Introduction

The paper presents an interdisciplinary study aiming to investigate the potential of Design to support youth development and promote the culture of sustainability in the transition to adulthood. The research is currently in development within the scope of a Ph.D. project. Preliminary work at a Master’s degree level provided a foundation for this study, indicating potential areas and guidelines for designbased interventions in those fields. We start by presenting a theoretical background, which connects the societal transition towards sustainability, the youth in transition to adulthood and the potential role of Design interplaying with those transition processes. Then, we present the preliminary results coming from the exploratory phase of the PhD research.

Transition to sustainability: crisis and opportunity

In the current socio-economic-environmental context, we live in a time of crisis, in which the model of growth and organization of material life has become incompatible with natural resources and with the support of life on the planet. We are now facing fundamental issues concerning the balance of natural and cultural systems and quality of life as a whole. The current concept of well-being is related to the search for immediate gratification of individual interests (Brown, 1981) and the minimization of personal involvement (Manzini, 2008); the sense of care and belonging and responsibility for the collective is being increasingly diluted (Augé, 1994), and a widespread consumption mentality has been reinforced. This crisis affects especially the younger ones, who may have difficulty to find valid paths to develop themselves and find their role in society, in an increasingly complex world.

On the other hand, as in any context of crisis, there are also immense possibilities of advancement and change (Morin, 2001): the same material bases that underpin the current system can serve to other objectives and create a new story, if we use the system as from alternative forms of action (Santos, 2000). Morin (2001) observes the emergence of several “regenerating countercurrents”, which bring multiple possible foci of transformation: (a) the ecological countercurrent; (b) the countercurrent for quality of life; (c) the countercurrent of resistance to purely utilitarian prosaic life; (d) the countercurrent of resistance to the primacy of standardized consumption; (e) the countercurrent of emancipation from the ubiquitous tyranny of money; (f) the countercurrent that fosters the ethics of peace.

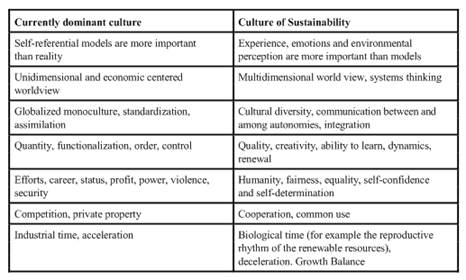

Collaborative projects and new reflections emerge, mapping challenges and opportunities in different contexts, and outlining possibilities of action and innovation for a transition towards sustainable lifestyles and new contexts. We witness the emergence of creative communities and collaborative organizations seeking alternative solutions (Manzini, 2008; Meroni, 2007). In several countries, initiatives that seek more responsible and ethical alternatives are being developed, such as conscious consumption, solidarity-based economy, voluntary simplicity, liability for waste and clean production, alternative energies and ecological construction, development of agroecological systems, food security, among others. The present study concerns the social and cultural dimensions of sustainable development, focusing on the transition towards sustainability as a process of social learning, reflecting the need and centrality of a cultural shift in how individuals and society approach economic, social and environmental issues (Duxbury & Gillette, 2007). The culture of sustainability encompasses key ideas and values that are fundamentally different from the core values underpinning the currently dominant culture (see table 1, Brocchi, 2010).

Table 1 Core values in the currently dominant culture vs. core values in the culture of sustainability.

In this current context, we emphasize the importance of invest to promote a culture of sustainability among youth, fostering the creation of new scenarios and lifestyles, strengthening critical thinking, autonomy, ability to make choices, and innovative mindsets and practical paths. It is especially regarding the new generations that the changes towards healthier, integrated and sustainable lifestyles are fundamental.

Young people are the core of our present and the key scene for questioning if there will be a future (Canclini, 2007). The young person carries in him/herself, in an intensified way, the problems of our civilization: youth is simultaneously the weak link (for its weak sociological insertion) and the strong link (for its energy) of our society (Morin, 2012). In a brief future, this generation will need leaders and citizens who think ecologically, understand the interconnectedness of human and natural systems, and have the will, the ability and the courage to act (Stone, 2009). The ability to understand and seek meaning on the experiences and choices will be a key attribute for young people in this process. The transition toward sustainability implies changes in behavior resulting from a process of awareness, collective accountability, belonging and strengthening of autonomy.

