Introduction: fighting or breeding?

Can mayors affect the electoral performance of their party beyond the municipal level? What effect does intra-party conflict have on the perfor mance of a party? A famous quote from Juan Domingo Peron, founder of the Peronist Party, states that Peronist are like cats because while everyone thinks they are fighting, they are actually breeding. If that phrase is still true, conflict inside the Peronist Party should not hurt its electoral performance. However, is that so?

Articulo aceptado para su publicación el 26 de abril de 2019.

Revista SAAP (ISSN 1666-7883) Vol. 13, N° 1, mayo 2019, 137-156

Identifying the effect of intra-party conflict on political performance is hard as many other variables that influence electoral performance might very well co-vary with intra-party conflict. In other words, territorial units and/or elections in which there is intra-party conflict are likely to be very different from those in which there is none. However, a peculiar phenom- enon of administrative boundaries in the province of Buenos Aires provides an opportunity for isolating the effect of intra-party competition. Some lo cal entities (i.e., cities and towns) are located on the limit between two differ ent municipalities, thus belonging to two distinct administrative units, but remaining a single unit for most other purposes. This implies that most of the variables affecting electoral behavior are likely to be constant across the whole administrative unit except for those associated with the municipality to which each part of the unit belongs. We take advantage of this phenom- enon and use electoral data at the polling station level from the 2015 guber- natorial and presidential elections for three of those split localities to analyze if voters behaved differently in municipalities where intra-party conflict in the Peronist Party was more salient. If Peronists are fighting, then we should expect ballot splitting, which would hurt the performance of the Peronist Party, in those municipalities in which the mayor is not aligned with his party’s gubernatorial candidate. However, if Peron’s maxim applies to this election and they are indeed breeding, intra-party conflict should not affect the party’s electoral performance. Our results suggest that a both substan- tively and statistically significant negative effect of intra-party conflict on electoral performance in two of the three split localities.

This research notes proceeds as follows: Section lays out the case and motivation. In particular, it justifies the focus on the 2015 province of Buenos Aires’ election and the selection of administrative units for the empirical analysis. Section 3 then presents the data and methodology we use, and Section 4 reports the results of the empirical analysis. Finally, Section 5 concludes.

Case and Motivation

Divided parties

The province of Buenos Aires is the biggest Argentinean province in both demographic and economic terms, encompassing almost 40% of the Argentinean population and around 34% of the nation’s GDP It is divided into 135 political divisions called «partidos», which are functionally equiva- lent to what is called «municipality» in other provinces and countries. Most of these administrative units have been governed by the Peronist Party since the return of democracy in 1983, which has also held the province’s gover- norship for most of the period. However, the Peronist party lost control of the province and many of its administrative units in the 2015 elections.

The defeat of the Peronist Party came as a surprise for many of the province’s residents, as well as for politicians and political scientists who have since been trying to explain what happened. Apart from accounts based on the characteristics of the new governor, María Eugenia Vidal (also the first woman to ever hold that office), many explanations have focused on the internal conflicts inside the Peronist Party. This explanation, in turn, is tied to two factors: the electoral reform of 2009, and the party paper ballots which Argentineans use to cast their votes. The electoral reform is relevant because it introduced primaries that provide a straightforward way to iden- tify internal party splits, all while keeping the electorate unchanged. The fact that the Peronist gubernatorial primary in 2015 was won by a controver- sial candidate who lacked the support of some sections of the electorate, moreover, meant that some Peronist mayors had strong incentives to dis- tance and dissociate themselves from their party’s gubernatorial candidate. On the other hand, the peculiarities of Argentina’s party paper ballots are important, as they make vote splitting particularly hard.

In 2009, a reform was passed in the Argentinean Congress that modi- fied many regulations regarding political parties, electoral campaigns, and elections (the reform was, in fact, called «Reforma Política», political reform). What is relevant here is that the reform introduced compulsory primaries («primarias abiertas simultáneas y obligatorias» (PASO)). These primaries are held simultaneously and are compulsory for both citizens and parties. Citizens are required to participate in them, but they can only pick a single list or candidate (i.e., they cannot vote in more than one primary for the same category). Meanwhile, parties and coalitions have to hold primary elec tions, even if they only field a single candidate, and need to obtain a mini- mum of 1.5% of the valid votes to participate in the following general elec- tions. Since the primaries were introduced, the Peronist Party has tended to arrive at the primaries with only one single candidate for each executive position, de facto allowing primary voting only for legislative positions. In the 2015 Buenos Aires gubernatorial elections, however, the party was un- able to achieve internal unity. After the person chosen by Argentina’s Presi- dent (and informal head of the Peronist Party) declined to run for the governor’s office, the Peronist Party could not reach an agreement on one single candidate. This disagreement was mainly caused by the controversial

