Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Acta Odontológica Latinoamericana

versão On-line ISSN 1852-4834

Acta odontol. latinoam. vol.23 no.3 Buenos Aires dez. 2010

ARTÍCULOS ORIGINALES

Relationship between psychological factors and symptoms of TMD in university undergraduate students

Aldiéris A. Pesqueira, Paulo R. J. Zuim, Douglas R. Monteiro, Paula Do Prado Ribeiro, Alicio R. Garcia

Department of Dental Materials and Prosthodontics, Araçatuba Dental School, São Paulo State University, SP, Brazil.

CORRESPONDENCE Aldieris Alves Pesqueira Department of Dental Materials and Prosthodontics Aracatuba Dental School, Sao Paulo State University Jose Bonifacio, 1193, Aracatuba, SP, Brazil 16015-050 E-mail: aldiodonto@uol.com.br

ABSTRACT

Temporomandibular disorders is a collective term used to describe a number of related disorders involving the temporomandibular joints, masticatory muscles and occlusion with common symptoms such as pain, restricted movement, muscle tenderness and intermittent joint sounds. The multifactorial TMD etiology is related to emotional tension, occlusal interferences, tooth loss, postural deviation, masticatory muscular dysfunction, internal and external changes in TMJ structure and the various associations of these factors. The aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of the relationship between signs of psychological distress and temporomandibular disorder in university students. A total 150 volunteers participated in this study. They attended different courses in the field of human science at one public university and four private universities. TMD was assessed by the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) questionnaire. Anxiety was measured by means of a self-evaluative questionnaire, Spielberger’s Trait-State anxiety inventory, to evaluate students’ state and trait anxiety. The results of the two questionnaires were compared to determine the relationship between anxiety levels and severity degrees of chronic TMD pain by means of the chi-square test. The significance level was set at 5%. The statistical analysis showed that the TMD degree has a positive association with state-anxiety (p=0.008; p<0.05) and negative with trait-anxiety (p=0.619; p<0.05). Moreover, a high TMD rate was observed among the students (40%). This study concluded that there is a positive association between TMD and anxiety.

Key words: Temporomandibular joint disorders; Epidemiology; Questionnaires; Prevalence; Anxiety; Depression.

RESUMO

Relação entre fatores psicológicos e sintomas de DTM em estudantes universitários

Disfuncao temporomandibular e o termo usado para descrever uma serie de disturbios envolvendo as articulacoes temporomandibulares, musculos da mastigacao e oclusao, com sintomas comuns como dor, restricao de movimento, sensibilidade muscular e ruido articular intermitente. A etiologia da DTM e multifatorial e esta relacionada a tensao emocional, interferencias oclusais, perda de dentes, desvio postural, disfuncao muscular mastigatoria, mudancas internas e externas na estrutura da ATM, e a diferentes associacoes entre esses fatores. O objetivo deste estudo foi avaliar a relacao entre estresse psicologico e sinais de desordem temporomandibular em estudantes universitarios. Um total de 150 voluntarios participaram deste estudo sendo alunos de uma universidade publica e quatro universidades privadas de diferentes cursos da area de ciencias humanas. A avaliacao da DTM foi realizada por meio do questionario Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC). Para a avaliacao da ansiedade foi aplicado o questionario Ansiedade Traco-Estado de Spielberger. Os resultados dos niveis de ansiedade e dos graus de DTM dos dois questionarios foram comparados pelo teste do qui-quadrado, com nivel de significancia de 5%. A analise estatistica mostrou que o grau de DTM tem relacao positiva para a Ansiedade-Estado (p = 0,008, p <0,05) e negativa para a ansiedade-traco (p = 0,619, p <0,05), alem disso, foi observado alto indice de DTM entre os estudantes (40%). Por meio dos resultados obtidos e analisados neste estudo, concluiuse que havia uma associacao positiva entre DTM e ansiedade.

Palavras chave: Desordem temporomandibular; Epidemiologia; Questionario; Prevalencia; Ansiedade e depressao.

