death may be underestimated. Several “accidental poisoning and exposure” underlying cause of death included multiple substances. These cases could be interpreted as suicide but were not assigned an intentional by self-harm cause of death code in the NDI.

The small sample size makes it difficult to obtain meaningful outcomes when analyzing demographics or other subgroup characteristics.

Further analysis, including an evaluation of excess of mortality in selected demographics is needed.

Future proposals

We continue to collect data from DSO locally, and plan to develop a systematic way of contacting enrolled students that do not return to classes in a subsequent term.

We suggest scaling the present proposal to all UW System campuses to have a more robust data set. We also propose creating a data repository that will include mortality data of different universities across the country. We could analyze how this data compares to our data. We could also compare student deaths to those in the general national college age population.

This data as well as further analysis will be used to inform, support, and evaluate campus-wide prevention strategies for means restriction and environmental safety.