Introduction

Apis mellifera L. collects pollen from different flowers for brood rearing. During collecting trips, they pack floral pollen grains into pollen pellets (pollen loads), mixing them with nectar and saliva. These pollen loads are called bee pollen (BP) (48). Its composition strongly depends on plant species, geographic origin, and factors such as climatic conditions, soil type, and beekeeping activities (16). Crane (1990) states that BP production is the second most important bee product. Nowadays, tons of pollen, either processed or unprocessed, are sold for human and animal consumption (11).

Beekeepers collect BP from hives using special pollen traps and transport it to the processing unit (41). Generally, processing involves cleaning, freezing, thawing, dehydration, packaging, transportation, and marketing. The dehydration process aims to increase product’s shelf life. In nature, BP contains 20-30 g x 100 g-1 of water (moisture) and has a water activity ranging from 0.66 to 0.82, providing a favorable matrix for the proliferation of microorganisms and possible chemical and enzymatic reactions (40). In addition, if a long period elapses between pollen collection and consumption as a food supplement, mycotoxins produced by toxicogenic fungi could be produced (33). Consequently, microbiological contamination is one of the most important criteria to determine BP quality intended for human consumption.

BP is consumed as a dietary supplement, and its quality parameters are regulated by the Argentine Food Code (AFCode) under article 785. According to this code, the máximum molds and yeasts level allowed for trading purposes is 100 colony-forming units (CFU) g-1 of BP and 150 x 103 CFU g-1 for non-pathogenic aerobic microorganisms. Nevertheless, the legislation does not allow the presence of aerobic pathogenic microorganisms without specification of genera or species. Legislated quality standards and limits for BP do not exist in the European Union or internationally. For example, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not consider BP an additive. As previously mentioned, only a few countries, such as Brazil, Poland, Switzerland, Bulgaria, China, and Argentina, have established criteria for BP for human consumption (35). To our knowledge, there are few publications on the microbiological characteristics of BP ready to be sold in the retail market (5, 12, 14, 40, 48), and only two studies are from Argentina (9, 34).

Accordingly, we previously investigated the microbiological and chemical characterization of 36 BP samples of beekeepers from the Southwest of Buenos Aires Province, Argentina, at four sampling stage points of the production process (27). We also studied the traceability of potential enterotoxic Bacillus cereus strains, showing that BP could be contaminated at any point, emphasizing the importance of hygienic processing to avoid spore contamination (37). Moreover, we identified the aerobic spore-forming species in the microbiota of fresh BP samples intended for human consumption obtained in the main producing areas of Argentina (4). On the other hand, we evaluated whether properly processed BP could be conserved for more than 12 months without showing alterations in its microbiological and chemical qualities (26). Hence, the present investigation aims to characterize 10 commercial dehydrated BP samples from five different Argentine provinces, providing information on hygienic quality and health safety of what we consume. Therefore, we assessed microbiological quality, including potential mycotoxins while determining sample botanical origin and moisture.

Materials and methods

Bee pollen samples

Ten BP samples from five different provinces of Argentina were included in this study. All samples were purchased directly from supermarkets between April and May 2022 and were identified by progressive numbers from 1 to 10. All were sold as dried bulk products and stored at 4°C until testing. The gravimetric method was used for moisture determination (23). Briefly, two grams of each BP sample were dried in an oven at 60 ± 2°C, up to constant weight. Results were expressed in g %.

Microbiological characterization

Counts of filamentous fungi (FF), yeasts (Y), and culturable heterotrophic mesophilic bacteria (CHMB) were evaluated as previously described (25). Ten grams of each BP simple were homogenized into 90 ml of peptone water (Britania®, Argentina) (initial suspension). Decimal serial dilutions were performed using sterile distilled water. After incubation, the number of FF and Y was determined by counting in a range of 10 to 100 and 15 to 300 for CHMB. Enterobacteriaceae (ENT) were counted on Violet Red Bile Glucose Agar (VRBGA, Britania®) at 32°C for 24-48 h. Microbial counts were carried out in triplicate, and results were expressed as log10 colony-forming units g-1 (log10 CFU g-1).

