Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista argentina de cirugía

versión impresa ISSN 2250-639Xversión On-line ISSN 2250-639X

Rev. argent. cir. vol.116 no.2 Cap. Fed. jun. 2024 Epub 01-Jun-2024

http://dx.doi.org/10.25132/raac.v116.n2.1773

Original article

Laparoscopic cephalic pancreaticoduodenectomy with laparoscopic vascular resection

1Sanatorio de la Trinidad Mitre, CABA. Argentina

2Centro Gallego de Buenos Aires, CABA. Argentina

3Hospital Zonal General de Agudos Mariano y Luciano de la Vega, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Background:

Cephalic pancreaticoduodenectomy (CPD) with venous resection is indicated for the treatment of ductal adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas, either through laparoscopy or laparotomy.

Objective:

The aim of this study was to describe the results of a series of patients undergoing CPD with venous vascular resection and compare morbidity and mortality between the laparoscopic approach and open surgery.

Material and methods:

We conducted a retrospective, comparative and observational study of patients who underwent CPD with venous vascular resection between January 2022 and July 2023. Criteria for laparoscopic surgery were age < 80 years, interface between tumor and vein of 180° of the circumference of the vessel wall or less on computed tomography, good performance status, and no previous neoadjuvant treatment.

Results:

A total of 23 CPD procedures with venous vascular resection were performed: 11 by laparoscopy and 12 by laparotomy. The 11 laparoscopic procedures were lateral resections, and in the 12 patients approached by laparotomy, 5 were total portal vein resections and 7 were lateral resections. Portal vein clamping time and need for transfusion was similar in both groups. The pathological examination reported R0 resections in 78.2% and venous invasion in 40.9%. The complications associated with laparoscopy and laparotomy were pancreatic fistula in 4 and 3 patients, respectively, delayed gastric emptying in 1 and 4 patients, respectively, biliary fistula in 1 and 0 patients, respectively, aspiration pneumonia i 1 and 1 patients, respectively and surgical site infection in 0 and 1 patients, respectively. Mortality was 8.6% (n =2), one in each group.

Conclusion:

According to the criteria used, the morbidity and mortality of CPD with vascular resection were similar for laparoscopy and laparotomy.

Keywords: laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy; laparoscopic vascular resection; minimally invasive pancreatic surgery; pancreatic cancer

Introduction

Laparoscopic cephalic pancreaticoduodenectomy (CPD) has been a controversial technique since its first publication due to its long and difficult learning curve. However, several prospective and randomized studies have demonstrated that it is a feasible method, with morbidity and mortality rates similar to those of conventional surgery when performed by surgeons specialized in pancreatic surgery and in high-complexity laparoscopic procedures1),(2,3,4),(5.

Once the learning curve has been overcome, more complex procedures can be performed. Vascular resection can be performed laparoscopically without increasing morbidity and mortality of open surgery6,7.

The aim of this study was to describe the results of a series of patients undergoing CPD with venous vascular resection and compare morbidity and mortality between the laparoscopic approach and open surgery.

Material and methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis of the data recorded in our database of patients who underwent CPD and required venous vascular resection between January 2022 and July 2023. We chose that short period because the first laparoscopic venous resection in CPD was performed in February 2022. All the procedures were performed by the same surgical team in private institutions (Sanatorio de la Trinidad Mitre, Trinidad Palermo, Centro Gallego de Buenos Aires) and in a public hospital (Hospital Mariano y Luciano de la Vega).

According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) classification, a tumor is considered resectable when the interface between tumor and vein is < 180° of the circumference of the vessel wall and borderline resectable when it is > 180°8.

Cephalic PD was indicated for malignant and pre-malignant tumors; the indication for venous resection was due to tumor invasion suitable for surgical resection either by laparotomy or laparoscopy. Laparoscopic venous resection was started after performing 110 laparoscopic CPD.

Patients with arterial invasion, distant metastases or ascites on imaging tests and those with poor performance status who could not undergo resection were excluded.

The decision to use a laparoscopic approach or laparotomy was based on the extent of venous invasion, patient performance status, and age. Criteria for laparoscopic CPD were age < 80 years, interface between tumor and vein of 180° of the circumference of the vessel wall or less on computed tomography, good performance status, and no previous neoadjuvant treatment.

