1. Introduction

During the college years, students navigate the complex transition from adolescence to adulthood. Developmental challenges in this stage of life involve identity formation, setting life goals and undertaking career exploration and development. The capacity for self-directed decision-making fosters a healthy and successful transition to adulthood. Interventions that support youth development at this age benefit from approaches and techniques suited to stimulate reflection, participation, collective construction of knowledge and peer mentoring.

From its origins investigating the design of technology in the workplace, in the last decades, participatory design has expanded in scope and gained acceptance as an approach to practice and research in other fields. In this study, we investigate the application of the theory and methods of participatory design to support youth development in the transition to adulthood, focusing particularly on college students in the process of career exploration.

Choosing a course of university studies and defining a career orientation are central challenges for incoming college students. Within the United States, increasing numbers of students struggle with undecided or changing majors, with reports of stress and anxiety related to this process. The process of career exploration and development is closely linked to developmental aspects such as identity formation, self-reflection, agency and sense of purpose. Supporting students’ development and maturity is needed for helping them to successfully explore and choose their career path.

Offering opportunities for students to collaborate in those reflections, through creative exploration and applied peer support, Participatory Design emerge as a potential innovative approach for interventions aiming to support career exploration in college. The present research extends the application of participatory design facilitation methods in the context of higher education, aligning with university principles of student whole development, and design methods for social good, wellbeing, and healthy development.

2. Theoretical Framework

Youth development

The life period between adolescence and adulthood is marked by developmental challenges, but also constitutes a time of opportunity for establishing positive self-identities and shaping personal futures, both personal and professional. Fundamental changes during adolescence across multiple domains (biological, cognitive, psychological and social) instigate a process of social and interpersonal redefinition characterized by increasing levels of autonomy (Steinberg, 2007). Completing education and entering in the job market are two major milestones common to this phase.

In the past decades, the concept of Emerging Adulthood in industrialized societies as an identified developmental era with a focus on ages 18-25 (Arnett, 2007, 2014). Demographical shifts and changing social and institutional structures in late modern western societies contribute to the emergence of this distinct period of the life course. Young people have an extended period (‘moratorium’) for exploration of possible life directions before taking adult commitment (Arnett, 2007, 2014).

Although the array of life alternatives available to emerging adults has expanded, the collective support for identity formation has decreased (Côté & Levine, 2002). Identity development and the exercise of agency emerge as fundamental processes in negotiating the passage to adulthood (Schwartz, Côté & Arnett, 2005). Important transitions in cognitive aspects during this stage (Steinberg, 2007; Beck, 2012) enable increased capacity for self-reflection and development of a personal philosophy.

Experiences of empowerment that surround the emerging adult have important contributions to development. Because emerging adulthood is a highly volitional era (Arnett, 2007), room for experimentation and choice helps to navigate the course toward adult commitments and roles. Promoting empowerment in this period has significant benefits for young people, including healthy identity experimentation, gains in confidence, critical awareness, self-efficacy and self-esteem (Chinman & Linney, 1998).

Life goals and career exploration

Empowerment experiences during emerging adulthood have potential to advance two key challenges in emerging adulthood: the definition of life goals and exploration of career paths. These practical, short-term outcomes of life goals and career track also carry possible long-term impacts. Facing career choices raises questions about the meaning attached to one’s sense of purpose, priorities, and lifestyle decisions (Bernard, 2014). In the process of defining life goals and career choices, self-authorship and meaning making are central. Because the transition to adulthood is marked by a shift from relying on external authority to taking ownership and responsibility for one’s life, student empowerment experiences lead to more mature ways of making meaning and personal capacities for decision-making (Baxter Magolda & Taylor, 2015).

The process of career exploration may be considered an interplay of a person’s autonomous planning, on one side, and relational experiences on the other side. The successful integration of these twin processes culminates with future roles in society (Maree & Twigge, 2016).

In this study, we approach career exploration as a two-fold process: (a) in the first stage, more general, students are invited to reflect about their life goals and future selves; (b) in the second stage, more specific, the group works together to explore potential career choices and how individual characteristics, goals and plans interact with their alignment with community and the role they want to play in society.

Participatory Design

Participatory design is a qualitative research methodology within a constructive frame-work working both as intervention (understanding and solving problems in context) and as imagination (exploring possible futures) (Bratteteig, 2016). Techniques include design-driven activities for reflection, expression, and sharing (Sanders, 2008).

Following the general evolution of perspective in the design field, participatory design has expanded in scope and methods, gaining widespread acceptance as an approach to practice and research across various fields (Martin & Hanington, 2012; Buchanan, 2001; Cassim, 2013). With the potential to engage people in meaningful and purposeful adaptation and change (Sanoff, 2007), participatory design presents a promising strategy for the research and development of solutions in the field of youth development and empowerment.

Considering the importance to develop agency and a sense of purpose in emerging adulthood (Mouchrek, 2019), participatory design offers settings for expression of youths’ own motivation and drivers for action. Engaging in participatory processes allows for creativity and intrinsic motivation.

