Introduction

Biodiversity conservation

Over the past 50 years, the prevailing view of biodiversity conservation has changed, from a conservation think ing focused on “nature for itself”, going through paradigms of “nature despite people”, and “nature for people”, un til the most recent “people and nature” approach (Mace, 2014). The last view guided the assessments of the Intergov ernmental Science Policy Platform for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IP BES), focused on the concept of “nature’s contributions to people” (Díaz et al., 2018; Mastrángelo et al., 2019), which embraces a variety of worldviews on human nature relations and knowledge systems (Pascual et al., 2017).

The last assessments of the IPBES (Brondizio et al., 2019) highlight that the rate of global biodiversity change during the past 50 years is unprecedented in hu man history (Díaz et al., 2019). But even in this alarming scenario, nature can be conserved and used sustainably while simultaneously meeting other global so cietal goals. Since the Convention on Bi ological Diversity (CBD, United Nations, 1992), until the most recent Sustainable Development Goals and the 2050 Vi sion for Biodiversity, the need has been emphasized for urgent and concerted efforts, such as the promotion of edu cation and knowledge generation and sharing, including scientific, indigenous and local knowledge about nature and its conservation and sustainable use (Díaz et al., 2019).

Biodiversity education

Since the adoption of the CBD, the need was recognized to promote and encourage understanding of the impor tance of biological diversity conserva tion through the media, and inclusion of this topic in educational programs. It becomes important to have an educa tion with biodiversity as a pedagogical goal, that is to say, biodiversity education (González Gaudiano, 2002). At a local level, Mendoza’s Provincial Education Law (2002) maintains that the education system should provide development of skills to preserve nature.

This paper studied some aspects of how biodiversity education is practiced in formal and non-formal settings in the province of Mendoza (Argentina). Our study was focused on two key practitioners of biodiversity education: prima ry school teachers and rangers. Rangers were included because they teach local biodiversity and conservation when they guide schools and people who visit pro tected areas. Teachers and rangers have to prepare their classes on biodiversity and can use different print and digital resources coming from different sources. We explored 1) type of resources (print, digital, and others) used by practitioners to prepare a lesson plan on biodiversity; 2) sources of materials available at the school and in protected areas (govern ment and non-government agencies, institutions, etc.); 3) teaching methods and resources used by teachers in a les son plan on biodiversity. We also asked key informants (teachers working on the training of primary school teachers and rangers) about resources used for biodiversity education.

Material and Method

We applied a combined methodological approach based on a quantitative mail survey and interviews with key infor mants. During 2017 and 2018, 106 pri mary school teachers (from a total of 870 in Mendoza) and 64 rangers (from 200 ones working in protected areas) an swered the survey through a form avail able on the Internet. In the first section of the survey, they entered personal and professional information.

In the second section, they were asked about the resources used to prepare a lesson plan on biodiversity (the options were: print resources-books, maga zines, brochures, pictures, and news papers-, digital resources-websites, videos-and other resources-consulting with specialists, teacher training materi als, and classes by other colleagues), the sources of resources available at schools and in protected areas (the categories were: government education agencies- National Ministry of Education, Pro vincial General School Agency-, aca demic institutions-National University of Cuyo, National Council of Scientific and Technological Research-, govern ment environmental agencies-National Secretariat of Environment, Agency of Renewable Natural Resources, Nation al Institute of Agricultural Technology, Institute of Health and Quality of Ag riculture of Mendoza, General Department of Irrigation-, non-government environmental organizations), and the activities and materials used to devel op the class on biodiversity. In order to know the teaching methods and resourc es used in the classroom, we particularly asked school teachers how often (once a week, once a month, once a year) they include: 1) activities involving analysis of texts, brochures, posters and maga zines, using print material, 2) activities related to analysis of educational and documentary videos, use of information and communications technology (ICT), classes by invited specialists using digital resources, 3) experiential learning activ ities such as making school trips (to visit protected areas, interpretation trails, zoo, museums, etc.), working with laboratory material, working with interviews and other social techniques, building school biological collections, participating in science fairs, etc. Particularly for rang ers, an open question of the survey asked them about the difficulties they encounter in pursuing biodiversity education in protected areas.

Data were analyzed using a sample test for equality of proportions in R version 3.6.1 (R Core Team, 2016).

