Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista argentina de cirugía

versión On-line ISSN 2250-639X

Rev. argent. cir. vol.113 no.1 Cap. Fed. abr. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.25132/raac.v113.n1.1490.ei

Articles

Acute cholecystitis in a left sided gallbladder safely managed by laparoscopic surgery

1 Departamento de Cirugía General. Sana torio El Carmen. Salta. Argentina.

2 Departamento de Ci rugía General. Hospital San Bernardo. Salta. Argentina.

3 Departamento de Ci rugía General. Hospital Papa Francisco. Salta. Argentina.

The gallbladder is normally found beneath the junction of the hepatic segments 4 and 5. The round ligament divides segment 4 from segments 2 and 3 of the left liver lobe. The first case report of LSGB was published in 18861; since then, not more than 150 cases have been published in the literature2.

The universally accepted definition for a LSGB is a gallbladder located to the left of the round ligament, attached to de caudal surface of segment 3, without situs inversus viscerum3. Usually, LSGB is an incidental finding during elective cholecystectomy, and presents a technical challenge due to the difficulty of recognizing the anatomical structures and the greater risk of producing bile duct injury during the procedure4.

Only a few cases of early laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis in a left-sided cholecystectomy have been published in the literature5.

A 24-year-old male patient was admitted in the emergency department for abdominal pain in the right hypochondriac region, with positive Murphy´s sign. The laboratory tests showed white blood cell count of 14.2/ mm3. There were no signs of cholestasis, with normal direct and indirect bilirubin levels. The abdominal ultrasound revealed a distended gallbladder, with thickened walls and a gallstone in the gallbladder neck; the bile ducts were not dilated. A diagnosis of acute cholecystitis was made, and laparoscopic cholecystectomy was scheduled for the following day.

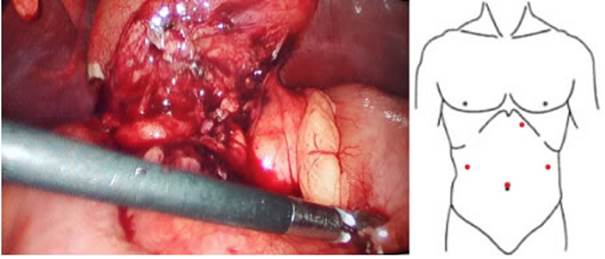

On exploratory laparoscopy, the liver was enlarged, with signs of steatosis. The gallbladder was located to the left of the round ligament. With this finding, the working ports were modified; a 10-mm trocar was placed in the epigastrium, to the left of the round ligament, and two 5-mm accessory ports were inserted in each lumbar region (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Laparoscopy; the gallbladder is located to the left of the round ligament. Alternative position of the working ports

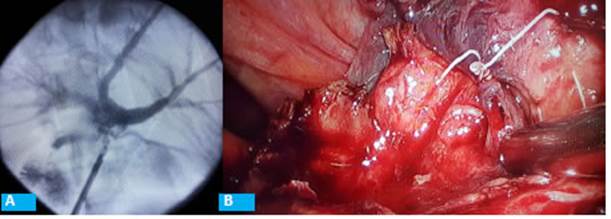

The gallbladder was punctured, evacuating purulent fluid and a cholangiography was performed through this route, confirming the finding of a LSGB, with the cystic duct ending at the left of the main bile duct (Fig. 2).

The gallbladder neck was then dissected, until exposing the cystic duct with blunt maneuvers and electro cautery. A new cholangiography was performed via the trans-cystic route, which demonstrated complete and clear main bile duct, with adequate flow of contrast media into the duodenum. The cystic duct ended to the left of the main bile duct (Fig. 3 A). The cystic duct was ligated with nylon endoloop and cholecystectomy is performed from the neck to the bottom (Fig. 3 B).

Figure 3 A: Transcystic cholangiography. B: Cystic duct stump with nylon endoloop; gallbladder resection starting

The patient was discharged 24 hours after the procedure, without complications. After two years of follow-up, the patient has had no symptoms or signs of complications.

Left-sided gallbladder is a rare anatomical variant, usually found during a laparoscopic cholecystectomy due to symptomatic cholelithiasis. There are two hypotheses about the embryological origin of a LSGB. The first hypothesis suggests an early migration and attachment of the gallbladder diverticulum to the surface of segment 3 of the liver, assuming that the cystic duct is in normal anatomical position on the right of the bile duct. The second theory is that the gallbladder diverticulum arises directly from the left side of the common bile duct and is attached to the ipsilateral liver surface3. The preoperative diagnosis of a LSGB is extremely rare, since the clinical presentation does not differ from that of a patient with right-sided gallbladder. Pain, for example, is almost always located at the epigastrium and right hypochondriac region4. One explanation is that visceral nerve fibers do not transpose with the gallbladder6.

Abdominal ultrasound is the first imaging test commonly used for the diagnosis of symptomatic cholelithiasis and its complications (cholecystitis, common bile duct lithiasis, cholangitis, pancreatitis) but has very low sensitivity to detect anatomical variants of the bile duct. More complex tests such as multislice computed tomography scan and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography have higher sensitivity for the diagnosis of these anomalies but are not routinely ordered before cholecystectomy. For this reason, LSGB is almost usually diagnosed during cholecystectomy. Despite its low prevalence it is associated with high rates of bile duct injuries (7.3%)7.

