This paper reports on one of the first practical applications of the Transition Design process that is currently taking place in Ojai, California. Transition Design is being developed at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) as a practice to address complex issues such as climate change, forced migration, poverty, crime, etc. The recent California drought, which affected the city of Ojai incommensurately, and polarized community sentiments in response, made this area an ideal case study for Transition Design in practice.

The Ojai project began with two workshops that engaged a diverse group of stakeholders from the community in a Transition Design process facilitated by Terry Irwin and Gideon Kossoff in January 2017 and Irwin, Kossoff, and the author in May 2017. By exploring a long-term solution process for the catastrophic drought conditions the valley has been suffering from for many years, and which remain unabated despite a winter that brought record rains and snowfall throughout the state, the workshops not only revealed areas of conflict between a diverse group of stakeholders but also fostered a new sense of optimistic hope for a collectively generated long-term solution to Ojai’s chronic water woes.

The content of the workshops was well documented in two papers uploaded to academia. com in January and May 2017 (Irwin & Kossoff, 2017; Irwin, Kossoff, & Hamilton, 2017). This paper explores the dynamics achieved during the workshops and how they catalyzed the community’s perspectives on water by viewing the crisis through the lens of a Transition Design process.

Ojai, California and the Need for Transition

Several factors make the water shortage in Ojai an ideal case study for the Transition Design process. These features include an open-minded population with a history of countercultural and progressive thinking, an active crisis (severe water shortage), a geographically isolated location that amplifies the need for local action, and a manageable scale that makes the goal of engaging virtually all citizens of the valley in the process of developing long-range solutions relatively realistic.

Ojai is a geographically isolated but politically and economically diverse community just an hour and a half north of Los Angeles and 20 miles inland from the beachfront community of Santa Barbara. This small city (population 7,461 according to the 2010 U.S. Census) includes funky yoga centers and meditation retreats, a world-class golf resort, and plenty of water-hungry citrus groves carpeting the valley floor and hillsides. The area nurtures a wide range of political perspectives, having long been a magnet for countercultural thinking, and is now increasingly becoming a location for second homes and tourism catering to a wealthier demographic escaping the clogged freeways of Los Angeles (and who many longtime residents argue are, in turn, hopelessly clogging the single road bisecting the valley that leads into and out of town). Several multigenerational farming operations engage in an active citrus growing industry that supports diversity in the valley by attracting a sizable immigrant population to provide necessary labor, but as is the case in much of California, the working class is increasingly being priced out of a rapidly appreciating real estate market. The advocacy group House Farm Workers (2017) estimated there are 36,000 farm workers in Ventura County which includes Ojai, noting that the average annual salary is $22,000 a year while the average rent is $20,000 a year.

On paper, Ojai embodies many of the diverse and conflicting dynamics that make up the Golden State of California. One thing that every resident stakeholder we met seems to agree upon is that Ojai has a culture all its own. The stakeholders just cannot agree on exactly what it is. We deployed Transition Design in the Ojai Valley to try and help them find out.

The Genesis of the Ojai Workshops

The first 2-day workshop introduced the principles of Transition Design and yielded a map of the stakeholder landscape related to water. “Enabling participants to go beyond ‘what is’ and imagine ‘what could be’... the visioning and backcasting segment of the workshop enabled people to think beyond current limitations and glimpse a common future and a pathway toward it” (Irwin & Kossoff, 2017). This proved promising enough to participants (including concerned citizens, business people, artists, and even the mayor) that a second workshop was scheduled to deepen the learning and engage additional stakeholder groups. The second workshop dug deeper into the beliefs and assumptions of the different stakeholder groups while allowing more time to explore the futures visioning processes targeted at reducing conflict while emphasizing areas of synergistic thinking. Together, these two workshops paved a way forward for Transition Design practice by providing a forum and a meaningful case study that tested theories and practices being researched and developed at CMU’s School of Design.

