Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista argentina de cirugía

versión impresa ISSN 2250-639Xversión On-line ISSN 2250-639X

Rev. argent. cir. vol.114 no.2 Cap. Fed. jun. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.25132/raac.v114.n2.1583

Articles

Complicated gastric GIST. An unusual presentation

1 Sección Cirugía Gastroesofágica. Servicio de Cirugía General CMPF Churruca-Visca. Buenos Aires. Argentina

The incidence of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) has increased over the past 15 years due to their incidental diagnosis during gastrointestinal tract endoscopies and in the evaluation of anemic syndromes. They usually present as subepithelial lesions covered by normal mucosa, which may cause gastrointestinal bleeding and anemia due to ulceration. Other types of presentation are caused by compression and obstruction of the cardia and gastric outlet. The diagnostic value of endoscopic biopsy is low. Imaging tests as computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are useful to evaluate tumor location, size, characteristics, and particularly to differentiate between endophytic and exophytic growth, which will have implications when planning the type of approach. Endoscopic ultrasound usually provides the definitive diagnosis by showing an echo-poor homogeneous lesion with well-defined borders originating in the 2nd layer (muscularis mucosa) or 4th layer (muscularis propria). In the case of resectable lesions with high clinical and radiological suspicion, a biopsy is not necessary to determine the appropriate management1. If necessary, fine-needle biopsy can be performed during endoscopic ultrasound2.

We describe an atypical presentation with requirement of urgent hospitalization.

A 61-year-old female patient without relevant clinical conditions and who had undergone conventional cholecystectomy 6 years before visited the emergency department due to cervicalgia associated with dizziness and was medicated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSADs) by the orthopedic surgeon on duty. She sought medical care again 48 hours later because the symptoms persisted and presented an episode of coffee ground vomitus. She did not complain of abdominal pain, melena or weight loss.

On admission, the patient was alert; her blood pressure was normal, and the heart rate was 106 beats per minute. On physical examination she presented intense pallor; the abdominal palpation was painless and normal. The laboratory tests showed hematocrit of 7.6% and hemoglobin level (Hb) of 2.4 g/dL.

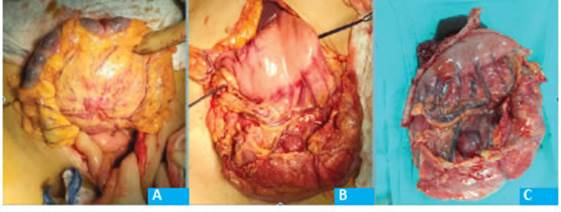

She received a transfusion of 3 units of packed red blood cells and underwent upper gastrointestinal tract endoscopy, which reported coffee ground patches and a 3-cm fistulous orifice in the mid region of the gastric body, over the greater curvature. The orifice communicated with the mucosa, which had a granular and necrotic appearance, was friable and with hard consistency at the moment of taking the biopsy. Food residues were visible (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 A: Gastric fistulous orifice. B endoscopic vision of the tumor cavity. C: CT scan showing heterogeneous mass with fluid-air level, calcifications and a well-defined capsule with neoformation of vessels (arrows)

The endoscopic findings were similar to those observed in video-assisted necrosectomies in pancreatic walled-off necrosis (WON) due to severe acute pancreatitis.

The evaluation was completed with a CT scan which showed a heterogeneous lesion of approximately 14 cm in diameter. The lesion had air-fluid level, calcifications, and a capsule of defined borders with neoformation of vessels. There were no abnormalities or infiltration of the pancreas, and the transverse colon had caudal displacement with no signs of infiltration. The liver and lungs were free of metastases.

During hospitalization the patient required transfusion of 2 additional units of packed red blood cells to optimize the hemoglobin levels and started enteral and parenteral nutrition for 8 days to improve the nutritional status before surgical treatment.

The pathology examination of the biopsy reported the presence of spindle-shaped cells and necrosis. Immunostaining: CD 34+, Cd 117+, Ki-67 15- 20%. The findings were suggestive of high-risk GIST.