Complementary microbiological determination

Aerobic spore-forming bacteria belonging to the Bacillus cereus sensu lato group were assessed as described by Alippi et al. (2022). The number of colonies was averaged, and the total colony-forming units (CFUs) were calculated per g of BP (CFU g-1).

Isolation and identification of Bacillus species within the Cereus clade (30) were made according to previously published methods (36, 37). After the heat-treatment step, 100 μl of the sediment-fluid mixture was poured in triplicate over the surface of polymyxin-pyruvate-egg-yolk-mannitol-agar (PEMBA) plates (Britania®, Argentina). Plates were incubated at 37°C and examined for bacterial growth daily and for up to 5 days (37). Presumptive colonies of B. cereus, i.e., turquoise blue crenated colonies (mannitol negative) surrounded by opaque zones of egg-yolk precipitation (lecithinase positive), were counted and re-streaked in Bacillus Chromoselect agar (Sigma-Aldrich®). Typical colonies were selected, i.e., blue with dark blue centers, showing a pinkish-beige pigmentation of the medium (3); colors of colonies and substrate were compared with a Pantone international chart and identified with a PMS number (http://www.cal-print.com/InkColorChart.htm) (2). Presumptive B. cereus isolates were tested as described by López & Alippi (2007).

Mycotoxin analysis

Aflatoxins B1, B2, G1, G2, fumonisins B1 and B2, ochratoxin A, and deoxynivalenol (DON) content of BP were analyzed using UHPLC-MSMS (8). One gram of each sample was weighed into a 15 ml plastic tube, and 2 ml of methanol was added. The mixture was shaken for 2 min and then centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was filtered into a vial through a 0.45 μm syringe filter and run with LC-MS/MS. The chromatographic conditions were the following: run time, 10 min; injection volume, 50 μL, column ACQUITY UPLCr BEH C18 1.7 μm, flow: 0.300ml/min and the mobile phase C: 500 grams of water, 20.8 grams of methanol (UPLC), 400 μL of formic acid and 335 μL of ammonia (30%). Detection limits (LD) obtained with this technique were: aflatoxins B1, B2, G1, G2 0.1 μg.kg-1; ochratoxin A 0.1 μg.kg-1; fumonisins B1, B2 0.1 μg.kg-1, and DON 0.1 μg.kg-1.

Botanical origin

The palynological identification of BP was performed with the method described by Armaza (2013) in samples from the provinces of Buenos Aires and Chubut. Briefly, a simple of 4 g, corresponding to approximately 300 pollen pellets, was considered representative of botanical origin. Pollen loads were analyzed under a stereoscopic microscope and sorted by color, shape, and texture, assuming each pellet was a homogeneous mass of pollen from a single plant (45). To perform the microscopic observations, pollen grains from pellets were mounted on slides using the technique proposed by Wodehouse (1935). When this technique was not adequate to determine pollen grain structure, the microacetolysis method (46) was used. Thus, the botanical origin of some samples was described onlywith the Wodehouse technique, and other samples required both. The pollen grains were identified by comparison with the existing pollen collection at the Departamento de Agronomía (Universidad Nacional del Sur, Buenos Aires, Argentina). Therefore, only six out of ten samples were analyzed. Those samples corresponding to its area of influence (from Buenos Aires to the south of the country) were analyzed. Pollen types were identified up to a species level or genus and up to tribe or family level when the morphology of pollen grains allowed no distinction. Each identified pollen load was weighed, and results were expressed as a percentage of total weight (43). The percentages assigned to each pollen type were expressed as predominant pollen (>45%), secondary pollen (45-16%), minor pollen (15-3%), and traces of minor pollen (<3%) using pollen frequency classes by Louveaux

(1978).