The invitation to hold the Transition Design workshops came from a small group of citizens committed to water security in Ojai who had been catalyzed for action through a lecture given by water expert Tom Ash at the Ojai Retreat in April 2016. During the lecture, Ash identified the unique problem that Ojai faced in terms of water and framed it as a potentially existential threat for the community, citing that they could virtually run out of water in as little as 5 years, prompting a group of concerned citizens to convene at a private home for a dinner to discuss the problem. To help spread the alarm, this group organized another, more widely attended talk, sponsored by the Ojai Green Coalition, that took place on May 26, 2016. They then formed an action committee, The Ojai Valley Water Trust (OVWT), which held its first meeting on August 14, 2016.

The OVWT initiated contact with CMU after a member learned about Transition Design by watching Terry Irwin present at the 2016 American Institute of Graphic Arts (AIGA) National Conference in Las Vegas, and within a short time, they had invited Irwin and Kossoff to facilitate the first workshop on January 27 and 28, 2017.

Reacting to an Emergency by Thinking Fast and Slow

Ash’s 5-year time frame created the sense of urgency that organizers sought to capitalize upon, but this same urgency also makes it difficult for participants to exercise the patience needed to slow down and evaluate the sweeping landscapes of the problem. Understandably, with an active group targeting a potentially existential threat to the community, it has not been easy to temper the group’s desire to rush toward quickly quantifiable solutions that could offer short-term respite but that do not necessarily embody the long-term systems-level changes that Transition Design seeks to engender in order to form more lasting and sustainable lifestyle-based solutions. As noted above and discussed further below, this fundamental shift in thinking to longer-time-frame solution-landscapes remains one of the foremost challenges of the Transition Design practice which is “at odds with 21st century expectations for quick, conclusive, profitable and quantifiable results” (Irwin, 2017).

Nevertheless, this highly motivated and intensively activated group proved instrumental in garnering the support necessary from key community players (from the management of The Ojai Valley Inn and Spa who provided space for the workshops to city council members, city planners, and even the mayor, all of whom attended) and laid the groundwork for two well-received workshops. Although the workshops further catalyzed and inspired this highly activated base, as noted in Irwin’s discussion of the emerging process, the coevolving areas of Transition Design (vision, theories of change, mindset, and posture) that all proceed through a practice of open collaboration and self-reflection, before finally “designing interventions”, means that the practice must be given time, and “results” may not emerge for years or even decades (Irwin, 2017).

In the end, an activist focus and energy proved instrumental in the launching of this initiative in Ojai. Designing tools and tactics for maintaining this activist energy over the extended time frames required for a successful Transition Design practice to unfold -as punctuated as it needs to be with periods of waiting, observation, and research- remains one of Transition Design’s most urgent areas for development.

The Stakeholders Represented in the Ojai Workshops

The two Transition Design workshops, facilitated by faculty from Carnegie Mellon University, were held at The Ojai Valley Inn and Spa on January 27 and 28, 2017, and May 5 and 6, 2017. The initial workshop was attended by a diverse group of committed community leaders; however, they determined that some important perspectives were missing. For the second workshop, the organizers identified and recruited six stakeholder groups (water experts, farmers, environmentalists, business people, politicians, and residents) after noting that water experts’ and farmers’ perspectives were noticeably absent in the first workshop (Irwin & Kossoff, 2017). An attempt was made to include at least one or two genuine members from each constituency, but in some cases (particularly with farmers unwilling or unable to get away from work for 2 days during the busy spring season), a proxy had to be identified. During the second workshop, a homeowner who cultivated a small orchard on his property and a permaculture expert who works with many of the farmers in the valley were asked to contribute the farmers’ perspective as best they could. The perspective these two participants offered benefited from insights gained through small-scale farming and larger-scale consulting engagements with farmers but lacked the visceral intuition of one who has spent a lifetime dancing with the elements while his or her livelihood was at stake. Ultimately, it is believed that in order for a participatory, holistic, systems-based solution-landscape to emerge, stakeholder research must include genuine input from all stakeholders. This input not only informs the derived interventions but including all voices early and throughout the process also helps ensure the buy-in required to successfully sustain the long-term, wide-scale, behavioral, and mindset changes that Transition Design practice hopes to engender within its targeted design intervention landscapes.