INTRODUCTION

Temporomandibular disorder (TMD) is the most common noninfective pain condition of the orofacial region1. The term TMD has been described as a cluster of disorders characterized by pain in the preauricular area, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) or masticatory muscles; limitation or deviations in mandibular range of motion; and clicking in the TMJ during mandibular function, unrelated to growth or development disorders, systematic diseases, or macrotrauma2-6. A

pproximately 60-70% of the general population has at least one sign of such disorder at some stage in their life, however, only about 5% actually seeks treatment7. The most prevalent clinical signs of TMD are TMJ sounds (upon palpation), limitation of mandibular movements, TMJ and muscle tenderness4,8. With regard to subjective symptoms, headache, TMJ sounds, bruxism, difficulty in opening the mouth, jaw pain, and facial pain are found2. The etiology of TMD has both structural and psychological concepts. Structural concepts include conditions related to the TMJ itself (functional, structural, morphopathological, e.g., micro-/macrotrauma), conditions related to the muscles of mastication (muscle spasm, e.g., parafunctional habits) or occlusal factors (e.g., bruxism). Recent studies have shown that occlusal factors were not found to be directly involved with TMD; nevertheless they may contribute with other factors or aggravate an existing condition9. Psychological concepts include stressful life events, post-traumatic stress disorder, psychiatric illness (anxiety and depression)3,5,10-21, somatoform disorders, personality disorders (e.g., obsessive-compulsive disorder), hypochondriasis, paranoia, and schizophrenia15,17. In support of the above theory, a higher degree of psychological distress and altered personality traits have been observed in TMD patients9.

Over the years, several studies have called attention to the relationship between major life stressors and temporomandibular disorders (TMDs)22,23. The information regarding signs and symptoms of TMD has been collected by clinical examination and questionnaires in some studies or interview in others1,3,24,25. A number of authors around the world have found variables associated with TMD12,26,5, anxiety, and stress5,9,12-14,18,19,27-29. Moreover, anxiety in the school environment is a sufficiently interesting aspect of study, as it may influence student performance. It involves aspects related to identification of the sources that cause tension in students, what its effect on learning is, which students are most affected, and the forms of treatment; beyond which studies demonstrate that patients with TMD have high anxiety levels3,30. Clinicians may confuse the problem by concentrating on examination of the physical component (location and severity of pain, TMJ, and related muscles) and disregard the psychosocial and behavioral factors. The introduction of Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) for TMD by Dworkin and LeResche31 at the University of Washington, established a proper diagnostic criterion for this condition; this dual-axis system may be superior to other instruments since it can be used to classify and quantify both physical and psychosocial components of TMD15,20,32,33.

Research involving the psychological factors in TMD has serious deficiencies, not only derived from the diagnostic problems implicit in TMD, but also the lack of psychological instruments with a minimum guarantee of psychometric measurement34,35. To sum up, current research on psychological factors and TMD shows differences between the diagnostic groups in some psychological variables, such as distress and personality. On the other hand, the effect that the disorder has on the patient depends on some psychological factors, such as degrees of coping. Therefore, the aim of this paper was to seek differences in the anxiety levels associated with the group diagnosed with TMD, among Brazilian university students.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Volunteers

A total 150 volunteers participated in this study, with ages ranging from 17 to 30 years. The students were randomly selected from different courses in the field of human science at one public university and four private universities located in the cities of Bauru and Aracatuba, Sao Paulo, Brazil, respectively. All the volunteers were informed of the objectives of the study, and signed a formal consent of participation approved by the Research Ethics Committee.