nature of the candidate who was also the President’s Chief of Cabinet at the time, Anibal Fernández. Not only is he well known for his blunt statements and original quotes (he even caught the attention of the international press for quoting Jon Bon Jovi and Los Redondos while defending the government’s budget bill),4 but he has also been accused of involvement in drug traffick- ing.5 He was thus a candidate many mayors found difficult to endorse. Consequently, Fernández did not win unanimous party support for his can- didacy and had to compete in the primaries with Julián Domínguez, a former mayor, legislator, and minister.

For elections in most Argentinean provinces, ballots are issued per party and cover all the offices, both legislative and executive, for which the party is fielding candidates.6 If citizens want to vote for the same party for all offices, they can simply insert the party ballot of their choice into an envelope and cast it. If citizens want to vote for different parties for different offices, how- ever, they need to physically cut the paper ballots and insert only that part of the party ballot into the envelope which contains the candidate and office they wish to vote for. The process of cutting the ballot is time-consuming and cutting the ballot the wrong way can easily spoil it, nullifying the vote. There- fore, most voters prefer to vote for the complete list or, in case they decide to «cut the ballot», only one of the two ends of the ballot, i.e. the candidate for president or for mayor. As a consequence, having an intra-party conflict at the governor level, i.e., in a category right in the middle of the ballot, can be detrimental to the party’s electoral performance. Many opponents of the party’s candidate for the governorship will prefer to vote for another party altogether, or do one single cut, thus, either voting only for the party’s candidate for the presidency or for the mayor’s office. There has indeed been evidence of in- creased rates of «ballot cutting» in recent years and in this particular elec- tion,7 resulting in different parties winning different offices in 59 of the province’s 135 «partidos» (see Appendix 2), as well as important differences in votes between mayoral and gubernatorial candidates at the municipal level (Appendix 3). Most of the evidence, however, is still non-conclusive.

Divided cities and the railway

The 135 municipalities, or «partidos», that constitute the province of Buenos Aires were established by provincial law and are not tied to mini- mum population requisites. Out of the 552 entities which exist inside these «partidos» , we have identified three units which both belong to two differ- ent partidos and were subject to intra-party conflict around the Peronist’s gubernatorial candidate: San Francisco Solano, El Palomar, and Mechita. To our knowledge, these three cases are the only administrative units of the province of Buenos Aires that belong to two different «partidos» and in which one mayor supported Fernández while the other supported Domínguez for the 2015 gubernatorial Peronist primary election.

The three cases represent different regions of the province of Buenos Aires. San Francisco Solano and El Palomar are two urban areas located in the metropolitan area of the city of Buenos Aires. The former lies within the so-called «Primer Cordón» (first conurbation), formed by those localities that lie closest and are best connected to the national capital, while the latter is part of the «Segundo Cordón» (second conurbation) and is located half way between Buenos Aires and the provincial capital La Plata. The popula- tion of both El Palomar and the slightly bigger San Francisco Solano are considered urban. This contrasts with the smaller Mechita, a town with a mixed urban-rural population about 130 miles from the city of Buenos Aires.

Each of these three entities belongs to two different municipalities, or «partidos», and is thus governed by two distinct administrations. The mu nicipalities of both El Palomar and Solano are similar on a number of im- portant characteristics (see Appendix 4). By contrast, Mechita belongs to two municipalities that, even though they share many characteristics, have different population densities. In all cases, though, the main economic in- dicators, as well as the level of fiscal independence from other levels of gov- ernment, are more similar between the two municipalities in which each entity lies than between entities. Furthermore, the municipalities of all three entities were governed, in 2015, by members of the same political coalition inside the Peronist Party, namely the «Frente para la Victoria» (FpV). More- over, their mayors supported different candidates during the primaries. In each of the three entities we identified, one of the mayors supported the winning (and controversial) candidate, Anibal Fernández, while the other supported the loosing candidate, Julián Domínguez, in conflict with the official party nomination. Moreover, many of the mayors who supported Domínguez during the primaries did it based on their profound opposition

to Fernández, henee, making it hard (or in some cases virtually impossible) to later eampaign in favor of the official eandidate for governor.

