Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista argentina de cirugía

versión On-line ISSN 2250-639X

Rev. argent. cir. vol.113 no.1 Cap. Fed. abr. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.25132/raac.v113.n1.1511.ei

Articles

Young surgeons entering the workforce in the City of Buenos Aires. Need for restructuring of the general surgery training system

1 Sanatorio Municipal Dr. Julio Méndez. Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Introduction

Training in surgery has remained relatively uniform since the residency programs were introduced at the beginning of the 20th century1. Forty years later, Dr. Tiburcio Padilla created the first residency program in Argentina in 1944. In 1960 the system became consolidated and the Secretary of State for Public Health defined the medical residency program as “a system of professional education for graduates from medical schools with full-time education in service, during a determined period of time, with the goal of training for the integral, scientific, technical and social practice of a specialty”2. In Argentina, the residency in general surgery comprises a program of no less than 4 years, which should ensure training in the following areas: abdominal surgery including the abdominal wall, skin and soft tissues, prevalent diseases of the head and neck, peripheral venous system, thorax (excluding cardiovascular surgery) and basic peripheral artery surgery; ultrasound applied to surgery; image-guided percutaneous procedures; initial care of trauma patients, critically-ill patients in the emergency setting and in the intensive care unit; basic training in scientific method and biostatistics; training in medical ethics, communication, interpersonal relations and teamwork. It is advisable that the program also includes basic training in therapeutic and diagnostic endoscopic procedures. Residency programs in rural areas should emphasize training in the most prevalent conditions of the related surgical specialties3.

The continuous advances in science, along with the permanent expansion of the therapeutic tools and the extensive knowledge gained, have led to the progressive super-specialization of surgeons. According to several studies, between 70 and 80% of all the residents in general surgery continue their training with a second subspecialty or fellowship4, producing an imbalance between subspecialists and general surgeons. Several countries have expressed their concern about this issue. In the United States, the American Surgical Association (ASA) in partnership with the American College of Surgeons (ACS), the American Board of Surgery (ABS), and the Resident Review Committee for Surgery (RRC-S), established a Blue Ribbon Committee on Surgical Education in 2002, in an attempt to restructure the traditional system of the residency program. Among the recommendations published in 2004, the Committee stated that: “There is need to maximize efficiencies and minimize the duration of residency (...) the illusion that a uniform training program purporting to produce competence in all areas is fading (...) A new paradigm is needed that promotes both the varieties of general surgical practice and the subspecialties that derive from general surgery.”5

Many studies have been conducted to address the massive migration of specialists to a subspecialty. According to Coleman et al.4, 38% of general surgeon graduate trainees felt uncertain about their ability to develop as attending surgeons. In coincidence, the directors of training programs in surgical subspecialties concluded that trainees were not adequately prepared for the independent practice of general surgery. In a survey conducted by Mattar et al.6 among program directors, almost 50% of the respondents answered that new fellows were unable to operate for 30 unsupervised minutes of a major procedure, one-third felt that they could not adequately identify tissues and could not independently perform a laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and over 50% considered they were not proficient in laparoscopic suturing.

The aim of this study was to identify the proportion of general surgeons (GS) who dedicate hours of their practice in another medical specialty or move away from practice, and to analyze how surgeons enter the workforce at the end of the residency program.

Material and methods

1. A survey was submitted via e-mail, social media and instant messaging apps (Whatsapp) between January and April 2019 to:

A. Physicians who sat for the examination for the re sidency program in general surgery of the City of Buenos Aires between 2000 and 2018.

B. General surgeon graduate trainees from residen cy programs accredited by Asociación Argentina de Cirugía in the City of Buenos Aires, even if they were not certified by the association.

The survey consisted of 4 modules: 1) survey respondent’s personal data, 2) positions allocated in the different stages, 3) possible postresidency trai ning and 4) respondent’s job.

2. Data recorded by the General Directorate of Tea ching and Research of the City of Buenos Aires were reviewed.

3. Records of the competitive selection process, aca demic activity, job profiles and other public resou rces of professionals available online were also re viewed.

Data were stored using a Microsoft Office Ex cel2010® spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation).

Results

A total of 435 surveys were responded (response rate 32%), by 58 residents (13.3%), 320 general surgeons (73.6%), and 57 professionals who did not complete the specialty (13.1%).