In order to deepen the study on bio diversity education, five teachers who work at institutes for training primary school teachers were interviewed. They were asked about the materials and resources teachers count on for preparing their lesson plan on Mendoza’s biodi versity. The qualitative data from the interviews were analyzed by extracting common and heterogeneous meanings from the different opinions (Hernández Sampieri et al., 2010).

Results

Teachers who responded to our survey are between 25-45 years old, and they were 94% women. Currently, 72% of them are teaching in urban schools and the rest in rural schools. Almost 80% of them have a primary education teaching degree obtained in non-university teach er training institutes of Mendoza.

Rangers are between 25-45 years old, and 75% of them were men. They have been working in protected areas for 2 to 28 years, developing environmental edu cation activities directed to schools and general public visiting the reserves.

Type of resources on biodiversity used by practitioners to prepare a class lesson plan

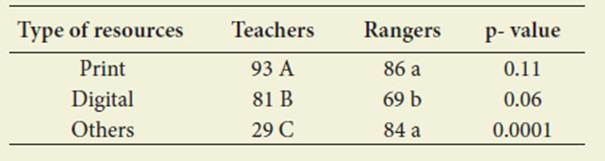

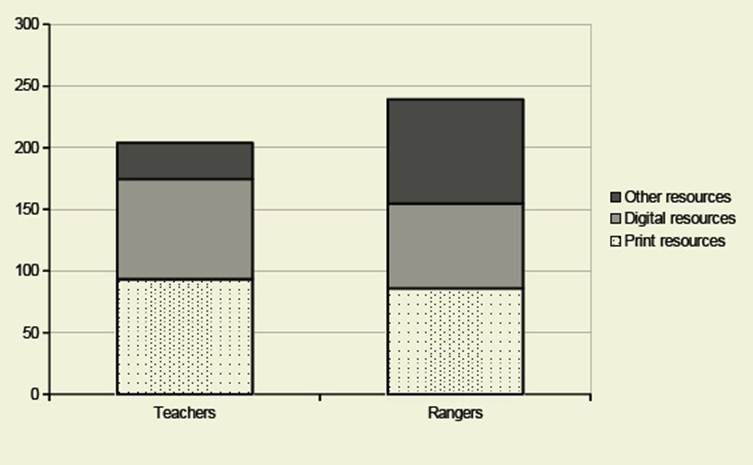

The teachers mentioned print resources more often than digital ones and, to a lesser extent, they named “other resourc es” (X-squared = 112.84, df = 2, p-value < 0.0001; Table 1; Figure 1).

Table 1: Percentages of responses about types of resources used by practitioners to plan a bio diversity class (several answers possible). Letters indicate significant differences among types of resources used by each actor; p-value indicates differences between teachers and rangers in the use of each type of resource. Source Authors 2017-2018. Tabla 1: Porcentajes de respuestas sobre los tipos de recursos utilizados por los educadores para planificar una clase sobre biodiversidad (varias respuestas son posibles). Las letras indican diferencias significativas entre los tipos de recursos utilizados por cada actor; el valor p indica diferencias entre los maestros y los guardaparques en el uso de cada tipo de recurso. Fuente Autores 2017-2018.

Figure 1: Percentages of responses about types of resources used by practitioners to plan a biodiversity class (several answers possible). Figura 1: Porcentajes de respuestas sobre los tipos de recursos utilizados por los educadores para planificar una clase sobre biodiversidad (varias respuestas son posibles).

Rangers mentioned that they use print and “other resources” more than digital resources to prepare a lesson plan on biodiversity (X-squared = 7.14, df = 2, p-value = 0.03; Table 1, Figure 1).

Comparisons between practitioners regarding the resources used yielded dif ferences only in the mention of the cate gory “other resources”, which was more often named by rangers (X-squared = 48.51, df = 1, p-value < 0.0001; Table 1, Figure 1). This category included mate rial obtained from training courses, con sulting with scientific researchers and technicians, and learning through interaction with local people.

Sources of print resources available at schools and in protected areas

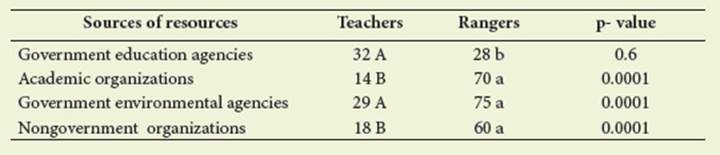

According to the teachers, resourc es available at schools were produced mainly by government education and environmental agencies, whereas a low er number came from academic insti tutions (research institutions, univer sity), and from environmental NGOs (X-squared = 13.32, df = 3, p-value = 0.004; Table 2).

