Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista argentina de cirugía

versión impresa ISSN 2250-639Xversión On-line ISSN 2250-639X

Rev. argent. cir. vol.115 no.1 Cap. Fed. mayo 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.25132/raac.v115.n1.1666

Articles

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding: risk factors of severity, need for emergency surgery and in-hospital Mortality

1 Servicio de Cirugía General y Coloproctología Clínica Modelo de Lanús. Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Introduction

Over the past few years, the presence of certain signs, symptoms and factors associated with a disease to determine its severity and predict its outcome has gained relevance1-4.

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) is not an exception to this interest. Nevertheless, the systematic determination of the factors associated with severe bleeding and other evolving variables is insufficient and has little evidence. Even today, medical experience and judgment are still important for staging and determining the outcome of LGIB5-9.

Understanding the risk factors for severe LGIB has several advantages, including the ability to predict severe episodes, establish rapid and aggressive treatment, admit patients to the intensive care unit (ICU), perform invasive diagnostic tests, predict emergency surgery, and estimate mortality1-8.

The aim of our study was to analyze the risk factors associated with severe bleeding, emergency surgery and in-hospital mortality (30 days) in patients with LGIB.

Material and methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study on consecutive patients evaluated by consultants, following the standards of our department for diagnosis and treatment. Two authors (JAL and MJL) participated in the evaluation of all severe cases. The population analyzed was made up of 2069 patients treated between January 1999 and December 2018. The inclusion criteria were age > 18 years, hematochezia confirmed by clinical examination and hospitalization for hemodynamic support. The exclusion criteria included upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) manifested as LGIB, anal bleeding or bleeding due to inflammatory bowel diseases, mortality due to associated diseases and not due to bleeding, and incomplete data.

Mild or moderate LGIBs were defined as melena, hematochezia or rectal bleeding, with or without hemodynamic changes. These cases can be easily compensated by the usual treatment measures. Once perianal causes have been excluded in our protocol, all these patients are hospitalized. Severe LGIB was considered in the presence of copious bleeding with hemodynamic decompensation, tachycardia, tachypnea, peripheral vasoconstriction, oliguria, sensory disturbances, hematocrit drop below 30%, metabolic acidosis and transfusion requirement. We analyzed thirteen variables during the first four hours of hospitalization to evaluate the risk of severe bleeding: age > 70 years, sex, history of cardiovascular disease, anticoagulation, blood pressure (BP) (< 90 mm Hg), heart rate (HR) (> 120 bpm), oliguria (< 20 mL/hour), massive hematochezia, hematocrit (< 30%), hemoglobin (< 7 g%), BUN (< 40%), creatinine level (> 1.3 mg%) and transfusion of two units of blood or greater. In critically ill patients, we also considered diverticular disease as a cause of bleeding to determine the factors associated with probability of surgery.

Those significant independent variables without collinearity underwent logistic regression analysis in relation with the outcome surgery. Emergency surgery and ASA grade were considered to evaluate mortality.

Data were incorporated into a Microsoft Excel 97® database and analyzed using R Core Team (2018) 4.0 statistical software package. All the variables included were dichotomized are expressed as frequency and percentage. The differences between groups were analyzed using the asymptotic test for comparing two proportions and, if the assumptions were not met, the chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used. A p value < 0.05 with a 95% confidence interval was considered statistically significant. A logistic regression analysis was considered with the outcome “surgery and mortality” including those independent categorical variables without collinearity (Cramer’s V coefficient).

The final results were used to construct a formula to predict the need for surgery. An internal validation of the formula was performed using bootstrapping technique.

