Hayao Miyazaki speaks directly to Japanese women of all ages with specific reference to those who make the final transformation in their personal Heroines Journey’s by connecting to their spiritual awareness through nature. He creates what Maureen Murdock defines as “an authentic journey”: One that recognizes that women are more deeply connected to the mother earth and therefore make their spirit quests by practicing and experiencing empathy for others and by making a spiritual, often-magical connection to nature. From 1963 to present day, 77-year-old Hayao Miyazaki has been telling the Heroine’s Journey of strong girls or young women through his animated films, television series and manga. His films have consistently broken Japan’s record of the highest grossing box office and he won the Academy Award for his film Spirited Away in 2002, which is the only foreign film to have won the best animated film category. Many critics have chosen it as the best animated film ever made. Miyazaki says, "Many of my movies have strong female leads-brave, self-sufficient girls that don’t think twice about fighting for what they believe in with all their heart." They’ll need a friend, or a supporter, but never a savior. Any woman is just as capable of being a hero as any man (2013).

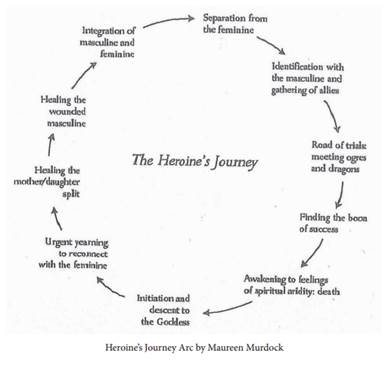

In 1985 Studio Ghibli was created and Miyazaki, along with three male partners and a team of mostly male animators wrote, directed and produced the highest grossing films in Japanese history relying on the coming of age journeys of his mostly female protagonists. As a male-dominated studio, they became known for creating the “Ghibli Girls” through their films about children as early as age five up to twenty-five and their psychological and spiritual journeys. It might seem unlikely that a group of men could create anything other than a Shero’s journey, defined as simply replacing the male hero with a female one who undertakes the same journey that a male would undergo -but this isn’t the case. Miyazaki’s masterpiece, Spirited Away or No Sen to Chihiro Kamikakushi is a story that reveals Miyazaki and his team can craft a story that follows more closely to what Mau-reen Murdock calls “The Heroine’s Journey” in her book, The Heroine’s Journey: Woman’s Quest for Wholeness (Shambala 1990). She outlines ten stages below.

Separation of the Feminine

The opening image in Spirited Away is a bouquet of delicate and feminine pink “Sweet Peas”, the flower of goodbye in Japanese culture. Ten-year-old Chihiro Ogino is in the back seat of her parents Audi A4 refusing the “call to adventure” as they speed down the highway towards their new home. She reads the card tucked into the flowers which says, “Good Luck Chihiro. Hope we meet again.” She doesn’t want to leave her life-long friends and schoolmates behind and the security of all that she’s known. She is disillusioned with what she expected her life would be. When you’re ten years old, you’re establishing your identity. It is the age for most girls of the first inkling of their sexuality. Chihiro’s character has been described as” whiney”, “pessimistic”, “sulky”, and “sullen”, but everything she has ever known, home, community, teachers, and friendships is being torn away from her by her parents’ move to the suburbs. Every aspect of her life is being threatened by this first journey to the unknown, this first threat to her “self” physically, sociologically, and psychologically. Will she make new friends, will she fit in, will she like her new home are the many questions running through her mind. Who will she become? And will she be forgotten? There is in this introduction to the “normal” world a longing for the past for Chihiro. She doesn’t dream of the new adventure that awaits her in a new town and a new community, but only of her friends … who might forget her. And then who would she be … a girl with no name.