Table 2: Percentages of responses about the sources of resources on biodiversity available at schools and in protected areas (several answers possible). Letters indicate significant differenc es among sources mentioned by each actor; p-value indicates differences between teachers and rangers in the mention of each source. Source Authors 2017-2018. Tabla 2: Porcentajes de respuestas acerca de las fuentes de recursos sobre biodiversidad disponibles en las escuelas y en las áreas protegidas (varias respuestas son posibles). Las letras indican diferencias significativas entre las fuentes mencionadas por cada actor; el valor p indica diferencias entre los maestros y los guardaparques en la mención de cada fuente. Fuente Autores 2017-2018

Rangers mentioned government environmental agencies, academic institutions, and private en vironmental organizations as the main sources of resources currently available in protected areas. They had less re sources produced by government educa tion agencies (X-squared = 35.12, df = 3, p-value < 0.0001, Table 2).

When the mentions of sources of re sources available at schools and in pro tected areas were compared between practitioners, rangers mentioned more government environmental agencies, organizations dedicated to scientific re search and knowledge production, and private environmental organizations than teachers did (Table 2).

Teaching methods and resources used in the classroom

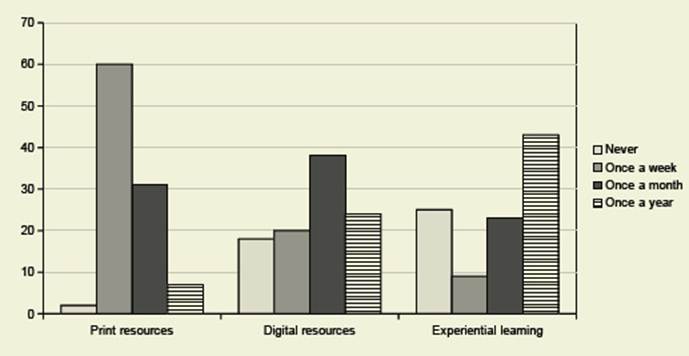

There was a significant difference in the frequency of use of different teach ing methods and resources in the class room. Teachers indicated that teaching methods involving activities with print resources are the ones most frequently used “once a week” (X-squared = 112.75, df = 3, p-value < 0.0001, Figure 2).

Figure 2: Percentage or responses about the frequency at which different teaching methods and resources are used in the classroom. Figura 2: Porcentaje de respuestas sobre la frecuencia con que se utilizan diferentes métodos y recursos de enseñanza en el aula.

These activities included analysis of printed information. Teaching methods involv ing activities with digital resources are the ones most frequently used “once a month” (X-squared = 13.01, df = 3, p-value = 0.005, Figure 2).

Experiential learning involving a di versity of resources is practiced “once a year” (X-squared = 31.15, df = 3, p-value < 0.0001, Figure 2). It includes, among other activities, school trips to protected areas, where students will come in con tact with rangers in their role as biodi versity educators.

Opinions of teachers working on the training of primary school teachers, and rangers

Teachers working on training primary school teachers highlighted the scar city of educational resources on Men doza’s biodiversity. They said that “for the specific study of biodiversity of Ar gentina and Mendoza, publications are fragmented” and continued explaining “except for a few examples, schools have no teaching materials for the topic of biodiversity, especially Mendoza’s biodi versity. It is the teachers themselves who usually produce these materials, at best; or they use examples of the diversity of other places”.

When asked about the difficulties they found in pursuing biodiversity educa tion, most of the rangers mentioned the lack of educational resources in the pro tected areas. One of them said “we lack materials, we lack institutional support, and above all we lack coordination with formal education institutions”. Other rangers mentioned “the need for training in didactic tools and the lack of support from the Agency of Renewable Natural Resources of Mendoza to develop educa tional activities”.

