Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista argentina de cirugía

versión impresa ISSN 2250-639Xversión On-line ISSN 2250-639X

Rev. argent. cir. vol.113 no.2 Cap. Fed. jun. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.25132/raac.v113.n2.eras05rem.ei

Articles

Implementation of an ERAS® program

1 Sección de Colo proctología, Servicio de Cirugía General, Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina.

2 Servicio de Anestesio logía, Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Introduction

Enhanced recovery programs were introduced by the end of the last century to standardize perioperative care in patients undergoing colorectal surgery1,2. Initially, independent groups applied measures based on the best evidence available at that time, which later evolved into the ERAS® Society with carefully designed guidelines of recommendations that are periodically reviewed and widely disseminated3-5. ERAS® involves a multidisciplinary approach using multimodal perioperative care pathways before, during and after surgery, designed to minimize the physiologic stress of a surgical procedure and optimize the perioperative management6. Several studies have shown a significant reduction in length of hospital stay after implementing ERAS® programs in colorectal surgery when compared to standard care7- 9. Nevertheless, length of hospital stay is affected by the variability in implementing care pathways in the different areas involved (surgery, anesthesia, nursing, etc.)10. This variability, expressed as the percentage of elements of care of the ERAS program delivered to each patient recorded is known as adherence.

Gustaffson et al.10 demonstrated an inverse correlation between the percentage of adherence to the recommendations and length of hospital stay. They also observed a significant reduction in length of hospital stay and readmission rate in those patients with adherence to the recommendations ≥ 70% compared with those with adherence ≤ 50%. Similarly, the benefits of ERAS are associated with the implementation of the entire protocol (creation of a multidisciplinary team, systematic recording of the process of care and use of these registries by the medical team to improve the implementation of the program) and not with the implementation of individual ERAS protocol elements11. For this reason, the distinctive feature of ERAS is the perioperative management based on the main four elements of the cycle of continuous improvement: a) plan an intervention for patient’s care from the analysis of baseline data, b) act on the plan made, c) audit the effect of the plan and d) adjust perioperative care according to the new data analysis12.

The experience of Hospital Italiano

The implementation of the ERAS program at Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires began in November 2015 with the incorporation of the first patient in the database. Since then, all the patients undergoing elective surgery with resection of the colon, rectum, restoration of intestinal continuity, resection of pelvic tumors, cytoreductive surgeries and other less common procedures in the spectrum of coloproctology were recorded. Initially, the core work group was made up of an anesthesiologist, a surgeon, a nurse, and a nutritionist. Then, other participants as kinesiologists and intensivists were incorporated.

The anonymized data were recorded in an online database accessible to the team called the ERAS Interactive Audit System (EIAS; www.erassociety.org, Encare, Kista, Sweden)13. Each record includes a set of heterogeneous variables: e.g., age, sex, body mass index, ASA classification, preoperative nutritional status, comorbidities, preoperative diagnosis, surgical approach, type of surgery, length of surgery, type of anesthesia, multimodal analgesia, time to mobilization after surgery, tolerance to oral intake, and length of hospital stay. Complications are recorded according to the Clavien-Dindo classification14 within 30 days after surgery. Length of hospital stay is defined as the number of days from the index surgery to hospital discharge. Readmission is defined as any new hospitalization within 30 days of the index surgery. The audited variables are compiled from the information available in the electronic medical record and in the dairy with postoperative information completed by the patients or their relatives during hospitalization. The instruction for filling out the patient’s diary is given during the preoperative education stage. Data not collected through these channels are obtained in person by the team nurse specifically trained for this task who is also in charge of the continuous registration in the database. Missing data are considered as a lack of adherence to that particular element of care. The overall adherence to the program is calculated as the average adherence to all the ERAS elements of care for colonic surgery3 and rectal surgery15 applied to each patient and is expressed as a percentage5. Our program does not count with any special allocation of financial resources from the institution or from team members for its implementation.