An illustration of this occurred several months later at a fundraising dinner for the proposed Transition Design center that was attended by one of the area’s prominent citrus growers. After noting that the farmers had been feeling totally left out of the conversations about water until that evening, he defending the fundraising goal suggesting that “while 150,000 dollars (the projected cost for the first year of a Transition Design center the com- munity was trying to start) might sound like a lot of money” he’d spent nearly twice that on maintenance for his irrigation system this year alone (Workshop participant, August 24, 2017). Unexpectedly but perhaps not surprisingly, a multigenerational farmer, quite familiar with making long-term capital investments, and with a visceral stake in the effects of water shortage and climate change, had no problem seeing the benefits of adopting a long-range view in implementing the changes necessary to overcome the water crisis. His comments at the fundraising dinner provided evidence of the benefit of including all voices in the conversation revealing that support and insight may emerge at any time and from unexpected places.

Another serendipitous example of the need to include all voices in this conversation came at the end of this same dinner after everybody had left and while we were packing up to leave. One of the servers approached and asked about the process we’d been discussing throughout the meal. He said he was a student living in what he described as “a poor community” on the edge of the nearby city of Ventura. He was studying health care in college and hoped, after graduation, to help provide access to better health care to members of his underserved community. He said he was

disappointed that he’d been assigned to work the dinner because he wanted to work outside, [it was a beautiful evening, and the resort has many outside patio dining areas], but now [he was] happy that [he’d] worked the dinner inside because the conversations and the process described was so inspiring (Workshop participant, August 24, 2017).

The goals and inspiration shared by this young man who had accidentally been given a seat at the table provided an inspiring example of the untapped potential of community members often left on the sidelines during attempts to address complex community problems.

The Importance of Stakeholder Engagement at Every Stage of the Process

One surprise during the second workshop was the shortage of participants available to represent the residents’ stakeholder group. Because virtually all participants were residents, it was taken for granted that this group would be easy to fill, but all but one participant fell neatly into other categories forcing us, as with the farmers, to identify a proxy to fill out the residents group. When we, along with the local organizers, assigned a participant to fill this much-needed slot we encountered an unanticipated resentment. It turned out that the chosen participant owned a small business in town, and as the day went on, it became evident that the participant was disappointed not to be included with the business people. This provided an obvious but valuable reminder for the facilitators that participatory practice should extend to all stages of the process, and if you want broad and open participation, even seemingly benign decisions should be made with input from everybody involved.

The inability to field a comprehensive stakeholder base to participate in the workshops was offered as evidence by the organizers that confirmed the need for a next step in Ojai’s Transition Design process that included professional qualitative research to complete the picture and validate the hypotheses and insights the workshops had provided. This research would be aimed at capturing the perspectives of all stakeholders, not just proxies, and would extend well beyond the six broad groups practically identified for the purpose of these workshops. Additional stakeholder groups to include in the conversation about Ojai’s water security should include migrant workers, the less affluent, and indigenous people, three groups whose voices are seldom included in community consensus. Research itself may also reveal other meaningful subgroups whose perspectives should be included. As noted by Irwin elsewhere in this journal, “User and human-centered design approaches seldom have the objective of identifying all affected stakeholders and their concerns” (Irwin, 2017), and developing a framework that insists upon the importance of this objective is emerging as central to the practice of Transition Design.

In addition, these categories were organized for purposes of the 2-day workshop, and participants were asked to dig deeply into sharing a specifically narrow perspective through a variety of lenses and framing exercises. By necessity, we asked them to artificially focus their perspectives for these 2 days of immersive engagement. More traditional qualitative research would attempt to capture a stakeholder’s perspective while embracing all of the nuances of what may well be a multivalued perspective. This further emphasizes the need to supplement these workshops with in-depth qualitative research throughout the community in order to not only gain insights but also to nurture the sense within all stakeholder participants of having their perspective fully heard and held within the context of the Transition Design practice and the interventions that emerge from it.