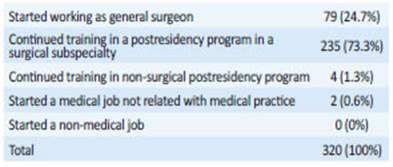

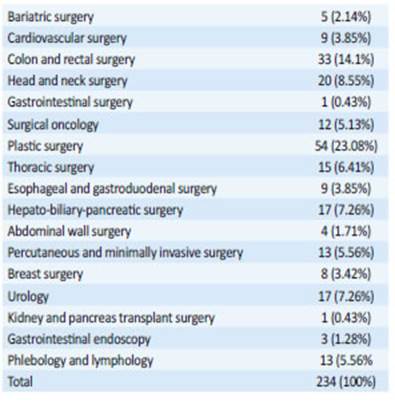

After completing the residency program, and in line with the results reported by other countries, 73.1% of the general surgeon graduate trainees continued their training in a postresidency program in a surgical subspecialty (Table 1). Plastic surgery (23.1%) and colon and rectal surgery (14.1%) were the subspecialties most chosen (Table 2). Only 24.7% immediately started working in general surgery.

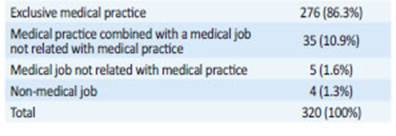

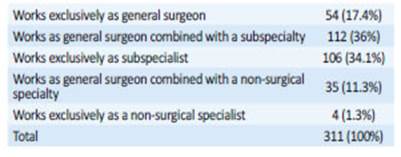

Among the 311 general surgeon graduate trainees with a job related with medical practice, 17.4% were exclusively dedicated to general surgery, while 34.1% were working only in their subspecialty (34% of them answered that they were still receiving training in the subspecialty) (Table 4). In addition, 44% of the general surgeon graduate trainees (13.8%) reported medical jobs not related with medical practice, and 20% of them were exclusively involved this activity (Table 3). Among this group, when we analyze the percentage of professionals according to their specialty, there is a non-negligible difference in the percentage of those who are exclusively dedicated to medical practice (78% of general surgeons versus 89% of subspecialists).

We analyzed what happened to the applicants for general surgery ranked in the first 100 positions in order of merit of the competitive selection process in the City of Buenos Aires by year from 2008 to 2018. Only 21% of them worked as general surgeons, while 67% practiced as professionals in one of the different surgical subspecialties and 12% were working in non-surgical specialties.

Discussion

After many years of successful training of professionals using the classic 4-year program, it seems appropriate to think about a progressive restructuring of our system to adapt it to the current state of science. The lack of confidence to perform procedures independently4 and the need for completing the 4-year residency program in general surgery to start training in the professional field of interest, appear as two issues to be solved with the new generations.

As opposed to the decrease in the demand for vacancies for general surgery in other countries, the number of applicants in the City of Buenos Aires has remained stable over the last 7 years, at around 5%.

One of the projects to address this issue, the Early Specialization Program (ESP), was designed and implemented by the ACS. The program allows dual training in general surgery and the respective subspecialty (vascular or thoracic surgery as pilot programs) and certification in 1 less year compared with the traditional pathways7. In a survey conducted by Coleman et al.4 in 2012, 63% of the survey respondents considered that this system should be extended to other subspecialties and, furthermore, 70% responded that a 3-year basic training track and a 3-year specialization track were optimal lengths of time to be devoted to each component. In 2011 the ABS approved flexible rotations for general surgery residency training, referred to as FIST (Flexibility in Surgery Training) and allowed residents to customize up to 12 of the final 24 months of residency for early tracking into one subspecialty track. It has already been developed in 9 institutions, with positive evaluations of the model by the participants in the flexible tracks, non-participants and program directors. Residents showed autonomy at work, increased exposure to complex operative procedures and greater interest in this modality8. In 2014, the ACS launched the Transition to Practice (TTP) program, with 30 accredited centers in the United States nowadays. The program consists of a sixth year of training in general surgery in a model similar to a fellowship, which allows new graduates to continue their training under the mentoring by senior surgeons9.

The duration of the residency programs varies worldwide. Brazil has the shortest program in Latin America, with a duration of 2 years until certification10, similar to the one in Russia11. Interestingly, many countries do not have a standardized program format or duration, and leave the final decision to the training institution, as Colombia and Japan12,13. Canada and the United States keep their traditional 5-year program, although the model and duration of the programs are currently under review.