Miyazaki says that in this story, “Words are power. In the world Chihiro wandered into, words have a great importance and immutability” (Director’s Statement on DVD). In a classic Joseph Campbell hero’s journey, Chihiro would set out on a quest to defeat evil but in Spirited Away no one is purely good or evil, and Chihiro learns through “perseverance to survive”. Spirited Away contains elements of both the Heroine’s Journey and the Hero’s Journey. The opening scene manages to accomplish both the “call to adventure” for Chihiro on her way to her new home, and that she’s in the middle of refusing it. Everything changes in an instant when the Audi A 4, driven by her Dad suddenly takes a wrong turn. Like most people who drive Audi’s, he thinks he can go anywhere with his four- wheel drive and based on personal experience, usually can. Their slogan is “Technology in Engineering”. This is a car that is marketed to upper middle-class men. Chihiro’s Dad is overweight, self- absorbed and based on his driving-a risk taker. He has moved his wife and daughter to a new home in the suburbs which neither one of them have even seen. Chihiro’s Mom remarks that it’s in the middle of nowhere and that she’ll have to shop in another town. He tells her they’ll just have to “make do”. When they pass the school and Dad points it out, Mom repeats her role as the person in the family dynamic who tries to make peace. She tells Chihiro it looks very nice just as earlier she reminded her that her Dad gave her a rose when Chihiro says her first bouquet is a goodbye. Chihiro is feeling betrayed by her father for moving them away and for having no choice in the matter. Her Mom is showing her through her behavior that it’s appropriate to accept and find the best in new situations, perhaps also the role she plays in her marriage as well. She’s establishing her feminine role that Chihiro will very soon choose to reject. The moment her father makes the wrong turn, the wrong choice for the family, Chihiro’s heroine’s journey has begun.

The patriarch of the family drives off the cement highway which suddenly stops and pauses to get his bearings. Once the Oginos continue down the stone path into the woods Miyazaki provides us with a visual history of Shinto from the car window. Chihiro’s understanding of Shinto is as murky as our own and for many Japanese today as well. She first sees a cluster of small stone shrines at the base of an ancient tree, clearly designated as being kami-filled by the offerings left in the little houses and the wood torii, two columns with a horizontal rail connecting them, which leans against the tree abandoned and which signals a transition to the sacred to all who pass under it. The patina of moss and age recall the “humble” origins of “rural Shinto ritual”. Miyazaki acknowledges this historical context saying:

My understanding of the history of Shinto is that many centuries ago they used ... the originators of Japan ... used Shinto to unify the country and that it then ended up inspiring many wars of aggression against our neighbors. So, there is still a great deal of ambiguity and contradiction within Japan about our relationship to Shinto, many wish to deny it, reject it. My feeling is that I have a very warm appreciation for the various, very humble rural Shinto rituals that continue to this day throughout rural Japan. Especially one ritual that takes place on the solstice when the villagers call forth all of the local Gods and invite them to bathe in their baths. (2002 Press Conference for the premier of Spirited Away)

Chihiro doesn’t know what they are, so her mother has to tell her they’re little shrines that people pray to. Miyazaki’s reference to ancient existential Shinto, what is commonly called “Folk Shinto”, shows us that the youth in Japan are no longer connected to their spiritual history. Chihiro isn’t sensitive or responsive to the kami presence so she isn’t prepared for the changes they’re going to bring to her life.

Traveling deeper into the woods they pass an ancient statue almost hidden by the leaves that Chihiro sees and instinctively knows is a symbol of power. Having statues mark the entrance of Shinto temples as guardians began when Buddhism began to assimilate into

Shinto traditions and it too is separated from the other half of its pair in the same way Shinto was later separated from Buddhism and Confucianism to “preserve” the cultural purity of the tradition. This is a visual reference to what came to be known as “Shrine Shinto”. Chihiro is being shown the history of the world she will encounter on her journey. Suddenly their car is halted by the missing half of the guardian pair, who now serves as a bollard to obstruct traffic and stop the Ogino family from going farther. The round stone statue is a called a Dōsojin, a two-faced smiling woman wishing Chihiro good luck on her journey into the kami world of spirits.