Including Stakeholders in the Solutioning Process

The perspective of including all stakeholders not only in the identification of wicked problems but also in the development of collectively engaged solutions is leading the Transition Design practice to embrace a variety of approaches from the social sciences that “as yet have not been integrated into traditional design processes” (Irwin, 2017). As shared by Irwin elsewhere in this journal, these include “Participatory Action Research, Multistakeholder Governance, Multi-Stakeholder Processes and Stakeholder Analysis” (Irwin, 2017), and we attempted to include several of these practices in the Ojai workshops.

The second workshop began with each stakeholder group identifying their hopes and fears. A dry erase form was provided to make the process less precious, allowing participants to scribble and erase, refine and rewrite, while preventing the posted canvases from becoming overly messy with crossed-off changes of heart. Some surprising affinities emerged through this process, and it launched the group toward a more empathic engagement right from the beginning. Farmers saw the water shortage and the decimation of their livelihood as feeding a “Loss of Pride” and a “Loss of Identity.” Residents, who had expressed frustration at being asked to ration water when oft-cited statistics show that 80% of it goes to agriculture (Guo, 2015) expressed fears that the water shortage would lead to a loss of “Community Identity” and also shared a fear of a “Loss of Agriculture.” These residents’ insights indicate a shared vocabulary with farmers by emphasizing “identity” and reveal a fondness residents feel toward their agricultural neighbors that had not surfaced during previous public discourse. We hope that this was made possible thanks to safe boundaries created by the structure of the workshop exercise.

At the heart of Transition Design practice lies a firm belief that wicked problems will be solved only through collective action. These small wins in which affinities are revealed begin to bridge conflicts that stand in the way of multistakeholder interventions. Identifying, modifying, and further developing tools that facilitate empathy and cooperation between stakeholders with potentially differing agendas, whether borrowed from the social sciences, the political sciences, or elsewhere, is an important priority as the Transition Design practice continues to be developed.

Identifying and Dealing with Stakeholder Group Biases

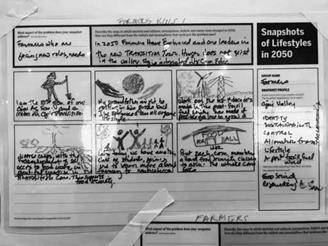

Of all the biases revealed by the activities during the second workshop, one of the starkest emerged during efforts to imagine lifestyles in a water-secure world some three and a half decades into the future in 2050. The primary motivation behind framing the exercise around lifestyle-based visions of the future is a belief that this allows participants to distance themselves from current technological solutions and their expected outcomes. Placing the vision sufficiently far into the future during such exercises also seeks to decouple the imagined outcomes from a direct causality resulting from actions taken in the present. (Of course, the ultimate goal is action in the present, but the goal of our workshop activity was to backcast into present-day activities after first separating ourselves from them, a process that is discussed further below and is discussed by Irwin (2017) elsewhere in this journal.) The water experts who clearly felt an ownership of the problem being explored and embodied such a deep and visceral technological connection to it found it was extremely difficult for them to steer clear of precisely the kind of one-off, technologically focused, results-oriented solution that Transition Design hopes to transcend. During this exercise, they clearly had the most difficult time of any of our stakeholder groups separating their thinking from a vision where the technological infrastructures they currently advocate had all come to pass and brought about the water-secure future of our dreams. Who can blame them? They spend their days designing, advocating for, and implementing precisely these solutions.

In an effort to free up their thinking and immerse them more in the spirit of the activity which we had hoped would generate real and inspiring flights of fancy, we encouraged the water experts to imagine themselves stopped on the street regularly for selfies with local residents who regarded them (appropriately, one would argue) with the reverence normally accorded to rock stars and Emmy-winning actors rather than public works managers. They found this amusing, and perhaps even appealing, but remained mired in their perception that if the community just gave them enough money and got out of the way their technological fixes would bring about a world where everybody flushes their toilets regularly and often before walking barefoot across a lush green lawn and slipping back into their solar-heated swimming pools.