Questionnaire

Assessment of anxiety: the self-evaluative questionnaire, Spielberger’s state-trait anxiety inventory36 was used to evaluate students’ state and trait anxiety. This inventory is made up of two questionnaires: trait-anxiety and state-anxiety. Each consists of 20 statements. The state-anxiety questionnaire assesses how the students feel at a particular times, and the trait-anxiety questionnaire assesses how they generally feel. Two subscales were scored separately with a maximum possible score of 80 for each. The results of the scores were compared to the questionnaire’s predetermined scores, determining the anxiety levels, as follows: (a) low anxiety (20 to 34 points); (b) moderate anxiety (35 to 49 points); (c) high or serious anxiety (50 to 64 points) and (d) Panic (65 to 80 points). The same volunteers were also asked some questions from the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC)31. The RDC/TMD is divided into 2 axes. Axis I involves the clinical TMD conditions, and axis II involves the pain-related disability and psychological status. As RDC/TMD is an internationally recognized and widely adopted tool for TMD research, its thirteen first questions from axis II were used in this study to classify the chronic pain of the students with TMD. According to the answers, chronic pain was classified into four different degrees: 0, 1, 2 and 3.

Data analysis

The results of the two questionnaires were compared between anxiety levels and severity degrees of chronic TMD pain by the chi-square test. The significance level was set at 5%.

RESULTS

The results obtained from Spielberger’s trait-anxiety inventory (36) showed that 39 students (26%) had low anxiety, 24 (48.70%) had moderate anxiety, 24 (16%) high or serious anxiety and 3 (2%) had panic anxiety (Fig 1).

Fig. 1: Frequency distribution (%) of the trait-anxiety inventory (n=150).

The results of the state-anxiety inventory showed that 43 students (28.7%) had low anxiety, 67 (44.7%) had moderate anxiety, 38 (25.3%) high or serious anxiety and 2 (1.3%) panic (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Frequency distribution (%) of the state-anxiety inventory (n=150).

According to RDC/TMD (24), the prevalence of TMD was 61 students (40.7%), while 89 students (59.3%) did not have TMD (Fig 3).

Fig. 3: Frequency distribution (%) according to presence or absence of TMD (n=150).

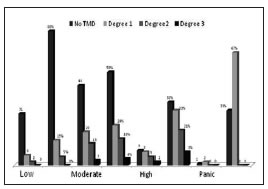

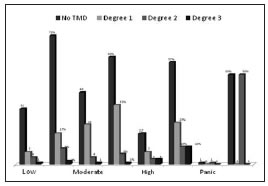

The correlation between trait-anxiety scores and chronic pain degrees was not significant and negative (p=0.619; p<0.05) (Fig 4). However, a significant correlation was revealed in relation to state-anxiety scores and chronic pain degrees (p=0.008; p<0.05) (Fig 5).

Fig. 4: Frequency distribution according to trait-anxiety scores and chronic pain degrees.

Fig. 5: Frequency distribution according to state-anxiety scores and chronic pain degrees.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to evaluate the relationship between signs of psychological distress and and temporomandibular disorder in Brazilian university students through the frequency distribution of the data obtained from a questionnaire. The etiology of TMD has been considered to be one of the most controversial issues in clinical dentistry. Currently, TMD is considered not a single entity, but a group of several varying diseases2. Figures 1 and 2 show that the greatest percentage of students had moderate anxiety according to both the trait-anxiety questionnaire (56%) and the stateanxiety questionnaire (44.7%).

Literature reports on academic stress and its repercussion on the health of university students3,37,38. Anxiety and depression are the most frequent clinical disorders in the general population, and are also significantly present among university students39,40. Their start, development and duration may be related to multiple factors, both situational and psychological. The importance of psychological factors in the etiology of TMD has often been emphasized, and they are believed to predispose the individual to chronicity3,11,15- 17,20,21. Weitzman et al.41, 2004, believe that the university is a critical context for studying the mental health of youth. According to Read et al.42, 2002, university students are often undergoing role transitions such as moving away from the family home for the first time, residing with other students, and experiencing reduced adult supervision. These changes may increase the risk of depression. In this study, 61 (40.7 %) of the university students had TMD. This value is slightly lower than that reported by Shiau and Chang43, 1992 (42.9%), Garcia et al.44, 1997 (61%), and Conti et al.45, 2003 (68%), all of whom used the same questionnaire to evaluate TMD in university students. Psychological factors provided some very interesting data in our study. Of the two anxiety questionnaires (Trait, State) tested, one (State) provided significant results in relation to TMD (Figures 3 and 4). These outcomes are in agreement with Bonjardim et al.11, 2005, Mazzetto et al.46, 2001, who asserted that anxiety plays an important role in TMD, acting as a predisposing or aggravating factor.

