The geographical distribution of the Chaco Chachalaca (Ortalis canicollis) in Argentina is apparently well known. After all, chachalacas are remarkably noisy birds with a large body mass (479-678 g; Pagano y Salvador 2017) that used to be hunted for food. However, there is a discrepancy in the literature regarding its presence in the provinces of Entre Ríos and Corrientes (Argentinean Mesopotamia). The ear-ly work by Vaurie (1968) did not map the species for the Mesopotamia, and neither did it occur in subse-quent studies (e.g., Blake 1977, del Hoyo et al. 1994, del Hoyo and Kirwan 2020).

In Argentina, the Chaco Chachalaca was not re-ported for Mesopotamia in the checklists done by Zotta (1944) and Olrog (1979). The first report of chachalacas for Mesopotamia can be found in the field guide by Canevari et al. (1991), which was repeated afterwards in other field guides and checklists (e.g. Narosky y Yzurieta 2003, de la Peña 2006 [but see de la Peña 2012], Rodríguez Mata et al. 2006). Recently, Dardanelli et al. (2018) list the Chaco Chachalaca in northern Entre Ríos Province with basic data on habitat, ecoregion and relative abundance, based on their own observations, bibliography and citizen science initiatives. Finally, Pearman and Areta (2020) map this species for northwestern Entre Ríos and southwes-tern Corrientes based on "a selection of trustworthy records from citizen science initiatives” (pp. 36). We present data suggeting that the species colonized the Mesopotamia from Santa Fe Province by crossing is-lands of the Paraná River, probably starting during the period 1900-1960. We document that Chaco Chachalaca has expanded its range within Mesopotamia approximately 300 km to the east since that time.

Methods

We reviewed historical sources on Mesopotamian birds starting from the Spanish colonial period in the 18th Century until 2018. We also checked online da-tabases of museums of Argentina and elsewhere, and reliable sight records, photographs and recordings of vocalizations (including bibliographic records, and Xeno-canto and eBird online databases) up to De-cember 2020. Historical localities of most specimens were obtained from Hellmayr and Conover (1942), and Vaurie (1968). To make maps, we used the geo-graphic coordinates provided by the original source when available, and we checked the coordinates of historical localities using Paynter (1995).

We estimated the area of inland Mesopotamia colonized by Chaco Chachalaca using QGIS 2.18.20 (QGIS Development Team 2018). For this, we defined a vector layer by making a 20 km-radius buffer around each locality in Entre Ríos and Corrientes provinces, and the borders of these buffers were united to crea-te convex polygons. The localities we used to do this were the same as those in the occurrence maps.

We visited most of the localities in Entre Ríos and Corrientes from where the species was reported from 1992 to the present, in order to check the bibliogra-phic records and citizen-science based information. We also gathered testimonials from elders in Entre Ríos and Corrientes, that had observed and hunted chachalacas in the past. Data on chachalaca habitat use, diet and behavior were obtained at estancias Tari, Cuenca and La Paz (Curuzú Cuatiá Department, Corrientes Province [29°10’ S, 58°25’ W]). Vegetation types frequented by chachalacas and plant species consumed were identified following Jozami and Muñoz (1983) and Carnevali (1994).

Results

Historical data from islands on the Paraná RiverThe earliest reports and drawings of Chaco Chachalacas in the Argentinean section of the Paraná River come from Santa Fe and Chaco provinces, and can be found in the chronicles of the Jesuit missio-naries Martin Dobrizhoffer and, especially, Florian Paucke, who lived in those provinces from 1752 to 1767 (Paucke 1944, Dobrizhoffer 1967). Paucke was in charge of the Mission San Javier (currently San Javier [30°34’S, 59°55’W]) and Dobrizhoffer of the Mission San Jerónimo del Rey (currently Reconquista [29°8’S, 59037’W]), both located in northern Santa Fe Province, until the Jesuits were expelled from the Spanish colonies in 1767. Both priests wrote natural history notes in German and used the name “scha-rrat” for the species. The most common vernacular Argentinean name for Chaco Chachalacas is still “charata” and is probably of Amerindian origin. Both priests also hunted the species for food. Unfortunate-ly, the manuscripts of Paucke and Dobrizhoffer were deposited in Austrian monasteries and remained unknown to science until the 20th Century. These ear-ly historical sources mention Chaco Chachalacas as being present on islands in the Paraná River. Between 1752 and 1767, Pauke (1944) reported chachalacas as abundant in an island on the Paraná River near the Mission San Javier.

