Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Enfoques

versão On-line ISSN 1669-2721

Enfoques vol.27 no.1 Libertador San Martín jun. 2015

ARTÍCULOS ORIGINALES

Oral interaction in the classroom: An up-close view at the English as a Foreign Language Teaching Program at Universidad Adventista del Plata

Interacción oral en el aula: el Inglés como Programa de Enseñanza de Lengua Extranjera en la Universidad Adventista del Plata

Oral interação na sala de aula: Programa de Ensino de Inglês como Língua Estrangeira na Universidad Adventista del Plata

María Cecilia Bonavetti

Universidad Adventista del Plata E-mail: mariabonavetti@doc.uap.edu.ar

Recibido: 04/02/2014

Aceptado: 06/04/2015

Abstract

This study examines the way in which English majors and their teachers at Universidad Adventista del Plata interact with one another in the foreign language classrooms when they are involved in oral communication with pedagogical aims. The information obtained has been compared to and contrasted with the types of oral interaction that occur in the ideal classroom as understood by “Communicative Language Teaching”, one of the most widely accepted approaches to language teaching around the world. The results show that in spite of certain areas where improvement could be made, the classes observed can be considered communicative in the strictest sense of the word.

Keywords: Oral Interaction; Classroom Interaction; TALOS (Target Language Observation Scheme); Communicative Language Teaching; English as a Foreign Language Teaching Program; Universidad Adventista del Plata.

Resumen

Este estudio examina la forma en la cual alumnos y docentes del Profesorado de Inglés de la Universidad Adventista del Plata interactúan oralmente y con fines pedagógicos en el aula de aprendizaje de un idioma extranjero. La información obtenida ha sido comparada y contrastada con los tipos de interacción oral que ocurren en el aula ideal, tal y como la presenta el Método Comunicativo de la Enseñanza de la Lengua, que es el método de enseñanza de lenguas extranjeras actualmente más aceptado alrededor del mundo. Los resultados muestran que a pesar de haber ciertas áreas que podrían mejorarse, las clases observadas pueden ser consideradas comunicativas en el sentido más estricto de la palabra.

Palabras clave: Interacción oral; Interacción en el aula; TALOS (Target Language Observation Scheme); Método Comunicativo de la Enseñanza de la Lengua; Profesorado de Inglés; Universidad Adventista del Plata.

Resumo

Este estudo examina a forma com que os alunos e docentes do Curso de Letras Inglês da Universidade Adventista del Plata interagem oralmente e com finalidade pedagógica na sala de aprendizagem de um idioma estrangeiro. A informação obtida foi comparada e contrastada com os tipos de interação oral que ocorrem na sala de aula ideal, tal como é apresentada no Método Comunicativo do Ensinamento da Língua, que é o método de ensinamento de idiomas estrangeiros que atualmente tem maior aceitação no mundo. Os resultados demonstram que, apesar de existirem certas áreas que poderiam ser melhoradas, as aulas observadas podem ser consideradas comunicativas, no sentido mais estrito da palavra.

Palavras chave: Interação oral; Interação na sala de aula; TALOS (Target Language Observation Scheme); Método Comunicativo do Ensinamento da Língua; Curso de Letras Inglês; Universidade Adventista del Plata.

Introduction

It is well known that not only language researchers but also teachers have always been attracted to carrying out their investigations within the classroom context. For the most diverse reasons, they have used the classroom as the source of information to test hypotheses, to support theories, to assess performance (that of students’ as well as that of teachers’), or to evaluate outcomes, among others.

Classroom observation began in the 1960s as a way to provide feedback to trainee-teachers in their practice. From then on, “there has been an increasing attempt in research on teaching and learning from instruction to relate the major features of teacher and student behavior in classrooms to learning outcomes”.1 Chaudron explains that the objective of such research has been to determine the variables that foster academic achievement and the ones that deter it. In doing so, different methods can be applied, such as the experimental method, ethnography, interaction analysis, observation schemes or cases studies.2 The choice among them is directly connected to and will result from the observer’s purpose. For instance, a materials writer will focus on the learners and how they cope with certain activities, but a teacher trainer may concentrate on the trainee teacher and the way he/she manages the class. In my case, being not only a teacher, but also the head of the English department at Universidad Adventista del Plata, my purpose is to evaluate the way students and teachers interact in the classrooms to see how this may impact and influence learning.

Classroom behavior has been observed, described and analyzed from many different angles. It is important to highlight the fact that the conceptions each observer has on the theories of learning and the theories of language acquisition will shape the way in which those behaviors are understood and interpreted. Furthermore, much has been written about the importance of “interaction” in helping students achieve their learning objectives. In this arena, theorists who view language learning in more social terms agree on the belief that interlocutors’ exchanges are vital in promoting language development. However, their views on “how” these exchanges facilitate the process are different, even distant and opposing from one another, as it will be reviewed later in this work. Malamah-Thomas maintains that

the interaction of the classroom, the assumption and assignment of different kinds of participant role [is what] mediates between teaching and learning. It is therefore of crucial important that the factors which enter into this interaction should be subjected to careful and critical examination and their implications for pedagogic practice explored in the context of actual classrooms.3

It is clear, then, that regardless of the position taken, interaction is part and parcel of the learning process and its deep analysis, together with its pedagogical implications is what this study intends to accomplish.