Left-sided gallbladder can be associated with other types of anatomical variants of the bile duct and portal venous system such as anomalous cystic duct insertion, double common bile duct, retroportal common bile duct, and abnormalities of the pancreaticobiliary junction. Different case series of LSGB reported a cystic duct joining the common hepatic duct on the right side in approximately 65% of the cases, and on the left side in 10% as in our case. In a lower percentage of cases, the cystic duct joins the left hepatic duct (9%), the right hepatic duct (7%) or one of its branches7. These abnormalities bring technical challenges when performing a cholecystectomy and increase the risk of complications during this procedure. Bile duct injury is the most feared complication and is almost invariably associated with a poor dissection technique. The oblique lie of the LSGB and the projection of the cystic duct in front of the common hepatic duct contribute to this risk. The dissection of the gallbladder from the gallbladder bed is often difficult and also exposes the main bile duct to the risk of iatrogenic injuries8.

Although a LSGB can be adequately addressed using the usual technique, two variants can be used at the beginning of laparoscopy to help the surgeon operate more comfortably on an incidentally found LSGB. One possibility is the different positioning of the working ports, changing a 5 mm-trocar on the right lumbar region to the left side and the placing the epigastric port to the left side of the falciform ligament. Another variant is the early division and retraction to the right of the falciform ligament, removing it from the surgeon’s vision and improving exposure. However, nothing replaces a safe dissection of the Callot’s triangle, exposing the cystic duct and the cystic artery until they are the gallbladder bed to achieve a critical view of safety9.

Many authors recommend other technical variants to approach a LSGB. Immediate conversion to open surgery may be an appropriate option if the surgical team does not have sufficient experience in advanced laparoscopic surgery. However, conversion to open surgery also requires a proper dissection to obtain the critical view of safety. Other authors propose the “fundus-first” dissection technique4,8. In our opinion, as this technique has a higher rate of serious bile duct injuries in the normally positioned gallbladder, the risk of iatrogenic injury may be even greater in the presence of a LSGB10. In the case of preoperative diagnosis of LSGB, the French position is recommended, placing the surgeon between the patient’s legs for a more comfortable and ergonomic position.

The use of intraoperative cholangiography in our daily practice allows the early diagnoses of bile duct injuries and reduces the risk of serious bile duct resections if it is properly interpreted. Even more, the diagnosis of anatomical variants and the presence of common bile duct stones can be made11. For this reason, we strongly recommend performing a cholangiography when a LSGB is found. Cholangiography by direct puncture of the gallbladder is another important tool to obtain an acceptable image of the biliary anatomy and for a safe approach of the Callot´s triangle in this type of cases.

The insertion of a drain tube (cholecystostomy) in case of cholecystitis instead of dissecting the gallbladder hilum is a valid option when a LSGB is found and the surgical team does not have enough experience. This allows performing more complex imaging tests, as magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, to plan a better surgical approach with greater knowledge about the biliary anatomy and to offer the patient a surgical team with more expertise in this type of surgery.

Left-sided gallbladder is a rare bile duct abnormality, almost invariably diagnosed during a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The technical difficulties offered by this incidental finding significantly increase the risk of complications, particularly of main bile duct injury. Some modifications of the classical technique can help to safely complete this procedure, including the positioning of the laparoscopic ports, the section and retraction to the right of the falciform ligament and the careful dissection of the Callot´s triangle to obtain a critical view of safety. Undoubtedly, the use of intraoperative cholangiography is a valuable tool in these cases and its systematic use should be considered.

Referencias bibliográficas /References

1. Hochstetter F. Anomalien der Pfortader and der Nabelvene in Verbindung mit Defect oder Linkslage der Gallenblase. Arch Anat Entwick. 1886:369-84. [ Links ]

2. Moo-Young TA, Picus DD, Teefey S, Strasberg SM. Common bile duct injury following laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the setting of sinistroposition of the gallbladder and biliary confluence: a case report. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010; 14:166-70. [ Links ]

3. Gross RE. Congenital anomalies of the gallbladder: a review of one hundred and forty-eight cases, with report of a double gall bladder. Arch Surg. 1936; 32:131-62. [ Links ]

4. Colovic R, Colovic N, Barisic G, Atkinson HDE, Krivokapic Z. Left-sided gallbladder associated with congenital liver cyst. HPB (Oxford). 2006; 8: 157-8. [ Links ]

5. Hirohata R, Abe T, Amano H, Kobayashi T, Nakahara M, Ohdan H, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis in a patient with left-sided gallbladder: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2019; 5:54. [ Links ]

6. Sadhu S, Jahangir TA, Roy MK. Left-sided gallbladder discovered during laparoscopic cholecystectomy in a patient with dextrocar dia. Indian J Surg. 2012; 74:186-8. [ Links ]

7. Pereira R, Singh T, Avramovic J, Baker S, Eslick G and Cox M. Left-sided gallbladder: a systematic review of a rare biliary anomaly. ANZ J Surg. 2019; 89(11): 1392-7. [ Links ]

8. Abongwa HK, De Simone B, Alberici L, Iaria M, Perrone G, Tarasco ni G, et al. Implications of Left-sided Gallbladder in the Emergency Setting: Retrospective Review and Top Tips for Safe Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2017; 27:220-7. [ Links ]

9. Strasberg SM, Brunt LM. Rationale and use of the critical view of safety in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2010; 211:132-8. [ Links ]

10. Strasberg SM, Gouma DJ. ’Extreme’ vasculobiliary injuries: asso ciation with fundus-down cholecystectomy in severely inflamed gallbladders. HPB (Oxford) . 2012; 14:1-8. [ Links ]

11. Álvarez FA, de Santibañes M, Palavecino M, Sánchez Clariá R, Ma zza O, Arbúes G, et al. Impact of routine intraoperative cholangio graphy during laparoscopic cholecystectomy on bile duct injury. Br J Surg. 2014; 101: 677-84. [ Links ]

Received: April 16, 2020; Accepted: October 14, 2020

texto en

texto en