Another historical record is found in Captain Page’s book (1859) from the Water Witch expedition to the Paraná River in Argentina. The book mentions members of the expedition hunting “gallinas de monte” and “pavas de monte” in an unnamed island north of the town of La Paz (Entre Ríos Province) on 5 September 1855. In fact, a Chaco Chachalaca spe-cimen was collected by the Page expedition and was deposited at the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution (USNM Birds 85561). It has a handwritten label that has been interpreted as “Panamá”, an obvious mistake, as Chaco Chachalacas do not occur in that country. Based on Page’s book we interpret the handwritten label as “Paraná”, meaning the river rather than the city with that name. However, its precise locality remains unknown.

In the Museum of Natural Sciences Florentino Ameghino (Santa Fe, Argentina) there is a Chaco Chachalaca specimen (MFA-ZV-A 1035) from Isla del Medio, Santa Fe Province (29°55’S, 59°47’W), collected on 11 September 1950.

Historical data from Entre Ríos and Corrientes provincesAzara (1805) commented that Chaco Chachalacas in the Paraguay and Río de la Plata regions were only found north of the 27° parallel. With this statement he excluded the species from Corrientes and Entre Ríos provinces. As a Spanish colonial official, Azara traveled several times on horseback along the Camino Real, from Baxada (nowadays the city of Paraná in Entre Ríos) to the city of Corrientes, and beyond to Asunción in Paraguay (Contreras Roqué 2011). His first trip took place between 13 January and 3 Fe-bruary 1784. Azara also visited northern Corrientes and the Iberá marshes from 16 November 1787 to 3 January 1788 (Contreras Roqué 2011). He hunted and collected specimens along the roads and wrote field journals that are still available. It is highly unlikely that he missed the conspicuous chachalacas in the Argentinean Mesopotamia.

Doering (1874) did not find Chaco Chachalacas in his collecting expedition to the Guayquiraró River (political border between Entre Ríos and Corrientes provinces) in January and February of 1873. Chaco Chachalacas are not mentioned for Corrientes in the catalog of Rojas Acosta (1897), a botanist and natura-list who knew the species from the Chaco Province. There was no mention of Chaco Chachalacas in the detailed checklist of Entre Ríos birds from Freiberg (1943) either. The well-known naturalist W.H. Par-tridge traveled through most of Corrientes Province (1960-1961), collecting hundreds of avian specimens for museums in the USA and Argentina, but never collected a Chaco Chachalaca (Partridge 1962, 1963, 1964, Short 1971, Darrieu and Camperi 1998).

The first known specimens from Argentinean Mesopotamia were collected by Carlos Ríos in June 1955. He obtained two Chaco Chachalaca speci-mens at Paso Yunque (La Paz Department, Entre Ríos [30°21’S, 59°15’W]), a locality on the Guayquiraró Ri-ver. Interestingly, this place is located just 20 km from the collecting localities of Doering (1874), where he did not find chachalacas at that time. The specimens (MFA-ZV-A 1028 and 1029, a male and an immature individual) are deposited in the Museum of Natural Sciences Florentino Ameghino, but were reported much later in Ordano and Bosisio (2001).

Two other Chaco Chachalaca specimens were collected in 1981 at Malvinas Norte (29°37’S, 58°58’W), Departamento Esquina (Corrientes Province) and are deposited at the Los Angeles County Museum (LACM 93202 and 93203). Lastly, two mounted unsexed speci-mens are at the Museo de Ciencias Naturales of Mercedes, Corrientes Province, unfortunately without labels, but presumably collected in the 20th Century in this province (as are all other labeled specimens of the mu-seum).

Interviews with local residentsThe owner of estancias Tari and Cuenca (Mr. Trommenhausen) at Departmento Curuzú Cuatiá, Corrientes Province, had seen, photographed and hunted chachalacas since 1945. Near those localities, at Estancia La Paz, chachalaca groups had been seen and heard since 1942 (CF pers. obs.). In Las Cuchillas (30°14’15”S, 59° 4’47”W), Departmento Sauce, sou-thern Corrientes Province (next to Entre Ríos Provin-ce) a local resident called José Ayala reported hunting chachalacas for food in 1969. Finally, a more recent record has been reported from Loma Limpia (30°39’S, 58°57’W) next to the Feliciano River in Departamento Federal (Entre Ríos Province): a 56 year old farmer (Juan Short), assured us that in his youth there were no chachalacas, and that he has observed them in the area since approximately 2010. Interestingly, nowa-days Chaco chachalacas are locally common in this area: it has been constantly recorded in northern Entre Ríos Province since at least 2015 (EAJ and SD pers. obs.; eBird 2021, Jordan et al. 2021).

Range expansiónUsing all the above information, we conclude that Chaco Chachalaca has expanded about 300 km to the northeast and 200 km eastwards inland in the Argen-tinean Mesopotamia, maybe during the first half of the 20th Century. Our estimates indicated a colonized area of approximately 24844 km2.