Theoretical framework

Communicative Language Teaching

Communicative Language Teaching (CLT), one of the currently most widely accepted approaches to language teaching around the world has been defined and explained by many authors in the last four decades.4 This present work will consider Brown’s description of its objectives, which says that CLT is “an approach to language teaching methodology that emphasizes authenticity, interaction, student-centered learning, task based activities, and communication for the real world, [with] meaningful purposes”.5

Also, as its names implies, CLT has its roots in “communication”. The problem is that this concept has sometimes been misunderstood. After the decline of the Audiolingual Method (early 1960s), a deeply rooted behavioristic approach, it became clear that students needed to be given a more central role and that a reduction of teacher talk was essential to achieve that intended goal. Therefore, teachers simply “got students to talk”, especially through pair or group work. However, this increase in student-talk did not mean that learners actually communicated with each other since the activities were highly controlled. Even today, the crux of the matter is still present: many teachers believe that “talking” and “communicating” mean the same, when, in fact there is a world of difference between the two terms. The former simply revolves around the repetition of vocabulary or target structures and drill work. The latter, on the other hand, involves the learners in real exchanges of information, where they will give their opinions, ask for and answer about unknown data, etc.

Genuine communication, as CLT understands it, happens when interlocutors have a desire and a purpose for communication, when there is a focus on content and when there is no control whatsoever by the teacher or the materials.6 This idea goes hand in hand with the main objective that the approach has: to teach “communicative competence”, or the ability to use the language correctly and appropriately to accomplish communication goals.

To summarize, it may be said that CLT projects an ideal classroom where students have a predominant role and where meaningful interaction among its members is fostered. In order to create a learner-centered class, the role of the teacher must be that of a facilitator and monitor. In turn, learners become the active participants who have a greater degree of responsibility for their own learning. Cooperation with their classmates is crucial in this environment since students have to “become comfortable with listening to their peers in group work or pair work tasks, rather than relying on the teacher for a model”.7 Meaningful interaction is achieved through different activity-types that foster fluency such as those that “reflect natural use of language, focus on achieving communication, require meaningful use of language and communication strategies, produce language that may not be predictable, and seek to link language use in context”.8 Nevertheless, CLT advises teachers not to neglect accuracy activities, and to use these ones, especially to support fluency tasks.

At this point it should be mentioned that the English as a Foreign Language Teaching Program (EFLTP) at Universidad Adventista del Plata (UAP) can be considered a CLT advocate. Apart from the fact that most faculty members personally use this method in their classes, the specific teaching training subjects (“EFL Pedagogy” and “EFL Teaching Practicum” make use of its theory as well. Teacher trainers at this institution consider that within the wide variety of modern approaches to language teaching –some of which are eclectic in nature and are a combination of different methodologies– CLT is, so far, the most practical and efficient approach.

Classroom observation

Educational research in the 20th century was carried out at a time when the “recitation” lesson was the standard, formal way of presenting information. Back then, the focus of observation revolved around attentiveness. Observers would sit at the front of the classroom and scrutinize faces to see how many students were paying attention. Then, a correlation with the activities, the content matter, scores, etc., was established to set patterns and to describe what was effective teaching and what was not. Even when these studies were somewhat “crude”, they were the basis for later work. Soon enough, researchers came to understand that talk was a vital part of classroom life, so a shift took place and studies began to concentrate on what teachers and students said to each other.9

The history of research shows that classrooms have been observed under the influence of one or more of the following four traditions: psychometrics, ethnography, discourse analysis, and interaction analysis, being the last one the selected for this study.

Interaction

“Interaction is the collaborative exchange of thoughts, feelings, or ideas between two or more people, resulting in a reciprocal effect of each other”.10 It goes without saying that meaningful social interaction is essential for the learner to develop his/her interlanguage. Pica expands this point by saying that

on the basis of extensive research, there is now considerable agreement that the learning environment must include opportunities for learners to engage in meaningful social interactions with users of the second language if they are to discover the linguistic and sociolinguistic rules necessary for second language comprehension and production.11

However, and in spite of the general agreement among researchers that interaction is vital for language development, there is still disagreement on how it really influences and conditions second language (L2) development.

On one end of the continuum we find Steven Krashen’s position. Mainly throughout the 1980s and 90s, he proposed, extended and revised his Input Hypothesis,12 which claims that for language learning to take place, there is only one sole condition needed: availability of comprehensible input. This term, coined by Krashen himself “is defined as second language input just beyond the learner’s current second language competence, in terms of its syntactic complexity”.13 What this theory suggests, then, is that when learners ask their interlocutors’ assistance to understand what is being said, a restructure of the interaction between them happens so that unfamiliar linguistic material can be made clear. According to this belief, “such understanding is the foremost step towards incorporating the new linguistic material into the learner’s emerging L2 system”.14

In the early 1980s, another researcher, Michael Long, focused his attention on the kinds of interactions in which learners got involved and put forward his “Interaction Hypothesis”.15 For him, interaction includes an element that can completely transform the nature and quality of input: “negotiation of meaning,” whose main purpose is to reach mutual understanding between the interlocutors. According to Lightbown and Spada, “negotiation of meaning is accomplished through a variety of modifications that naturally arise in interaction, such as requests for clarification or confirmation, repetition with a questioning intonation, etc”.16 In this sense, every time students ask questions to clarify meaning, paraphrase or rephrase information, input becomes meaningful for them because it responds to their own particular developmental needs.

On the opposite end of the continuum lies Merrill Swain’s Output Hypothesis,17 with its recognition to the value of input but with its affirmation that exposure to a language alone will not do the trick. Her claims point to the notion that “only second language production (i.e. output) really forces learners to undertake complete grammatical processing, and thus drives forward most efficiently the development of second language syntax and morphology”.18

Verbal interaction

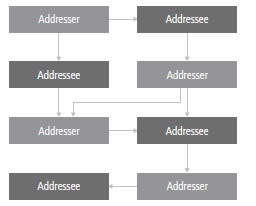

[V]erbal interaction is a continuous, shifting process in which the context and its constituent factors change from second to second. (…) The addresser of one minute is the addressee of the next, and vice versa. Purpose and content change as the interaction progresses.19

The diagram that appears below helps exemplify the process of normal, casual conversation between two people. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1. The flow of verbal interaction.