Youth: life in transition

Constituting a transition phase by nature, youth is characterized by the desire to experience different identities and different ways of living, in order to accomplish their existential motivation: the constitution of identity (Erikson, 1968), the search for understanding themselves and developing a meaningful role in the world. After transitions in various levels (biological, cognitive, psychological and social) lived during adolescence (Steinberg, 2007), the young person lives a process of social and interpersonal redefinition and must assert his/her autonomy. The challenges of this transition consist in shifts in relationships with parents, exploration of new roles, continuing the process of identity formation at social and personal levels, planning on the future and taking steps to pursue it (Gootman & Eccles, 2002).

Adolescence and emerging adulthood are social constructions, consisting in relationship-based identity development processes, in which the interpretation they make of them-selves and their worlds is essential (Nakkula &Toshalis, 2006). The young person experiences various ‘possible selves’ and an increasing sense of self-understanding and under-standing others (Santrock, 2014), leading to the development of a renewed self-concept and to a broad process of changing roles and modes of interaction.

Important transitions in cognitive aspects also take place during this period, including the improvement of the young person’s competencies for decision-making, critical and creative thinking (Steinberg, 2007). The cognitive structures of emerging adults are still developing; several brain pathways are strengthening, which allows for greater processing of emotions and social information, sense of self and capacity for self-reflection (Beck, 2012; Arnett, 2014). The most advanced cognitive processes, including practical, flexible, and dialectical thinking, characterize this stage (Berger, 2008).

Since the transition to adulthood is marked by a shift from relying on external authority to taking ownership and responsibility for one’s life, young people need to be exposed to experiences and receive support to develop more mature ways of making meaning and capacity to make internally based decisions (Baxter Magolda & Taylor, 2015). Capacity Development for the Transition to Adulthood is one of the three axes of the Operational Strategy on Youth 2014-2021, proposed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, 2014).

Promoting empowerment in this period has significant benefits for young people, including healthy identity experimentation, gains in confidence, critical awareness, self-efficacy and selfesteem (Chinman & Linney, 1998). Empowerment is then a decisive factor, providing opportunities for youth to build capacities and prepare themselves to face the challenges in this transition and constitute a future development plan. Youth empowerment is also closely linked to the processes of social change towards sustainability, at the extent that it fosters autonomy, collective responsibility, skills to deal with complexity, and prepares youth to actively participate in sustainable transformations in society. Involving youth in programs on cultural and social dimensions of sustainability can help provide them with a more optimistic outlook on the future and proactive behavior in the present (Duxbury Gillette, 2007). Youth developmental outcomes play an important role in the effort to promote sustainability: when youth gain skills in these areas, they are well situated to serve as leaders in community-wide sustainability efforts (Browne, Garst, & Bialeschki, 2011).

Higher Education may play a significant role in these processes: universities have great potential to constitute positive environments for students’ growth and empowerment. The processes of purpose-driven career exploration and development of awareness and competences in sustainability are key developmental opportunities in the transition to adulthood.

Design for transition(s)

Increasingly considered as an integrative discipline, a strategic approach, and a catalyst for change, Design offers a range of potentialities and interfaces for innovative action in diverse areas. Design principles and practices are being applied as tools to understand reality, formulate problems in new ways and develop solutions that emerge from a collaborative process (Cassim, 2013; Cross, 1982; 1999; Krucken, 2008). The present study is situated among those emerging approaches aiming aims to understand the broad context of the activity of Design, its interconnections with the social reality and its potential to propose innovative solutions interacting with other fields of knowledge.

In the transition towards a culture and a sustainable lifestyle, Design is a potential agent of creative innovation. Intrinsic characteristics of Design can contribute to solve the issues of our time: interpretative richness and visionary ability (Krucken, 2008), as well as skills of thinking systemically and the inventiveness of language (Cardoso, 2012). Networks of multidisciplinary action are being developed, in which designers contribute by developing tools, infrastructure, equipment, but also processes, networking, mediation and creative collaborative solutions (Landry, 2012; Malaguti, 2009).

In search for alternative modes of inquiry and intervention in the field of youth development and engagement in sustainability, Design shows promising characteristics, such as:

a) focus on applied and creative knowledge; (b) combination of distinct yet interacting cognitive processes; (c) continuous engagement in evaluation and reflection; (d) development of concepts on multiple fronts in real context; (e) systemic vision and ability to communicate possible futures; (f) use of visual languages and integrative and collaborative team-based approaches; (g) focus on human values and empathy (Cross, 2006; Banerjee 2008; Owen 2005; d.School 2010; Schon, 1987; Buchanan, 1992).

