KEY POINTS

Current knowledge

• For patients with melanoma and positive- SLNB risk of recurrent disease is still sub stantial. Also in those patients, monitoring with ultrasound (active surveillance) has recently been adopted as an alternative to immediate lymphadenectomy.

Article contribution

• This study confirms prognostic indicators that impact on survival of CM patients. Most importantly adds real-world data of results on (actually preferred strategy) ac tive surveillance in positive-SLN melanoma patients in a reference specialized center in Argentina.

Tumor progression has been reported in about one third of all patients diagnosed with clinically localized primary cutaneous melanoma (CM) as locorregional nor distant recurrences1. Different factors have been recognized and used in scoring systems to predict the risk of recurrence. Anatomic location, ulceration, age, mitotic rate and positive-SN represent some of those variables evaluated in different series. Some studies also have investigated the positive sentinel node characteristics and correlated them with outcomes and patient survival. Moreover, there is a historically wide range of survival for stage III melanoma patients and this trend increased even more in the current 2017 American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) eight edition2.

Status of the regional lymph nodes in patients with clinically localized CM is the most important prognostic factor3-7. Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is the best-known and precise procedure to assess the lymph node status in these patients as demonstrated in the first Multicenter Sentinel Lymphadenectomy Trial (MSLT-1)8,9. Moreover, with an accountable less morbidity than elective completion lymph node dissection (CLND) which was previously the strategy of choice for staging regional lymph nodes in clinically node-negative patients10,11. Only approximately 20% of the patients with positive sentinel lymph node (SLN) have metastatic tumor cells in the other non-sentinel lymph nodes (NSNs). Results of two randomized controlled trials (MSLT- 2 and DeCOG-SLT) posteriorly showed that immediate CLND did not increase melanoma-specific survival and proposed a change in the timing of that intervention for those patients with subclinical metastatic-NSNs; establishing that the active surveillance with ultrasound and without immediate CLND is a safe and less morbid option in these patients12,13. In addition, several trials have established the utility of adju vant systemic therapy in patients with stage III cutaneous melanoma14-16.

We aimed to investigate prognostic indicators associated with disease recurrence (regional and distant) and survival in positive-SLNB patients treated at our Institution before and after MSLT- 2 era.

Material and methods

A retrospective evaluation of patients with positive- SLNB for cutaneous melanoma between January 2010 and December 2020 at the Sarcoma and Melanoma Unit of our General Surgery Department was carried out. We includ ed patients who had a clinically localized and node-nega tive cutaneous melanoma of trunk and extremities, aged ≥18 years and had at least 1 positive (metastatic) SLN. Patients who had loco-regional or distant disease during the preoperative staging were excluded. Institutional Re view Board permission was obtained for this study.

Multidisciplinary institutional melanoma tumor board (MDT) meets once every week and all patients are discussed at initial consultation and previous to start de finitive treatment. We recommended SLNB in all patients with cutaneous melanoma and a Breslow thickness ≥1mm or ≥0.75mm with associated risk factors (ulceration, high mitotic count or Clark level invasion IV/V). Since 2020 we discussed the indication in thin melanomas when the probability of nodal metastasis was ≥10% (using the Sen tinel Node Metastasis Risk Prediction Tool developed by Melanoma Institute Australia based on a published risk prediction model)17,18. The SLN was defined as the lymph node (or nodes) that first receives direct lymphatic drain age (evaluated with blue dye and/or radioactive isotope) from the primary melanoma. All patients underwent surgical procedure as described by Morton19. In the same surgical procedure definitive treatment of primary lesion was done as appropriate (wide local excision of primary tumor with proper margins or wide excision of scar of previous incomplete surgery).

Clinical features (age at diagnosis and sex) and prima ry tumor features (histologic subtype, Breslow thickness divided as < 2 or ≥ 2 mm, ulceration, mitotic rate, lympho vascular invasion) were recorded. Meticulous pathologic examination was done in all SLNs using H&E analysis and immunohistochemistry (with S-100 and HMB-45) by the same expert pathologist (FV). Some SLN specimens were re-examined and if necessary further sections were cut and stained ensuring that all the patients were as sessed under the same protocol. Sentinel node (SN) fea tures analyzed were: number of SN harvested during SLNB, maximum size of largest melanoma deposit (Max Size) categorized as ≤ 2 mm or > 2 mm, intranodal loca tion of melanoma deposits as described by Dewar et al20 and presence of extranodal extension of tumor (ENE).