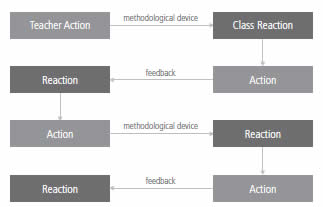

When pedagogic interaction (i.e. the interaction of teaching and learning) happens between a teacher and his/her class, the pattern is composed of a chained set of action-reaction events. In this process, the teacher is constantly monitoring students’ reactions to adjust his/her next action. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2. The flow of pedagogic interaction.

Malamah-Thomas concludes that “the learning event parallels the speech event. Pedagogic interaction parallels verbal interaction. Teaching acts can parallel speech acts”.20

Interaction analysis

Interaction analysis developed in the 1970s, and had its origin with Flanders’ ten categories of description for classroom verbal behavior. Throughout time, many other authors have created their own instruments, most of which are basically adaptations, extensions or simplifications of those ten categories. Some of the most relevant will be briefly described below.

FIAC

Designed by Ned Flanders, the Flanders Interaction Analysis Categories21 analyzes verbal interaction between teachers and pupils with the aim of seeing what it can reveal about the teaching and learning processes. The ten categories have been devised to consider “teacher talk”, “pupil talk” and “silence”. Within the first category, the items are: “accepts feelings”, “praises or encourages”, “accepts or uses ideas of pupils”, “asks questions”, “lectures”, “gives directions” and “criticizes or justifies authority”. The second category, much shorter than the first, evaluates the pupils’ acts as either responding to or initiating interaction. Silence (or confusion) is also accounted for.

Even when this instrument was created to be used in first language educational research, it became the basis for future observation tools. With it, the interaction analysis tradition was established.

FLINT

Moskowitz took FIAC and made adaptations and additions that, to her mind, would be more relevant for language classrooms. This model, called Foreign Language Interaction,22 contains 22 items. The objectives of this scheme are basically three: to identify what is “good” language teaching, to provide feedback to trainee-teachers, and to label a classroom as teacher or student-centered.

The two categories are the same as those in FIAC: “teacher talk” and “student talk”. Silent moments are only recorded within the last category. Now, “teacher talk” is subdivided into two subcategories: “indirect influence” (which includes items such as “deals with feelings” or “asks cultural questions”) and “direct influence” (among whose elements one can find: “gives information”, “corrects without rejection”, “criticizes student behavior” or “personalizes about self ”). Regarding the second category, student talk is evaluated and analyzed considering issues like “reads orally”, “choral”, “specific”, “confusion”, and “laugher”, among others.

FOCUS

Another taxonomy is the one proposed by Fanselow. Its title, Foci for Observing Communications Used in Settings,23 is self-explanatory and does not limit its use to classroom behavior. In fact, this model can be used to observe any kind of human interaction, regardless of the setting where it occurs. Therefore, the categories of this model (listed below) do not differentiate teachers and students. Simply, the categories apply to whoever is speaking at a given time.

- Who communicates?

- What is the pedagogical purpose of communication?

- What mediums are used to communicate?

- How are the mediums used to communicate areas of content?

- What areas of content are communicated?

COLT

More student-centered than its predecessors, the observation scheme Communicative Orientation of Language Teaching24 was designed by Allen, Fröhlich and Spada in 1984. What this large-scale evaluation of CLT tries to establish is the relation between the methodologies used in an L2 classroom and their learning outcomes. This instrument is divided into two parts, the first of which describes process that occur in the classroom, and is coded in real time. The second part uses the audio recordings to analyze verbal interaction between teachers and students.

TALOS

The observation system known as Target Language Observation Scheme,25 created by Ullman and Geva, is another tool used to observe classroom behavior. Because this instrument is the one that has been selected to carry out the present research study, full details will be given in the following section.

Methodology

Aims of the study

This research project is descriptive and correlational in nature, and was conducted at the Universidad Adventista del Plata, in Libertador San Martín, Entre Ríos, Argentina. A private institution, UAP offers undergraduate, graduate and postgraduate degrees and its students come from more than 50 countries around the world.

The study pretends to describe the pedagogical, oral interaction that occurs between teachers and students, and among students in the classrooms of the EFLTP at UAP. As it was mentioned earlier, oral interaction with a pedagogical function can show a lot about the way teachers and students view language and understand its acquisition and learning. The English Teaching program at UAP believes that the tenets that CLT proposes are solid and meaningful enough to help learners in those processes and in becoming competent language professionals.

The specific objectives are the following:

- To observe the pedagogical, oral interaction that occurs among the participants of the subjects “English Language” in each of the five years of the program.

- To describe the types of interaction that occur in the aforementioned classrooms.

- To analyze the communication strategies used by teachers and students.

- To compare the classes observed with the CLT paradigm to establish the pedagogical implications of what happens in those classrooms in the teaching and learning processes.

- To draw conclusions that may lead to a better understanding of the current situation of the EFLTP at UAP, and which may function as a stepping-stone for improvement.

Limitations of the study

Although this research was carefully prepared and it reached its aims, it certainly has some limitations, which will be detailed below.