Discussion

Our study showed some aspects related to the practice of biodiversity education by primary school teachers and rangers in Mendoza. Both practitioners use a variety of resources to prepare a lesson plan for a biodiversity class, including printed, digital and “other resources”, such as material obtained from train ing courses, consulting with scientific researchers and technicians, and learn ing through interaction with local peo ple. The difference among practitioners was that rangers mentioned using few er digital resources and more of “other resources” than teachers. There are dif ferent sources of resources on biodiver sity available at schools and in protect ed areas. In schools, resources mainly come from government education and environmental agencies, whereas pro tected areas receive resources from aca demic institutions, and government and non-government environmental organi zations. Nevertheless, both practitioners pointed out the lack of educational re sources, such as books, posters, videos, etc. about local biodiversity. In the class room, learning about biodiversity is still limited to learning from textbooks and digital materials, whereas experiential activities such as visiting protected areas, museums, and interpretive trails are in frequently proposed by teachers. Activities outside the classroom enhance spon taneity, knowledge related to daily life and traditional knowledge that can then be adopted and deepened in the class room (Diaz Isenrath & Morant, 2017).

Teachers and rangers are two key prac titioners in biodiversity education. With different professional training, both have an understanding of nature and biodiversity. On the one hand, primary school teachers have knowledge of the conceptual barriers that students face in learning, and knowledge of strategies for working with students, but many of them have the belief that teaching biodiversity applying experiential methods based on nature requires a more special ist knowledge than what they have (Gay ford, 2000; Lindemann-Matthies, 2006). As a consequence, many teachers do not encourage students to experience nature first-hand and are teaching biodiversity mainly through print and digital media (Barker, 2002). On the other hand, rang ers have theoretical knowledge about biodiversity and conservation, and a wide practical knowledge about nature, but they recognize their lack of teaching tools (Slattery & Lugg, 2002).

During preparation of a lesson plan for a biodiversity class and application of teaching methods in the classroom, teachers rely on print and digital re sources, although print resources, such as textbooks, appear to be the most important resource. School textbooks provide a valid conception of the knowledge to be taught (Cobo Merino & Batanero, 2004). However, some problems have been described regarding textbooks’ treatment of dif ferent topics, such as the concept of biodiversity (Bermúdez et al., 2014), far from the new “people and nature” framework proposed by IPBES (Díaz et al., 2019). It could be expected that the resources produced by academ ic institutions would contain more up-to-date contents on biodiversity. It has been emphasized that scientif ic researchers need to be much more strongly proactive in their approach to communicating science, in formal and non-formal educational settings (Bick ford et al., 2012). When local scientists are not committed to engaging in the production of resources to assist edu cators, practitioners rely on tradition al resources, which show a strong bias toward exotic biodiversity and toward people and nature relationships taking place in other parts of the world, with far-reaching implications for biodiver sity education in a regional and local context (Campos, 2012; Campos et al., 2012, 2013; Celis-Diez et al., 2016).

The digital age has inevitably driven the transformation of a classic learning and teaching paradigm based on tradi tional resources into a new paradigm shaped by digital media technology (Cv etković & Stanojević, 2018). Information and communication technology allows building, testing, and critically evalu ating new knowledge, while promoting reflection on controversial ethical and social issues (Diaz Isenrath, 2015).

When rangers prepare the class on biodiversity, they have access to flora and fauna guides, scientific journals, technical reports, material from train ing courses, etc. coming from academic institutions, and from environmental organizations because of their close contact with scientific researchers and technicians working in protected areas. It is likely that rangers use less digital resources to plan a class because of the lack of internet connection in many pro tected areas, but they have the valuable opportunity to exchange knowledge with local people and learn about their relationships with nature.

When teaching methods in formal settings were explored, a “once-a-year” frequency was reported for projects in volving experiential learning, for exam ple building biological school collections, and participating in a science fair, which involves months of preparation. Teachers also organize a school trip once a year, as low a frequency as that record ed for schools around the world (Linde mann-Matthies, 2006). Several barriers were identified to a successful school trip, such as transportation, teacher’s training and experience, time issues such as school schedule, lack of school admin istrator support, curriculum inflexibility, poor student behavior and attitudes, and lack of venue options (Michie, 1998). However, students on school trips are motivated to develop connections be tween the theoretical concepts learned in the classroom and what they have experienced in nature (Falk & Dierking, 2000).

The roles in biodiversity education fulfilled by teachers and rangers, the two studied practitioners, converge in pro tected areas. This space should encour age them to communicate and develop a partnership in the sharing of teaching experiences in formal and informal set tings, with the aim to enrich biodiversity education.

uBio

uBio