Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista argentina de cirugía

versión impresa ISSN 2250-639Xversión On-line ISSN 2250-639X

Rev. argent. cir. vol.115 no.1 Cap. Fed. mayo 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.25132/raac.v115.n1.1683

Articles

Mixed circumferential hemorrhoidal prolapse. Combined treatment with mechanical stapler and laser coagulation

1 Unidad de Patología Orificial, Servicio de Cirugía General, Hospital Universitario CEMIC, Buenos Aires, Argentina

2 Servicio de Cirugía General. Hospital Universitario CEMIC, Buenos Aires, Argentina .

Introduction

Hemorrhoids are a very common anorectal condition and a prevalent health problem worldwide1. Several studies have reported that almost half of the general population will present symptoms associated with this disease by the age of 502, which can have a major impact on patients’ quality of life3.

There is still lack of consensus on the best treatment for hemorrhoids grade III and IV. Although conventional surgery is an option and has the benefit of solving the external and internal components when present4, it may be associated with pain and later return to normal activities3.

For this reason, several less invasive techniques have been described, including rubber band ligation for grades II-III internal hemorrhoids5, stapled haemorrhoidopexy6 and Doppler-guided hemorrhoidal artery ligation7, among others. However, none of these techniques are completely effective for treating external hemorrhoids, and excision of the external component must be added to complete the procedure. Although this prevents postoperative symptomatic recurrences, it also leads to more postoperative complications and pain, which is ultimately the same concern for surgeons regarding conventional hemorrhoidectomy.

For all these reasons, the aim of this publication is to describe a novel technique to treat advanced hemorrhoidal prolapse with external component combining stapled hemorrhoidopexy with laser coagulation of all the external hemorrhoids. The experience of the group, previously published, included 25 patients with grade III hemorrhoids with circumferential involvement associated with external disease.

Surgical technique

1. Treatment of the internal component-Stapled hemorrhoidopexy

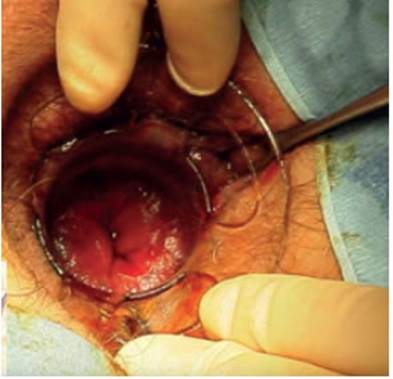

a- Inspection and anoscopy. Pudendal nerves block (Fig. 1)

FIGURE 1 Circumferential hemorrhoidal prolapse (left) and mechanical stapler device for procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids (PPH), PPH anoscope, fenestrated rectoscope and crochet hook (right)

Perform adequate examination of the region to determine grade and level of involvement of hemorrhoidal disease before requesting the opening of the mechanical stapler. With the patient under general anesthesia, hemorrhoids grade may be lower or the disease may be less severe; in this case, suture ligation is possible. Pudendal nerves are blocked with duracaine 0.5% plus lidocaine 2%.

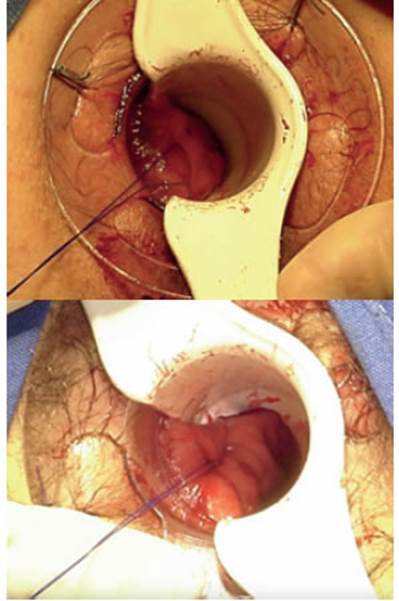

b- Insertion of fenestrated rectoscope and fixation to skin (Fig. 2)

FIGURE 2 The fenestrated rectoscope is inserted ensuring it remains above the pectine line and is fixated in four quadrants with silk or Vicryl-0 suture.

This step is crucial to correctly perform the entire procedure; it is a critical step to fix the anoscope once it is above the pectine line. The use of the dilator is recommended to progressively advance over the anal canal and fix the device when we are sure that it is correctly fixed. We use thick silk stitches to prevent it from moving out of the anal canal during the procedure.

c- Creation of a circumferential purse string (Fig. 3)

FIGURE 3 A circumferential purse string with polipropilene suture (type Prolene® 2-0) is created 3 -4 cm above the pectine line, starting at the 9 o’clock position and including the entire anal circumference.

The purse string is performed with polipropilene suture (type Prolene® 2-0). The following important technical aspects of this step should be considered: the purse string should be made using the pectine line as a reference (the importance of the correct positioning of the anoscope above the pectine line has been previously emphasized), starting 2 to 3 cm above it; this prevents postoperative pain (secondary to suturing part of the pectine line, which, unlike the rectal mucosa, has sensitive receptors) and the possible complications of sectioning part of the anal sphincter in case of performing it more distally. At the same time, a more proximal purse string is associated with higher risk of rectal stricture with an hourglass pattern, thus reducing the efficacy of the procedure. The stitches should be placed at the same level around the entire circumference; this is especially important in the posterior aspect, where the stitches tend to be displaced distally.

d- Device placement and tightening of the purse string (Fig. 4)