The first limitation is related to the sample size. Even though the amount of classes observed is significant for the EFLTP, the results obtained may not be applied to other learning contexts, especially when groups of students are bigger. The way students and teachers interact in small classes such as the ones under observation can be very different from the kind of oral interaction that takes place among members of a larger group. In the latter, factors such as shyness or little acquaintance with peers may negatively affect participation, for example.

A second aspect that has not been considered by this research paper is that of gender differences. It is common knowledge that men and women communicate differently. Their conversational styles differ, for instance, on the grounds of same-sex or opposite-sex interaction. The issue of gender is a deep one and due to time and resource restrictions, it will not be addressed here.

Cultural bias is another limitation that this study has. As it was previously stated, students at UAP come from many different countries, which means that their behavior in the classroom and the relationships among classmates and teachers can be significantly different. This, in turn, could have an effect on the way face-to-face interactions occur. Interesting as these differences may be, they do not constitute the main focus of this work and, consequently, have been excluded from it.

The last limitation is a factor that cannot be considered at its fullest by this investigation and refers to the direct correlation between students’ level of attainment and oral interaction in the classroom. Even though some general inferences have been made from the analysis carried out, the observation scheme chosen for this study does not contemplate level of attainment as a determining factor in classroom interaction. This means that the five classes observed, which show a progressive mastery of the language, will be the only account on this sense.

Participants

The subjects of study are students and teachers of the EFLTP, which belongs to the School of Humanities, Education and Social Sciences at UAP. Entry and exit levels are determined by placement tests at the beginning of the program, and different language examinations throughout and at the end of it. The scale used for this paper is the standardized level reference created by the Council of Europe, called Common European Framework Reference (CEFR).26 Upon their arrival, students’ level is a fair B1. After the 5-year course, they attain a C2, which shows an advanced command of the language. Students’ ages range from 18 to 23 years old, and in the classes, there is a clear female predominance: out of the 47 students in the classes observed, only 11 (21%) are male. Regarding teachers, their experience goes from 5 to 20 years of working in the field. Some of them have postgraduate degrees, some are pursuing one and others have a first degree. With reference to gender, the female-male relationship is 4 to 1.

The classes to be observed were carefully selected. Among the many subjects in the curriculum, some teach English and others, about English. For example –and very broadly speaking– in a class such as “English Language” students are trained to develop their communicative skills, and its ultimate goal is to learn the language. On the other hand, classes such as “English Grammar” or “Phonetics” aim at teaching students about the language rather than using the system itself. In the first case, English learning is the end; in the second, it is the means. Therefore, the classes that would best suit the needs of this project and would provide its most suitable environments were the different “English Language” classes.

Each of the five academic years of the EFLTP has a subject called “English Language”, which is divided in two parts (one part in each semester). Because this project was carried out in the second part of the year, the classes selected were the following:

- English Language II (EL II) – first year

- English Language IV (EL IV) – second year

- English Language VI (EL VI) – third year

- English Language VIII (EL VIII) – fourth year

- English Language X (EL X) – fifth year

Additional information relates to the number of students per class and the general level of attainment students have in each course.

- EL II: 13 students; level of attainment: B2

- EL IV: 14 students; level of attainment: B2+

- EL VI: 11 students; level of attainment: C1

- EL VIII: 11 students; level of attainment: C1+

- EL X: 8 students; level of attainment: C2

Data collection instrument

As it was introduced earlier, the instrument chosen for this study is Ullman and Geva’s Target Language Observation Scheme (TALOS). The strongest reason for this choice is that its aims perfectly fit the objectives of this work; TALOS was “developed to reflect on aspects of second language program implementation that previous research had suggested to be important and (…) designed for the purposes of formative program evaluation”.27 This instrument, created to observe live classroom activity, contains two sections which code the same classroom events differently. One of the advantages of such a system is that it “should be possible to check the validity of the categories as representing theoretical constructs observable in second language classroom practice”.28

“The coding categories of the first section of this scheme have been defined by their authors as low inference, meaning that they are clearly described and should be easy for persons using the instrument to identify in actual classroom behavior”.29 In order to obtain the information, the observer is to check the corresponding categories as occurring during a 30-second time, which is followed by a 90-second period where he/she does not record anything at all and freely observes the flow of the class. Each of these 30-second periods is called a unit. The aim of this section is to categorize observable events such as the linguistic and substantive content being taught, the language skill developed and the teaching strategies in use in the foreign language classroom.

The second part of the instrument (high-inference in nature – tends to be more subjective) is to be completed at the end of the observation. Its categories have to be rated in an ordinal scale (which goes from “extremely low” to “extremely high”). Basically, this part of TALOS elicits information about teachers and students’ involvement in the class.

Definition of constructs

The categories contained in TALOS have been glossed by its authors. The teacher part of the low-inference TALOS describes all behavior directed and initiated by the teacher. It is subdivided into the following categories:

- To whom reflects who is being addressed by the teacher on a continuum from large to individuals.

- What-type of activity refers to classroom activities initiated by the teacher to achieve pedagogical goals. These activities are arranged on a continuum from formal to functional, beginning at the formal end with drill and ending with the most open-ended activity free communication.

- Content focus is subdivided into linguistic content and substantive content. By linguistic content we refer to the emphasis on the formal properties of the L2, namely sound, word, phrase or discourse. By substantive content we refer to overt formal grammar teaching, the explicit development of cultural information during the lesson and the introduction and integration of other subject matter into the second language program.

- Skill focus describes the listening, speaking, reading and writing skills practiced in each lesson segment. The skill focus category makes clear the skill- building intent and purposes of each activity and each teaching act undertaken by the teacher.

- Teaching medium refers to those heuristic devices which the teacher uses in order to develop the formal or functional focus of the lesson, the substantive content in the lesson or the skill-building intent of the activity.