The team holds weekly meetings involving at least one surgeon, anesthesiologist, nutritionist and nurse, and discusses aspects of the implementation of the program. The mains goals of the meetings are to improve adherence while maintaining the interdisciplinary communication. The cycle of continuous improvement (plan, act, audit and adjust) is carried out in the meetings, where the team analyzes the database, observes adherence to the elements of care of the guideline to detect errors and prepares corrective action plans tailored to specific needs. The cycle of continuous improvement also involves nurturing the motivation of the team members. The implementation of an ERAS program has shown difficulties in maintaining commitment and dedication to compliance with the elements of care over time, conspiring against the adherence to the program16 and ultimately affecting postoperative outcomes.

Results of the implementatio of an ERAS® program

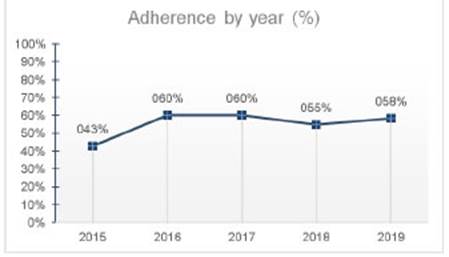

From November 2015 to the present, data from 1331 patients were recorded; median age was 63 years and 51.5% were women. Median length of hospital stay was 4 days and median readmission rate was 7.3%. Adherence in the pre-ERAS stage was 37% (68% in the preoperative period, 44% in the intraoperative period, and 18% in postoperative period), and was 56% in the ERAS stage (88%, 60% and 39%, respectively). A similar variation in the average adherence was observed in all the centers that implemented ERAS programs in Latin America between 2014 and 201812.

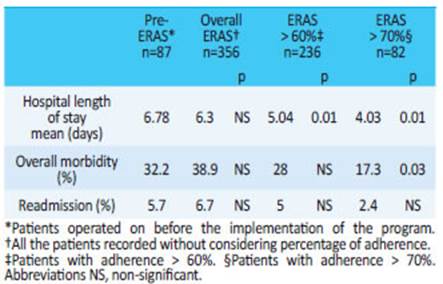

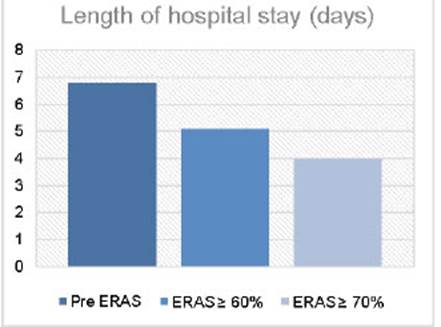

Our experience during the implementation of the program in 2018 is described in Table 1. The analysis includes three variables directly related with the objectives of the ERAS program: length of hospital stay, overall morbidity and readmission rate. Eighty-seven consecutive patients operated on before the first record in the database (pre-ERAS) were compared with the first 356 consecutive patients who underwent surgery and were recorded during the ERAS program. The most common interventions were analyzed (right colon resection, left colon resection, sigmoid colectomy, anterior resection of the rectum and abdominoperineal resection). There were no significant differences in the global evaluation of the three variables analyzed. However, in the analysis of the subgroup of patients with an adherence ≥ 60% (n = 236), length of hospital stay was reduced by 1.77 days (95% CI; 0.5-3 days) compared with the pre-ERAS group. This difference represents an economic benefit of 417 hospital bed days. Furthermore, in the subgroup of patients with an adherence ≥ 70% (n = 82), the difference in the average length of hospital stay is even greater, reaching 2.8 days (95% CI, 0.96-4.7 days), which represents savings of 229 hospital bed days. These results indicate that the high adherence to the ERAS program at Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires is associated with significant improvement in length of hospital stay compared with standard care17 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Comparison between mean length of hospital stay in the pre-ERAS stage and ERAS stage with different percentage of adherence at Hos pital Italiano de Buenos Aires.

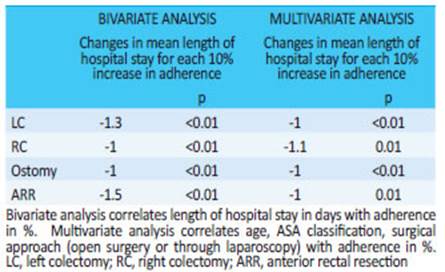

Table 2 shows the average variation in length of hospital stay in days for the most common procedures included in the program for each 10-point increase in adherence. There is an inverse association between adherence and length of hospital stay, emphasizing the relevance of implementing the greatest number of elements of care for each patient to reduce the length of hospital stay (achieving the greatest adherence possible).