Results

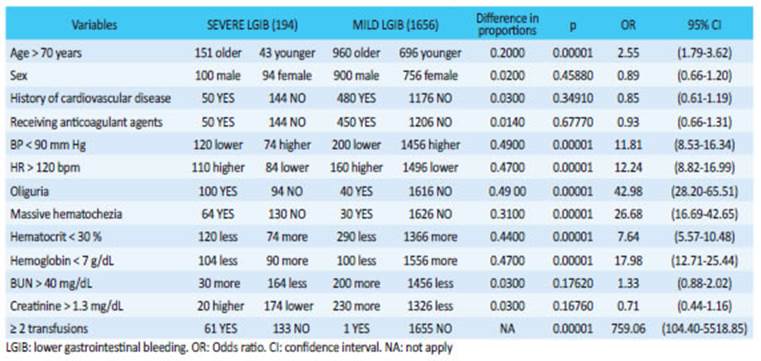

With the aforementioned criteria, 219 cases were excluded, leaving 1850 patients for the analysis; 194 were severe cases (10.5%) and 1656 were mild/ moderate cases (89.5%). Patients > 70 years, with HR > 120 beats/ min, BP < 90 mm Hg, oliguria, massive hematochezia, hematocrit < 30%, hemoglobin < 7 g% and need for transfusions were significantly more common in severe LGIB (Table 1).

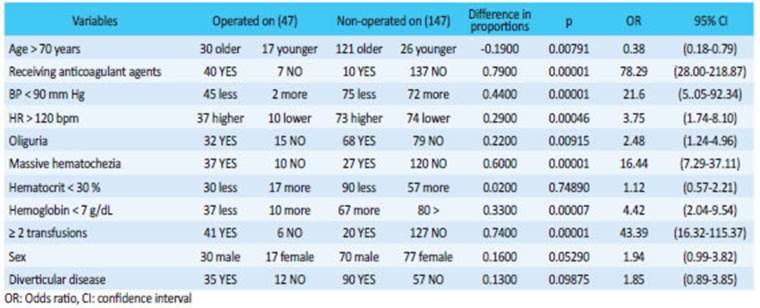

The 47 severe cases (24%) that underwent emergency surgery and the 147 severe cases (76%) that did not undergo surgery were analyzed separately. Those who underwent emergency surgery presented a statistically significant higher proportion of the following variables: age > 70 years, anticoagulation, hypotension, tachycardia, hemoglobin < 7 g%, oliguria, need for transfusion and massive rectal bleeding (Table 2).

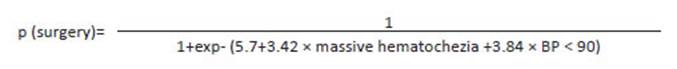

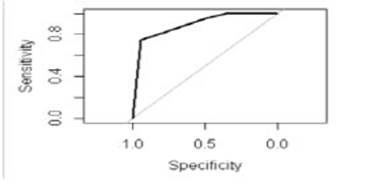

The four independent variables significantly associated with the outcome surgery (BP <90 mm Hg, oliguria, massive hematochezia and age > 70 years) underwent logistic regression analysis. The model run with the variables BP < 90 mm Hg and massive hematochezia showed the best explanatory quality with the highest sensitivity, specificity and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC) (Table 3).

These results were used to construct a formula to predict the need for emergency surgery (Fig. 1) with sensitivity of 94%, specificity of 74%, positive predictive value of 91% and negative predictive value of 81%.

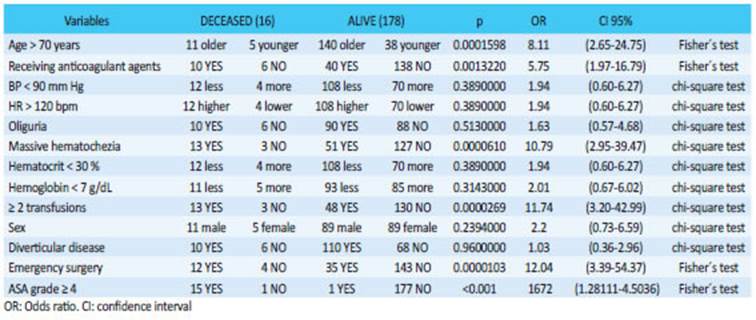

The AUC-ROC was 0.895295%, CI: 0.8476- 0.9428 (Fig. 2). Sixteen patients with severe LGIB died (8%); the variables significantly associated with mortality were age >70 years, anticoagulant therapy, massive hematochezia, requirement of two transfusions or greater and emergency surgery (Table 4). Fifteen of the sixteen patients who underwent surgery and died had ASA ≥ grade 4.