- Teaching act refers to pedagogical verbal strategies used by the teacher to enhance learning in the students such as teaching acts that are directly related to the lesson at hand, e.g., explain and correct as well as teaching acts which relate to classroom management, e.g., routine and discipline.

- Language use relates to the crosslingual-intralingual continuum and describes the language used in the classroom by students and teachers. It provides information about the relative amount of L1 and L2 used, and in conjunction with other activities, it provides information about the circumstances under which each language is being used.30

The “student” part of the low-inference section makes reference to student-initiated behavior and in addition to the To whom and Language use described above, this section includes a category for type of student response or question:

- What-type of utterance deals with the individual student responses to teacher-initiated prompts. The entries in this category may be either verbal or non-verbal. The verbal responses are arranged on an utterance size continuum starting with a single sound and ending with extended discourse. A “no response” entry is also included in this category.

- Type of question describes student-initiated questions, e.g., cognitive questions and questions relating to classroom management and routines.31

The high-inference section summarizes the major characteristics of the second language classroom which relate to teachers, students and program. In the “teacher” part, the following broad dimensions are found: L2 use and L1 use, teacher intent and purposefulness (e.g., clarity); teaching strategies (e.g., personalized comments, gestures) and teacher traits (such as humor, enthusiasm). The “student” part rates use of L1 and L2 on task; student activity (e.g., initiates personalized questions and comments) and student interest (e.g., attention). Under the heading “program”, items such as linguistic appropriateness, content appropriateness, variety, listening focus, speaking focus, reading focus, writing focus, etc.).

Data collection and data analysis

The information needed for this project was collected through the classroom observation instrument TALOS. Each of the five classes chosen for the study was observed for 40 minutes. Therefore, this project obtained information based on the following:

- Low-inference section: 300 units of analysis (60 per class)

- High-inference section: 27 items for analysis per class

Before the classes were observed, all the teachers were adequately informed about the project and were asked for their permission to be observed and audio-recorded with their students. They were also told that they should not do anything different in their classes to fit in any way what they considered could be the parameters of observation. Besides, it was clearly specified that in order to avoid changes in behavior or some sort of conditioning, students were not to be briefed about the investigation. The five teachers accepted the terms and signed a document expressing their agreement with the project.

The standard procedure took place as follows: I arrived to the each of the classrooms during break-time so as not to interrupt the class. Once in, I would greet the teacher, put the recording device in place, and find a seat at the back of the room but in a location from which I could see everything that went on. During the 40-minute observation, I took notes as a reminder of some of the events of the class. This, in combination with the audio, served as the raw material to be recorded in the observation matrix.

After the information was gathered, it was entered for its quantification and study in a program for statistical analysis called Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), English version 20.0. The data analysis included frequencies, percentages and mode. Expressed differently, the first two mea suring techniques indicate how often a particular event occurs. Meanwhile, the mode specifies the average score in a given distribution.

Results and conclusions

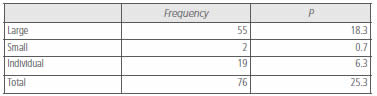

The global analysis of the five classrooms observed shows that teacher talk-time and that of their students was quite balanced, favoring the learners, who had a greater chance to interact with the other subjects in the class. In the time-units analyzed (N=300), the teacher initiated oral interaction 76 times (25.3%), using only the L2. The students spoke 105 times (35%) in the same period, using English on 93 occasions (88.6%). In the remaining time (39.7%), the class as a whole was silent. This particular data clearly portrays classrooms where learner-centeredness is fostered. There were no significant differences in teacher and students talking time when the analysis was done in each individual class. For example, in English Language II, the teacher’s talking time was 17%; in English Language IV, 18%; in English Language VI, that average was 23%; in English Language VIII, it was 20% and in English Language X, the teacher spoke 21% of the time.

The fact that the teacher is not the focal point of the class has great implications in language teaching pedagogy. In all the classes of the EFLTP, students were given ample room to express themselves and to speak freely. However, the results indicate that learners found it hard to initiate interaction. Theories of second language acquisition suggest that students whose roles in the classrooms are more active tend to learn better. All in all, from the general results obtained by this study in this aspect, it may be said that the classes observed provided an enriching environment for learning.

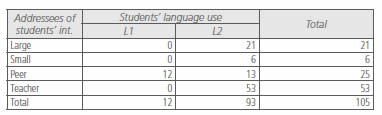

Teacher’s interaction

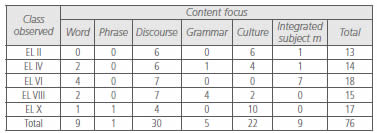

As it was mentioned before, the teachers initiated some form of oral interaction with their students 25.3% of the time (f=76), speaking mostly to the class as a whole (large). The Table 1 provides information on the addressees of those interactions. Given the fact that many tasks were planned for students to work in pairs or threes, there were, surprisingly, only two instances where teachers directed their speech to these small groups (small).

Table 1. Teacher’s interaction – to whom

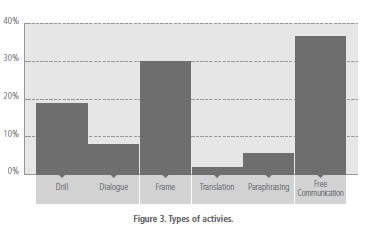

Regarding the types of activities (Figure 3), it can be said that most of the time, students and teachers alike were engaged in free communication. By no means does this portray disorganized classrooms without clear pedagogic aims. On the contrary, the contexts for free communication were clearly planned by the teachers and were the natural outcome of more controlled activities that had been started earlier. Frame activities, which are those situated in the middle of the “controlled vs. free activities continuum”, occurred 28.9% of the time.