It is well accepted that psychological factors play a role in the etiology and maintenance of temporomandibular disorders (TMDs)5,9,10,12,14,18,27-29,47. In particular, a high incidence of exposure to stressful life events10 and elevated levels of anxiety and stress-related somatic symptoms have been reported in TMD patients. Findings regarding depression have been less consistent. Some investigators have reported elevated levels of depression9,12,13,19,48 whereas others have found no differences between TMD patients and normal controls49.

TMD is often associated with somatic and psychological complaints, including fatigue, sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression11,20. Thus, considering that stress is associated with psychological disturbances such as anxiety and depression50, we can say that there appears to be a relationship between stress and degree of TMD in our study. It is difficult to measure a variable as subjective as anxiety, and although an effort has been made to validate the questionnaires, variables such as sex, age, race, climate, time, and social condition all arise as factors that may or may not influence anxiety5.

CONCLUSIONS

According to the results, it was concluded that there is a positive, statistically significant association between DTM and anxiety.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The autors wish to thank Maria Lucia Marcal Mazza Sundefeld for the statistical analysis.

1. Farsi NMA (2003) Symptoms and signs of temporomadibular disorders and oral parafunctions among Saudi children. J Oral Rehabil 30:1200-1208. [ Links ]

2. Bonjardim LR, Gaviao MBD, Pereira LJ, Castelo PM, Garcia RCMR. Signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders in adolescents. Braz Oral Res 2005;19:93-98. [ Links ]

3. Bonjardim LR, Lopes-Filho RJ, Amado G, Albuquerque RL Jr, Goncalves SR. Association between symptoms of temporomandibular disorders and gender, morphological occlusion, and psychological factors in a group of university students. Indian J Dent Res. 2009;20:190-194. [ Links ]

4. Carvalho CM, de Lacerda JA, Dos Santos Neto FP, Cangussu MC, Marques AM, Pinheiro AL. Wavelength effect in temporomandibular joint pain: a clinical experience. Lasers Med Sci. 2010;25:229-232 [ Links ]

5. Casanova-Rosado JF, Medina-Solis CE, Vallejos-Sanchez AA, Casanova-Rosado AJ, Hernandez-Prado B, Avila-Burgos L. Prevalence and associated factors for temporomandibular disorders in a group of Mexican adolescents and youth adults. Clin Oral Investig. 2006 Mar;10:42-49. [ Links ]

6. Thilander B, Rubio G, Pena L, de Mayorga C. Prevalence of temporomandibular dysfunction and its association with malocclusion in children and adolescents: na epidemiologic study related to specified stages of dental development. Angle Orthod 2002;72:146-154. [ Links ]

7. Macfarlane TV, Gray RJM, Kincey J, Worthington HV. Factors associated with the temporomandibular disorder, pain dysfunction syndrome (PDS): Manchester case control study. Oral Diseases 2001;7,321-330. [ Links ]

8. Sonmez H, Sari S, Oksak Oray G, Camdeviren H. Prevalence of temporomandibular dysfunction in Turkish children with mixed and permanent dentition. J Oral Rehabil 2001;28:280-285. [ Links ]

9. Pallegama RW, Ranasinghe AW, Weerasinghe VS, Sitheeque MAM. Anxiety and personality traits in patients with muscle related temporomandibular disorders. J Oral Rehabil 2005;32:701-707. [ Links ]

10. Alamoudi N. Correlation between oral parafunction and temporomandibular disorders and emotional status among Saudi children. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2001;26:71-80. [ Links ]

11. Bonjardim LR, Gaviao MB, Pereira LJ, Castelo PM. Anxiety and depression in adolescents and their relationship with signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders. Int J Prosthodont 2005;18:347-352. [ Links ]