Adherence to the implementation protocol

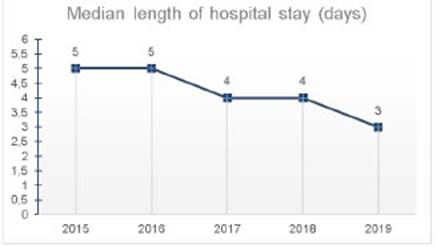

The ERAS Compliance Group conducted a multicenter study on 2000 patients undergoing colorectal surgery; the adherence to the program ranged from 71.5% to 92.8%, with a median length of hospital stay of 6 days (IQR 4-8) and a readmission rate of 9.2%18. Figure 2 illustrates the time course of adherence in our hospital during the first 5 years of the program. Figure 3 displays median length of hospital stay over the same time period. Despite the overall adherence was relatively low, median length of hospital stay was short compared with some published clinical trials on ERAS19,20. The overall adherence to the program remained relatively stable over the years, but there was a significant decrease in the length of hospital stay. This may be the result of under-reported data: that is, a greater number of elements of care could have been complied than those duly recorded. Under-reporting is an important limitation to achieving optimal implementation of the program, as it is interpreted by the EIAS as a lack of adherence to the care pathway. This situation may be due to different reasons. First, the size of the database complicates data entry, as it requires at least 159 variables per patient (including 287 variables if complications or other specific situations are recorded). Second, the availability of data does not occur at the same time: it is often necessary to collect information from different sources, access the database several times and enter coded data. Third, the workload is determined by the volume of surgeries and the workload imposed by data recording far exceeds the operational capabilities of the professional dedicated to this task. In particular, our work team has one person working part-time to record data in the database. Fourth, when data are uploaded untimely, the cycle of continuous improvement cannot progress optimally as it is not possible to make the appropriate corrections when the information is not timely interpreted. In this sense, the lack of human or economic resources, or both, at the institutional level constitutes a barrier to the adequate implementation of an ERAS program16. Fifth, this also depends on the ability of the recorder to properly interpret the data. As the perioperative period is a multidisciplinary process, recording data involves specific technical knowledge of different specialties that may exceed the ability of a single professional to interpret all the information. In our experience, this situation has led to errors in the registry that subsequently impaired the ability and quality of the analysis. In this way, the benefit could be greater if we apply the same multidisciplinary approach that guides our health care practice to data collection. If each member of the team could enter the information according to their field of expertise, this would help to improve the quality and speed of recording the data. Finally, the low quality of the evidence available for certain recommendations of the elements of care, together with the adverse effects that these elements produce in some patients, could raise resistance to their implementation among some members of the team. In our experience, postoperative oral nutritional supplementation has been associated with high rates of nausea, vomiting and diarrhea, which led us to systematically discontinue its use.

Figure 2 Mean length of hospital stage by year of implementation of the pro gram. The time course of the median length of hospital stay in each year the program was implemented is observed.

The aforementioned example allows us to mention the most recent difficulty we have perceived when assessing adherence to the recommendations of the ERAS® Society clinical guidelines4 using the EIAS. The auditing system includes specific variables that contribute to estimating adherence and assess the care provided by the team regardless of the patient’s outcome or condition (e.g., use of antibiotics during induction of anesthesia or of measures to maintain normothermia during the intraoperative period). However, during postoperative care it may be difficult to determine whether the failure to comply with a recommendation is due to lack of compliance by the team or is the result of a clinical outcome because of, for example, the use of oral nutritional supplementation (e.g., intolerance to liquid diet). In specialized referral centers, where unusual major surgical procedures (pelvic exenteration, cytoreductive surgery) are common, the difficulty in complying with these recommendations is greater. The problem in determining whether adherence to a care pathway represents an authentic clinical outcome could hinder the analysis of the relationship between adherence and length of hospital stay.