According to the evidence published in literature we started our active surveillance (AS) protocol with out CLND in positive-SLNB patients in June 2017. Previ ously, all patients were offered CLND. Hence, depending on management, we divided the cohort into two groups: Group A (CLND) and Group B (active surveillance, AS). All patients were followed-up according to usual protocol which is every 3 months the first 2 years, then every 6 months until the 5th year and then annually with physi cal examination, chest radiography and hepatic ultra sound. AS protocol adds an ultrasound of the mapped node basin. The indication for systemic adjuvant treat ment was discussed with the patients after multidisci plinary tumor board evaluation. The immediate CLND was not a requirement to deliver adjuvant treatment.

Any-site recurrence free survival (RFS) was defined as first recurrence of melanoma at any site from time of SLNB, diagnosed by clinical and/or imaging studies and confirmed on biopsy when feasible. Isolated nodal recur rence (INR) was defined as recurrence in SLN-basin with out other affected site. Distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) was defined as distant recurrence beyond the regional node field identified during follow-up as either first or subsequent recurrence. Melanoma-specific sur vival (MSS) was defined as melanoma-related death from time of SLNB.

The relationship of categorical clinic-pathologic pa rameters between the different groups was assessed ini tially. Qualitative variables were compared using χ2 and Fisher’s exact test, when applicable, while Student’s t-test was used for quantitative variables. Quantitative vari ables are described as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) and qualitative variables as percentages. Patients were compared accord ing to systemic recurrence, performing a univariate anal ysis to identify the factors associated with it. MANOVA was used for multivariate analysis, including variables identified as p <0.25 in univariate analysis. All statistical analyses were done by use of XLSTAT 2020, 4.1.1023. An arbitrary p value of less than 0.05 was considered as sig nificant.

Consent to participate: Due to the retrospective nature of this study, the Ethics Committee waived the requirement for written informed consent: however, all patients signed the surgical consent form.

Results

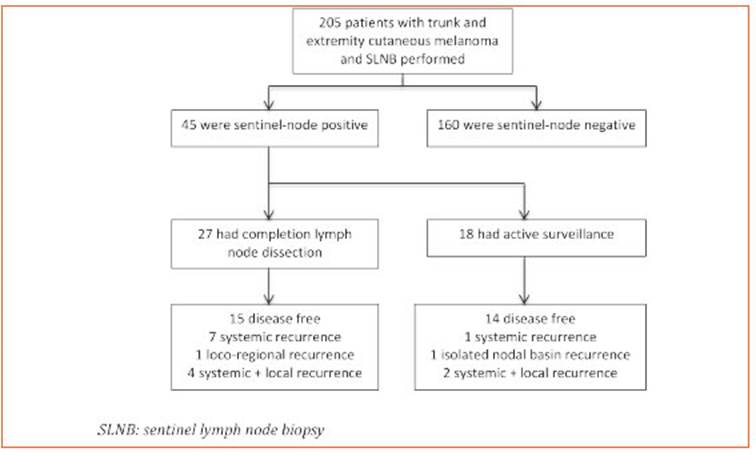

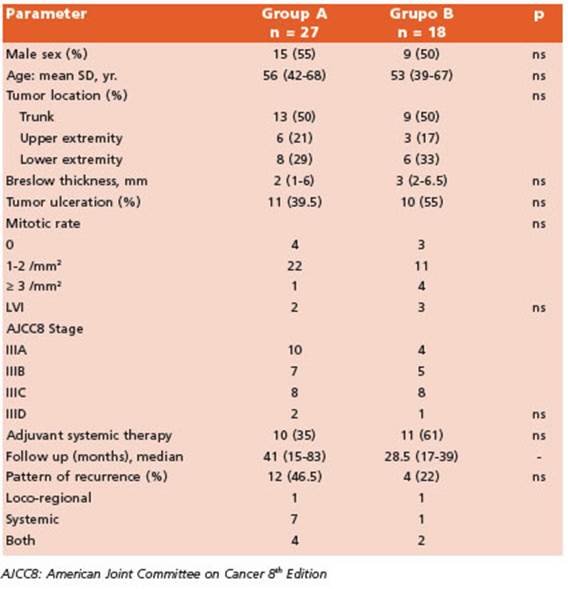

During the study period we performed 205 SL NBs. Among these, 45 patients (22%) had at least one positive SLN. Twenty-seven patients (60%) underwent CLND (Group A) while the remain ing 18 (40%) had an active surveillance (Group B) (Fig. 1). Characteristics of patients in both groups are listed in Table 1.