Discussion

Several classification tools have been developed to predict the severity and adverse outcomes in LGIB. In the United States, a classification tool called BLEED was developed, based on five variables (active bleeding, hypotension, coagulopathy, erratic mental status and comorbidities), for clinical use in patients admitted with either acute upper or lower gastrointestinal bleedings to predict the severity of the episode10.

This classification is simple and safe. Patients classified as high-risk had significantly greater rates of in-hospital complications, new episodes of bleeding and ICU hospitalizations10. Other authors have tried to validate the BLEED tool, obtaining good results in UGIB and a lower performance in LGIB than the one reported in previous publications3,11,12.

Strate et al. analyzed 24 variables in 252 patients. Hemodynamic instability, profuse hematochezia, syncope, nontender abdominal examination, associated comorbidities and anticoagulation obtained significant values1. They found that 84% of patients with more than 3 risk factors, 43% with 1 to 3 risk factors, and 9% with no risk factors experienced severe LGIB. This tool was subsequently validated and the results were similar in the derivation and validation cohorts (AUC-ROC: 0.761 and 0.754, respectively)2.

The clinical guidelines of the American College of Gastroenterology endorse these criteria and add age > 60 years, ongoing bleeding, a history of diverticular disease or angioectasia, elevated creatinine and anemia as factors related with severe episodes14. Other authors also consider the use of aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, hematocrit < 35% and gross blood per rectum as factors associated with severe LGIB3,11,13.

The Oakland score was developed In the Netherlands after analyzing 7 variables on a sample of 38 067 patients with LGIB15. The intention was to categorize patients into low or high risk. A score threshold of ≤ 8 points identified patients with minor LGIB who had 95% probability of safe discharge from the emergency department. Safe discharge is defined as absence of new episodes of bleeding, transfusion, interventions and death, continuing with outpatient management15,16. Patients with scores > 8 points should be hospitalized and the risk of complications increases. The score has a good performance to identify low-risk patients, while other classifications15-17 are better to identify high-risk patients. In Japan, a risk scoring system called NOBLADS was developed and validated to determine the clinical risk of LGIB using eight variables, which included history and clinical and laboratory tests18. The authors emphasize the importance of evaluating comorbidities, medication use, symptoms on presentation and hemodynamic and laboratory parameters in the first bleeding episode18.

This score discriminated patients with severe LGIB and might be used it in decision making regarding intervention and management in emergency settings18. Tapaskkar et al. compared the ability of seven validated clinical scores to predict severe LGIB (Strate, NOBLADS, Sengupta, Oakland, Blatchford, AIMS65, and Charlson Comorbidity Index)17. In their experience, albumin and hemoglobin levels were significant predictors of severe bleeding17. The Oakland score had the best performance to predict severe bleeding17. The accuracy of the CURE Hemostasis prognosis score, Charlston index and ASA score to predict severe LGIB was also evaluated. None of these tools showed a predictive accuracy > 70%, so their routine use is not recommended22.

The validity of the Strate and BLEED scores in clinical practice was also questioned. A total of 132 patients with LGIB (severe in 36% of cases) were identified and the performance of Strate and BLEED scores to predict outcomes was compared. The authors did not find a significant association in the results and concluded that Strate and BLEED scores were poor predictors of severity.26

When we compare the variables analyzed and the results of our series with those of international publications, we find a significant correlation with few differences. The same variables used in our series and in other studies only differed in the cutoff values, and our values were stricter. In our series, need for transfusions and parameters of hemodynamic instability were the variables with the strongest statistical power. There are differences with other variables. Age is not significantly different in some series while other studies consider this variable is a determining factor1,2,13,18,19. and becomes a relevant factor when it is accompanied by other factors.