The case of the European Union is particular as the opening of borders and the recognition of qualifications between member countries requires a common framework for training specialists. However, the variations in training systems still require a lot of work to achieve a new equivalent system. The length of the residency programs varies from 5 to 8 years, with a duration of 5 to 6 years in Spain and Italy. In other countries, as the United Kingdom, Germany and the Netherlands, residency training consists of 2 years of common trunk and 4 years of training in the area of interest14,15.

Argentina is a country with 45 million people and low population density. Although most of the population lives in urban areas, there are only 8 cities with more than 500,000 inhabitants. In addition, 38.9% live in the City of Buenos Aires and its metropolitan area. At present, there are 34 centers in the capital city that offer the possibility of training professionals in general surgery, with 94 positions available per year. Specialization within postresidency training programs and fellowships are also available in bariatric surgery, cardiovascular surgery, colon and rectal surgery, head and neck surgery, gastrointestinal surgery, surgical oncology, pediatric surgery, plastic surgery, pediatric and maxillofacial surgery, thoracic surgery, esophageal and gastroduodenal surgery, hepato-biliary-pancreatic surgery, abdominal wall surgery, percutaneous intervention procedures and minimally invasive surgery, breast surgery, urology, kidney and pancreas transplant surgery, gastrointestinal endoscopy, and phlebology and lymphology.

Those entering medical residency programs over the last few years belong to the so-called “Generation Y” (born between 1980 and 2000). They grew up in the digital age and pursue constant changes and concrete objectives. Work-life balance is one of their primary goals. They consider that the residency program in general surgery requires total work commitment and that the reputation and payment do not provide sufficient compensation. They demand flexible working hours model and an environment where family planning is possible. Over the past few years, several countries have reported a progressive decline in the number of applicants for training in surgery, reflecting the clear contrast of needs: on the one hand, a new generation demanding instant pleasure, with short-term goals and early socioeconomic independence, and, on the other hand, a training program that is becoming longer and less flexible16,17. In the United States the demand for positions in general surgery has decreased by 25% over the past two decades. In addition, only 18% of those entering the program expressed the intention of specializing in general surgery18.

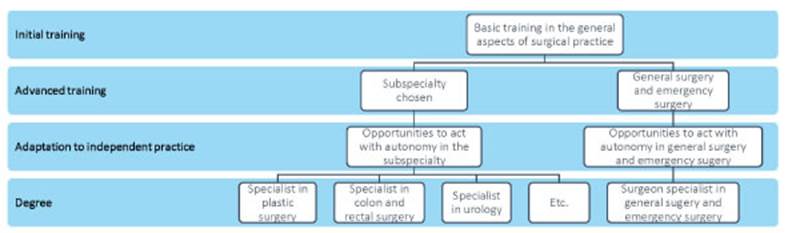

In order to develop deeper knowledge and skills in the area of interest, we suggest reducing the length of the training area, thus increasing the efficacy of the system. Some of the original strategies developed by this work group are (Fig. 1):

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the training program proposed

A 5-year program with the 2+3 model

The initial period comprises 24 months of basic training covering the general aspects of surgical practice. The second period of advanced training will provide thorough training in the subspecialty chosen. Certification will be granted upon completion of 5 years of training.

An early model of subspecialization as the one proposed requires solidarity among all the services and institutions, which must organize the migration between centers to ensure proper advanced training of the participants to maximize the use of human resources. In this way, training is based on objectives and not on the resources provided by a single institution.

Adaptation to independent practice

In the last year of the 5-year program trainees will have the opportunity to act as attending surgeons, replacing the current function of the chief resident. In this way, postgraduate year 5 residents would gain autonomy in the safe environment of the training institution.

Recategorization of general surgery and emergency surgery

General surgery, conceived as a subspecialty, would regain its status as an objective and no longer a pathway to become a subspecialist. It is of utmost importance to train specialists capable of effectively addressing the variety of conditions in which general surgeons have to deal with as the main work force in the surgical area. They will also act as the gate to the health system providing the first emergency care.

Regulation of vacancy opening

Training of specialists must be determined by the demands of the different profiles of surgeons, and by the interests of trainees. Therefore, the human resources available in specific subspecialties must be regularly reviewed and the number of vacancies in each subspecialty must be adjusted to meet the needs. The creation of an online registry of professionals, to be updated by each institution on a regular basis, would facilitate the task.

