Introduction

Members of the Phallales E. Fisch (Agaricomycetes, Phallomycetidae) are distinguished by the production of short-lived fleshy basidiomes that emerge from a globose egg-like structure. This early stage of development is characterized by the presence of a small and contracted basidiome surrounded by a two or three-layered peridium. One of these layers is a thick and chambered gelatinous matrix that gives a plump appearance to the immature basidiome, and is surrounded by a thin and usually flexible membrane of variable color. Cell expansion leads the rapid emergence process that proceeds nonstop until the full extension of the organ. Glebal maturation starts when the whole basidiome is completely elongated and, starting as a green, chambered, and solid mass, it soon turns into a dark and fetid slime wherein spores are embedded. This slimy gleba acts as an attractant for insects and other invertebrates, as a part of which is considered a passive spore dispersal strategy (Oliveira & Morato, 2000; Johnson & Jürgens, 2010; Teichert et al., 2012; Pudil et al., 2014). Despite their odor and strange and magnificent basidiome morphology, some species have been used by humans; some immature stinkhorns are edible (Laessø & Spooner, 1994; Kibby, 2015; Phillips et al., 2018), and some Phallus spp. compounds have even shown anti-proliferative activity in cancer cells and leukemia cases (Ray et al., 2020).

Phallales constitute a clade within the monophyletic “gomphoid-phalloid” fungi. According to previous studies in stinkhorns (Phallaceae Corda) and lattice stinkhorns (Lysuraceae Corda and Clathraceae Chevall.), they seem to have evolved from a truffle-like ancestor (Hibbett et al., 1997; Hosaka et al., 2006).

The diversity of Phallales in Argentina has been assessed by several mycologists and recorded in a wide variety of habitats and ecosystems, from the humid and high altitude Yungas to the lowlands and semiarid environments of the Chaquean Phytogeographic region (Spegazzini, 1887, 1898, 1906, 1927; Fries, 1909; Molfino, 1929; Wright, 1949a, 1949b, 1956, 1960; Ruiz Leal, 1954; Dring, 1980; Domínguez de Toledo, 1985, 1995; Wright & Wright, 2005; Hernández Caffot et al., 2018).

The genus Lysurus Fr. includes species with hypogeous to sub-hypogeous immature stages, a long-stipitate receptacle ending in vertical arms that can be free or connected by transverse arms conforming a fertile network with or without glebiferous processes emerging from the junctions (Dring, 1980; Domínguez de Toledo, 1995). In Córdoba province in the central area of Argentina, only two species of Lysurus have been recorded, L. sphaerocephalus (Schltdl.) Hern. Caff., Urcelay, Hosaka & L.S. Domínguez [as L. sphaerocephalum in Hernández Caffot et al. (2018, 2020)] (Spegazzini, 1898; Domínguez de Toledo, 1995; Hernández Caffot et al., 2013, 2015, 2018, 2020), and L. cruciatus (Lepr. & Mont.) Henn. (Spegazzini, 1887; Domínguez de Toledo, 1995; Hernández Caffot et al., 2013). The East-center of Córdoba province is partially dominated by remnants of Espinal forests, which constitute a native ecoregion characterized by a mosaic of dry, spiny forest alternating with a savanna, and is currently modified severely by cattle ranching and farming, thus having become a patchy ecosystem (Bertonatti & Coruera, 2000; Lewis et al., 2004, 2009; Zak, 2008; Noy-Meir et al., 2012).

As a result of several mycological expeditions, we published a checklist of the phalloid funga, including the brief description of a putative new species; “Lysurus sp. nov. ined.” (Hernández Caffot et al., 2015). This novelty has now been confirmed based on molecular and morphological analyses. The aim of this study is to provide a full description of L. fossatii, including its phylogenetic placement within the Lysuraceae and images of basidiomes at different maturity stages.

Materials and methods

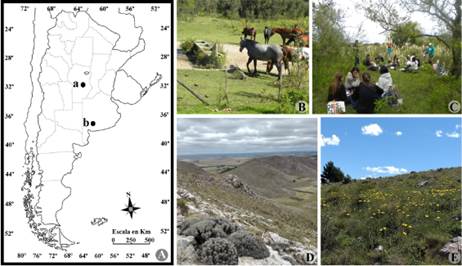

Samples were collected in a forest relic in the Estancia Yucat, Córdoba (32° 22’ 7.89” S; 63° 25’ 34.93” W; Fig. 1). The studied area is situated in the Central District of the Espinal province, characterized by the presence of large specimens of Prosopis alba Griseb. and Celtis tala Gilles ex Planch. (Cabrera, 1976; Lewis et al., 2004, 2009).