Table 1 Characteristics of patients undergoing complete lymph node dissection (Group A) and active surveillance (Group B)

Among the patients in Group A, 10 (37%) had metastatic disease in the completion specimen: 5 patients one positive non-SLN and 5 patients had ≥ 2 positive non-SLNs. CLND resulted in up staging, according to the American Joint Com mittee on Cancer 8th edition cancer staging manual, in 4 of 10 cases (40%).

The median follow-up of the whole cohort was 36 months (25th to 75th interquartile, 16.5-66.5 months). We observed a total of 16 (35%) recur rences at any site (10 patients having disease re currence before year one of follow-up; median time to disease recurrence was 10 months) and estimated 5-yr RFS at any site was 60% (CI95%, 0.39-0.77). Of them, only 50% (8/16 patients) re ceived adjuvant treatment and had Stage III C/D disease. We observed 44.5% recurrences in Group A (12/27, median follow-up 41 months) and 22% in Group B (4/18, median follow-up 28.5 months); p = 0.20.

There were two (2/45; 4%) exclusive loco-re gional recurrences: one tumor satellite near sur gical scar of primary tumor that was resected and, in Group B, an isolated nodal basin recur rence detected by ultrasound during follow-up. That patient (stage IIIB without adjuvant treat ment) underwent complete nodal basin dissec tion without post-operative morbidities. Both patients are alive and without evidence of dis ease at last follow-up.