Statistical analysis

Data from FF, Y, and CHMB counts in the 10 BP samples were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance using InfoStat software (21). When a significant F-value was detected, means were compared with the LSD test (p<0.05).

Results and discussion

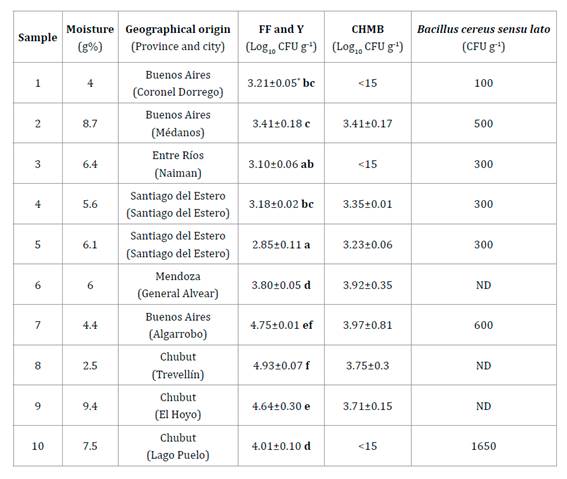

Microbial enumeration of FF, Y, CHMB, ENT, and moisture were performed to ensure that all samples collected were hygienically processed and conformed to the current microbial criteria set in the AFCode (Table 1, page 24). Moisture is among the most relevant factors affecting BP microbiological quality and conservation (6).

Table 1 Microbiological determination in 10 bee pollen samples obtained directly from supermarkets in five different Argentine provinces. Tabla 1. Determinaciones microbiológicas en 10 muestras de polen apícola obtenidas de supermercados de cinco provincias de Argentina.

FF and Y: filamentous fungi (FF) and yeast (Y); CHMB: culturable heterotrophic mesophilic bacteria; ND: undetected, 0 colonies. *Results are the mean of three replicates and ± its standard deviation. Letters in bold represent that bee pollen samples were different by LSD test with a significance of p = 0.05.

FF-Y: hongos filamentosos y levaduras; CHMB: recuento de bacterias aerobias mesófilas; ND: no detectable, sin colonias. *Los resultados se expresan como la media de tres réplicas y ± su desviación estándar. En negrita, las letras representan que las muestras fueron diferentes con el test de LSD, con un nivel de significancia de p = 0,05.