Probably the result of our study (age > 70 years, p-value 0.000, odds ratio 2.55) is biased due to the characteristics of our institution where mean patient age is 72 years. The previous use of anticoagulants is another controversial aspect. Although the results are contradictory, several recent studies with good methodological quality support this association3,13,18.

Anticoagulation was not identified as a significant risk factor in our series. Comorbidities represent another aspect to consider with a significant effect on the results2,10,13,16,18,19. We consider that a history of previous diseases or their decompensation does not change the natural history of bleeding in terms of its magnitude and, therefore, does not modify the severity of the episode. For this reason, we did not include them in this analysis. There is a paucity of information on the factors associated with the need for emergency surgery. For most authors, hemodynamic instability, syncope, severe hematochezia, low hemoglobin, and transfusion requirement are strong predictors of emergency surgery1,2,9,21.

Chronic use of aspirin associated with a history of diverticular disease or angioectasia increases the risk of emergency surgery9,13. In the presence of severe associated comorbidities, it is considered a determining factor for intervention3,4,5,8,13,18,21.

Other authors reported that failed hemostasis through colonoscopy or arteriography is strongly related with the probability of emergency surgery4,6,14,23. BLEED score indicates that the higher the risk, the greater the need for emergency surgery10,20. The NOBLADS score reliably identifies patients at risk of requiring either endoscopic or surgical intervention18. When Camus et al. compared the ASA score, Charlson comorbidity index and CURE Hemostasis prognosis score, they found that each score had < 70% of accuracy for the prediction of emergency surgery, and concluded that “none of these scores had high enough accuracy (< 70%) to be recommended for routine clinical application”22. The significant variables in our series are described in Table 2. Using those variables without collinearity, we established a logistic regression analysis with the outcome “emergency surgery”. The model run with the variables BP < 90 mm Hg and massive hematochezia showed the best explanatory results. These results were used to construct a formula to predict the need for emergency surgery in patients with severe LGIB; goodness of fit was tested. Based on the values assigned to each variable, this formula would allow predicting surgery requirement within the first hours. The formula was very sensitive (94%), with a high positive predictive value (91%) and AUC-ROC of 0.895295%.

Comorbidities, a determining factor for many authors, do not represent a reliable prognostic index in clinical evaluation and the possible need for surgery for our group. Mortality in patients with severe LGIB is another outcome variable that remains controversial. Several reports have concluded that the statistically significant independent predictors of mortality are age (> 70 years), male sex, hemodynamic instability, copious bleeding, elevated creatinine levels, coagulopathies, intestinal ischemia, number of transfusions, bleeding in the context of other diseases, number of comorbidities and length of hospital stay1-3,8,9,13,15. Only Rios et al. mentioned emergency surgery as a determinant of mortality9. Another study evaluated 30-day mortality in patients readmitted for LGIB; the presence of comorbidities, bleeding in patients admitted for other clinical causes, and active cancer were the variables associated with the greatest risk31. The analysis comparing the ASA score, Charston comorbidity index and CURE Hemostasis prognosis score concluded that the ASA score was the best predictor of mortality (accuracy of 83.5%)22.

The ABC score evaluates 30-day mortality in patients with upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding, based on patients age, blood tests and comorbidities. In LGIB, patients with low (≤ 3), medium (4 to 7) and high (≥ 8) ABC scores had in-hospital mortality rates of 0.6%, 6.3% and 18%, respectively19. An analysis of 658 026 cases of LGIB with 1614 patients undergoing surgery identified age > 70 years, higher ASA class, open surgery, and total colectomy as risk factors of mortality21. As for mortality and type of surgery performed, Zeena Nackerdien and Swift reported a mortality rate of 12.2% in emergency total colectomies versus 1% in elective surgery31,32. They also found lower mortality in segmental resections and laparoscopic approach31,32. The association between comorbidities and mortality is another controversial aspect. For most specialists, mortality as a direct cause of bleeding is rare, and most deaths were caused by decompensation of previous diseases or surgical complications3-5,8,9,13,18,21.