Perhaps these water experts are simply too accustomed to dealing with infrastructures, projects, and planning that are already executed within timelines of decades, and thus, the future we sought was not far enough out to shift their thinking. However, alas, their vision of the future stemmed almost entirely from the realization of technologies, a desalination plant, a connection to the state water supply, and the increased availability of recycled water, which have already been proposed, all of which would take decades and tens of millions of dollars to implement, and none of which consider the impact of changing stakeholders’ mental models of how water is woven into our lifestyles and habitual behaviors. One could even argue that by focusing entirely upon the supply side of the equation the solutions dreamed up in the engineering and infrastructure-oriented minds of the water experts merely give permission for status quo mindsets to be perpetuated.

This in no way suggests that Transition Design practice rejects or belittles expertise and technological development. Instead, the developing practice emphasizes that complex system interventions require solutions implemented on multiple levels of scale and time frames and with varying degrees of technological expertise working in concert (see Irwin’s discussions of the Winterhouse social pathways matrix and the power of “linking and amplifying projects” elsewhere in this publication; Irwin, 2017) so that a solution landscape emerges that imagines behavioral and mindset changes that provide a more sustainably powerful landscape within which engineering and technological breakthroughs and implementations can be deployed. Developing the tools to overcome an expert mindset with in the context of a Transition Design practice that proposes nonexpert approaches to nurturing multistakeholder contributions to solutions, and holds paradigm shifting mindset adjustments at its core, remains a daunting challenge, but nowhere is it more evident than in learning to engage with the input of experts without being swept into the comfort of a belief that a technological silver bullet lies tantalizingly just beyond the horizon.

Affinities Mapping and Collective Visioning Smooths Over Conflicts

While the first workshop was executed largely using traditional Post-it note paste-ups, feedback and reflection afterward revealed a few problems with this method. Although the practice is common for this type of workshop, “participants tended to write single words that had meaning for them in the moment, but were not clear to other participants and provided a fragmentary/cryptic record” (Irwin & Kossoff, 2017). In addition, some participants, unfamiliar with the challenges of working in settings that demand fast-paced creative output, were unclear about or intimidated by the exercises. Consequently, a good deal of effort went into preparing canvases for the second workshop that provided instructions, examples, and structure for the exercises (See Figure 1). The canvases were laminated and dry erase markers provided, giving participants the ability to write and erase with impunity as they brainstormed and refined their visions and responses. (An unintended consequence of these dry erase canvases is that they introduced a need to vigorously police the presence of permanently marking Sharpies during the 2 days. A distraction the organizers would have gladly done without!) Overall, however, the gambit paid off with rich and detailed input from virtually all participants, and we attribute at least some of this to the freedom to erase,

Figure 1 Based upon feedback provided from the first workshop, Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) facilitators provided more structured dry erase canvases that made the exercises and outputs clearer for participants.

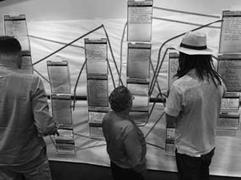

Figure 2 Using paper tape instead of string to identify connections between different stakeholder canvases allowed participants to annotate their connections amplifying the communication between groups.

rewrite, and refine, the clear examples allowing participants to better understand what was expected and the structured framing for the output of every exercise that was provided by the canvases.

Throughout the second workshop, participants were asked to post their work by taping the canvases on the wall in a manner that allowed them to draw connections and conflicts between different groups using paper tape and markers. This method provided an effective way to get them working together between groups and began the process of building empathy for their varied perspectives. The lack of pin-able walls forced us to provide paper tape to draw the links, and although the classic tacks and string might have been less messy, allowing connections to be made via less circuitous routes, the paper tape afforded participants the added ability to annotate the connection providing additional context for the links they had discovered (See Figure 2). In practice, although the tape proved slightly awkward, it actually helped defuse the potential for tension created when conflicting perspectives were posted, helping generate a more playful and cooperative environment. At each phase of the process where canvases were posted and the group asked to collectively search for connections and conflicts, positive energy flowed in the room, and the bonds of community became more evident as these conflicting stakeholders were forced to work together to look for connections and find routes for their web-like paper tape pathways (See Figure 3).

Figure 3 The canvases and tape provided ample opportunities for workshop participants from all backgrounds to work cooperatively identifying connections and conflicts. Many connections between hopes and fears were identified.

