Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista argentina de cirugía

versión impresa ISSN 2250-639Xversión On-line ISSN 2250-639X

Rev. argent. cir. vol.116 no.1 Cap. Fed. mar. 2024 Epub 26-Feb-2024

http://dx.doi.org/10.25132/raac.v116.n1.1746

Original article

Pancreatic resections for metastases in the pancreas: analysis of surgical and oncologic outcomes. A retrospective cohort study

1Servicio de Cirugía General del Hospital J. B. Iturraspe, Ciudad de Santa Fe, Argentina.

2Grupo MIT, Ciudad de Santa Fe. Argentina.

3Servicio de Cirugía General, Sanatorio Santa Fe. Argentina

Background:

Pancreatic metastases are rare but are likely to be diagnosed more frequently in the future due to the increase in oncology surveillance programs.

Objective:

The aim of this study was to describe the surgical and oncologic outcomes of a series of patients undergoing surgery for pancreatic metastases.

Materials and methods:

We conducted a retrospective, descriptive, and multicenter cohort study on patients who underwent pancreatic resections for metastases in the pancreas by the same surgical group between January 2016 and December 2022 in three healthcare providers.

Results:

A total of 19 patients were operated on, mean age was 59 years (45-79), and 11 were women with good performance status and no other evidence of oncologic disease. Clear cell renal cell carcinoma was the primary tumor in 14 cases (7 diagnosed during surveillance), and the remaining primary tumors were one case of breast ductal carcinoma, one testicular cancer, one colorectal cancer, one melanoma and one cervical cancer. The surgical techniques used were pancreatectomies and splenectomies in 7 patients (5 via laparoscopy and 2 conventional procedures), 4 enucleations (3 conventional procedures and 1 laparoscopic surgery), 3 conventional cephalic pancreaticoduodenectomies, 2 conventional central pancreatectomies and one spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy. No deaths were reported within 90 days of surgery, and overall survival and disease-free survival were 58 and 53 months, respectively.

Conclusion:

Resection of pancreatic metastases is safe and provides good oncologic outcomes and overall survival when performed with a multidisciplinary approach in centers with a high volume of hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgeries and in selected cases.

Keywords: pancreatic metastases; pancreatic resection; renal cell carcinoma.

Introduction

Pancreatic metastases are rare but are likely to be diagnosed more frequently in the future due to the increase in oncology surveillance programs1,2.

Isolated pancreatic metastases are usually from renal cell carcinoma, while other primary tumors include colorectal cancer, melanoma, breast cancer, lung cancer and sarcoma. Nowadays, surgeons have a wide range of options when deciding how to approach pancreatic metastases. Metastasectomy is the cornerstone for increasing overall survival, and a multidisciplinary approach is essential1,3,4,5,6,7.

The aim of this study was to describe the surgical and oncologic outcomes in patients undergoing resection of pancreatic metastases in three highvolume centers in the city of Santa Fe.

Material and methods

We conducted a retrospective, descriptive, and multicenter cohort study on patients who underwent pancreatic resections for metastases, perfomed by the same surgical group, between January 2016 and December 2022 in three healthcare providers: one public (Hospital J. B. Iturraspe) and two private centers (MIT Group and Sanatorio Santa Fe). The clinical data, results of imaging tests, surgical techniques, pathology reports and follow-up data were collected from medical records and direct interrogation. All the information was recorded in a Microsoft Excel® spreadsheet. Patients with isolated pancreatic metastases and a controlled primary tumor without evidence of recurrence were selected.

Results

During the period described, 19 patients underwent pancreatic resections for pancreatic metastatic disease. All patients were operated with curative intent. Mean age was 59.4 years, median age was 62 years (45-79), and 11 patients were women.

Clear cell renal cell carcinoma was the primary tumor in 14 cases (Fig. 1). The remaining primary tumors were one case of breast ductal carcinoma, one seminoma, one colorectal cancer (adenocarcinoma), one skin cancer (melanoma) and one cervical cancer. On seven occasions, the diagnosis of pancreatic metastases was made during surveillance of patients treated for renal cancer. In patients with symptoms, 9 presented with abdominal pain, one with jaundice, one with low gastrointestinal bleeding and one with weight loss. Median disease-free interval from diagnosis of the primary tumor to diagnosis of metastasis was 70.78 months (12-179). Ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) scan were used in all the cases. In 4 patients, the ultrasound did not show abnormal findings, but in all the patients the CT scan documented and characterized the metastases.