12. Carlson CR, Reid KI, Curran SL, Studts J, Okeson JP, Falace D et al Psychological and physiological parameters of masticatory muscle pain. Pain 1998;76:297-307. [ Links ]

13. Glaros AG, Karen W, Leonard L. The role of parafunctions, emotions and stress in predicting facial pain. J Am Dent Assoc 2005;136:451-458. [ Links ]

14. Grossi ML, Goldberg MB, Locker D, Tenenbaum HC. Reduced neuropsychologic measures as predictors of treatment outcome in patients with temporomandibular disorders. J Orofac Pain. 2001;15:329-339. [ Links ]

15. Jerjes W, Madland G, Feinmann C, Hopper C, Kumar M, Upile T, Kudari M, Newman S. A psychological comparison of temporomandibular disorder and chronic daily headache: are there targets for therapeutic interventions?. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007;103:367-373. [ Links ]

16. Kino K, Sugisaki M, Ishikawa T, Shibuya T, Amagasa T, Miyaoka H. Preliminary psychologic survey of orofacial outpatients: Part 1, Predictors of anxiety or depression. J Orofac Pain 2001;15:235-244. [ Links ]

17. Oliveira AS, Dias EM, Contato RG, Berzin F. Prevalence study of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorder in Brazilian college students. Braz Oral Res 2006;20:3-7. [ Links ]

18. Phillips JM, Gatchel RJ, Wesley AL, Ellis E. III Clinical implications of sex in acute temporomandibular disorders. J Am Dent Assoc 2001;132:49-57. [ Links ]

19. Velly AM, Philippe P, Gornitsky M. Heterogeneity of temporomandibular disorders: cluster and case–control analyses. J Oral Rehabil 2002;29:969-979.

20. Yap AU, Dworkin SF, Chau EK, List T, Tan BC, Tan HH. Prevalence of temporomandibular disorder subtypes, psychologic distress, and psychosocial dysfunction in Asian patients. J Orofac Pain. 2003;17:21-28. [ Links ]

21. Yap AU, Tan KB, Hoe JK, Yap RH, Jaffar J. On-line computerized diagnosis of pain-related disability and psychological status of TMD patients:A pilot study. J Oral Rehabil 2001;28:78-87. [ Links ]

22. De Leeuw R, Bertoli E, Schmidt JE, Carlson CR. Prevalence of Traumatic Stressors in Patients With Temporomandibular Disorders. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005;63: 42-50. [ Links ]

23. Korszun A. Facial pain, depression and stress - Connections and directions. J Oral Pathol Med 2002;31:615-619. [ Links ]

24. Gavish A, Halachmi M, Winocur E, Gazit E. Oral habits and their association with signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders in adolescent girls. J Oral Rehabil 2000;27:22-32. [ Links ]

25. Sari S, Sonmez H. Investigation of the relationship between oral parafunctions and temporomandibular joint dysfunction in Turkish children with mixed and permanent dentition. J Oral Rehabil 2002;29:108-112. [ Links ]

26. Plesh O, Sinisi SE, Crawford PB, Gansky SA Diagnoses based on the Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders in a biracial population of young women. J Orofac Pain 2005;19:65-75. [ Links ]

27. Tsai CM, Chou SL, Gale EN, McCall WD Jr. Human masticatory muscle activity and jaw position under experimental stress. J Oral Rehabil 2002;29:44-51. [ Links ]

28. Uhac I, Kovac Z, Valentic-Peruzovic M, Juretic M, Moro LJ, Grzic R. The influence of war stress on the prevalence of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders. J Oral Rehabil 2003;30:211-217. [ Links ]

29. Velly AM, Gornitsky M, Philippe P. Contributing factors to chronic myofascial pain: a case-control study. Pain 2003; 104:491-499. [ Links ]

30. Marchiori AV, Garcia AR, Zuim PRJ, Fernandes AUR, Cunha LDP. Relacao entre a disfuncao tempomandibular e a ansiedade em estudantes do ensino fundamental. Pesq Bras Odontoped Clin Integr 2007;7:37-42. [ Links ]