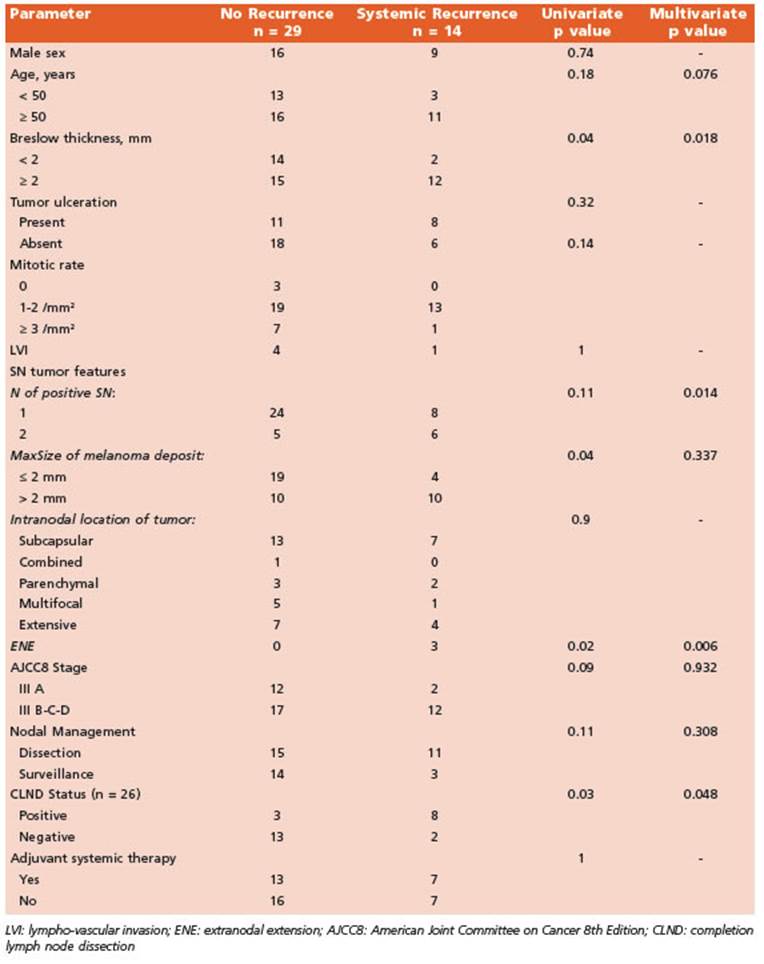

Estimated 5-yr DMFS of the whole cohort was 65% (CI 95%, 0.44-0.81) with no differ ences between groups (p = 0.41). We observed eight (18%) exclusive systemic recurrences and six (13%) patients had both systemic and loco-regional disease recurrence. When analyzed, we observed age ≥ 50, Breslow depth > 2 mm, MaxSize of melanoma deposit > 2 mm, ENE and CLND status (positive) to be associated with occurrence of systemic disease on univariate analysis. Multivariate analysis showed Breslow depth > 2 mm, ENE, number (≥ 2) of positive SN and CLND status as independent risk factors of DMFS (Table 2).

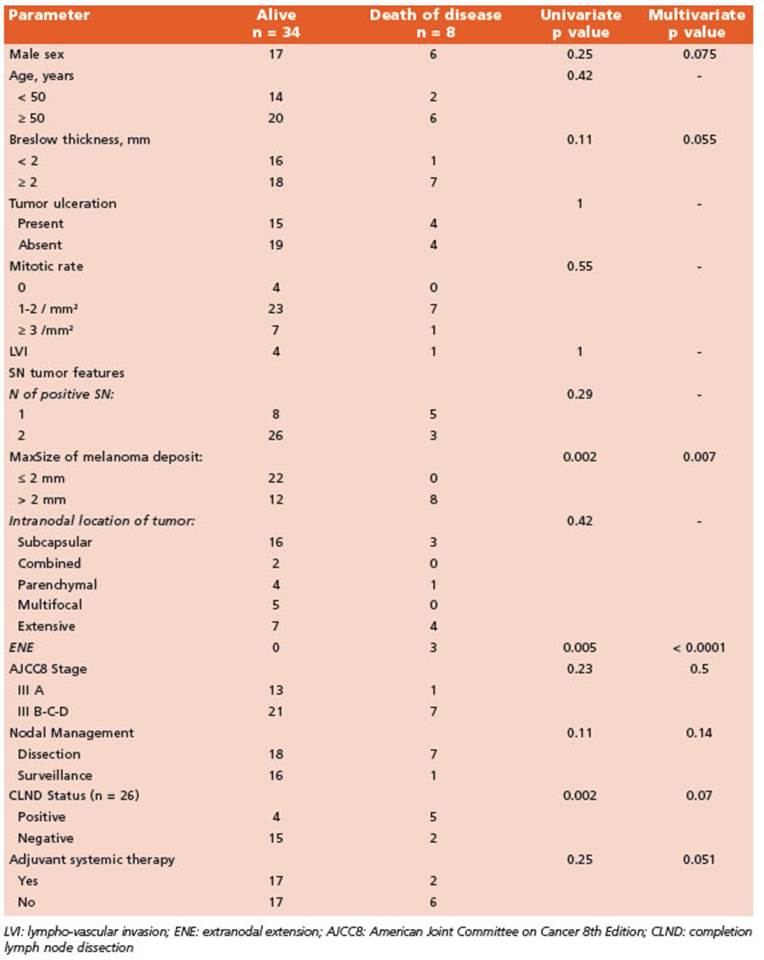

During the study period eight patients died of melanoma while other three died for other not related causes and were excluded from the analysis of MSS. Estimated 5-yr MSS was 73% (CI 95%, 0.59-0.89) with no differences between CLND and AS groups (log-rank p = 0.37). Factors associated with MSS were sex (male), Breslow thickness, ENE and MaxSize of melanoma de posit in SLN, CLND status (positive) and use of adjuvant systemic therapy. Multivariate analy sis showed ENE and MaxSize > 2 mm of mela noma deposit were independent predictors of MSS (Table 3).