Her father jumps out of the car to investigate the large tunnel before them and Chihiro follows tossing her flowers into the back seat and ignoring her mother, who calls to her to come back. Chihiro ignores her and follows her Dad. This foreshadows the first rejection of the feminine for Chihiro. Those farewell flowers just moments ago so precious to her is Hanakotoba, the Japanese for of the language of flowers. They communicate and represent the love and farewell of her best friend with an impression of nature that conveys emotion to the recipient. It is a subtle feminine communication from her friend that will become a powerful reminder for Chihiro to remember her name. As Chihiro and her Dad stand at the mouth of a long tunnel, she clutches his arm in fear of him. Her father represents strength and safety to her, and his masculine role is one of logic, analysis and risk. As the air blows into the tunnel past her, feminine intuition nudges her again that this place is not what it appears to be, and she begs him not to. But Dad insists he wants to go investigate, and both Chihiro and her mother who has joined them sense this is a mistake. Her Dad tells her not be a “chicken”, questioning her moral courage and then tries to convince her that it’ll be fun. Chihiro runs back to the Dõsojin and refuses to go, and her Mom tells her to wait in the car and together her parents disappear into the darkness of the tunnel. She is alone with her fear and the statue, and she rejects her feminine intuition and runs after her mother, clinging to her.

Her journey through the tunnel is like her rebirth. When the family emerges into an empty train station, a nostalgic place with sun slanting thorough a stained-glass window and a fountain trickling water it is a place of transition, a place where journeys begin and end. Her parents ignore all of the visual clues around them that this is a sacred place that is worthy of respect for the kami, and Chihiro hangs tight to her mother until they emerge from the station into a lush meadow with nearly dry river bed. Her parents hurry away leaving Chihiro to scramble over the rocks on her own. She begs them to stop but they are intent on finding the source of the delicious food they smell. Chihiro relies on her feminine intuition to guide her to the choice she makes about not eating the sacred food they have stumbled upon which are offerings for the kami gods. Her parents are conditioned to see the food as something they can purchase harkening back to the Regan era of consumption and corporate greed. Her father and mother dive in and her father says not to worry he has credit cards and cash. Chihiro’s father, with his expensive car and a job that he puts ahead of his family, decides this place must be an abandoned amusement park that recalls the financial bubble that burst during the Reagan Era. Chihiro has been raised and taught that money can solve all problems. Money can excuse a lack of respect and satisfying personal needs regardless of others is acceptable if you have power and wealth. These are the masculine values that Chihiro is going to learn to reject on her journey. Chihiro rejects both her mother’s imploring her to try the tender and delicious food and her father’s assumption that as long as he can pay for it with money they can eat as much as they want. As her parent’s wolf down the food, Chihiro is disgusted by their greed. Her father even sounds like a pig as he shoves food into his face. Chihiro yells at them but they ignore her and continue to gorge themselves. She finally leaves them and walks out into the abandoned street of restaurants. She separates herself from the feminine by not eating the food despite their insistence, especially her mother’s entreaty to taste it.

Chihiro walks away from both of her parents, separating herself from their values and beliefs. This is a part of the journey that Murdock explains as the separation of the feminine when the daughter rejects the role she has assumed in her life. She is not going choose her mother’s role of supporting her father in every wrong decision he makes.

When Chihiro leaves her parents and walks to the bridge, she sees the train arriving from below her and her fist ally, Haku appears and warns her that she must cross the river before sun down or she will be trapped here. Chihiro runs back to find her parents only to discover that they have been bewitched and turned into pigs! Dark shadowlike figures begin to appear as the lamps are lit, the kami workers at the bath house whose job it is to cleanse the kami spirits who are beginning to arrive. Chihiro tries to cross the dry river bed but it has now become a huge river with a barge approaching filled with the kami spirits coming for their solstice cleanse.

Terrified Chihiro runs back towards the bath house and crouches in the darkness terrified and gradually disappearing until Haku finds her. He gives her a berry to eat and restores her solidity before she completely disappears. Without her parents to define her, Chihiro is nonexistent and insubstantial. And then a winged creature appears in the shape of a large bird with the face of a woman. This is the witch’s bird with the face Yubaba. Haku tells Chihiro that she must ask Kamaji who stokes the fires for the bath for a job. No matter what happens, if Chihiro works Yubaba can’t turn her into an animal and that it is also the only way to save her parents. And when he calls her Chihiro, she asks how he knows her “name” and he reminds her that she told him long ago.