Participatory approaches in Design emerge as strategies particularly suited to promote empowerment during the transition to adulthood. The origins of Participatory Design date back to movements toward democratization at work in Scandinavian countries in the 1970s (Ehn, 2008). The field has since expanded in scope and methods, gaining widespread acceptance as an approach to practice in research and application across design areas and other interdisciplinary fields (Martin & Hanington, 2012). Participatory Design research is currently exploring new ways to facilitate participation, change and development in diverse areas, with new forms of participation arising, such as open and user-driven innovation; living labs, fabrication labs and open production; tools for public participation and social innovation (Bannon & Ehn, 2013). Coming from a democratic tradition and supporting process of mutual learning, these processes are also well positioned to support innovative approaches to human development and social change.

Co-design activities encourage systems thinking; encourage people to be active participants and suppliers of solutions; reveal new ways and possibilities of doing things; and strengthen the sense of trust and mutual growth (Sanders & Stappers, 2008). Participatory design processes can contribute to youth development in several levels, due to the importance of developing participatory skills of different natures; it can also be a powerful way to uncover and mobilizing capacities for creative and collective problem solving (Kafai & Peppler, 2011; Frandsen & Petersen, 2012).

Methods

The research investigates how the integration of Design cognition and design-based collaborative practices into learning experiences in Higher Education can promote youth empowerment and engagement in sustainability. Design methodologies will be applied in two main axes: (a) as a way of knowing and inquiring: design mindsets will be applied as a way to understand the issue at hand, investigate and frame the problems, devise strategies for solution and develop an innovative approach to the question; (b) as an applied activity: co-creation design activities work both as an strategy to raise information during the exploratory phase and as a way to develop collaborative solutions during the intervention phase. The research design comprises a composition of quantitative and qualitative research methods, using both traditional and emerging approaches. The choice for a mixed-method approach is justified by: (a) the variety of issues involved and the complexity of the research question; (b) need to integrate different experiences and seek points of convergence around the object; (c) possibility to validate constructs from interdisciplinary areas through a multi-method perspective.

The preliminary phase of the research was developed at Master’s degree level and the current phase is in-progress, being developed in the context of a PhD degree. The audience is college students between 18-25 years, and the focus is on the development of empowerment as a key aspect of youth’s engagement with sustainability in the transition to adulthood. This paper presents initial findings of the exploratory phase of the study, which involved:

(a)an interdisciplinary literature review; (b) analysis of context in the light of theoretical works in youth development, youth cultures and Design; (c) ethnographic observation; (d)application of design-based activities in three undergraduate courses, in Brazil and in the United States.

Preliminary Results

The initial results include an innovative theoretical framework for youth empowerment, considered as interplay between internal individual experiences of development and external collective lived experiences of development. The fundamental dimensions of youth empowerment would be agency, sense of purpose, youth-adult partnerships and meaningful participation in community (Mouchrek & Benson, 2017). In this conception, empowerment does not constitute an inherent trait or a process external to the individual, but it develops actively with the individual in context.

Preliminary results also show that Design is a promising methodology for intervention: as a way of knowing and inquiring (research, experimentation and analysis guided by Design allow substantial progress in understanding the issue) and as engaging activity (design-based activities offer excellent opportunities for positive action). Ethnographic observation and co-creation activities were developed in order to gather initial information and pilot the application of design techniques with the target audience, in the context of three undergraduate courses, as follows.

1.In a design laboratory course focusing on open innovation in sustainability (UEMG-Brazil) with 20-25 students, a co-creation activity focused on students’ perception of youth and their context of development (What means to be young nowadays? What is the spirit of our time?). Using design tools such as ideation, affinity diagramming and visual maps, students’ groups created collective image boards (See Figure 1). The whole group engaged in structured reflection and produced a synthesis map. The visual maps drawn up at the beginning of the process led to the emergence of an active debate among the students, who have shown interest, willingness to express their views, and built in collaboration a complex profile of issues related to young people´s reality and potential intervention based in Design (Mouchrek & Krucken, 2014).

2.In the scope of an interdisciplinary introductory course on sustainability (Virginia Tech-US), two co-creation activities were developed (See Figure 2). The first activity included approximately 60 students and prompted them to reflect about their values and create projections for the future (What inspires me? Who is my future self, 5 years from now?). Using ideation, group discussion, scenarios and video, students revealed interesting intrinsic motivations and proposed diverse future trajectories, both personal and professional. The group shared insights about the relevance of starting to pursue strategies in the present in order to create conditions for the future contexts they designed for themselves. The second activity happened with the second iteration of the course and asked a group of 20-25 students about their visions and potential strategies on sustainability (How to bridge the valueaction gap in sustainability?). Using affinity diagramming and synthesis maps, students vocalize their perceptions, criticism and envisioned solutions. The activity was considered an efficient way to summarize the content knowledge constructed in the class during the semester and exercise students’ critical thinking on the subject.