Figure 3. Types of activies.

Drills were the third most frequent activity carried out in the classrooms observed. This is a very interesting fact, having in mind that CLT has neglected the very nature of this type of task for it does not motivate students to communicate, nor does it provide a meaningful purpose for interaction, two factors that are considered essential to foster students’ autonomy.

The type of activity with the lowest frequency (f=1) was translation. The activity in itself was very short (less than five minutes); students were asked to use some colloquial language in different situations and then to think of ways in which those sentences could be expressed in their L1. Possibly, in the teachers’ minds the term still carries a negative connotation. It should be remembered that the strongest versions of CLT ban all forms of translations from the foreign language classrooms.

Another item analyzed was related to the content focus that each teacher-initiated interaction had. Out of the 76 times that teachers spoke, 30 (39.5%) were connected to discourse. This has considerable implications in language pedagogy because it is vital for learners to be aware of the numerous ways language is used in different situations. And this is connected to learning language functions. According to Harmer, students “need to know the difference between formal and informal language use. They need to know when they can get away with ‘sorry’ and when it would be better to say ‘I really must apologize’, for example”.32

Culture was the second most frequent category (28.9%). It goes without saying that language is a culture-bound phenomenon and nowadays teachers have begun to recognize the students’ need and desire to develop sociocultural competence. The implications that teaching culture has in the learning process are tremendous. According Andrade et al., there are

conventions ruling any communicative act, either written or spoken. Awareness of these cultural conventions can smooth communication. At the same time, a positive, co-operative attitude on the part of the listener/reader can help guard against ignoring, forgetting or flouting these conventions.33

The content focus items that occurred less frequently were those related to grammar and language study at the phrase level (f= 5 and 1 respectively), which is in agreement with the information presented earlier in relation to discourse. It is now widely recognized that effective learning occurs when language is presented in context, and that language study from functions is more effective than that which focuses entirely on forms. Referring to materials, the following quote from Lightbown and Spada can also be applied to activities. They affirm that

when a particular form is introduced for the first time, or when the teacher feels there is a need for correction of a persistent problem, it is appropriate to use narrow-focus materials that isolate one element (….) but it would be a disservice to students to use such materials exclusively or even predominantly.34

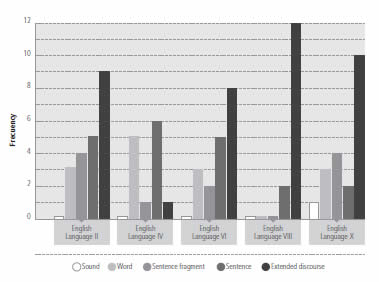

The information displayed in Table 2 shows how the different activities were distributed per class, but nothing in it suggests a particular pattern. What can only be highlighted is that in relation to content focus, EL II is the class with the most variety: there is a focus on all types of content but at the level of phrase.

Table 2. Cross tabulation between classes observed and content focus.

Given the importance of a well-balanced program in relation to skill teaching, finding that most of the classes observed were unbalanced was, at least, worrying. On average, when there was oral interaction, the teachers directed their classes to listening practice only 3.9% of the time; another 14.5% was dedicated to writing activities: 23.7% was used for students to read; and in the remaining 57.9%, students were engaged in speaking tasks. When each class was studied individually, the same marked emphasis on speaking was identified. On the other hand, on the observed days, two classes (EL IV and EL VI) out of the five included some listening practice and three of them (EL IV, EL VI and EL VIII) had their students do some writing tasks.

Regarding the teaching medium, TALOS includes in its categories the following items: text, audio-visuals, authentic materials, draw, poem, song, and role playing, but only the first three were used by the teachers observed, being the text the type of material used most frequently (f=36). On the other situations where there was oral interaction taking place, the teachers used no materials at all (f=30), especially when their students were engaged in speaking tasks. Audio-visual aids, all of them in the form of pictures and posters, were used an average of 10,5% of the time (f=8).

Another aspect that deserves attention is that of authentic materials (i.e. produced specifically for native speakers, and not for language learners). In fact, what needs attention is the poor use of them (2.6%). Of course, this makes sense if the reader has in mind that these kinds of materials are used mainly for reading and listening tasks, which were, as mentioned earlier, not fully developed in the classes under observation. According to Harmer, one of the most well-known referents to CLT, non-authentic materials are useful when teaching structures but useless when teaching reading or listening skills.35 It could be argued, then, that the English Language classes at UAP do not take the full advantage that authentic materials have to offer.

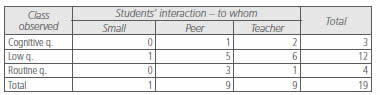

Teaching acts are varied and numerous. When teachers initiated oral interaction in their classes, they had the following main objectives: 44.3% to ask cognitive questions (f=33); 18.4% to explain (f=14); or 11.8% to ask low-level questions (f=9). On a more infrequent basis, teachers used the rest of their talk time narrating, discussing issues, reinforcing their students, making meta-comments and answering students’ questions (see Table 3 for full details discriminated by class).

Table 3. Cross tabulation between classes observed and teaching acts.

Students’ interaction

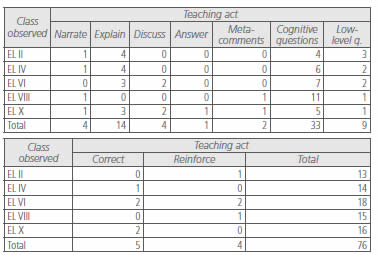

In the different subjects observed, students interacted at different stages with all the other members of the class. Of all their oral exchanges (n=105), students seldom interacted in small groups (f=6), but they did so much more repeatedly in pairs (to a peer). Seven per cent of their talk time was used in speaking to the class as a whole (large). However, students directed most of their speech to their teachers (f=53). (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4. Addresses of students’ interaction.