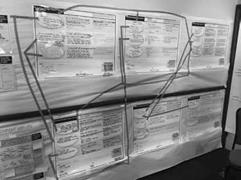

Figure 4 After the workshop in which participants explored future visions framed around lifestyles, the participants’ backcasting process revealed many alignments between the proposed steps on a transition pathway toward a watersecure future. (Green tape indicates alignment between proposed projects.)

Backcasting Toward Desirable Futures

The final exercise of the Ojai workshops provided a critical bridge from theory and research toward action within a context that places proposals into a landscape benefitting from contributions by all stakeholders. Building upon the power of imagining future lifestyles to enable jettisoning current or expected solution trajectories, backcasting seeks to shift perspectives from what is likely to happen to ways in which what is desirable to happen might be brought about. Irwin (2017) quoted Robinson: “the major distinguishing characteristic of backcasting analysis is a concern, not with what futures are likely to happen, but with how desirable futures can be attained”. Thus, workshop participants were asked to “create a transition pathway from the present to their 2050 vision and use post-it notes to speculate on what projects, initiatives, and milestones would be necessary (between the present and 2050) to achieve the vision” (Irwin, 2017). By focusing on lifestyles instead of specific solutions, a surprising amount of synergy between the future visions of each stakeholder group emerged. During this final exercise, we asked each group to provide three possible present-day solutions leading to their envisioned future and five of the six groups proposed an educational initiative (See Figure 4). Meanwhile, politicians recommended policies to incentivize water-conscious building practices and planning that seemed totally aligned with the requests of environmentalists to develop water-conscious neighborhood team projects (which could be addressed with building projects) while also asking for changes to the way stormwater is handled (addressable through planning policies).

In Summary: From Hopes and Fears to Future Visions

Identifying their hopes and fears revealed many conflicts between stakeholders but also identified many affinities between groups that community members had previously characterized as at odds. Developing narrative visions of future lifestyles and then backcasting into present-day initiatives even further revealed how much potential cooperation there was. “Transition Design proposes backcasting as a collaborative activity in which stakeholder groups can leverage their visions of desirable futures to inform tangible, consensus-based action in the present” (Irwin, 2017). We believe that further research will show that although many conflicts within communities emerge when discussing solutions-based approaches to complex problems, by slowing down the process and shifting the conversation away from specific solutions toward lifestyle narratives more synergy of perspective will emerge. During the workshops, by pushing the mindsets well into the future and framing goals through the lens of lifestyle, we found that contentions began to melt away, and more alignment emerged. From the politicians’ belief that “it’s our water, not my water” to the residents’ belief that “access to clean affordable water is a basic human right”, and from the farmers’ belief that “food and water basic rights will be proven in courts” to the business people’s belief that “water will not be a commodity”, it was clear that, stripped of a need for specific solutions about how to get there, a heartening amount of synergy existed across all stakeholder groups around the importance of celebrating water not as a business commodity for trade but as a basic human right.

Final Reflections on the Workshop Experience

At the end of the final day of the workshops, time was taken for all participants to share their experience and what it meant to them and what they felt it meant to the Ojai community. One long-time resident noted that the open dialog engaged in during the workshops “felt like the old days” in Ojai and went on to lament that so many of the issues currently being faced, such as the water shortage, short-term vacation rentals, and a more transient population, were being handled with rancor and personal attacks through the impersonal communication threads of Facebook groups and Twitter. She missed the days when Ojai’s relative isolation made it feel more communal and interactions often took place on the streets with a powerful sense of belonging and place. Another participant hoped that this practice could not only help Ojai achieve water security but would also build ongoing communication channels that could ease tensions around zoning, development, and sustainable city planning initiatives. These sentiments of what could only be described as relief surrounding the civility and openness of the conversations that had taken place during the workshops were echoed again and again throughout the room.

Clearly, the participants emerged with a sense of optimism about the practice, and many wondered what the next steps could be, hungry to take the process further, and recognizing that the workshops were only the first step toward the participatory community practice of Transition Design that had been modeled. In final summary remarks, Irwin emphasized what had been repeated throughout the four days of the two Ojai workshops.