3.Within an interdisciplinary course in ideation for innovation (Virginia Tech-US), a co-creation activity (See Figure 3) asked student to provide their own collectively constructed definitions of innovation and reflect back to their developing projects (What is innovation nowadays? Are our projects addressing innovation?). Using image boards and mind mapping, students groups worked to create a collective synthesis map of innovation and potential design strategies to address the dimensions of innovation as they proposed (Mouchrek, Baum & McNair, 2016). The exercise was particularly useful to decrease the

students’ level of uncertainty regards open projects and to allow for their critical appraisal of their own projects, leading to pivoting in many of the projects.

The study is currently piloting a data collection about empowering experiences in college through an online survey, involving students in both United States and Brazil. The current steps aim to contribute to support the theoretical framework developed and inform the proposition of a participatory design-based intervention. An interdisciplinary lens is proposed in order to connect these diverse areas of knowledge.

Discussion

The analysis of context and data gathered was developed in the light of theoretical works in youth development, youth cultures and Design. Conclusions and insights from the preliminary work at the Master’s level also contributed to the analysis. Preliminary results show that Design is a promising methodology for intervention in the field in question, contributing to: developing critical thinking to analyze complex problems and find innovative solutions; providing fields of experimentation for students’ own resources and motivations; offering a range of tools and forms of intervention they learn collaboratively to select and apply; developing concrete and action-oriented projects; and establishing a dynamic system, in which the impact of actions generates a mechanism of feedback and confirmation, that nourishes and stimulates new cycles of project and applied action (Mouchrek, 2014).

Collaborative Design activities aiming to develop empowering experiences for youth are suited to foster their development and engagement in sustainable change, at the extent that they promote several key processes, as follows:

- Students’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivations to participate. Importance of creating environments for young people to define their own motivations and drivers for action. Design techniques are promising in building environments conducive to develop intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.

- Critical thinking and collective construction of knowledge. Participatory design processes can provide spaces for structured reflection, teamwork and social interaction in a non-serious, playful environment.

- Perspective taking and dialectical thinking. Design techniques to visioning and enacting (Brandt et al, 2013) may lead students to experimentation of different identities and value systems, advancing their perspective taking skills and understanding of the various facets of a situation. It can also be a good opportunity to address issues related to social justice and other issues of social concern.

- Equitable power sharing between youth and adults. Design projects with young people as equal stakeholders are promising strategies to support youth development and empowerment. Research shows that youth participants are positively affected by power sharing and dialogue with adults in the design process (Iversen & Smith, 2012)

- Engagement with public space and peer community. Participatory processes can improve youth’s ability to understand and contribute to (trans)forming their life contexts, exercising skills for protagonism and positive intervention as co-creators of public space (Frandsen & Petersen, 2012).

The application of design-based approaches to youth development is particularly promising when it follows aspects such as:

- Incorporates youth language and references. Make sure to provide students the opportunity to express and communicate using text and visual languages from their own frames of reference. Ownership is an important aspect of these participatory processes.

- Proposes visioning exercises that allow youth to create scenarios for future pathways in life. As a support of purpose-driven career exploration, tools of creative visioning may be used for students to project possible future contexts and to map the trajectory of a young person and her/his future development. In small groups, young people could collaboratively develop future scenarios and reflecting about preconditions and discussing decisions, consequences, and outcomes.

- Create opportunities for them to turn ideals and potentials into concrete projects. Ensure that some of the collective ideation developed by the students actually become a concrete application. Design-based activities are especially suited for this purpose. Create specific goals around local challenges and social issues that the group itself identify and create a support for practical action in connection with local partners and other stakeholders.

Final considerations

Young people often present positive and promising interests and characteristics that can be supported and encouraged, such as: motivation to creating innovative practices, desire to participate and to belong, aspiration to autonomy and a meaningful personal and professional life. Design-based activities may facilitate processes of convergence that encourage youth to transform their ideas for change into real alternatives. We must invest in the formation of the new generations to constitute a righteous consciousness of its place and role in society. It is a goal oriented to the future and will define the course of this society.