FIGURE 1 Histological section of pancreatic parenchyma with metastases of clear cells renal cell carcinoma showing chromophobe areas of renal cell carcinoma

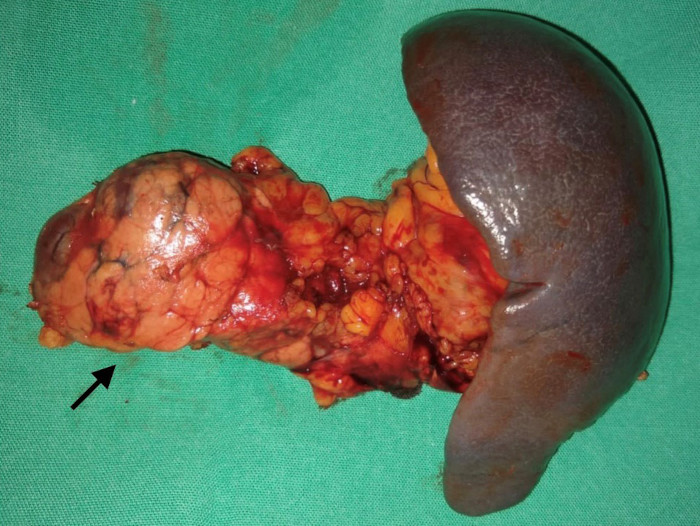

The following surgical techniques were used: pancreatectomies and splenectomies in 7 patients (5 via laparoscopy and 2 conventional procedures) (Fig. 2), 4 enucleations (3 conventional procedures and 1 laparoscopic surgery), 3 conventional cephalic pancreaticoduodenectomies, 2 conventional central pancreatectomies and one spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy.

FIGURE 2 Surgical specimen of laparosopic pancreatectomy and splenectomy; the arrow shows the lesion to resect

The approach chosen was often influenced by the equipment available and health insurance coverage, particularly in the private sector. We always aimed to preserve as much parenchyma as possible, and all extensive resections were confirmed as R0 according to the pathology report.

Complications were categorized according to the Clavien-Dindo classification3 and grouped with the surgical techniques, as presented in Table 1. Of the 19 patients operated on, 4 developed one complication requiring major intervention. There was no operative mortality, defined as deaths within 90 days of surgery, in this series. Of the 19 patients, 5 experienced disease recurrence (4 cases of local recurrence and 1 case of distant recurrence). The primary tumors were breast cancer (ductal carcinoma), testicular cancer (seminoma), renal cancer (clear cell carcinoma), colorectal cancer (adenocarcinoma), and uterine cancer (cervical carcinoma). By the end of the observation, mean overall survival was 58.61 months, and mean disease-free survival was 53.46 months.

Table 2 shows overall survival for each tumor.

TABLE 1 Complications according to the Clavien-Dindo classification and surgical technique

| Complicaciones | CD0 | CDI | CDII | CDIII A | CDIII B | CDIV A | CDIV B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Menores | Mayores | ||||||

| Technique | |||||||

| CPD | 1 | 1 | |||||

| TOD | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Distal pancreatectomy | |||||||

| Central pancreatectomy | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Enucleation | 1 | ||||||

CPD: cephalic pancreaticoduodenectomy; TPD: total pancreaticoduodenectomy.

TABLE 2 Median overall survival by primary tumor

| Primary tumor | Time in months |

|---|---|

| colorectal cancer (adenocarcinoma) | 12 (3-22) |

| Breast cancer (ductal carcinoma) | 23 (11-47) |

| Testicular cancer (seminoma) | 32 (3-68) |

| Uterine cancer (cervical carcinoma) | 32 (4-56) |

| Skin cancer (melanoma) | 33 (7-54) |

| Renal cancer (clear cell carcinoma) | 91 (61-111) |

Discussion

In Argentina, pancreatic metastases represent 0.25% and 5% of all pancreatic tumors6. The primary tumor that most commonly metastasizes to the pancreas is renal cell carcinoma5, as in our sample. Metastases can be synchronous or metachronous.

The main hypothesis explaining how the primary tumor metastasizes to the pancreas is tumor angiogenesis. Different micro.RNAs, especially mRNA-30a, have been shown to be involved in tumor progression and metastasis in renal cancer and other cancers, and are independent predictors of hematogenous spread of renal cell carcinoma. Fox proteins have also been described as signaling pathways that could play a critical role in renal cancer dissemination5,8.

Most pancreatic metastases are asymptomatic, but some may present with jaundice and abdominal pain4,6,7. In our sample, 9 patients presented with abdominal pain, one with jaundice, one with low gastrointestinal bleeding and one with weight loss.

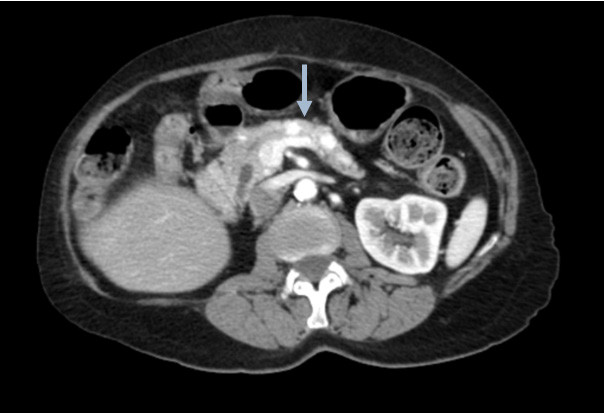

Among imaging tests, ultrasound can identify pancreatic lesions, while magnetic resonance imaging provides more detailed assessment. Computed tomography scan is crucial in preoperative decision making as it can rule out locoregional and distant disease (Fig. 3). Metastases of renal cell carcinoma typically appear as lesions with increased uptake during the arterial phase10. Other tests, such as positron emission tomography (PET), can be used to assess disease extent if extrapancreatic dissemination is suspected4,6. In our experience, all our patients underwent CT scanning, which was essential for identifying and characterizing metastatic lesions. Due to availability and costs, PET was not placed in the same hierarchy.