That these workshops were models of Transition Design developed to introduce the practice to the community and for them to evaluate the process to see if they thought it could take hold in their community and start Ojai on a long-term transition process toward sustainability through stakeholder equity and participatory design practices. The next step ideally would be to conduct research to validate the findings surfaced in the workshops, broaden the scope of insights, and ensure that all stakeholder groups within the community are represented. Efforts are now under way to fund a full multistakeholder research project throughout the Ojai Valley focusing on issues surrounding water security.

How to Sustain an Em(Urgency)

Inspired by the experience in these workshops, one group also decided they would try to raise money and start an Ojai Transition Design Center (OTDC) in the middle of town that would not only pursue a water-secure future, but that they hoped would also inspire the community to embrace the ethos and practice of Transition Design as integral to the cultural fabric of Ojai and implement it to solve a wide range of ongoing issues that have fueled contention between resident stakeholders.

One of the biggest hurdles to establishing the OTDC is developing leadership within the community to sustain such a long-term initiative committed to slow change. Ojai has several charismatic and passionate individuals who have rallied around issues ranging from preservation to environmental protection and education to tourism. Nevertheless, most remained on the sidelines despite expressing interest in and support for the process. One community member who participated in both workshops and played an active role helping to organize them shared that her spouse, who has spearheaded several successful grassroots initiatives in the past, is “an activist, he can’t really see how he’d fit in to this process” (Workshop participant, September 21, 2017).

This perception emerged regularly throughout the process in Ojai inspiring the title of this section. It represents one of the biggest challenges facing any process targeting complex systems change. How do you create and maintain an activist’s sense of urgency for a problem landscape requiring multiple interventions and operating over years if not decades? Boyer, Cook, and Sternberg (2010) of the Helsinki Design Lab reminded us that you should “never waste a crisis”, and Ojai’s water shortage has motivated a committed group of people and policy makers to begin taking action to solve this particular one. As the practice matures, we need to help them stay focused by identifying multiple stages and targeted intervention points to help maintain a sense of engagement with the process. We need communications that highlight multiple milestones of accomplishment and break the process down into regular small wins that will keep enthusiasm for the process alive and maintain the urgency and engagement of personality types who are drawn toward activism and leadership but whose very strengths as leaders render them prone to boredom or burnout when the measurements of success are neither obvious nor certain.

Having engaged with the Ojai community over the past several months through the second workshop and helping to weave Transition Design into the fabric of the community while laying the groundwork to launch the Ojai Transition Design Center, it has become clear that one of the most pressing concerns facing those of us interested in enacting systems-level change over protracted time scales is developing communication tools and motivating activities that can sustain the passionate urgency of activism while engaged with a process that requires infinite patience, long periods of study and reflection, and decades of persistence. For now, I leave you with the mission statement of the yet-to-be-launched Ojai Transition Design Center.

Mission Statement of the OTDC

The Ojai Valley faces a variety of challenges affecting the community’s daily needs, and long-term solutions, hampered by the area’s conflicting social and bureaucratic ideas and ideals, have been difficult to come by. Problems like water use and the drought, affordable housing, education, and transportation are multifaceted; they cannot be solved with typically designed solutions. They can be unlocked only by changing the culture in which these complex problems emerged.

Transition Design targets these problems through a practice that encourages all those affected to participate in developing a culture that nurtures solutions. Using this approach, the Ojai Transition Design Center (OTDC) will foster the emergence of newly sustainable attitudes in Ojai by provoking thoughtful conversations and facilitating innovative engagements that cumulatively lead to long-term, broad-based, deeply-rooted change throughout the community.

The OTDC will be a safe and collaborative space, holding workshops and activities that help the citizens of Ojai talk about the issues and reveal underlying consensus that can lead to lasting change. The center will also perform research and outreach that enable contribution by stakeholders who do not normally have a voice in solving problems within the community.

The primary goal of the Ojai Transition Design Center is to make sure that everyone in Ojai has a voice addressing these complex challenges and that the conversation proceeds sustainably, inclusively, and respectfully for all.