Another reason for ehoosing these cases is that their histories are tightly linked to the development of Argentina’s railway and the boundaries can, thus, be considered «as-if» random. Mechita was founded in 1904 as a con- sequence of the construction of a railway workshop for the Sarmiento line of Buenos Aires Western Railway (Ferrocarril Oeste de Buenos Aires). Its location was a result of the combination of the need of a foreign railway company and a legal dispute. When the owners of the land where the com- pany initially intended to locate the workshop refused to sell, then-presi- dent Manuel Quintana donated some of his personal landholdings located nearby. El Palomar, similarly, was established with the train station of the same name belonging to the Buenos Aires and Pacific Railway (Ferrocarril Buenos Aires al Pacífico) inaugurated in 1910. After the train station started operating, the surrounding lands, barely populated at the time, were di- vided into small lots and sold with the purpose of constructing family homes. In the last case of the town of San Francisco Solano, its territory had be- longed to the Franciscan Order until they were sold first in 1721 to Juan Rubio, and later in 1826 to Manuel Obligado, in whose family they remained for over a century. The train arrived in 1927 with a station from the train line that connected the city of Buenos Aires with the provincial capital of La Plata. The town itself, however, was only established in 1948 when a real estate company bought the lands from the Obligado family in order to sell small plots to individuals. Shortly thereafter, the authorities of the province formally authorized the establishment of the town in May of 1949.

Data and Methodology

3.1. Data

To investigate whether intra-party conflict affects party performance in elections, we have gathered electoral data from the three selected towns in the province of Buenos Aires. In total, we have data for both the 2015 presi- dential and gubernatorial election from 314 different precincts in 41 differ- ent polling stations across the three towns (see Table 1). Each town belongs to two different municipalities which where both run by the Peronist Party prior to the 2015 election. For each case, however, one municipality sup- ported the official gubernatorial candidate of the Peronist Party, Anibal

Fernández while the other did not. We can therefore difFerentiate between polling data from municipalities in which there was no intra-party conflict because the mayor supported the party’s official candidate for governor (control), and municipalities in which the mayor did not support the official candidate and thus caused intraparty conflict (treatment). A simple differ- ence-in-means test indicates that there is indeed a difference in the percent- age of votes obtained by the Peronist Party in the treatment and control municipalities in all three towns (see Table 2). This difference is negative and statistically significant for both the presidential and gubernatorial elec- tions in Mechita and El Palomar. However, the difference in votes in San Francisco Solano does not reach significance. The magnitude of the effect seems to be similar for presidential and gubernatorial elections in all three municipalities, as can be seen in column three of Table 2, and is substan- tively significant in both Mechita, where it is around 17 percentage points, and El Palomar, where it is around 10 percentage points.

Table 1

Polling Stations and Precincts

Entity

Polling Station

Precincts

TCTCMechita

1132El Palomar

516

41

126

San Feo. Solano

15

3119

23

Table 2

Differences in means and T-Scores

Entity

Presidential election

Gubernatorial election

Difference

Difference

T-score

Difference

T-score

Difference

T-score

Mechita

-0.165

-5.59

-0.17

-7.51

0.005

0.13

El Palomar

-0.109

-19.01

-0.1

-18.53

-0.01

-1.23

San Feo. Solano

0.011

0.94

0.004

0.37

0.007

0.47

Methodological Strategy

To analyze our data more thoroughly, we first employ a geographic re- gression discontinuity design. In particular, we are interested in the share of votes in the presidential and gubernatorial election for the Peronist list of Frente para la Victoria, our dependent variable, and how it is affected by intra-party conflict, our independent variable. As explained in the previous section, we argue that the municipal borders are set exogenously, meaning that treatment, i.e., residing in a municipality that experiences intra-party conflict, is assigned randomly.

Unfortunately, we were unable to gather fine-grained data to assess the similarity of the populations around the boundaries, which is why we rely on our qualitative research on the establishment of the borders and general socioeconomic and political indicators at the municipal level that can be seen in Appendix 4. We can then interpret the distance of each polling station to the municipal border as a forcing variable which perfectly deter mines treatment status. In praxis, this means that we geolocated each poll ing station and manually measured its distance to the municipal border (see Appendix 6 for maps).