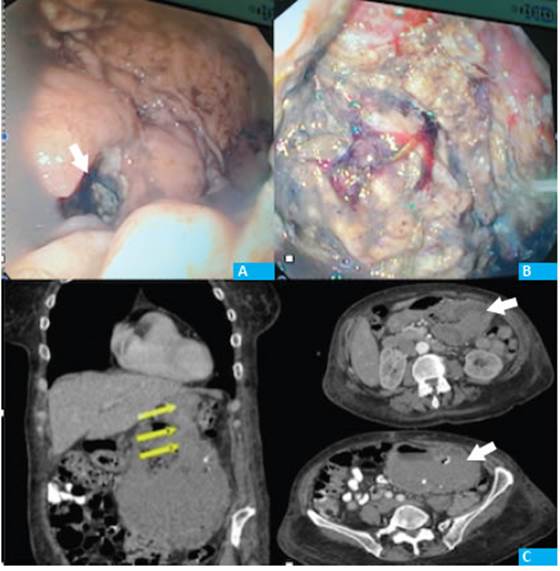

The tumor was approached via midline laparotomy. A large mobile lesion was observed in the greater curvature, with scarce intragastric component. The lesion was located between the sheets of the gastrocolic ligament, in close contact with the vessels of the middle colic pedicle without infiltration of the wall of the transverse colon. There were no additional abnormal findings.

The greater omentum was divided, the gastrocolic ligament was opened on both sides of the tumor and the cavity was accessed. The distance to the body of the pancreas was adequate. An atypical wedge resection was performed; a lozenge-shaped segment of the grater curvature was excised using mechanical stapler with staple line reinforcement. En bloc resection of the lesion was completed, preserving the integrity of the tumor capsule along with a 15-cm segment of transverse colon with its mesocolon, and the root of the middle colic pedicle was ligated (Fig. 2). A side-to-side bowel anastomosis was performed with linear mechanical stapler.

The patient evolved with favorable outcome. She started tolerating food 48 hours later and was discharged on postoperative day 6 because the preoperative swab tested positive for COVID-19.

The pathology examination reported a 14 cm × 13 cm whitish tumor with intramural foci of calcium. The surgical margins were clear (preservation of 1.5 cm margin of normal-looking mucosa). Microscopic examination: ulcerated spindle-cell type tumor. Necrosis:15%. 9/10 mitosis AGC. High histologic grade (G2).

The case was presented in the Tumor Committee to receive adjuvant therapy with imatinib.

Our department approaches gastric GISTs by laparoscopy in > 90% of cases, and the procedure has been successfully completed by this approach in 100% of them. The benefits are undeniable in terms of improved postoperative pain and patient comfort, reduced postoperative ileus and length of hospital stay.

The advantage of requiring a minimum clear margin of 1 cm and the lack of a requirement for lymph node resection3 allows for atypical wedge gastrectomy in most cases, preserving the healthy organ and the continuity of the gastrointestinal tract. In case of lesions in the pyloric antrum, we have performed antrectomies to avoid possible stenosis. Tumors below the cardia are less common but more challenging; in these cases, intragastric and endoscopic-assisted approaches are very useful. It is essential to avoid manipulation of the tumor and to preserve its pseudo-capsule intact. Rupture implies the possibility of peritoneal seeding, casting a shadow over the oncologic prognosis6.

Therefore, tumor size is the main factor to consider when planning the surgical strategy. There is no agreement on the cut-off value of tumor size for choosing one strategy over the other. Laparoscopic surgery is safe, as long as it can fulfill the same oncologic criteria as open surgery3. Asymptomatic patients with tumors < 2 cm can be monitored without resection, especially in elderly patients or those with high surgical risk.

In tumors > 5 cm4 laparotomy should be considered if there is risk of tumor rupture, a threatening complication. This is one of the most important prognostic factors, together with tumor size, mitotic index and the organ affected (gastric tumors have a better prognosis than those of the small bowel and rectum)5.

High-risk GISTs should receive adjuvant therapy due to their high risk of relapse. Adjuvant therapy with imatinib for 3 years is the standard treatment5. Molecular tests can detect mutations that modify this treatment, but they are not yet widely available in our country.

Referencias bibliográficas /References

1. Sánchez-Hidalgo JM, Durán-Martínez M, Molero-Payan R, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a multidisciplinary challenge. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(18):1925-41. [ Links ]

2. Kazuya A, Masafumi O, Tadashi K, Yuki S. Current clinical management of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(26):2806-17. [ Links ]

3. Correa JC, Morales CH, Sanabria A. Tratamiento quirúrgico de tumores del estroma gástrico: ¿es mejor el abordaje laparoscópico? Rev Colomb Cir. 2014;29:131-9. [ Links ]

4. Parab TM, DeRogatis MJ, Boaz AM, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a comprehensive review. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;10(1):144-54. doi: 10.21037/jgo.2018.08.20 [ Links ]

5. Casali P, N. Abecassis N.2, Bauer S, Biagini N et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO-EURACAN. Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018; 29 (Supplement 4): iv68-iv78. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdy095 [ Links ]

Received: March 06, 2021; Accepted: May 03, 2021

texto en

texto en