Identification with the Masculine and Gathering Allies

Chihiro sets off to find Kamajiand to beg him for a job. She enters a world of physical labor that identifies with the masculine work ethic of slavery to the job. As Murdock explains, “Part of the Heroine’s quest is to find her work in the world which enables her to find her identity. It is important for a woman to know that she can survive without dependence on parents or others so that she can express her heart, mind and soul. Skills learned during this part of the heroic quest establish a woman’s competence in the world” (pg. 44). Chihiro makes her way to the bowels of the bath house and is introduced to the Susuwatari, the little soot sprites that feed the coal into the fire that heats the baths in exchange for some colorful Japanese candy. Chihiro makes friends with them by helping them to carry the coal and she learns that if they aren’t given a “job” to do they will turn back into soot. In addition to Haku, Chihiro meets another ally, Kamaji, a spidery old man with eight arms who mixes the herbal remedies and commands the boiler room. At last he agrees to send her on her journey to meet with Yubaba to ask for a job because she has demonstrated to him her ability to overcome her fear of speaking up for what she wants, her kindness to the soot sprites and her persistence in asking for a job. He also introduces her to another ally, Lin, who also works in the boiler room feeding the Suswartari. Kamaji introduces Chihiro as his granddaughter, protecting her and convinces Lin to take Chihiro up to sign a contract with Yubaba. He even bribes Lin with a roasted newt.

Trials on the Road

Chihiro must journey to Yubaba and convince her to give her a job if she has any hope of saving her parents and breaking the spell. She is going to face many trials that attempt to dissuade her from achieving this goal. Miyazaki tells us exactly what Chihiro must learn, “in everyday life, where we are surrounded, protected, and kept out of danger’s way, it is difficult to feel that we are working to survive in this world. Children can only enlarge their fragile egos.” Chihiro is going to have to learn “flexibility and patience, and decisive judgement and action.” Chihiro is confronted with situations which challenge her physically, socially and psychologically in addition to her understanding of reality. The kami world that Chihiro has entered of Shinto belief is not an easy world to understand. In his book Shinto: The Way Home (University of Hawai’i Press 2004) Thomas Kasulis describes it as a way of living in the world and experiencing those feelings of awe and mystery of the natural world. It’s both a feeling and a way of seeing the world. Inherent in the ancient tradition came the honoring of not only the natural phenomena that inspired awe around the rocks, trees, and mountains which contained kami spirits but also in those who came before them in a belief that ancestors are sacred and could eventually become kami them-selves. Kasulis explains:

I can cite four areas: the importance of connectedness to feeling whole; the appreciation of awe; the function of ritual praxis; and the lingering nostalgia for a bygone existential spirituality. First, it is hardly surprising to point out that spirituality has something to do with feeling connected. In many religions, this connectedness has a strongly transcendent dimension. That is: because of a connection to something behind, beyond, or at the base of the ordinary world, the spiritual person’s relation to this world-its people, its natural phenomena, its social fabric -may be transformed. (pg. 165)

Kasulis describes the psycho-spiritual journey that Chihiro must complete to find her way home. Her journey is not a story in which she grows up, but rather one in which she learns to connect to others and draw on something that is already inside of her. Haku reminds her that she has already met him, she already knows this Shinto spiritual world, she just has to remember it.

Chihiro’s meeting with Yubaba to ask for a job forces her to overcome her terror of the sorceress to save her parents. Yubaba is an old woman, with a grandmotherly bun, a large mole on her third eye and she’s suggestive of the “crone” stage of feminine myth. She’s also a demanding tyrant and who employs hundreds of bath house workers and cares only about money and her giant infant son named Boh. She cons her workers into signing contracts which allows them to work but they gradually forget their names and their identities and can’t leave. Miyazaki says, “To take a name away from a person is an attempt to keep them under perfect control … I am arguing in this film that words are our will, ourselves and our power” (Director’s Statement DVD). Our names might be handed down or given to us or bestowed after some elaborate naming ritual, but their documentation represents an individual to the government and legally they define our parents and usually our gender. Renaming someone takes away their identity. Chihiro must navigate this dangerous world where she can be swallowed alive with her name intact if she is ever going to escape this world.