However, we are cautious to interpret our results as causal. First, viola- tions of the single unit treatment value assumption (SUTVA) are not im plausible since treatment spillovers are likely to happen in densely popu- lated urban areas. Second, we need to assume the continuity of our condi- tional expectation fonctions. In geographic discontinuity designs, however, this is «more likely to be violated, since agents are better able to sort around the discontinuity» (Keele & Titiunik, 2015, p. 127). Nevertheless, since the pair of municipalities to which each of the entities belongs share many simi- larities, it is possible to hypothesize that the incentives for voters to sort around the geographic boundary are rather small.

Taking these potential violations of the necessary assumptions for a causal interpretation into account, we proceed with the computation of the regression discontinuity using a simple linear model:

E[Yi | Xi, Di]=a+xDi+pXi

where Yi is the dependent variable, that is the vote share of Frente para la Victoria in the 2015 presidential and gubernatorial elections, D i is a binary variable indi- cating treatment, i.e., being located in a municipality that experiences intra- party conflict, X is the forcing variable, i.e., the distance of the polling station to the border of the control municipality measured in miles (it is negative for control units), and t is the estimand, that is the average treatment effect.

Results

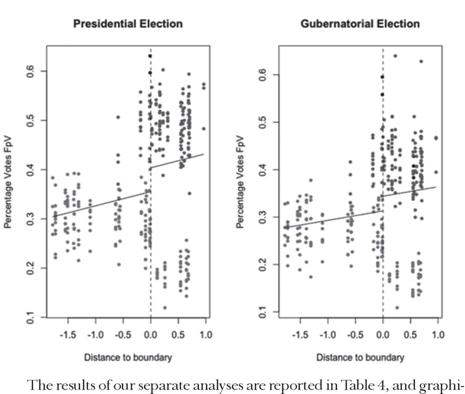

Our estimation results are reported in the first two columns of Table 3, and graphically displayed in Figure 1. Being located in a municipality that experiences intra-party conflict seems to increase the party’s electoral per formance by almost five percentage points in the presidential election, and around three percentage points in the gubernatorial election. These are sub- stantively important results, as the Peronist party lost the 2015 gubernato rial election in Buenos Aires by only 4.14 percentage points, and the presi dential election nationwide by only 2.68 percentage points. However, these results might be misleading since we are looking at all three towns con- jointly. We only expect the area just across the border in the treatment mu nicipality of town A to be similar to the area close to the border in the control municipality of town A, but not in town B or C. We can indeed see in Figure 2 that the data are indeed very much clustered by unit. More evidence in line with this intuition is provided in Columns 3 and 4 of Table 3, where we

Figure 1

included fixed effects for San Francisco Solano and Mechita, leaving El Palomar as the residual category. We therefore decide to run the regression discontinuity separately for both San Francisco Solano and El Palomar, leav ing aside Mechita which has only 2 polling stations and 5 precincts (see Table 4).

Figure 2

RD, All precincts, color by entity

cally displayed in Figures 3 and 4. The results for our analysis for both the presidential and gubernatorial election of San Francisco Solano (Figure 4 and columns 3 and 4 in Table 4) indicate a slightly positive but potentially insignificant treatment effect. The data from El Palomar, however, predict a substantially and statistically significant negative treatment effect, as illus- trated in Figure 3 and reported in the first two columns of Table 3. A nega- tive effect of 4 percentage points is important given that both elections were lost by the Peronist party by smaller margins.

Table 3

RDD, Linear models

Total

With dummies

di

(2)

(1)

(2)

Treatment

0.048***

0.031*

-0.045***

-0.042***

(0.021)

(0.018)

(0.009)

(0.009)

Distance

0.029**

0.020*

-0.02***

-0.02***

(0.013)

(0.011)

(0.006)

(0.006)

San Feo Solano

0 26***

0.206***

(0.007)

(0.007)

Mechita

0.273***

0.258***

(0.022)

(0.023)

Constant

0.355***

0.313***

0.275***

0.248***

(0.014)

(0.012)

(0.006)

(0.006)

N314

314

314

314

R 2

0.129

0.084

0.842

0.76

Adjusted R 2

0.123

0.078

0.84

0.757

*n< .1: **o < .05: ***t> < .01

Note: (1) Presidential Election; (2) Gubernatorial Election

Table 4

RDD, Linear models by local entity

El Palomar

San Feo Solano

(1)

(2)

(1)

(2)

Treatment

-0.1***

-0.09***

0.011

0.012

(0.01)

(0.01)