The cross tabulation between each of the classes observed and the students’ interaction show the same tendencies. For example, out of the 53 times that students interacted directly with their teachers, 10 times occurred in EL II; another 10 times in EL IV; 11 in EL VI; 7 in ELVII; and 15 in EL X.

Before continuing, the reader must remember that the types of students’ oral interaction are recorded by TALOS in two different categories: What-type of utterance deals with the individual student responses to teacher-initiated prompts and Type of question describes student-initiated questions, either to the teacher or to the peers.

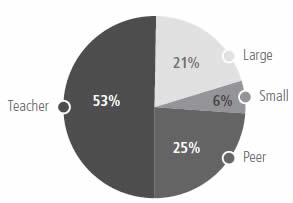

Having said that, the mode in the variable type of utterance indicates that extended discourse was the most frequently occurring category (f=40) and its distribution in the individual classes was rather constant (see figure 5). Then, it is not surprising to see that the least frequent category was that of sound (f=1). All this may be explained by the priority seen on fluency (see table 3 to check the frequency of correction). The categories word, sentence and sentence fragment had overall frequencies of 14, 20 and 11 respectively. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5. Distribution of students’ type of utterances per class observed.

It is interesting to note that students never addressed their teachers using their L1. They used Spanish only on some of the occasions when they interacted with a peer. This corresponds to the ideal classroom that CLT proposes, where the native language (L1) does not occur (or occurs infrequently and under certain controlled circumstances). The CLT paradigm suggests that teachers are to discourage the use of the L1 during oral communicative activity. However, if working in pairs to compare answers to a reading comprehension exercise or some vocabulary-matching practice, the occasional use of the mother tongue should not worry teachers. Another remarkable detail shows that the students’ use of their mother tongue tended to decrease in the last years of study. (See Table 4.)

Table 4. Cross tabulation between addressees of students’ interaction and language use.

Students’ oral interaction was much higher when it was teacher-initiated (86 times out of 105). This might suggest that learners need to be trained to feel more comfortable to ask questions. The types of questions that students asked more commonly were the low-level questions (63.2%). On average, routine questions occurred 21.1% and cognitive questions scored the lowest: 15.8% (which came up in EL IV and EL VI). Considering the tendency for cognitive questions to rise toward the last years of the program, one would expect that the frequency of these questions would have been higher. Table 5 indicates who were the addressees of students’ different types of questions.

Table 5. Cross tabulation between students’ type of questions and addresses.

Final considerations

In relation to the positive features that this study revealed, it may be said that the different EL classes provided meaningful contexts for students to develop their language skills. Moreover, the teachers were able to create relaxed environments that cater for opportunities for learners to take active roles. Interactions among the members of the classes had clear pedagogic aims, and students were guided to see them so that they become more aware of their own learning. Genuine communication was part and parcel of the subjects taught.

Another distinct advantage relates to teacher talk-time and students talk-time, which showed to be quite balanced. In the moments of oral interaction, there was a clear tendency to move to less controlled activities, which gave the learners a sense of responsibility and true purposes to communicate. As a result, students appeared to be motivated, a feature highly valued by CLT.

Statistical information indicated that there was a preponderant content focus at the level of discourse. Even when it could be argued that a global perspective on language study may lack essential elements necessary for students’ accuracy, there is general consensus over the importance that this strategy has in the overall learner’ development.

Considering the growing importance given to the explicit teaching of cultural issues in the classrooms, it should be pointed out that English Language classes throughout the program devoted a fair amount of time to its analysis and debate. Our world needs citizens who appreciate diversity. By providing instances where students can be informed about other people’s cultures and form an opinion on them, the EL classes are helping learners become competent users of the language in the broadest sense of the concept.

Last but not least, students must be given credit for the high frequency of L2 use and for a good command of the language, shown especially through extended discourse. Regarding the latter, it is important to highlight the fact that extended discourse on the part of the students was present even in the lowest-level class (EL II).

However, there are some aspects that could be improved. To start with, skills should be given a more balanced emphasis. Listening and writing occurred much less frequently than speaking and reading. Further research could investigate on the reasons why this situation may happen, and based on the results, suggest an appropriate course of action. At this point, suffice it to say that a class that places more importance on certain skills at the expense of others needs to revisit its objectives in order to ensure that students can be trained in language use as it occurs outside the classroom.

On a different matter, the treatment of errors and the sometimes marked emphasis on fluency should be revised. Corrective feedback (CF) is a controversial topic. Ellis believes that the controversies around it are basically five, them being

(1) whether CF contributes to L2 acquisition, (2) which errors should be corrected, (3) who should do the correcting (the teacher or the learner himself/herself), (4) which type of CF is the most effective, and (5) what is the best timing for CF (immediate of delayed).36

Second language acquisition literature has produced the most varied answers to these questions. It is no wonder, then, that teachers sometimes find themselves in a predicament, and this may, at least partially, explain why most of them use but very few correction techniques during oral interaction. Even when CLT aims at developing fluency, it assures that accuracy is not to be overlooked. However, EL classes have fallen short in this aspect. It is true that there were instances of accuracy practice, but students were hardly ever corrected when they spoke in less controlled instances and made mistakes. There are many techniques to provide CF, such as guiding the learner through self-correction or providing him/her with the correct structure. In any case, it is clear that improvements in this area could be made.