These findings suggest that initial intensive care and management of comorbid conditions and other hospital outcomes are more likely to improve mortality rates in LGIB than potentially therapeutic early interventions9. We agree with this concept, and for this reason we consider that comorbidities should not be included in these studies. In our series ASA score (≥ grade 4), massive rectal bleeding, transfusions and emergency surgery were the strongest significant variables in terms of inhospital mortality. Interestingly, few authors include emergency surgery as a risk factor of mortality. In our series, mortality occurred in patients who underwent open total or subtotal colectomy. In a recent editorial, R, Kosowicz and L. Strate recommended that: “rather than developing numerous predictive models, future studies should focus on validating and refining the best of existing models”33. This was the spirit of our analysis: we gathered reliable, simple, available and internationally accepted variables, and added others based on our experience. To further strengthen the study, we added standardized, consecutive, and chronological data collection of patient care managed by a single group of surgeons following the same standards.

The retrospective design of this study, performed in a single institution, validated with our own sample and the lack of other variables that could improve the results constitute the weakness of this presentation.

Conclusions

Based on the results obtained in the present study, we can state that the variables analyzed are reliable and statistically significant to estimate the risk of severe bleeding, need for emergency surgery and mortality in lower gastrointestinal bleeding.

Although this is not the aim of this study, we consider that they can be reproduced in our setting and, they could be systematically used to classify patients after being validated by other centers to bring us closer to an ideal classification.

Referencias bibliográficas /References

1. Strate L, Orav EJ, Syngal S. Early predictors of severity in acute lower intestinal tract bleeding. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:838- 43. [ Links ]

2. Strate L, Saltzman JR, Ookubo R, Mutinga ML, Syngal S. Validation of a clinical prediction rule for severe acute lower intestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1821-7. [ Links ]

3. Newman J, Fitzgerald JE, Gupta S, et al. Outcome predictors in acute surgical admissions for lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:1020-6. [ Links ]

4. Latif J, Minetti M. Hemorragia digestiva baja grave. En: Gil O. Programa de actualización en cirugía (PROACI). Buenos Aires: Editorial Médica Panamericana; 2013. pp. 33-86. [ Links ]

5. Latif J. Hemorragia digestiva baja grave. En: Latif J, Rodríguez Martín J, Hequera J. Urgencias en las enfermedades del colon recto y ano. Buenos Aires: Akadia; 2011. pp. 229-46. [ Links ]

6. Latif J, Rodríguez Mendoza JV. Hemorragia digestiva baja grave. En: Latif J y cols. Manual de urgencias en coloproctología. Guías de práctica clínica de la Asociación Latinoamericana de Coloproctología. Buenos Aires: Akadia; 2019. pp. 313-34. [ Links ]

7. Latif J, Santamaría Valle M. Hemorragia digestiva baja. En: Blanco E y cols. Enfermedades del colon recto y ano. Coloproctología: enfoque clínico y quirúrgico. Buenos Aires: Amolca; 2013. pp.1968-86. [ Links ]

8. Strate L, Ayanian JZ, Kotler G, Syngal S. Risk factors for mortality in lower intestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008; 6:1004-10. [ Links ]

9. Ríos A, Montoya MJ, Rodríguez JM, et al. Severe acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding: risk factors for morbidity and mortality. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2007; 392:165-71. [ Links ]

10. Kollef MH, O’Brien JD, Zuckerman GR, Shannon W. BLEED: a classification tool to predict outcomes in patients with acute upper and lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:1125-32. [ Links ]

11. Zukerman G. Acute gastrointestinal bleeding: clinical essentials for the initial evaluation and risk assessment by the primary care physician. JAOA. 2000;10:54-7. [ Links ]

12. Huchchannavar S, Puttannavar G, Hebsur N. BLEED: a classification tool to predict outcomes in patients with upper and lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Int Surg J. 2017; 4:2683-8. [ Links ]

13. Velayos F, Sousa K, Lung E, et al. Early predictors of severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding and adverse outcomes: a prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:485-90. [ Links ]