Discussion

SN-positive patients have a significantly increased risk of developing any form of recurrence compared to SN-negative patients. In the past, several studies have identified parameters predictive of clinical outcomes in SN-positive patients. Breslow thickness, older age and Non-SN positivity (but not number of nodes) in CLND demonstrated to be independent predictors of survival. But additionally, management of patients with cutaneous melanoma has had several changes in the last decades21. Despite its retrospective nature and small sample size, the results of our study are in line with previous studies and analyses the outcomes of positive-SN patients (with a signifi cant number of clinicopathologic parameters assessed) before and after MSLT-II era and adju vant therapies in a Latin-American population where information is still scarce22,23.

We found that some primary tumor (Breslow > 2 mm) and SN tumor (extranodal extension and ≥ 2 positive SN) features as well as CLND status (positive) were independent risk factors of DMFS. Non SN positivity in CLND has been shown to be a significant predictor of survival and poor DMFS; this last parameter being a more reliable measure because it takes into account as an endpoint a clinical situation that could be life-threatening and might lead to patient’s death by disease. Results of MSLT-II and DeCOG-SLT showed that immediate CLND in patients with a low tumor burden in the SLN was not associated with improved melanoma specific survival. As a result, active nodal surveillance emerged as an option delaying the CLND in the true 20% positive-NSN group without adverse oncologic impact and avoiding it in the rest of the patients. In the present study positive im mediate CLND (majority performed prior MSLT-II era) was an independent risk factor of DMFS as in other studies; but we saw no impact in dis ease specific survival nor DMFS when we ana lyzed the management of nodal basin (active surveillance vs. lymphadenectomy) according to the actual evidence in the literature12,13,24,25.

Moreover, SN tumor characteristics such as MaxSize or tumor penetrative depth have prov en to be associated with clinical outcomes26-28. Optimal MaxSize cutoff for prognostic strati fication is not well standardized given the fact that histologic protocols for sampling SNs vary between studies. Nonetheless, MaxSize is pre dictive of survival as shown in different stud ies even with different cutoffs. The Rotterdam Group29,30 showed association with disease sur vival when categorized into <0.1 mm, 0.1-1 mm and >1 mm while the 2 mm cutoff was a signifi cant predictor of DFS and DMFS in the study by Murali et al28. In our study we found a statisti cal significant association of this value (2 mm) with DMFS and MSS. Some studies argue against the use of size of tumor deposits as a criterion to estimate prognosis. We had 6 patients with MaxSize < 1 mm (micrometastases) and, after a median follow-up of 58.5 (IQR, 16-93) months, all are alive without disease recurrence. Due to the small size of this subgroup we cannot determine the clinical significance of melanoma microme tastases in SNs.

Although not statistically significant, a trend towards worse DMFS and MSS was observed in older patients and male sex respectively. None theless, in a previous report of the role of SLNB for cutaneous melanoma in elderly patients we described poorer overall survival in patients ≥ 70 years31. Age > 50 years has been associated with poorer MSS in other studies28.

Given the results of the nivolumab, pembro lizumab and dabrafenib-trametinib trials and, in light of the results of MSLT-II and DeCOG tri als, adjuvant therapy is a reasonable strategy even in those patients not undergoing CLND. But real world data show different percentages of patients actually receiving it. Broman et al. described that adjuvant systemic therapy was given in 39% of patients who underwent CLND and 38% who underwent active surveillance28. Nijhuis et al32 reported a higher use of adjuvant therapy in AS patients (52%, 32/61) while Farrow et al. reported 68.8%33. In our series, 46% (21/45) of our cohort received adjuvant systemic thera py and specifically 61% of patients under AS. The most frequent indication was single-agent anti- PD-1 immunotherapy (62%). Active surveillance approach is nowadays the preferred strategy in SN-positive patients. In fact, we have chosen AS in more than 80% of our patients since we start ed our protocol in June 2017 without an impact in RFS at any site, DMFS or MSS.

There are limitations in this current study. The most important is its retrospective nature and relative small number of patients. Ulcer ation of primary tumor was not a strong factor, but should be in a larger future cohort. However, this study analyses a wide range of clinicopath ologic parameters and its impact on survival. To the best of our knowledge, is the first national study to report this information in a Latin Amer ican population.

The results of this study in a SN-positive Argentinian cohort shows that primary tumor and SN (tumor deposit) features in melanoma give important prognostic information. Active surveillance strategy has been adopted for most positive-SLNB cutaneous melanoma patients25.