Chihiro proves her loyalty to Haku, Kamaji and Lin by refusing to say who helped her and shows her persistence in asking for to work. Chihiro, or Sen as she will now be called when Yubaba steals her name, is doing exactly what Murdock tells us women do when they try to take on a masculine role in the workplace. Chihiro loses her identity and will toil as a worker slave to survive. The only way she will be able to free herself is by reclaiming her identity and remembering her name. She can only accomplish this by connecting to others and she and Haku’s friendship will allow them both to recall their identity and find freedom from Yubaba’s spell. Yubaba’s obsession with gold and material things, her apartment is rich and sumptuous, connects us to the masculine role of Sen’s father, now languishing his days away as a swine. He too believed that money and gold would solve his problems.

Meeting Ogres and Dragons

Before Sen begins her job Haku again takes her to a beautiful garden, connecting her to nature and to her feminine aspects. She visits her pig parents who have eaten so much they are “asleep” and no longer remember they are human. Haku gives Chihiro her clothes that have been taken from her and in them she finds the card from the opening scene that was tucked inside her flowers. She remembers her name is Chihiro and Haku tells her he has forgotten his true name. Chihiro renews her vow to save her parents.

Sen has opened the door and let in a strange spirit called No Face, because she felt sorry for him standing in the rain. No Face reflects back whatever people and energy he encounters. No Face as a character can represent all women who lose their own identity, the ability to articulate their own desires and needs and who simply absorb the energy of those who surround them. Because of Sen’s kindness No Face becomes obsessed with her and tries to give her whatever she wants so that he can ultimately consume her. But Chihiro refuses to take the many bath tokens he offers, she reflects only honesty, respect and kindness back to No Face and this is how Sen survives. Her ability to adapt to new situations is now reflected back to her from No Face and he disappears.

When the Stink Spirit arrives, Chihiro is given her ultimate trial and ordered by Yubaba to cleanse it. But this is no ordinary Stink Spirit but an ancient river spirit that Sen, with everyone’s help including Yubaba’s who gives her a rope and Sen ties around the handle-bars and together they work to remove a bicycle that has been stuck in the sludge. With a long line of everyone tugging the bicycle is freed and releases all of the discarded objects and filth the River Spirit has collected. Grateful for Sen’s bravery in rallying all of the workers to help release the bike, and now transformed into a dragon with an old man’s face, he gives her a small ball of dirt as a gift. Sen is learning that through ritual one can experience the Shinto expression of connectedness to community and the individual. This is the stage on her journey when she has her first boon of success.

Success at Last!

As the ancient River Spirit departs he leaves behind all of the gold that has fallen into the river behind. Everyone scrambles to get the gold and No Face watches the greed that the workers display as they scramble to get it all. No Face reflects their greed back to them and begins to cough out gold. Everyone celebrates Sen for her success in cleansing the river spirit and freeing him to return to where he belongs. This is Sen’s moment of triumph. Even Yubaba congratulates her because she made a lot of money. In a Hero or Shero’s journey this would be the end of the story. She has completed a number of trials and tests, getting a job with Yubaba, surviving No Face, encountering and serving kami spirits which are as diverse as giant radishes to strange creatures. She has revealed the Stink Monster was actually an ancient river spirit and helped him through her hard work to transform into a dragon. She has learned that river spirits transform into dragons and has received a magic dirt ball which may save her parents. But this isn’t the end of Sen’s Heroine’s Journey.

Heroine Awakens to the Knowledge of Death

After this success Sen saves Haku who has transformed into a dragon by opening a window and calling to him by name as he’s being attacked by Shikigami or paper spirits that look like small birds. Sen recognizes that this river dragon is Haku. But after resting with her for a moment, he flies up to Yubaba’s penthouse for safety and Sen follows to try and save him as he is bleeding to death from paper cuts. When she arrives one of the paper birds transforms into Yubaba’s identical twin sister Zeniba and tells Sen that it is she that is trying to kill Haku for stealing a golden seal from her under the orders of Yubaba. Haku has become the apprentice of Yubaba because he wanted to learn her magic and now he has forgotten who he is. Zeniba puts a spell on Yubaba’s large baby Boh and transforms him into a mouse. The “Yubird”, with Yubaba’s face is transformed into a fly. Sen protects them like small pets and just before Zeniba is going to kill Haku he gathers enough strength to create a trap door which sends them all plunging down to the boiler room.