Fig. 1 Geographical location of Lysurus fossatii specimens in Argentina. A, site positions at a, Estancia Yucat, Córdoba (32° 22’ 7.89” S; 63° 25’ 34.93” W); b, Sierra de la Ventana, Buenos Aires (38º 03’ 45.9” S; 62º 04’ 00.1” W). B, C, images of vegetation at Estancia Yucat, Córdoba. D, E, images of vegetation at Sierra de la Ventana, Buenos Aires. Color version at http://www.ojs.darwin.edu.ar/index.php/darwiniana/article/view/1014/1251

In some areas of the forest, large individuals of Morus alba L., an exotic species, also occur. Lysurus specimens were collected during sampling trips during March and April 2014 and kept in alcohol 100% for later examination. Specimens were deposited at the Herbario del Museo Botánico (CORD) Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. Samples from Sierra de la Ventana, Buenos Aires were collected at 38º 03’ 45.9” S; 62º 04’ 00.1” W (Fig. 1). Morphological features were observed in the laboratory under stereoscope (NIKON C-PS) and light stereoscope microscope (NIKON SMZ745T) after mounted in 5% KOH, 5% KOH + 1% phloxine, and Melzer’s reagent. Specimens were identified using specific references (Spegazzini, 1887; Lloyd, 1907; Dring, 1980; Domínguez de Toledo, 1995).

For the sequence analyses, DNA was extracted from the glebal tissue using the CTAB (hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide) method as described by Doyle and Doyle (1990). For the amplification of the ITS region, the primer combination of ITS5 and ITS4 (White et al., 1990) was used. PCR reactions were performed in 2.5 ml reaction tubes with 1.13 ReddyMix™ PCR Master Mix (ABgene, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., UK) according to manufacturer instructions. Cycling parameters for the ITS were 1 cycle of 95 ºC for 5 min, 30 cycles of 95 ºC for 1 min, 55 ºC for 30 s, and 72 ºC for 1 min, with a final extension at 72 ºC for 10 min. Amplified products were sent to Macrogen Inc. (Seoul, South Korea) for purification and sequencing with the BigDye™ terminator kit and run on ABI 3730XL.

Phylogenetic analysis

Two ITS sequences of L. fossatii, from the specimens MLHC 2109 CORD (Holotype - 868 pb; GenBank accession number: OM039464) and MLHC 2108 CORD (Paratype - 834 pb; GenBank accession number: OM039463) were generated for this study and combined into a dataset with 27 additional sequences of related and outgroup taxa available from GenBanK (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Phylogenetic position of Lysurus fossatii within Phallales. Bootstrap and posterior probabilities values from up to 50% and 0.5, respectively, are shown.

Sequences were aligned with MUSCLE v3.8.31 (Edgar, 2004). Phylogenetic and molecular analyses were performed using MEGA v. X (Kumar et al., 2018). Evolutionary analyses using Maximum Likelihood were performed in PHYML (http://www.atgc-montpellier. fr/phyml/) with 500 bootstrap replicates. Bayesian posterior probabilities were calculated with MrBayes (Huelsenbeck & Ronquist, 2001). Bayesian MCMC analyses with GTR model custom settings were run with 5,000,000 generations.

Results

Morphological inspection confirmed that our species belongs to the Lysuraceae, whose species are defined by the presence of a long and stipitated receptacle and arms that emerge from an egg-like structure (Dring, 1980, Hosaka et al., 2006). Following a study by Trierveirler-Pereyra et al. (2014), sequences within the Phallaceae, Gastroporiaceae and Lysuraceae were selected to construct our dataset and members of the Protophallaceae and Clathraceae (Protubera canescens G.W. Beaton & Malajczuk (GQ981521.1) (Current name: Ileodictyon gracile Berk.), Clathrus ruber P. Micheli ex Pers. (GQ981500.1) and Ileodictyon gracile P. Micheli ex Pers. (MF503286.1) were used in the present study to root the topology (Fig. 2). Maximum Likelihood bootstrap values as well as bayesian analysis posterior probabilities fully support the hypothesis of a new species within Lysuraceae. Nodes in the upper part of the tree including Gastrosporiaceae and other members of Phallaceae (Mutinus Fr. and Jansia Penz.) were poorly supported.