(0.015)

(0.016)

Distance

-0.007

-0.007

0.0002

-0.014

(0.006)

(0.005)

(0.016)

(0.018)

Constant

0.295***

0.226***

0.482***

0.407***

(0.006)

(0.006)

(0.01)

(0.012)

N167

167

142

142

R 2

0.584

0.559

0.007

0.005

Adjusted R 2

0.579

0.554

-0.007

-0.009

*d< .1: **o < .05: ***d < .01

Note: (1) Presidential Election; (2) Gubernatorial Election

We also use a different approach to corrobórate our results. Specifically, we include the geographical coordinates, meaning the latitudinal and lon gitudinal location, of each polling station in our dataset. We then match each treated polling station with an untreated control unit, based on the unit’s latitudinal and longitudinal coordinates as well as the interaction of the two and the municipality in which they are located. We then estimate the treatment effect with a simple difference-in-means test using just our matched data, the results of which are presented in Table 5. We find a sig- nificant and negative treatment effect of approximately three percentage points for both the presidential and gubernatorial election, meaning effects that are larger than the margin of victory in those elections.

Table 5

Matching on Geographic Coordinates

Presidential Election

Gubernatorial Election

Treatment

-0.031**

-0.032***

Standard Error

0.012

0.012

N314

314

*p< .1; **p < .OS; ***p < .01

As a final estimation strategy, we subset our data to polling stations that are very close to the municipal borders passing through the three towns (we highlighted these polling stations on the maps in Appendix 6). We first estimate the differences in means (see Table 6) and find a negative differ- ence for both elections. We then run the same linear regression discontinu- ity model as before on the subset data, first for all of the precincts, then separated by town (see Table 7). We again see a substantively and statistically negative treatment effect of approximately ten percentage points for both the presidential and gubernatorial election in El Palomar, and this time a significant positive treatment effect in the city of San Francisco Solano. Moreover, the overall effect is in this case negative as the number of units included in the analysis in similar for both El Palomar and San Francisco Solano.

Table 6

Differences in means and T-Scores, subset

Presidential Election

Gubernatorial Election

Difference

Difference

-0.047

-0.046

-0.001

T-score

-1.821

-2.165

-0.03

Table 7

RDD, Linear models, subset

Total

El Palomar

San Feo Solano

(o

(2)

(o

(2)

(i)

(2)

Treatment

-0.047*

-0.046**

-0.102***

-0.091***

0.025*

0.015

-0.025

-0.021

-0.009

-0.009

-0.014

(0.013)

Constant

0.372***

0.327***

0.293***

0.264***

0.482***

0.410***

-0.017

-0.014

-0.006

-0.006

-0.01

(0.009)

N118

118

69

69

44

44

R 2

0.029

0.04

0.643

0.598

0.07

0.030

Adjusted R 2

0.021

0.032

0.638

0.592

0.048

0.007

*p< .1; **p < .OS; ***p < .01

Note: (1) Presidential Election; (2) Gubematorial Election

Final Comments

In this paper, we took advantage of the fact that some localities in the province of Buenos Aires belong to two different administrative units, i.e., municipalities, to assess the effect of intra-party conflict on party perfor mance. Our results suggest that the Peronist Frente para la Victoria per- formed differently within the same locality depending on the administra tive unit. We claim that this effect is a consequence of intra-party conflict affecting the party performance at different levels. However, the effect ap- pears to be quite heterogenous. In both Mechita and El Palomar, our results suggest a both substantively and statistically significant negative effect of intra-party conflict on electoral performance. In San Francisco Solano, on the other hand, we find a much smaller and only weakly significant positive treatment effect. Further qualitative research into the dynamics of intra- party conflict in those municipalities could help explain this heterogenous effect.

Municipios

55 Municipios: Adolfo Alsina, Arrecifes, Ayacucfio, Bahía Blanca, Balcarce.Qtragadq, Brandsen, Campana, Carlos Tejedor, Chacabuco, Coronel Dorrego, Coronel RosalesTCoroñel Suarez, Dolores, Florentino Amegtiino, General Arenales, General Belgrano, General Guido, General Lamadríd, General Lavalle, General Madanaga, General Pueyrredón General Viamonte, General Villegas.JuQÍn, La Plata, ,las Flores, lezama, Lincoln, Lobería, Lobos, Lujan, Magdalena, MaipúMorór^tueve de julio, Olavarria, Petlegrinl, Pergamino, Pínamar, Puan, Rauch, Rivadavia, Rajas, saladillo, Sallwueto San Cayetano. San Isidro, San Pedro,