Surgical technique

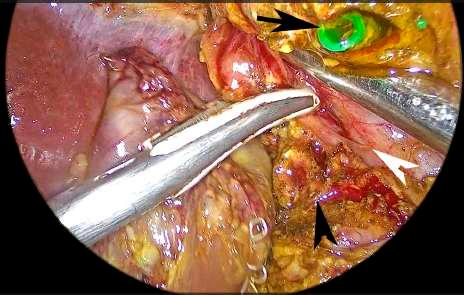

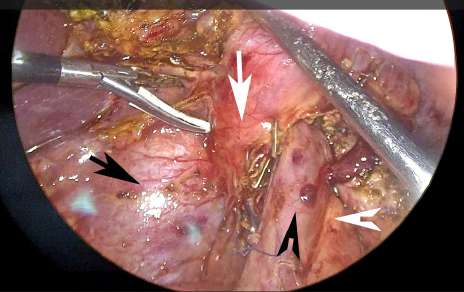

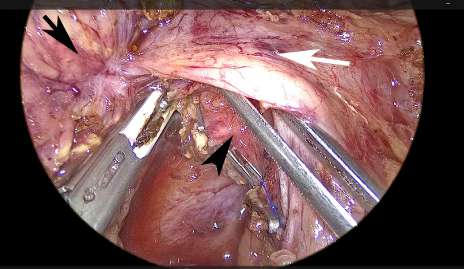

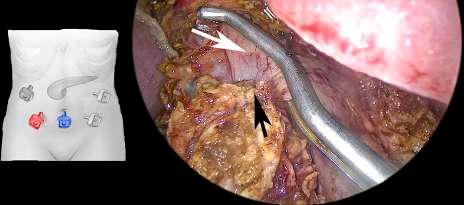

The standard technique of laparoscopic CPD that is used by our group has already been described in a previous article5. To perform the laparoscopic lateral resection of the portal vein, the entire uncinate process is dissected close to the superior mesenteric artery, leaving the section that is attached to the portal vein as the last surgical gesture. The section of the pancreas exposes the anterior aspect of the portal vein and its connection with the splenic vein. The bile duct is sectioned and all the tissue lateral to the suprapancreatic portal vein is dissected (Fig. 1). For this purpose, the optical trocar is placed in the right iliac fossa. The surgeon uses the trocars placed in the right hypochondriac region and umbilical region. This technique provides a lateral view of the portal vein, allowing for its dissection until the area affected by the tumor is reached. The wide Vautrin-Köcher maneuver involves pulling up the duodenum and head of the pancreas (Fig. 2) to perform the dissection and separate it from the superior mesenteric artery. This maneuver requires great care to avoid inadvertent injury to the portal vein. It is necessary to remove as much tissue as possible to minimize venous resection (Fig. 3). Once the posterior and anterior aspects of the pancreas have been released, a laparoscopic vascular clamp is placed to section the vein (Fig. 4). The vein is sectioned using scissors (Fig. 5) and repaired with continuous 5-0 polypropylene suture (Fig. 6). The vascular clamp is removed and the reconstruction phase begins.

FIGURE 1 Dissection of the right lateral border of the suprapancreatic portal vein. Section of the bile duct. Black arrowhead: pancreas. White arrowhead: portal vein. Black arrow: bile duct

FIGURE 2 Upward traction of the head of the pancreas and duodenum to release the posterior aspect of the portal vein and superior mesenteric vein. Black arrow: vena cava. Black arrowhead: portal vein. White arrow: pancreas. White arrowhead: superior mesenteric artery

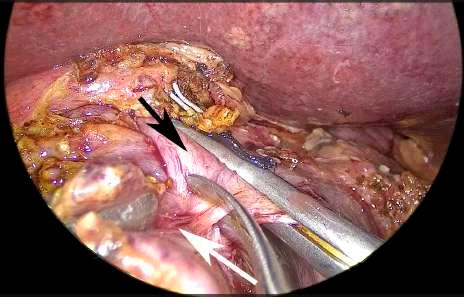

FIGURE 3 Dissection of the right lateral border of the superior mesenteric artery. The healthy tissue is freed until the area of venous invasion. Black arrow: tumor. Black arrowhead: superior mesenteric artery. White arrow: portal vein