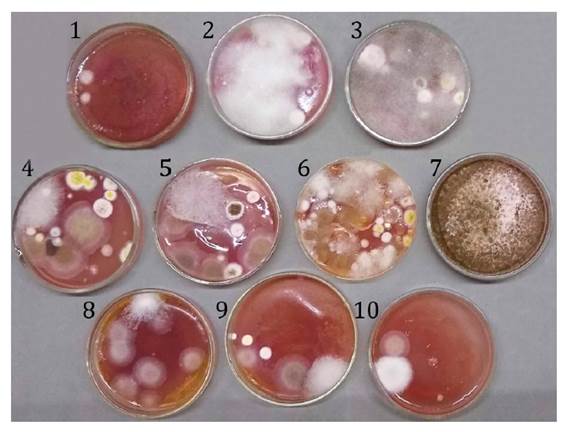

The safe humidity level was lower than 8% (AFCode), while the moisture of the studied dried BP samples varied between 4 and 9.4%. Only two samples had more humidity than allowed and showed higher FF and Y. Concerning CHMB populations, seven out of ten samples revealed microorganisms counts ranging from 3.23 log CFU g-1 (1.725 CFU g-1 BP) to 3.97 log CFU g-1 (18.750 CFU g-1 BP). There were no statistical differences between them, all showing lower CHMB than that allowed by the AFCode (150 x 103 CFU or 5.17 log g-1 of BP for non-pathogenic aerobic microorganisms). In contrast, all samples showed FF and Y counts higher than those approved by the AFCode (100 CFU or 2 log g-1 of BP). Counts for FF and Y ranged from 2.85 log CFU g-1 (725 CFU g-1 BP) to 4.93 log CFU g-1 (85.750 CFU g-1 BP). Several studies on BP from different regions of the world exceeded? the limit of FF and Y established in the AFCode (11, 12, 24, 32, 40, 47, 51). In this sense, our group in 2020 suggested the AFCode to modify this number to 5 x104 CFU per g of BP, as proposed by Campos et al. (2008). This modification is being treated (19). Enterobacteriaceae colonies were not detected in any of the BP samples studied. However, some fungal species developed after incubation at 37°C for 24 h on Petri dishes containing VRBGA. As shown in Figure 1 (page 24), these fungi grew in the plates with the selective medium used to search for enterobacteria in all samples. Fernández et al. (2020, 2021) also observed the growth of fungi in those media when studying BP samples from Argentina.

Figure 1 Filamentous fungi observed in the selective culture medium Violet Red Bile Glucose Agar when looking for enterobacteria at 37°C after one day of incubation. Figura 1. Hongos filamentosos observados en medio selectivo Agar Violeta Rojo Bilis Glucosa para conteo de enterobacterias a 37°C luego de un día de incubación

These observations may be explained by the fact that some filamentous fungi can biodegrade different dyes, such as those in VRBGA medium, i.e., neutral red and crystal violet (1, 15, 31). Species belonging to the Cereus clade were detected in seven out of ten samples, ranging between 100 CFU g-1 and 1.650 CFU g-1 of BP (Table 1, page 24). These values complied with the food safety criteria for B. cereus (<105 CFU g-1) (22). Colony counts revealed no statistically significant differences among the means of the samples.

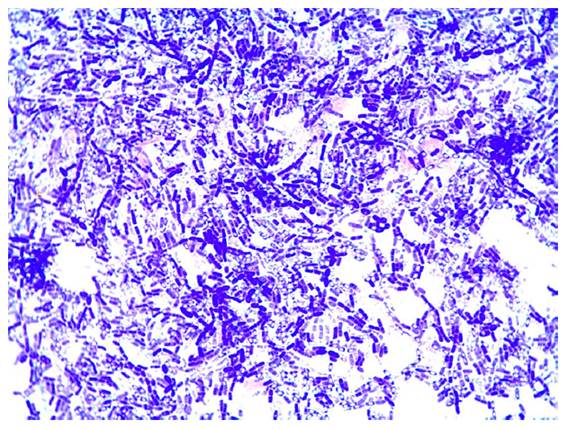

We identified 13 isolates of presumptive B. cereus according to colony morphology in selective and differential media. All isolates were Gram-positive and catalase-positive. Stained microscopic preparations showed ellipsoidal spores in a central position, not distending the sporangia, and the cytoplasm was filled with unstained globules (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Gram-stained microscopic preparation of B. cereus isolate (7.2) from simple number 7 of Buenos Aires province, showing ellipsoidal spores in a central position, not distending the sporangia, and cytoplasm filled with unstained globules. Figura 2. Tinción de Gram de un aislamiento de B. cereus de una muestra de la provincia de Buenos Aires, donde se observan esporas elipsoidales en posición central, sin distensión de esporangios y citoplasma con glóbulos sin teñir

Similarly, 12 isolates exhibited hemolytic activity of β hemolysis, and one (isolate 7.2) showed a discontinuous hemolytic pattern in sheep blood agar plates (10), probably due to the production of hemolysin BL. In PEMBA plates, isolates produced crenated colonies retaining the turquoise blue of the pH indicator because of their inability to ferment mannitol, acidifying the medium and generating an egg-yolk precipitation halo as a result of lecithinase activity. Moreover, when growing on Bacillus Chromoselect agar, 12 isolates showed large blue colonies [PMS 2746] with dark blue centers and pinkish beige color [PMS 152] of the medium, and only isolate 8.4 exhibited green colonies [PMS 361] with yellow color [PMS 114] of the basal medium.