Suipacha, Tandil. Tomauist. Trenque Lauquenjflres de Febreifr Vicente López

19 Municipiosftlbertj^ázul, Bolívar, Capitán SarmTento, Carlos Casares, Castelli, Daireux, Exaltación de laCnSTueneral Alvear, General Paz, Guaminí, Hipólito Yngoyen, La Costa, Mercedes, Roque Pérez, Saevedra, Salto. San Antonio de Areco, Veinticinco de Mayo

S Municipios: Chascomús, General Alvarado, Monte. Necochea, San Andrés de Giles 3 Municipios: Coronel Pringles, Tres Arroyos, Villarino

9jjujQÍdpios: Baradero. Benso, General Rodríguez, Lanus. Mar Chiquita, Patagones, Pilar. ^uilme^San Vicente

15 Municipios Avellaneda. Colón, Escobar, General Pinto, General San Martin, Ituzaingo Juárez. Laprida. Leandro N Alem, Navarro, Pehuajó. Ramailo. San Nicolás, Tapalque, Villa Gesell

1 Municipio: Zarate

20 Municipios:Odmirante Browr& Berazategui. Cañuelas, Esteban Echeverría, Ezeiza, Florencio Vareta, González cnaveT Hurlingham, José C Paz. Lomas de Zamora, Malvinas Argentina, Marcos Paz, Matanza, Merlo, Monte Hermoso, Moreno, Pila, Presidente Perón, Tordillo, Tres Lomas

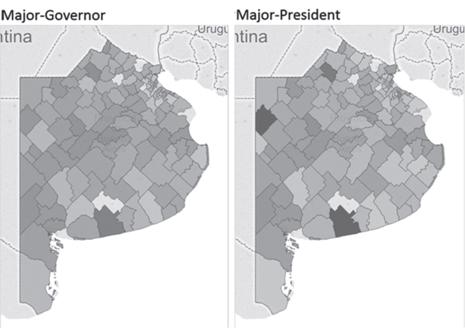

6.3. Appendix 3: Differences in votes between the candidate for mayor and the candidates for governor and president at the municipal level

Light grey indicates a better performance of the mayor, while darker grey indicates a worse performance of the mayor.

Source: Moscovich, Lorena and Antennuci, Pedro. «La conexión local, Bastión Digi tal, November 2015. Available at http://ar.bastiondigital.com/notas/la-conexion-local.

6.4. Appendix 4

El Palomar

Mechita

San Francisco Solano

3 de Febrero

Moron

Alberti

Bragado

Alm. Brown

Quilines

Year established

1959

1785

1910

1851

1873

1784

Mayor’s Party at t

PJ-FpV

NV-FpV

PI-FpV

PT-FpV

PJ-FpV

MS-FpV

Mayor's Party att+1

Cambiemos

Cambiemos

PJ-FpV

Cambiemos

PJ-FpV

Cambiemos

Population

343710

321109

10654

41336

552902

582943

Urban/Rural

Urban

Urban

Mixed

Mixed

Urban

Urban

HDI

0.884

0.886

0.899

0.879

0.835

0.87

% UBN*

4.3

3.5

2.2

3.7

10.4

9.2

Unemployment

5.51

5.98

2.87

4.32

7.07

6.79

Own Resources

0.45

0.52

0.28

0.25

0.37

0.45

Mayor's candidate

Domínguez

Fernández

Fernández

Domínguez

Fernández

Domínguez

*Uníulfilled Basic Needs

PT: Partido Tusticialista: FdV: Frente Dara la Victoria: NV: Nuevo Encuentro: PolS: Pblo So cial: PRO: ProDuesta Remiblicana

Own elaboration based on data from the 2010 National Census. United Nations Develomnent Proeram. Municroal websites, and the National Electoral Office

Socieconomic and Political Indicators, analyzed Municipalities

6.5. Appendix 5:

El Palomar

Mechita

San Francisco Solano

3 de Febrero

Moron

Alberti

Bragado

Alm. Brown

Quilines

President

19%

30%

61%

45%

48%

49%

Gobemor

17%

28%

58%

41%

41%

41%

Mean Frente para la Victoria percentage of votes in each municipality/unit

6.6. Appendix 6: Maps

El Palomar

Mechita

San Francisco Solano