After analyzing the results, we observed that a high proportion of those respondents who completed their training program as general surgeons gave up working exclusively as such and decided to move to other surgical subspecialties. A smaller percentage moved to non-surgical specialties or to medical jobs not related with medical practice.

We can then conclude that the resources allocated to training are scattered and diluted because, nowadays, to be certified as a “general surgeon” seems to be more a means rather than an end for some trainees. The requirement to complete training to access a surgical subspecialty poses a dilemma: is it worth investing time and resources in trainees who will never practice general surgery? This requires restructuring of the training system to optimize the allocation of resources.

Acknowledgments:

We are grateful to Daniel E. Tripoloni for providing assistance with statistical analysis, Mercedes Canaro for assisting with data collec tion. and M. Valentina Sarsur for text editing.

REFERENCES

1. Polavarapu H, Kulaylat A, Sun S, Hamed O. 100 years of surgical education: The past, present, and future. B Am Coll Surg. 2013; 98(7):22-7. [ Links ]

2. Glorio R, Carbia S. Análisis histórico legal de las residencias médi cas y el residente. Dermatol Argent. 2014; 20(1):67-71. [ Links ]

3. Pautas Generales para los Programas de Residencia en Cirugía General. En: http://aac.org.ar/imagenes/residencias/pautas.pdf [ Links ]

4. Coleman J, Esposito T, Rozycki G, Feliciano D. Early Subspecializa tion and Perceived Competence in Surgical Training: Are Residents Ready? J Am Coll Surg. 2013; 216: 764-73. [ Links ]

5. Debas H, Bass B, Brennan M, Flynn T. American Surgical Associa tion Blue Ribbon Committee Report on Surgical Education: 2004. Ann Surg. 2005; 241(1). [ Links ]

6. Mattar S, Alseid A, Jones D, Jeyarajah DR, et al. General Surgery Residency Inadequately Prepares Trainees for Fellowship Ann Surg. 2013; 258:440-9. [ Links ]

7. Klingensmith M, Potts J, Merrill W, Eberlein T, et al. Surgical Trai ning and the Early Specialization Program: Analysis of a National Program. J Am Coll Surg . 2016; 222(4):410-6. [ Links ]

8. Cullinan D, Wise P, Delman K, Potts J. Interim Analysis of a Pros pective, Multi-Institutional Study of Surgery Resident Expe rience with Flexibility in Surgical Training. J Am Coll Surg. 2018; 226(4):425-31. [ Links ]

9. Richardson J, Buckley B, Shabahang M, Giles H, et al. From Tran sition to Practice to Mastery in General Surgery. B Am Coll Surg . 2018; 103(7):10-6. [ Links ]

10. Santos E, Salles G. Are 2 Years Enough? Exploring Technical Skills Acquisition among General Surgery Residents in Brazil. Teach Learn Med. 2016; 0( 0):1-9. [ Links ]

11. Tarasevich T. Surgical training in Russia. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007; 89:240-1. [ Links ]

12. Riaño D, Rincón D. La residencia en Cirugía General: Re flexión y evaluación en Colombia. En: http://bdigital.unal.edu.co/51257/1/80850273.2015.pdf [ Links ]

13. Kurashima Y, Watanabe Y, Ebihara Y, Murakami S. Where do we start? The first survey of surgical residency education in Japan. Am J Surg. 2016; 211(2): 405-10. [ Links ]

14. Dumon K, Traynor O, Broos P, Gruwez J. Surgical education in the new millennium: the European perspective. Surg Clin N Am. 2004; 84: 1471-91. [ Links ]

15. Borel-Rinkes I, Gouma D, HammingSurgical J. Training in the Netherlands. World J Surg. 2008; 32:2172-7. [ Links ]

16. Kleinert R, Fuchs C, Romotzky V, Knepper L, Wasilewski ML3, Schröder W, et al. Generation Y and surgical residency ± Pas sing the baton or the end of the world as we know it? Results from a survey among medical students in Germany. PLoS ONE 2017. [ Links ]

17. Schlitzkus L, Schenarts K, Schenarts P. Is Your Residency Program Ready for Generation Y? J SurgEducn. 2010; 67(2). [ Links ]

18. Klingensmith M, Awad M, Delman K. Deveney. Early results from the flexibility in surgical training research consortium: resident and program director attitudes toward flexible rotations in senior residency. J Surg Educ. 2015; 72(6). [ Links ]

Received: May 28, 2020; Accepted: September 21, 2020

texto en

texto en