Sen realizes that Haku is going to die from his injuries. This part of her journey is where she awakens to the knowledge of death and knows that none of her masculine strategies of hard work or that anything No Face could give her can save her parents or Haku. Success isn’t measured by wealth but by the connectedness one has to friends and family. She forces the dirt ball given to her by the River Guardian into Haku’s mouth and he vomits up the seal. The spell is broken and Haku returns to human form. All of these transformations are only the foreshadowing for the transformation that Sen is going to make. Once she has obtained the seal that belongs to Zeniba, the next part of her journey will be to return it to Zeniba. If Yubaba represents the masculine aspects of the crone mother, Zeniba represents the feminine and Sen knows it is urgent that she return the seal. She must find a way to reconnect to the feminine and heal the wound of her mother.

Because Haku is still gravely ill from the spell, Sen decides she is going to go to Zeniba to return the seal, apologize and ask her to save Haku. Before she leaves on her journey she’s confronted by Lin, who tells her Yubaba is hopping mad because Sen let in a No Face. She admits her mistake and takes responsibility for her actions. Before Sen can leave she must first complete one final obstacle that demonstrates that she can think from a new perspective. She must solve the problem of No Face. She bows down before him empty of desire, he offers her anything she wants but she tells him he can’t give her what she wants. She tells No Face she needs to go on a journey and No Face, who has transformed into a large glutinous mass with arms and legs, begins to purge all of the desires of those he consumed. Sen and Yubaba work together to get him out of the bath house. Sen’s purity of intention helps No Face to leave behind all of the greed he consumed and after he vomits up a couple of bath house workers alive and intact, Sen invites him on her journey to Zeniba.

Initiation and Descent to the Goddess

Sen’s journey to return the seal to Zeniba contains one of the most beautiful scenes in an animated film as a train arrives that runs on the water. This train has been a recurring image throughout the film that she has seen from her window of the bath house. When Sen finally steps onto the train she gives all of the tickets she got from Kamaji to the conductor with Boh, still a mouse and Yu-bird still a little fly and No Face accompanying her. As they ride the train in silence it is filled with ghosts from another time. This is a moment in the story where the characters sit in silence and stare out at the scenery. Miyazaki explained this in an interview with Roger Ebert.

We have a word for that in Japanese. It's called ma. Emptiness. It's there intentionally. [claps his hands] The time in between my clapping is ma. If you just have non-stop action with no breathing space at all, it's just busyness. but if you take a moment, then the tension building in the film can grow into a wider dimension. If you just have constant tension at 80 degrees all the time you just get numb…If you stay true to joy and astonishment and empathy you don't have to have violence and you don't have to have action. They'll follow you. This is our principle.

The nostalgic train ride of Sen and her friends is the beginning of the dark night of the soul for Sen. She has forgotten her name, Haku is dying, her parents are still pigs and her only hope is to travel to a mysterious place called Swamp Bottom, find Zeniba and beg her to help Haku and save him. No matter how successful she was in her job it didn’t save her parents or Haku.

Yearning to Reconnect to the Feminine

There is a yearning in Sen to reconnect to Zeniba, the feminine side of Yubaba. Zeniba tells Sen, “Yubaba and I are two halves of a whole, but we don’t get along.” It is a challenge for all girls and women to find the balance between their masculinity and their femininity. Zeniba projects feminine attributes of providing them with nourishment by preparing tea and sweets for them all and when Sen asks her to return Boh and YuBird she tells her the spell wore off and they could return anytime they wish, but they have become best friends and they choose to remain transformed. After Sen returns the seal to Zeniba as begs for help, Zeniba tells her that one of the rules here is that Sen will have to save her parents and Haku all by herself. Sen asks for a hint

and Zeniba tells her it’s easy, “Everything that happens stays inside you, even if you can’t remember it.” No Face, Boh and Yubird learn to spin thread and knit a hair band for Sen who accepts the gift of the feminine and pulls her hair back with it. Sen then experiences the most important part of her journey as she mourns and experiences the loss of Haku and her parents. This allows her to release her grief and sadness and then with a renewed determination, she decides she is going to go back to save Haku on her own. Zeniba tells her to wait just a bit.