Conclusion

After five years of working in an ERAS program, we understand that multidisciplinary teamwork with effective communication is essential to carry out the cycle of continuous improvement. Likewise, reliable recording of data is essential. We have found that overall adherence to the specific recommendations has resulted in better postoperative outcomes, with shorter length of hospital stay, low morbidity rate and fewer readmissions. The implementation and sustainability of the program depends on the institutional support to provide the necessary resources and on the personal commitment and motivation of each team member in the different stages of the program.

Referencias bibliográficas /References

1. Basse L, Hjort Jakobsen D, Billesbølle P, Werner M, and Kehlet H. “A clinical pathway to accelerate recovery after colonic resection,”. Ann Surg. 2000;232, (1,): 51-7. [ Links ]

2. Kehlet H. “Multimodal approach to control postoperative pathophysiology and rehabilitation,”. Br J Anaesth. 1997; 78(5): 606-17. [ Links ]

3. Gustafsson UO, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in elective colonic surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society recommendations. Clin Nutr.2012; 31(6): 783-800. [ Links ]

4. Gustafsson UO, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in elective colorectal surgery: enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) Society Recommendations: 2018. World J Surg. 2019; 43(3): 659-95. [ Links ]

5. Lassen K, et al. Consensus review of optimal perioperative care in colorectal surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Group recommendations. Arch Surg. 2009; 144(10): 961-9. [ Links ]

6. Ren L, et al. Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) program attenuates stress and accelerates recovery in patients after radical resection for colorectal cancer: a prospective randomized controlled trial. World J Surg. 2012; 36(2): 407-14. [ Links ]

7. Greco M, Capretti G, Beretta L, Gemma M, Pecorelli N, Braga M. Enhanced recovery program in colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Surg. 2014; 38(6): 153141. [ Links ]

8. Spanjersberg WR, Reurings J, Keus F, van Laarhoven CJ. Fast track surgery versus conventional recovery strategies for colorectal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev., 2011;no 2, p. CD007635. [ Links ]

9. Eskicioglu C, Forbes SS, Aarts M-A, Okrainec A, McLeod RS. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs for patients having colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009; 13(12): 2321-9. [ Links ]

10. Gustafsson UO, et al. Adherence to the enhanced recovery after surgery protocol and outcomes after colorectal cancer surgery. Arch Surg. 2011; 146(5): 571-7. [ Links ]

11. Ljungqvist O, Scott M, Fearon KC. “Enhanced Recovery after Surgery: A Review. JAMA Surg. 2017; 152(3): 292-8. [ Links ]

12. Loughlin SM, Álvarez A, Falcão LFDR, Ljungqvist O. The History of ERAS (Enhanced Recovery after Surgery) Society and its development in Latin America. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2020; 47: e20202525. [ Links ]

13. Website. ERAS Society. ERAS Interactive Audit System. Available at: Available at: http://www.eras-society.org . Accessed June 6, 2014. (Accessed Mar. 02, 2021). [ Links ]

14. Clavien PA, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009; 250(2): 187- 96. [ Links ]

15. Nygren J, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in elective rectal/ pelvic surgery: Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) Society recommendations. Clin Nutr. 2012; 31(6): 801-16. [ Links ]

16. Pearsall EA, et al. A qualitative study to understand the barriers and enablers in implementing an enhanced recovery after surgery program. Ann Surg. 2015; 261(1): 92-6. [ Links ]

17. Rossi G, et al. Two-day hospital stay after laparoscopic colorectal surgery under an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathway. World J Surg. 2013; 37(10): 2483-9. [ Links ]

18. ERAS Compliance Group. The Impact of Enhanced Recovery Protocol Compliance on Elective Colorectal Cancer Resection: Results from an International Registry. Ann Surg. 2015; 261(6): 1153-9. [ Links ]

19. Kennedy RH, et al. Multicenter randomized controlled trial of conventional versus laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer within an enhanced recovery programme: EnROL. J Clin Oncol. 2014; 32(17): 1804-11. [ Links ]

20. Vlug MS, et al. Laparoscopy in combination with fast track multimodal management is the best perioperative strategy in patients undergoing colonic surgery: a randomized clinical trial (LAFA-study). Ann Surg. 2011; 254(6): 868-75. [ Links ]

Received: March 15, 2021; Accepted: March 24, 2021

texto en

texto en