The presence of B. cereus in Argentine pollen samples has been previously reported (4, 27, 37). Results obtained here were similar to those regarding spore counting that complied with the food safety criteria for B. cereus (< 105 CFU g-1) (22, 39). Concerning mycotoxins, none of the fumonisins nor DON was detected in the BP samples analyzed. Only aflatoxin B2 was detected in one sample, number 10, out of 10 (10%) in a concentration of 0.2 μg.kg-1 and ochratoxin A in two samples, 2 and 7, both in a concentration of 0.3 μg.kg-1. Aflatoxin B1 is among the hazardous toxic substances produced by Aspergillus (2017). Nevertheless, these mycotoxin levels were far from the limits allowed in humans (10 μg.kg-1) by regulations for other foods. Research on the presence of mycotoxins in BP, in general, is particularly scarce. Medina et al. (2004) stated that BP could constitute a significant risk factor in the diet of consumers by the presence of ochratoxin Shepard et al. (2013) described zearalenone as the main mycotoxin in BP. Cirigliano et al. (2014) studied in vitro mycotoxins produced by two species of fungi isolated from BP. None of the previous works analyzed the presence of mycotoxins in BP samples for human consumption. García Villanova et al. (2004) examined 20 commercial BP samples from Spain for aflatoxins B1, B2, G1, G2, and ochratoxin A. None showed quantifiable values of the aforementioned mycotoxins. Carrera et al. (2023) studied five mycotoxins (aflatoxin B1, ochratoxin A, zearalenone, deoxynivalenol, and toxin T2) in 80 BP samples from diverse climatic areas, organic and conventional beekeeping, with different floral composition and commercial format (fresh, dry, or bee bread). According to these studies, the most widespread mycotoxins in BP were aflatoxin B1, DON, ZEN, OTA, and T-2. In 28 % of the cases analyzed, deoxynivalenol exceeded safe limits, while aflatoxin B1, due to its generally high concentration, caused major public health concern in 84 % of the cases. It is important to note that legislation of the European Union establishes regulations on mycotoxins for a variety of foods, but almost no regulation has been issued on these metabolites in BP.

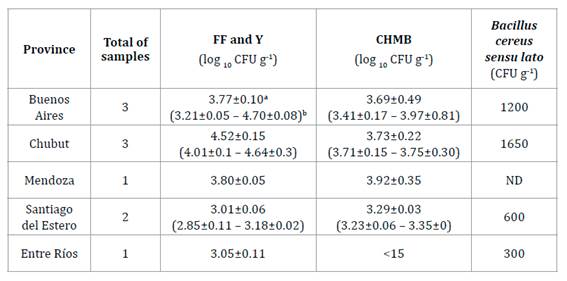

Variation in microbiological quality was found among samples from the same province (Table 1, page 24; Table 2). All samples from Chubut province exhibited higher counts of FF and Y than the rest of the samples studied (Table 2).

Table 2 Counting the range of microorganisms in dehydrated bee pollen samples according to each Argentine province. Tabla 2. Conteo de microorganismos en muestras de polen apícola deshidratado según cada provincia.

Mean value ± standard deviation; b Minimum - maximum value ± standard deviation.

a Media ± desviación estándar; b Valores mínimos - máximos ± desviación estándar.

Regarding CHMB, all BP samples showed similar counts, independently of their geographical origin. It is known that each piary has different collection and processing practices. Thus, the variation in the counts of microorganisms observed, even between samples from the same province, is aceptable considering apiary manipulation. On the other hand, the microbiological quality of all samples complied with article 785 from the AFCode, except for FF and Y. Therefore, if pollen is intended for human consumption, appropriate hygiene standards must be applied in all BP production operations. Proper BP handling and sanitation practices would improve microbiological quality (27, 49).