FIGURE 4 A Satinsky vascular clamp is placed in the portal vein. The tumor is freed and is only in contact with the portal vein. In the diagram, the red trocar is used to introduce the scope and the blue trocar to introduce the vascular clamp. Black arrow: tumor. White arrow: portal vein

FIGURE 5 The portal vein is sectioned with scissors far from the area of tumor invasion. Black arrow: portal vein. White arrow: tumor

FIGURE 6 Portal vein repaired with continuous 5-0 polypropylene suture. The clamp is released. Black arrow: portal vein sutured

If portal vein involvement is extensive, a laparotomy is performed. After portal vein resection, a lateral peritoneal patch can be placed, or a complete resection of the vein can be performed and replaced with an expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) interposition graft. As with laparoscopic surgery, all steps of pancreaticoduodenectomy are completed except for the area of vascular invasion. In cases of extensive lateral resection of the portal vein, a peritoneal patch is placed. Once the portal vein has been completely resected, the splenic vein is ligated and sectioned. Vascular reconstruction is performed using an 8-mm ringed PTFE graft. It is not necessary to reinsert the splenic vein.

After surgery, all the patients were transferred to the intensive care unit and received prophylactic heparin. If no complications developed, the nasogastric tube was removed on postoperative day 1 and oral feeding was started.

The definitions of postoperative complications, as pancreatic fistula, delayed gastric emptying and bleeding were based on the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Complications were categorized using the Clavien-Dindo classification. Drains were removed in the absence of fluid output or biochemical fistula. The patients were discharged when they tolerated oral diet, were able to walk independently and had no clinical or biochemical signs of infection.

The pathological examination considered R0 resections as those with a margin > 1 mm. The percentages of R0 resections and invasion of venous layer intima were estimated.

The following variables were analyzed separately for those who underwent laparoscopic surgery and those who underwent laparotomy:

Intraoperative variables: operative time, portal vein clamping time and need for transfusion.

Postoperative variables: incidence of pancreatic fistula, delayed gastric emptying, biliary fistula, and overall morbidity and mortality.

Results

A total of 86 CPDs were performed during the study period; 45 were fully laparoscopic procedures and the rest were through laparotomy.

Twenty-three patients underwent venous resection: 12 through laparotomy and 11 through laparoscopy. The pathological examination reported ductal adenocarcinoma in 22 patients and neuroendocrine tumor in 1.

Mean age was 72 years (range 54-92). The demographic and tumor characteristics by type of approach are described in Table 1.

TABLE 1 Demographic and tumor characteristics

| Variables | Laparoscopic approach n = 11 | Conventional approach n = 12 |

|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 8 (72%) | 5 (41%) |

| Age (years) mean | 69,8 | 74 |

| Conversion | 2 | Not applicable |

| Resectable tumors | 11 | 5 |

| Borderline tumor | 0 | 7 |

| Tumor size (cm) | 3.27 | 3.75 |

The 11 patients approached laparoscopically underwent lateral portal vein resection. In 9, the resection was fully laparoscopically. One patient required conversion to open surgery via an 8-cm mini-incision because the procedure was difficult to complete. Another patient required conversion via a mini-incision to perform a lateral resection of the vena cava after the lateral resection and reconstruction of the portal vein were completed.

In patients intervened through laparotomy, 3 patients underwent total portal vein resection. The reconstruction techniques used were placement of an 8-mm ringed PTFE graft or a lateral peritoneal patch or an end-to-end anastomosis between the portal vein and superior mesenteric vein. The rest of the patients underwent lateral portal vein resection.

Mean operative time was 445 minutes (range 330-500 minutes) through laparoscopy and 331 minutes (range 200-420 minutes) through laparotomy.

Mean portal vein clamping time for lateral vein resection was 28 minutes (range 21-42 minutes) for laparoscopic surgery and 26 minutes (range 15-43 minutes) for laparotomy (including lateral and total resections).

The patients required an average of one unit of transfusion each (range 0-4 units per patient), 0.9 units per patient (range 0-3 units) for laparoscopic surgery and 1.1 units per patient (range 0-4 units) for laparotomy.

The pathological examination reported R0 resections in 18 cases (78.2%) and R1 resections in 5 patients, 3 through laparoscopy and 2 through laparotomy. Venous invasion was confirmed in 40.9% of the cases.