14. Strate L, Gralnek IM. ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Patients with Acute Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:459-74. [ Links ]

15. Oakland K, Guy R, Uberoi R, et al, on behalf of the UK Lower GI Bleeding Collaborative. Acute lower GI bleeding in the UK: patient characteristics, interventions and outcomes in the first nationwide audit. Gut 2017;67:654-62. [ Links ]

16. Oakland K, Kothiwale S, Forehand T, et al. External Validation of the Oakland Score to Assess Safe Hospital Discharge Among Adult Patients With Acute Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e209630. Disponible en: National Center Of Biotechnology Information NCBI. Consultado el 22 de septiembre de 2021. [ Links ]

17. Tapaskar N, Blake A, Mei Steve, Sengupta Neil. Comparison of clinical prediction tools and identification of risk factors for adverse outcomes in acute lower GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89:1005-13. [ Links ]

18. Aoki T, Nagata N, Shimbo T, Niikura R, Sakurai T, Moriyasu S, et al. Development and Validation of a Risk Scoring System for Severe Acute Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016; 14:1562-70. [ Links ]

19. Laursen SB, Oakland K, Laine L, et al. ABC score: a new risk score that accurately predicts mortality in acute upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding: an international multicentre study. Gut. 2021; 70:707-16. [ Links ]

20. Valkhoff V, Miriam M, Kuipers E. Risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding associated with low-dose aspirin. Best Pract Res Cl Ga. 2012; 26:125-40. [ Links ]

21. Sue-Chue-Lam C, Castelo M, Baxter NN. Factors Associated with Mortality after Emergency Colectomy for Acute Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding. JAMA Surg. 2019;155:165-7. [ Links ]

22. Camus M, Jensen DM, Ohning GV, et al. Comparison of Three Risk Scores to Predict Outcomes of Severe Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016; 50:52-8. [ Links ]

23. Latif J, Leiro F, Rodríguez Martín J y cols. Hemorragias Digestivas Bajas. Sociedad Iberoamericana de Información Científica (S.I.I.C.). Salud y Ciencia. 2000;9:9-10. [ Links ]

24. Kaplan R, Heckbert S, Psaty B. Risk Factors for Hospitalized Upper or Lower Gastrointestinal Tract Bleeding in Treated Hypertensives. Prev Med. 2002; 34:455-62. [ Links ]

25. Frisancho Velarde O. Hemorragia digestiva baja. Acta Médica Per. 2006;23:174-9. [ Links ]

26. Xavier SA, Machado FJ, Magalhães JT, Cotter JB. Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding: are STRATE and BLEED scores valid in clinical practice? Colorectal Dis. 2019;21:357-64. [ Links ]

27. Li G, Ren J, Wang G, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding in Crohn disease. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:804. [ Links ]

28. Latif J. Relato Oficial: “Hemorragia Digestiva Baja Grave”. Sociedad Argentina de Coloproctología. Rev Argent Coloproct. 2007;18:387- 480. [ Links ]

29. Latif J, Leiro F y cols. Hemorragia Digestiva Baja Grave. Rev Argent Coloproctol. 1998;9:123-7. [ Links ]

30. Sengupta N, Tapper EB, Patwardhan VR, et al. Risk Factors for Adverse Outcomes in Patients Hospitalized with Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015; 90:1021-9. [ Links ]

31. Zeena Nackerdien D. Emergency Surgery for Lower GI Bleeding: What Is the Risk for Death? Disponible en: Med Page Today. Consultado el 3 de diciembre de 2020. [ Links ]

32. Swift D. Emergency Colectomy for Lower GI Bleeding: Death Risk Quantified. Hope is to “better equip surgeons to provide goalconcordant care”. Nov 2019.En: https://www.medpagetoday.com/gastroenterology/generalgastroenterology/83378 [ Links ]

33. Kosowicz RL, Strate L. Predicting outcomes in lower gastrointestinal bleeding: more work ahead. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019; 89:1014- 6. [ Links ]

Received: February 10, 2022; Accepted: August 15, 2022

texto en

texto en