Taxonomy

Lysurus fossatii

Nouhra, Hern. Caff. & L.S. Domínguez sp. nov. MycoBank: MB #844099. Fig. 3

Diagnosis

Basidiomes present an egg-like structure when immature, surrounded by a light yellow peridium that is otherwise marked by peridial sutures and it opens irregularly from the apex when mature. A thick layer of mucilage is covered by the peridium, in which a short-stipitate basidiome is suspended. Mature specimens up to 65 mm high, white stipe up to 55 mm high × 20 mm diam., fertile portion up to 10 mm high × 25 mm wide, gleba dark green. Basidiospores are smooth, cylindrical with rounded ends, 2.5-3.5 × 5-6.5 μm.

Type

Argentina. Córdoba. Depto. General San Martín, Villa María, 15 km from Tío Pujio, Estancia El Yucat, M. L.Hernández Caffot & L. S. Domínguez, 10-III-2013, MLHC 2109 (CORD-holotype). GenBank accession number: OM039464.

Etymology

Dedicated to the Argentinean botanist Mauro Fossati, for his invaluable contributions to the conservation of the environments where this species occurs.

Macroscopic features

Immature stages globose to subglobose, rooting by a simple rhizomorph that is attached to the base of the stipe. Outer peridium light yellow, with a tubercular surface corresponding to peridial sutures. The internal peridial layer consists of a thick mucilage and hyaline matter compartmentalized by peridial sutures (Fig. 3A-F). Receptacle limited to the upper portion of the stipe. Immature fertile portion 10 mm high × 25 mm wide, globose to cylindrical, greenish, becoming dark green to dark brown when mature (Fig. 3B-J). Stipe up to 55 mm high × 20 mm wide, light cream colored, hollow; wall conformed by 2 lines of chambers made up of hollow longitudinal tubes (Fig. 3I).

Microscopic features

Slender hyphae, 2.5-3.5 μm diam., with mainly enlarged or swollen clamp connections immersed in a mucilaginous matrix (Fig. 3K). Basidiospores cylindrical in side-view, with rounded ends, globose in polar view, smooth, with a light green tinge, 2.5-3.5 × 5-6.5 μm (Fig. 3L).

Habitat and distribution

In wet and mulch-rich soil, in shady areas within the Espinal forests from Córdoba province and among grasses, in areas exposed to insolation in Sierra de la Ventana, Buenos Aires province (Fig. 1).

Additional Specimens examined

ARGENTINA. Córdoba. Depto. San Martín, 15 km from Tío Pujio, Estancia “El Yucat”, 10-III-2013, MLHC 2108 CORD (Paratype); other specimens of L. fossatii, also collected at Tío Pujio, Estancia “El Yucat” on 10-III-2013 and deposited ad CORD herbarium, where analyzed and cultivated at laboratory conditions: MPD21 (CORD): MPD23 (CORD); MPD24 (CORD); MPD25 (CORD); MPD26 (CORD); MPD27 (CORD). Buenos Aires. Pdo. de Tronquist, Sierra de la Ventana (Fig. 3H-I).

Comments

When immature, the receptacle of L. fossatii is composed of a large fertile portion compared to the very small stipe (Fig. 3B). In laboratory conditions, basidiomes emerge after a period of 10 to 15 days. In all the cases we studied, emergence and elongation mainly occur during the night and it might reach the rate of 3-4 cm in 1 minute (this was also observed for Phallus indusiatus Vent., P. galericulatus (A. Møller) Kreisel, Blumenavia rhacodes Möller and L. sphaerocephalus, by G.C. Lloyd (1909). During the expansion process, the meshes of the peridium are still visible within the gleba (Fig. 3F-H), and the solid gleba soon starts to liquefy, becoming dark green to dark brown colored (Fig. 3H-J), an unpleasant scent resembling yeast or decayed peaches is soon released. During the maturation process the stipe also shows changes in coloration and size. The white stipe enlarges up to 55 mm long, and its color turns into a light cream shade (Fig. 3I). Then, a day after emergence of the receptacle, (in laboratory conditions) it shortens and turns orange (Fig. 3J).