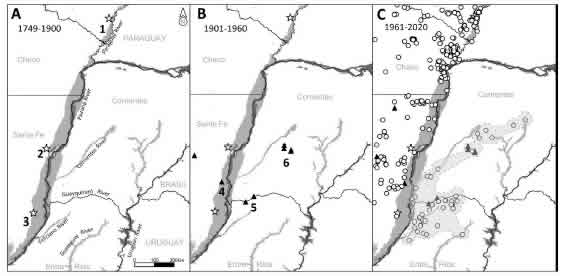

Figure 1: Historical and recent localities of Chaco Chachalaca (Ortalis canicollis) in Argentinean Mesopotamia. Paraná River floodplain is depicted in dark grey. A) Period from the first known records of the species in Argentina, until 1900 (depicted by stars): (1) Azara's record from Paraguay (currently Formosa Province), (2) Dobrizhoffer's record from Misión San Jerónimo del Rey (currently Reconquista), (3) Paucke's record from Misión San Javier (currently San Javier). B) Period from 1901 to the earliest known inland records in Entre Ríos and Corrientes provinces (depicted by triangles): (4) specimen collected at Isla del Medio, (5) records from Paso Yunque and Las Cuchillas, (6) records from estancias La Paz, Tari and Cuenca. C) Period of recent records (depicted by circles, sourced primarily from eBird): dashed lines delimit the estimated colonized area of Chaco Chachalaca during its expansion process.

In order to visualize the colonization process, we developed a map (Fig. 1) in which we divided all the Chachalaca records into three periods: 1749-1900, 1901-1960, and 1961-2020. The first period is cha-racterized by a scarcity of records, and ranges from Azara’s first records for Argentina, up to 1900; that is, 26 years after Doering’s expedition. The last two periods are of 60 years each: the middle one encom-passes the first five records of Chaco Chachalaca in inland Mesopatamia, and the last one highlights the current increasing amount of records.

Natural history informationOne of us (RM Fraga) was alerted in 1988 of the presence of Chaco Chachalacas at Estancias Tari and Cuenca. We visited the place in August 1991 and found three territorial groups along the Arroyo Villanueva. Their territorial group calls and other calls were recorded and can be found in Xeno-canto (XC454139, XC54140). The chachalacas roosted in gallery forests that had at least 14 species of native di-cot trees, arborescent cacti and two species of palms. They ate flowers of a native Schinus shrub and fruits of the introduced tree Melia azederach, as well as those of arborescent cacti and the native palm Arecastrum romanzoffianum. One of the groups also visited the nearby savanna, foraging on the ground under Pro-sopis and Aspidosperma quebracho-blanco trees. At Estancia La Paz, we saw the chachalacas mostly along a smaller tributary of the arroyo Villanueva, where they also roosted.

Discussion

We found that Chaco Chachalacas appear to have increased their distribution to the east in recent decades. Nowadays, many land owners in Mesopotamia protect chachalacas (Giraudo et al. 2003), which are regarded as a tourist attraction. We hypothesize that Chaco Chachalaca will soon reach the Uruguay River basin, given the general trend in the direction of its range expansion and the continuity of appropriate habitats (i.e. dry forests) along the main rivers (e.g. Guayquiraró, Feliciano, Gualeguay, and Corrientes).

It is difficult to propose a reliable explanation for the recent colonization of Mesopotamia by Chaco Chachalaca. Chaco woodlands occur in a northeastern block in Santa Fe Province, known as "Cuña Boscosa”. These woodlands are found along the western bank of the Paraná River, and become increasingly narrow and fragmented southwards (Cabrera 1976, Lewis and Pire 1981, Carnevale et al. 2007), ending near the town of San Javier, Santa Fe Province, exactly where Pauc-ke (1944) found the species. Our data suggest that the Cuña Boscosa area might be the source of our Mesopo-tamian chachalaca population. It is likely that the po-pulations from that source area have achieved several generations with high reproductive success, with the consequent expansion into territories with appropria-te habitats on the other side of the Paraná River. As our data show, this process seems to have occurred during the first half of the 20th Century.

The extractivist development of the Cuña Boscosa began in the late 19th Century, and then increased in the first decades of the 20th Century, together with the growing human settlements (Brac 2017). Since the first half of that century, the Chaco woodlands in the Cuña Boscosa have been increasingly modified due to intense logging, reduced today to secondary forests (Carnevale et al. 2007, Alzugaray et al. 2006). Further research is needed to test whether the displa-cement of chachalacas towards inland Mesopotamia has been triggered by the increasing fragmentation of the Cuña Boscosa since the early 20th Century.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editor for English improvement and conceptual comments. In the same way, two anony-mous reviewers enriched the work. C. Henschke pro-vided us with the first information on the presence of chachalacas in Corrientes Province. We thank A. Parera for providing information and photographs of Corrientes chachalacas. Fabricio Reales provided im-portant references for this study.

uBio

uBio