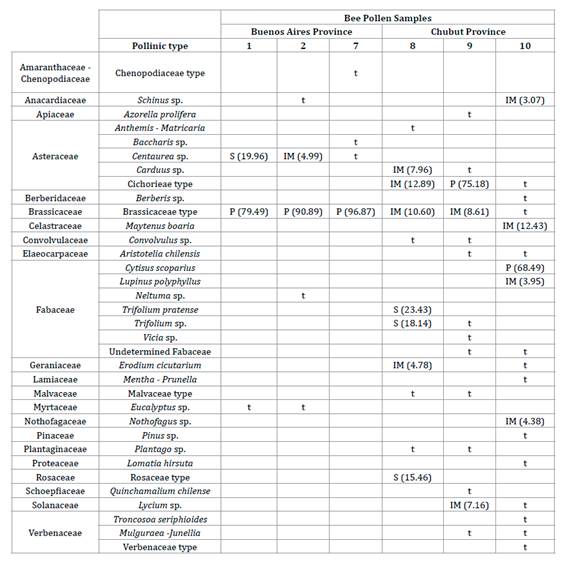

Regarding botanical origin, all BP samples analyzed were pollen mixtures, verified by identifying numerous botanical species (Table 3, page 27).

Table 3 Botanical composition of bee pollen samples from Buenos Aires and Chubut provinces. Tabla 3. Composición botánica de las muestras de polen apícola de Buenos Aires y Chubut.

P= predominant pollen (> 45%); S= secondary pollen (16-45 %); IM= minor pollen (3-15 %); t= traces or minor pollen (< 3%).

P= polen dominante (> 45%); S= polen secundario (16-45 %); IM= menor importancia (3-15 %); t= trazas (< 3%).

However, according to Louveaux’s classification (38), most samples were monofloral. Only the Trevelín sample from Chubut province was multifloral. The determination of monoflorality is significant since it could increase the economic value of the product, and it seems to be correlated to the abundance of bioactive compounds, such as polyphenols and flavonoids (44). Nevertheless, unlike honey, no regulation in our AFCode specifies the botanical origin of BP.

The Brassicaceae type (Figure 3, page 28) was dominant in BP samples from Buenos Aires province (Table 3), with Diplotaxis tenuifolia (“flor amarilla”) showing a strong presence.

Figure 3 Brassicaceae type which was dominant in bee pollen samples from Buenos Aires province. Figura 3. Tipo Brassicaceae fue dominante en las muestras de polen apícola de la provincia de Buenos Aires

This species, which belongs to a stenopalynous family, is of central importance in the contribution of nectar and pollen to the semiarid region of this province (52). On the other hand, BP samples from Chubut province showed the greatest floral diversity. El Hoyo (sample 9) showed the predominant Cichorieae type (Figure 4, page 28), whereas Lago Puelo displayed Cytisus scoparius (Figure 5, page 28).

Figure 4 Cichorieae type which was dominant in bee pollen samples from El Hoyo, simple 9 from Chubut province. Figura 4. Tipo Cichorieae fue dominante en la muestra 9 de El Hoyo perteneciente a la provincia de Chubut

Figure 5 Cytisus scoparius, dominant in bee pollen samples from El Hoyo, sample 9 from Chubut province. Figura 5. Cytisus scoparius fue dominante en la muestra 9 de El Hoyo perteneciente a la provincia de Chubut

All samples from Chubut province presented species of typical trees and shrubs of southern Argentina, which are geographical markers of pollen from that region (28), such as Maytenus boaria (“maitén”), Nothofagus sp. (“lenga”), and Azorella prolifera (“neneo”).

Conclusions

All the samples studied in this work, no matter the province nor the botanical origin, complied with the AFCode, except FF and Y. These results gave us more scientific support to make changes in our legislation, as we are doing, and to underline the importance of hygienic processing of BP to avoid microbial contamination. Further research should focus on two aspects not regulated in our AFCode nor in the legislation of the European Union: the presence/absence and quantity of mycotoxins and the importance of evaluating botanical origin. Both subjects will broaden our knowledge and legislation in terms of BP to know what we are consuming.