Healing the Mother/Daughter Split

She is about to leave when Haku shows up at the door completely healed and in his dragon form. Zeniba forgives him and No Face is invited to stay with her and become her apprentice. Sen embraces her, reuniting with her own feminine nature and then she tells her, “My real name is Chihiro.” Chihiro has reclaimed her identity by remembering her name. She has learned to respect her feminine attributes of intuition, connection to her community and embraces Zeniba in the same way she embraces her own feminine qualities. Zeniba gives her the nurturing and healing gift of what Murdock calls, “grounding in the ordinary.” As a grandmother figure Zeniba guides her to understand that the role of women as the center of the home which has been devalued by society just as the earth and our planet have also been devalued can be reclaimed through a connection with other women and through nature. Reclaiming her name Chihiro is able to reclaim her feminine identity.

Heroine Heals the Wounded Masculine Within

Chihiro climbs onto Haku’s back as they fly back to the bath house and then Chihiro remembers that she once fell into a river when she was a child and met Haku and the name of the river was Kohaku river. She tells him his real name is Kohaku. Instantly, the spell is released and Haku transforms back into a boy and they fall to earth holding hands. He remembers this full name as a guardian river spirit and that Chihiro was chasing her lost shoe when she fell into him and he carried her to shallow water. As they fall to earth together, Chihiro experiences what Murdock calls “the sacred marriage” of both her ego and her self and remembers her true nature. She cries tears of joy and happiness at rejoining both of her natures.

Integrating the Masculine and the Feminine

When they return to the bath house, the giant baby Boh transforms back into his former infant self who is now able to walk. Haku and Boh remind Yubaba that she must keep her promise and let Chihiro and her parents go. But this is still a masculine world and Chihiro must answer the question as there are rules Yubaba must abide by in this world. Chihiro steps forward and calls out to Yubaba, “Granny, I’ll do as you ask.” She steps up confidently to the pig pen and Yubaba asks her to pick out her parents, and Chihiro says, “Granny, I can’t they aren’t here.” Yubaba asks if that is her final answer and Chihiro says yes. Instantly the contract is destroyed, and all of the bewitched pigs are transformed to their former selves and the spell is broken. Everyone celebrates. Yubaba frees Chihiro and Chihiro thanks her respectfully and runs off with Haku to find her parents. When they reach the end of the bridge the water is gone and Haku can go no further. He tells her he is quitting his apprenticeship now that he remembers his name and that he will also return home. He promises her that they will find each other again. As she runs towards the tunnel she hears her parents calling her and she reunites with them. They tell her she shouldn’t wander away and they must hurry as the moving van will be arriving soon. Her parents don’t remember anything about being turned into pigs. But when they return to the car, it’s covered with leaves and dust and Chihiro is still wearing her hair band. As they back out of the forest and drive away the kami world recedes, but it will not be forgotten by Chihiro. Miyazaki has created a Heroine’s adventure for ten-year- old girls without weapons or battles or violence. He says, “In these days, words are thought to be light and unimportant like bubbles, and no more than the reflection of a vacuous reality. It is still true that words can be powerful. The fact is, however, that powerless words are proliferating unnecessarily” (Director’s Statement DVD). In this dangerous world, Chihiro learns the power that words can have to imprison her and that community, friendship, empathy, and connecting to the sacred Shinto world of the kami will be the tools she will need to live in this world without being swallowed up. Her Heroine’s Journey has shown her how to access what Murdock calls the “sacred feminine” by being reminded of her Shinto origins, the necessity of living mindfully, and respecting and protecting the garden of the spirit.