Once the device has been inserted, tighten the purse string and then proceed with closure until the safety level (in green in the device) is reached. Previously, the crochet hook must be used to slide the end of the thread through a port at the side of the device, as shown in the figure. Alternatively, while the surgeon creates the purse string, when he/she reaches the contralateral side a thread can be placed, fixed with the purse string, which can then be slipped using the crochet hook through a port on the right side of the mechanical stapler, and thus, in the next step, obtain the same tension on both sides. In women, consider pulling the vagina upward with a finger or using a surgical clamp, to avoid involving the vagina when closing the device.

e- Firing

As it can be appreciated in the figure 5, the device must be fired by exerting traction towards the caudal side of the thread used for creating the purse string (after being tightened). Thus, the suture is fired with one hand while the other hand is used to pull the thread (as a trigger). The device is then opened (2 turns are sufficient) and removed.

f- Staple line examination and hemostasis (Fig. 5)

Before removing the anoscope, check the stapler line to make sure it occupies the entire circumference. The 4 quadrants should be checked again in search of possible bleeding sites, using a regular anoscope or the anoscope of the device. If bleeding sites are found, suture with absorbable X-shaped stitches is usually effective to control bleeding. Checking the characteristics of the resected tissue is of utmost importance. It should be roundshaped and have uniform thickness all around the circumference.

2. Treatment of the external component

a- Identification and catheterization of external hemorrhoids with Abbocath® (Fig. 6)

After the external hemorrhoid requiring treatment has been identified, an Abbocath® is placed (instead of using the laser fiber directly on the hemorrhoid) to avoid thermal injury of the skin which can cause postoperative pain and, therefore, affect the final result of the surgery.

b- Laser coagulation of the external component (Fig. 7).

FIGURE 7 Progression of the fiber through the Abbocath® and laser coagulation of external hemorrhoids

The laser fiber connected to a diode with a wavelength of 1470 nm at a power of 7 watts in continuous mode is passed through the Abbocath® and into the lumen of hemorrhoid to selectively coagulate the tissue involving the submucosa, until the surgeon confirms that the tissue has shrunk. This procedure is repeated for each external plexus.

Discussion

The first results have already been published and have been favorable in terms of morbidity, postoperative quality of life and patient satisfaction index. Of a total of 25 patients who underwent this technique, only one complication (4%) was described, corresponding to a patient who required reoperation due to bleeding two weeks after hospital discharge. The staple line was explored under anesthesia but we did not find active bleeding and he was discharged 48 hours later. Pain was evaluated using a visual analogue scale during the immediate postoperative period; the median score was 5.28 points (SD: 2,25) and was adequately managed at home with scheduled analgesia and rescue medication. After the first week, the score dropped to 4.08 (SD: 2.48), and most patients were free from pain at one month after the procedure. Pain, prolapse and bleeding were considered preoperatively and postoperatively, with statistically significant improvements (P 0.001).

The SF-36 questionnaire was used, with significant improvements in patients’ self-perception of their quality of life. When patients were asked about the level of satisfaction with the procedure, 84% (21/25) responded they were very satisfied, 8% (2/25) were satisfied, 4% (1/25) were not very satisfied and another 4% (1/25) were not satisfied. Twenty-three patients (92%) would recommend the procedure. There were no short-term recurrencies8.

To date, none of the surgical procedures available have achieved all these objectives since the new alternatives for internal prolapse do not treat the external components when they are present.

Although we understand that the costs associated with this procedure are higher than those of conventional surgery, future studies should focus on comparing these costs, also including the postoperative time required to return to normal activities, which can be very long after conventional treatment of advanced hemorrhoidal disease3.

Referencias bibliográficas /References

1. Lohsiriwat V. Hemorrhoids: From basic pathophysiology to clinical management. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(17): 2009-17. [ Links ]

2. Riss S, Weiser FA, Schwameis K, Riss T, Mittlböck M, Steiner G, et al. The prevalence of hemorrhoids in adults. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27(2):215-20. [ Links ]

3. Gallo G, Martellucci J, Sturiale A, Clerico G, Milito G, Marino F, et al. Consensus statement of the Italian Society of Colorectal Surgery (SICCR): Management and treatment of hemorrhoidal disease. Tech Coloproctol. 2020;24(2):145-64. [ Links ]

4. Reis Neto JA, Quilici FA, Cordeiro F, Reis Jünior JA. Open versus semi-open hemorrhoidectomy: A random trial. Int Surg. 1992;77 (2):84-90. [ Links ]

5. Barron J. Office ligation treatment of hemorrhoids. Dis Colon Rectum. 1963; 6:109-13. [ Links ]

6. Corman ML, Gravié JF, Hager T, Loudon MA, Mascagni D, Nyström PO, et al. Stapled haemorrhoidopexy: A consensus position paper by an international working party-indications, contra-indications and technique. Colorectal Dis. 2003;5(4):304-10. [ Links ]

7. Infantino A, Bellomo R, Dal Monte PP, Salafia C, Tagariello C, Tonizzo CA, et al. Transanal haemorrhoidal artery echodoppler ligation and anopexy (THD) is effective for II and III degree haemorrhoids: A prospective multicentric study. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12 (8):804- 9. [ Links ]

8. Piccinini P, Avellaneda N, Santillán M, et al. A new procedure for treatment of mixed circumferential hemorrhoidal prolapse combining stapled hemorrhoidopexy with laser intra-hemorrhoidal coagulation: Initial experience of a single surgeon and short-term results. Indian J of Colorectal Surg. 2020;3 (3):59-64. [ Links ]

Received: August 02, 2022; Accepted: September 05, 2022

texto en

texto en