The complications in patients undergoing laparoscopy were pancreatic fistula (n = 4), biliary fistula (n = 1), delayed gastric emptying (n = 1) and bilateral pneumonia (n =1). Pancreatic fistulas were type A in 4 patients, type B in 1 patient who required percutaneous drainage and type C in 1 patient who was reoperated and presented fistula-related bleeding on postoperative day 10. Biliary fistula occurred in the same patient with type B pancreatic fistula.

The complications in patients undergoing laparotomy included type A pancreatic fistula (n = 3), delayed gastric emptying (n = 3), aspiration pneumonia (n =1) and surgical site infection (n = 2).

In the 23 patients undergoing vascular resection mortality was 8.69% (n = 2). One patient in the laparoscopy group presented bleeding associated with pancreatic fistula on postoperative day 10. The patient underwent re-exploration but died 32 days after surgery due to multiple organ failure.

Another 92-year-old female patient in the laparotomy group died of aspiration pneumonia 23 days after surgery after starting an oral diet.

Discussion

Cephalic PD is a widely accepted technique for ductal adenocarcinoma and locally advanced neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas8,9. The aim of PD with en bloc vein resection is to increase the number of patients with R0 resection and thus improve survival. According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) classification, a tumor is considered resectable when the interface between tumor and vein is < 180° of the circumference of the vessel wall and borderline resectable when it is > 180°. Venous resection can be lateral or total. Total venous resection is indicated when tumor contact with the vein is > 4 cm in the longitudinal direction or when the interface between the tumor and the portal vein is > 180° of the vessel wall circumference. In cases of lateral resection, the vein is repaired with continuous 5-0 polypropylene suture. However, in some situations, a lateral peritoneal or saphenous vein patch is placed to avoid significant reduction in portal vein diameter. There are 2 options for vein reconstruction after total portal vein resection. One option is to mobilize the tissues and perform a tension-free end-to-end venous anastomosis. The other possibility is to use a venous or vascular interposition graft to restore the venous blood flow to the liver. In these cases, the splenic vein is ligated and not reinserted in the graft used. This type of surgery should be performed in high-volume centers. Venous resection can be performed laparoscopically if the surgical team has extensive experience in laparoscopic CPD6,7. The publications on laparoscopic CPD with major vascular resection show that it is a feasible procedure with good results6,7.

A weakness of laparoscopic CPD is that it is a technically challenging procedure with a long learning curve (no longer than the learning curve for conventional CPD), which is difficult reproduce. Several prospective and randomized studies have demonstrated advantages of the laparoscopic approach over the conventional approach in terms of length of hospital stay and need for transfusion1),(2,3,4),(5. In addition, the R0/R1 index is similar to that of open surgery and the number of lymph nodes resected is not inferior or even higher11,12.

It is recommended that the learning curve be supervised by surgeons with extensive experience in conventional and laparoscopic pancreatic surgery. In our group, surgeons on the learning curve perform several steps of resection and reconstruction until they are able to reduce operative times, always in selected cases. Once experience is gained, more complex procedures are included. Another key factor in reducing the learning curve is the frequency with which laparoscopic CPD is performed. Performing this procedure on a weekly basis is likely to accelerate and improve the learning process compared to a monthly frequency. The repetition of the procedure every week allows for a more rapid incorporation of the technical steps of resection.

After performing at least 110 fully laparoscopic resections, the surgeon was deemed proficient in performing fully laparoscopic vascular resections. After 110 cases, the operative time for laparoscopic surgery was found to be no more than 2 hours longer than that of conventional surgery. This allowed for an increase in the complexity of cases undergoing fully laparoscopic venous resection. Based on our experience, the laparoscopic approach is approximately 110 minutes longer than the conventional approach. Venous resection requires the use of appropriate instruments and extensive experience in intracorporeal suturing. A Satinsky vascular clamp can be used for lateral resection of the portal vein. As shown in Figure 4, the vascular clamp is inserted through the umbilical trocar (in blue), which allows the clamp to be positioned parallel to the portal vein. The scope is introduced in the trocar placed in the right lumbar region (in red). The surgeon stands on the patient’s right side and operates through the trocars placed in the right hypochondriac region and left lumbar region. In 10 of the 11 patients, the portal vein was sutured through these trocars. In on patient, a 5-mm trocar had to be placed to introduce the clamp and suture the vein using the umbilical trocar.