FIGURE 3 Computed tomography scan at the level of the pancreatic body, showing two well-delineated hypervascular nodular lesions measuring 8 mm and 10 mm in diameter that become isodense with the rest of parenchyma in portal vein/delayed phases. An ectasia of the main pancreatic duct, with a diameter of 4 mm, is identified between both lesions.

The type of primary tumor is the most important prognostic factor associated with survival after surgery for metastasis to the pancreas. Renal cell carcinoma (Table 2) has the best prognosis after resection, with an overall survival of 91 months, but there are significant differences in survival rates compared to other types of tumors. In our sample, clear cell renal cell carcinoma was the primary tumor in 14 cases.

Other risk factors, independent of the primary tumor, include symptomatic lesions at diagnosis and a shorter disease-free interval before metastases develop.

Cases of renal cell carcinoma may have a disease-free interval of more than 10 years, which highlights the importance of long-term surveillance.

In a recent review by Casajoana and Fabregat, of 321 patients with pancreatic metastases of renal origin treated at Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge, current survival and disease-free survival at 5 years were 72.6% and 57%, respectively10, similar to the series presented here.

As Untch and Allen have demonstrated in their experience at Memorial Sloan-Kettering, the goal of pancreatic metastasectomy should be to resect the lesion in a way that spares the most pancreatic parenchyma, as even limited resections of the pancreas can precipitate diabetes mellitus. Thus, enucleation should be considered when feasible7. In fact, they also recommend an intraoperative ultrasound scan to help guide the resection6,7,8,9.

Identifying and developing prognostic biomarkers is an important next step for managing these patients. Patients with an aggressive disease genotype may avoid the morbidity of a pancreatectomy and receive systemic therapies. Other patients with a favorable prognosis may avoid chemotherapy and be

In conclusion, this experience confirms that resection of pancreatic metastases is safe and provides good oncologic outcomes and overall survival when performed with a multidisciplinary approach in centers with a high volume of hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgeries and in selected cases.

Referencias bibliográficas /References

1. Sperti C, Moletta L, Patanè G. Metastatic tumors to the pancreas: The role of surgery. World J Gastrointest Oncol [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2023 Aug 2];6(10):381-92. Available from: Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v6.i10.381 . [ Links ]

2. Gutiérrez Troncoso ML. Análisis de la heterogeneidad genética del adenocarcinoma ductal de páncreas y su relación con las características de la enfermedad. Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca; 2019. [ Links ]

3. Etcheverry MG, Pierini L, Ruiz G, Aguilar F, Pierini ÁL. Metachronous pancreatic metastasis of renal carcinoma: report of 4 cases. Rev Argent Cirug [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2023 Aug 2];108(3):130-3. Available from: Available from: https://revista.aac.org.ar/index. php/RevArgentCirug/article/view/239 [ Links ]

4. Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience: Five-year experience. Ann Surg [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2023 Aug 2];250(2):187-96. Available from: Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19638912/ [ Links ]

5. Pan B, Lee Y, Rodríguez T, Lee J, Saif MW. Secondary tumors of the pancreas: a case series. Anticancer Res [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2023 Aug 2];32(4):1449-52. Available from: Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22493384/ [ Links ]

6. Rubio JS, Glinka J, Balmer M, Ditulio O, Mazza O, Capitanich P, et al. The pancreas as a target organ for metastases: Multi-center study in Argentina. MOJ Surg [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Aug 2];10(2):31-5. Available from: Available from: https://medcraveonline.com/MOJS/the-pancreas-asa-target-organ-for-metastases-multi-center-study-in-argentina.html [ Links ]

7. Untch BR, Allen PJ. Pancreatic metastasectomy: the Memorial Sloan-Kettering experience and a review of the literature: Pancreatic Metastasectomy. J Surg Oncol [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2023 Aug 2];109(1):28-30. Available from: Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/24122337/ [ Links ]

8. Reddy S, Wolfgang CL. The role of surgery in the management of isolated metastases to the pancreas. Lancet Oncol [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2023 Aug 2];10(3):287-93. Available from: Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19261257/ [ Links ]

9. Chin W, Cao L, Liu X, Ye Y, Liu Y, Yu J, et al. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma to the pancreas and subcutaneous tissue 10 years after radical nephrectomy: a case report. J Med Case Rep [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2023 Aug 2];14(1):36. Available from: Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32098617/ [ Links ]

10. Casajoana A, Fabregat J, Peláez N, Busquets J, Valls C, Leiva D y cols. Indicaciones y resultados de la resección de metástasis pancreáticas. Experiencia en el Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge. Cir Esp [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2023 Aug 2];90(8):495-500. Available from: Available from: https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-cirugiaespanola-36-articulo-indicaciones-resultados-reseccionmetastasis-pancreaticas--S0009739X12002308 . [ Links ]

Received: May 03, 2023; Accepted: November 07, 2023

texto en

texto en