Phylogenetic analyses positioned our species within the genus Lysurus and received strong ML bootstrap and Bayesian posterior probabilities support (Fig. 2). Several immature stages (egg-like structures) were found in the field growing single or in small groups and were collected and incubated in laboratory conditions. Photographs of different stages of the basidiomes were used to document the expansion. During the process, we observed a variation in the glebal coloration from green to orange. In later maturation stages (Fig. 3C), the gleba consists of anastomosed arms of orange color, resembling the net structure of the receptacle in L. sphaerocephalus (Dring, 1966, 1980; Hernández Caffot et al., 2018, 2020). However, it is important to highlight that in L. fossatii there is no true receptacular structure as defined by Lloyd (1909). Instead, it is the upper portion of the stem which provides support for the gleba. For this reason, we consider that the basidiome of L. fossatii is characterized by a simple stem-like column. Basidiomes in the Phallales are made up of a high percentage of liquid. Nevertheless, we found them in extremely dry environments and sandy soils (Hernández Caffot et al., 2015, 2018) in the western section of the Espinal forests in a xerophytic environment of temperate and dry climate, usually under trees or shrubs. We have collected specimens of L. sphaerocephalus, P. galericulatus and L. fossatii in the same spots, thus deducing that they share similar nutritional requirements or even the same physiological adaptations to the environment. So far, the distribution of L. fossatii is restricted to Estancia Yucat, Córdoba at the Espinal Phytogeographic Province and Sierra de la Ventana at the Pampean Phytogeographic Province in Argentina (Fig. 1).

A feature of this species we consider exceptional for the group is the external morphology of the immature stages: L. fossatii exhibits a peridium with light yellow tinge and the presence of the peridial sutures confer a trabecular appearance, unlike other known Lysurus species whose peridium is smooth. Trabecular appearances of the egg-like immature stage has been also described for Clathrus crispatus Thwaites ex E. Fisch. by Lloyd (1909) and several other species of the genus (i.e. Cheype, 2010, Fazolino et al., 2010). In those cases, the external morphology of the peridium reflects the structures in the inner basidiome, partitioned in arms and meshes. The morphology of the emerged basidiomes of L. fossatii, its small size, white stipe and its green gleba with sutures resemble Phallus glutinolens (A. Møller) Kuntze (Trierveiler Pereira et al., 2009). However, the absence of a pileus or receptaculum and a perforate apex characteristic of Phallus species allow a clear separation even in the field. Specimens of L. fossatii have been collected in recent field expeditions in Buenos Aires province at Sierra de la Ventana - Cerro Guardián (Fig. 1); however, those specimens were not included in this analysis due to preservation issues, images of the mature basidiomata reflect the typical macro-morphology of this taxon (Fig. 3I).

A recent publication by Melanda et al. (2021) provided invaluable data on molecular phylogeny and geographical distribution of stinkhorns, including Lysuraceae, with some systematic resolutions. We add to their conclusions that Lysurus sphaerocephalus is indeed a name validated by an identifier-issued citation (Hernandez Caffot et al., 2020) according to Art. F.5.1. We also correct the latin case of this name to Lysurus sphaerocephalus herein. The described macro and microscopic diagnostic features of Lysurus fossatii make it a unique species phylogenetically placed within Lysurus and clearly separated from the previously described ones.

Fig. 3 Lysurus fossatii basidiomes in natural habitat and cultured at laboratory conditions. A, external view of immature stage “egg-like structure” showing the tubercular surface of the peridium. B, longitudinal section of immature stage, exhibiting the basidiome, the peridial sutures and the internal mucilage layer. C, transversal slice of an immature stage showing a superficial view of the upper portion of the gleba. D, E, extracted basidiome from the egg-like structure showing the rhizomorph attachment. F, G, emerging basidiome. H, mature basidiome in natural conditions. I, dry mature basidiomes in longitudinal section. J, overripe basidiome in laboratory conditions. K, clamped hyphae from the mucilage layer. L, basidiospores showing the smooth surface (left image) and ecuatorial view (wright image). Bars: A-J = 1 cm. Bars: K-L = 1 μm. A-G and J-L corresponds to type material MLHC 2109 (CORD), and H-I corresponds to material from Sierra de la Ventana, Buenos Aires. Color version at http://www.ojs.darwin.edu.ar/index.php/darwiniana/article/view/1014/1251

uBio

uBio