It was pointed out previously that learners were given ample room for participation. Yet, they engaged more easily in oral interaction when the teacher took the lead, but found it hard to initiate interaction themselves. Being aware of this fact, teachers may want to discuss this situation with their students in order to identify the reason why this happens and find ways to boost student-initiated participation.

Another aspect worth analyzing is that of teaching resources. Among the wide variety available to teachers, authentic materials could have a more preponderant presence in the classes. Access to these kinds of materials has been made easy by the Internet, and it should be remembered that authenticity is a core component of CLT. Consequently, teachers should take full advantage of such materials if they want to bring “the real world” into the classroom.

At the beginning of this paper there is a quote from Brown which describes the objectives that CLT promotes, those being an emphasis on authenticity, interaction, student-centeredness, tasks, and communication that has meaningful purposes and which prepares students for the real world. After the thorough analysis carried out, and considering its focal point, the general conclusion drawn is that each of the classes observed are very close to the aforementioned definition.

1 Craig Chaudron, Second Language Classrooms: Research on teaching and learning (Melbourne: Cambridge, 1988), 1. [ Links ]

2 Ibid.

3 Ann Malamah-Thomas, Classroom Interaction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), viii. [ Links ]

4 Some of these authors are H. Douglas Brown, Teaching by Principles (New York: Addison Wesley Longman, 2007); [ Links ] Jeremy Harmer, The Practice of English Language Teaching, 4th ed. (Essex: Longman, 2007); [ Links ] Patsy M. Lightbown and Nina Spada, How Languages are Learned, 3rd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006); [ Links ] Jack Richards y Theodore Rogers, Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching: a description and analysis, 3rd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014). [ Links ]

5 Brown, Teaching by Principles, 378.

6 Harmer, The Practice of English Language Teaching.

7 Jack C. Richards, “The official website of linguist Dr Jack C Richards”, available at: http://www.professorjackrichards.com/wp-content/uploads/communicative-language-teaching-today-v2.pdf; Internet (accessed November 7, 2014), 5.

8 Ibid, 14.

9 Eduard Conrad Wragg, An Introduction to Classroom Observation, Classic edition (London: Routledge, 2012). [ Links ]

10 Brown, Teaching by Principles, 165.

11 Teresa Pica, “Second-Language Acquisition, Social Interaction, and the Classroom”, Applied Linguistics 8, nº 1 (1987): 4.

12 Stephen Krashen, Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition (Los Angeles: University of Souther California, 2009), available at: http://www.sdkrashen.com/content/books/principles_and_practice.pdf; Internet (accessed December 4, 2014). [ Links ]

13 Rosamond Mitchell and Florence Myles, Second Language Learning Theories, 2nd edition (London: Hodder Arnold, 2004), 47. [ Links ]

14 Pica, “Second-Language Acquisition”, 6.

15 Michael Long, “Input, Interaction and Second-Language Acquisition,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 379 (1981): 259-278.

16 Lightbown and Spada, How Languages are Learned, 150.

17 Swain’s hypothesis has been presented in many of her writings, the most important of which are Swain, 1985 and Swain, 2000.

18 Mitchell and Myles, Second Language Learning Theories, 1.

19 Malamah-Thomas, Classroom Interaction, 37.

20 Malamah-Thomas, Classroom Interaction, 37.

21 Ned A. Flanders, Analyzing Teaching Behavior (Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley, 1970). [ Links ]

22 Gertrude Moskowitz, “The Classroom Interaction of Outstanding Language Teachers,” Foreign Language Annals 9, nº 2 (1976): 135-143.

23 John F Fanselow, “Beyond Rashomon: conceptualizing and describing the teaching act,” TESOL Quarterly 11 (1977): 17-39.

24 J. Patrick Allen, Maria Fröhlich, and Nina Spada, “The communicative orientation of language teaching”, in TESOL’83, eds. J. Handscombe, R. Orem and B. Taylor (Washington, DC: TESOL, n.d.).

25 Rebecca Ullmann and Esther Geva, “Approaches to observation in second language classrooms,” in Language issues and education policies: exploring Canada’s multilingual resources, Patrick Allen and Merrill Swain, eds., 113-123 (Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1984).

26 The complete framework can be found in the official site of the Council of Europe (http://www.coe.int/t/dg4/linguistic/cadre1_en.asp).

27 Brian K. Lynch, Language Program Evaluation: Theory and Practice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 110. [ Links ]

28 Ullman and Geva, “Approaches to observation in second language classrooms,” 118, 119.

29 Lynch, Language Program Evaluation, 110.

30 Ullman and Geva, “Approaches to observation in second language classrooms,” 120, 121.

31 Ullman and Geva, “Approaches to observation in second language classrooms,” 120, 121.

32 Harmer, The Practice of English Language Teaching, 343.

33 Mercé Bernaus Anna Isabel Andrade, Martine Kervan, Anna Murkowska, y Fernando Trujillo Sáez, eds, Plurilingual and Pluricultural Awareness in Language Teacher Education: a Training Kit (Strasbourg, Council of Europe Publishing, 2007), 14; available at: http://archive.ecml.at/mtp2/publications/B2_LEA_E_internet.pdf; Internet (accessed August 1, 2014). [ Links ]

34 Lightbown and Spada, How Languages are Learned, 191.

35 Harmer, The Practice of English Language Teaching.

36 Rod Ellis, “Corrective Feedback and Teacher Development”, L2 Journal 1 (2009): 3, available at: http://www.escholarship.org/uc/item/2504d6w3; Internet (accessed November 10, 2014).