31. Dworkin SF, LeResche L. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: review, criteria, examinations and specifications, critique. J Craniomandib Disord 1992;6:301-355. [ Links ]

32. Ahmad M, Hollender L, Anderson Q, Kartha K, Ohrbach R, Truelove EL, John MT, Schiffman EL. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (RDC/TMD): development of image analysis criteria and examiner reliability for image analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2009;107:844-860. [ Links ]

33. Lee LTK, Yeung RWK, Wong MCM, Mcmillan AS. Diagnostic sub-types, psychological distress and psychosocial dysfunction in southern Chinese people with temporomandibular disorders. J Oral Rehabil 2008;35:184-190. [ Links ]

34. Callahan CD. Stress, coping and personality hardiness in patients with temporomandibular disorders. Rehabil Psychol 2000;45:38-48. [ Links ]

35. Ferrando M, Andreu Y, Galdo MJ, Dura E, Poveda R, Baga JV. Psychological variables and temporomandibular disorders: Distress, coping, and personality. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2004;98:153-60. [ Links ]

36. Manual for the statetrait anxiety inventory. Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. 1970. Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc. [ Links ]

37. Pellicer O, Salvador A, y Benet I.A., Efectos de un estresor academico sobre las respuestas psicologica e inmune en jovenes. Psicothema. 2002;14:317-322. [ Links ]

38. Martin IM. Estres academico en estudiantes universitarios. Apuntes Psicol 2007;25:87-99. [ Links ]

39. Perales A., Sogi C. y Morales R., Estudio comparativo de salud mental en estudiantes de medicina de dos universidades estatales peruanas. An Fac Med Univ Nac Mayor San Marcos. 2003;64:239-246.

40. Riveros M, Hernandez H. y Rivera J. Niveles de depresion y ansiedad en estudiantes universitarios de Lima Metropolitana. Rev Inv Psicol. 2007;10:92-102.

41. Weitzman E.R. Poor mental health, depression, and associations with alcohol consumption, harm, and abuse in a national sample of young adults in college. J Nerv Ment Dis 2004;192:269-277. [ Links ]

42. Read J.P., Wood M.D., Davidoff O.J., McLacken J., Campbell J.F. Making the transition from high school to college: the role of alcohol-related social influence factors in students’ drinking. Subst Abuse 2002;23:53-65.

43. Shiau Y, Chang C. An epidemiological study of temporomandibular disorders in university students of Taiwan. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1992;20:43-47. [ Links ]

44. Garcia AL, Lacerda NJ, Pereira SLS. Grau de Disfuncao da ATM e dos movimentos mandibulares em adultos jovens. Rev APCD 1997;51:46-51. [ Links ]

45. Conti A, Freitas M, Conti P, Henriques J, Janson G. Relationship between signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders and orthodontic treatment: A cross-sectional study. Angle Orthod 2003;73:411-417. [ Links ]

46. Mazzetto MO. Alteracoes psicossociais em sujeitos com desordens cranio craniomandibulares. J Bras Oclusao, ATM & Dor Orofacial 2001;1:223-243. [ Links ]

47. Lindroth JE, Schmidt JE, Carlson CR. A comparison between masticatory muscle pain patients and intracapsular pain patients on behavioral and psychosocial domains. J Orofac Pain. 2002;16:277-283. [ Links ]

48. Auerbach SM, Laskin DM, Frantsve LME, Orr T. Depression, Pain, Exposure to Stressful Life Events, and Long-Term Outcomes in Temporomandibular Disorder Patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2001;59:628-633. [ Links ]

49. Marbach JJ. The ’temporomandibular pain dysfunction syndrome’ personality: fact or fiction? J Oral Rehabil. 1992;19:545-560.

50. Gameiro GH, da Silva Andrade A, Nouer DF, Ferraz de Arruda Veiga MC. How may stressful experiences caontribute to the development of temporomandibular disorders? Clin Oral Investig 2006;10:261-268. [ Links ]