The reasons for conversion were technical difficulties that prolonged resection time in one patient with morbid obesity and the need for vena cava resection due to tumor contact in the other. Bleeding was not the cause of conversion and in both cases portal vein resection and reconstruction was successfully completed. The laparoscopic approach did not result in any additional complications beyond those typically associated with conventional surgery.

The limitations of this study include its retrospective design and sample size, as well as the fact that it is an initial stage of vascular resections in our surgical group.

As our experience grows, we will be able to perform complete resections on borderline tumors. This will enable the design of a randomized trial to determine whether the minimally invasive approach for locally advanced disease is useful or not.

In conclusion, the morbidity and mortality of CPD with vascular resection were similar for laparoscopy and laparotomy following the criteria used to select the technique.

An extensive training in laparoscopic procedures allows to safely reproduce the majority of conventional procedures.

Referencias bibliográficas /References

1. Ausania F, Landi F, Martínez-Pérez A, Fondevila C. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing laparoscopic vs open pancreaticoduodenectomy. HPB (Oxford). 2019;21(12):1613-20. [ Links ]

2. Feng Q, Liao W, Xin W, Jin H, Du J, Cai Y, et al. Laparoscopic Pancreaticoduodenectomy versus Conventional Open Approach for Patients with Pancreatic Duct Adenocarcinoma: An Up-to-Date Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Oncol. 2021(11):749140.doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.749140. eCollection 2021. [ Links ]

3. Poves I, Burdi F, Morató O, Iglesias M, Radosevic A, Ilzarbe L, et al. Comparison of Perioperative Outcomes Between Laparoscopic and Open Approach for Pancreatoduodenectomy, The PADULAP Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Surg. 2018;268(5):731-9. [ Links ]

4. Palanivelu C, Senthilnathan P, Sabnis SC, Babu NS, Srivatsan Gurummurthy S, Anand Vijai N, et al. Randomized clinical trial oflaparoscopic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for periampullary tumors. Br J Surg. 2017;104(11):1443-50. [ Links ]

5. Uranga L, Kohan G, Bisio L, Ditulio OA, Monestés JO, Carbajal Maldonado AL y cols. Cien duodenopancreatectomías cefálicas laparoscópicas. Experiencia de dos grupos de trabajo. Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam. 2020;50(2):109-17. [ Links ]

6. Kendrick M, Sclabas G. Major venous resection during total laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy. HPB (Oxford). 2011;13(7):454-8. [ Links ]

7. Wang X, Cai Y, Zhao W, Gao P, Li Y, Liu X, et al. Laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy combined with portal-superior mesenteric vein resection and reconstruction with interposition graft: Case series. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019; 98(3): e14204. [ Links ]

8. Spencer Liles J, Katz MHG. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection for pancreatic head adenocarcinoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2014;14(8):919-29. [ Links ]

9. Fusai GK, Tamburrino D, Partelly S, Lykoudis P, Pipan P, Di Salvo F, et al. Portal vein resection during pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. An international multicenter comparative study. Surgery. 2021;169(5):1093-101. [ Links ]

10. Isaji S, Mizuno Y, Windsor J, Bassi C, Fernández-Del Castillo C, Hackert T, et al. International consensus on definition and criteria of borderline resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma 2017. Pancreatology. 2018;18(1):2-11. Doi: 10.1016/j.pan.20217.11.011. PMID: 29191513. [ Links ]

11. Adam MA, Choudhury K, Dinan MA, Reed SD, Scheri RP, Blazer DG, et al. Minimally invasive versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy for cancer: practice patterns and short-term outcomes among 7061 patients. Ann Surg. 2015;262:372-7. [ Links ]

12. de Rooij T, Lu MZ, Willemijn Steen M, Gerhards MF, Dijkgraaf MG, Busch OR, et al. Minimally Invasive versus Open Pancreatoduodenectomy: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Comparative Cohort and Registry Studies. Ann Surg. 2016; 264:257-67. [ Links ]

Received: October 02, 2023; Accepted: March 21, 2024

texto en

texto en