Design processes with equitable power sharing between youth and adults support autonomy and empowerment. Participatory design projects that have young people as equal stakeholders are promising strategies to support youth development, because it fosters a key empowerment process: stimulating youth to gradually engage in, control their processes and cultivate constructive change (Cargo et al., 2003). Participatory design also encourages engagement with peer community, uncovering and mobilizing capacities for creative and collective problem solving (Iversen & Smith, 2012; Frandsen & Petersen, 2012). Applied participatory processes establish a dynamic system, where the actions generate feedback and confirmation from peers, which nourishes and stimulates new cycles of action (Mouchrek, 2014).

Participatory design processes can provide spaces for experimentation. Reflection in context potentially fosters the development of more complex meaning making process, providing students with new and improved options for interpreting their experiences and navigating their environments (Baxter Magolda & Taylor, 2015). In this process, it is essential to offer opportunities for students to collaboratively reflect and work to envision possible futures, in multiparty collaboration processes, in which they are not only informants but also partakers in the design process (Mouchrek & Tatar, 2018).

Participatory design facilitation constitutes then a very appropriate method for the present study, since it aims for an in-depth understanding of students’ experiences and identity, capturing their visions about career exploration, intrinsic motivation and perspectives.

Existing projects

Interventions supporting career exploration are usually carried out by career advisors and counselors. Although the field has developed some innovative approaches in the last few years (including constructivist approaches), the majority of techniques still remain centered around an expert advising a novice, usually in one-on-one sessions. This study is motivated by the idea that developing a participatory process involving multiple students working together to explore potential futures and envision career paths can complement traditional career advising approaches.

Our approach seeks to build on insights gained from related areas of inquiry where participatory design is used as a primary strategy in engaging with young populations. For example, Zelenko et al. applied participatory design as a strategy to engage young people in the design and development of technology-based tools for health and wellbeing (Zelenko 2014), while other projects use the approach for online youth counseling (Lund-mark, 2016), guiding ethical decisions (Malinverni & Pares, 2017), and digital youth safety (Colin and Swist, 2016).

3. Framing the problem

A relevant issue currently affecting college students’ development is linked to stress and indecision about majors and career paths. Changing and undecided majors are a persistent trend in universities in United States. About 50-75 percent of college students in the country end up changing their major at least once (Gordon et al., 2000). The stress is increased by financial burden, since being indecisive or changing majors will likely delay graduation and generate more tuition fees for students. Since career decisions are based in identity development, self-reflection, agency, and sense of purpose, many incoming students may not be ready to commit yet. Supporting developmental outcomes in this stage is key to help students to successful explore and choose their career path. Building a future trajectory requires agency and identity work to negotiate transitions in the current scenario (Schwartz et al., 2005).

Career exploration involves activities such as gathering information, talking with others, and self-exploration. Career exploration has shown stability over time (Kracke, 2002), but characteristics of the environment alter the exploration process. For example, experiencing open communication and support for one’s individuality have been linked to improvements in career exploration over time (Kracke, 2002).

Besides environmental contexts, personal characteristics carry implications for career exploration. As shown in longitudinal research, positive changes in confidence relate to improvements in career exploration over time (Creed, Patton, & Prideaux, 2006). The findings suggest the importance of providing situational contexts and promoting individual qualities to enhance the potential for career explorations.

This study proposes applying Participatory Design facilitation to processes of career exploration, providing both space for open communication, and support for individuality. The strategy comprises: (a) at first, interventions for helping students to understand and guide themselves through the process; (b) subsequently, settings for students to co-design career exploration tools for their younger peers (college freshmen or highschool students).

4. Method

The goal of the research is to investigate the application of participatory design theory and methods to support development in the transition to adulthood, focusing on college students in the process of career exploration.

The research is being developed within an internship program at a comprehensive land-grant research university in the United States (Mouchrek, 2019). The internship program engages undergraduate students in diverse fields of knowledge in 12 week summer internships. Beyond working as interns in a variety of industries, students also participate in a semester-long preparatory course, participate in field trips, seminars, and mentoring by faculty and industry partners. Building community is an important goal for the program: both among peer students living together during the internship period and among students in different cohorts. The program has a strong focus on experiential learning, innovation and entrepreneurship. The preparation coursework includes communication skills, team building, leadership, collaboration, creativity, and readiness for the workplace, among other aspects.

The internship program focuses on three main elements: coursework, career, and community. The application of participatory design research in this study is linked to the community element, based on the proposition that students can learn and share experiences among themselves and explore the richness of developmental and creative possibilities through peer network exchanges. Also, since engaging in reflective practices is a fundamental aspect of experiential learning, the program lends itself very well to the application of participatory design workshops aimed at supporting development in the transition to adulthood.

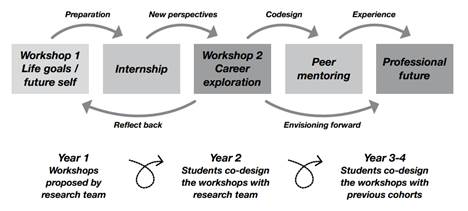

We proposed a series of participatory design workshops to take place periodically within the university internship program (See Figure 1). The workshops aim to utilize techniques including tools for telling and enacting (Brandt et al., 2012) such as: visual maps, affinity diagramming, future personas, card games, group discussions, among others.

In year 1, we hosted two participatory workshops with the first student cohort. The first workshop took place just before the students began their summer internships. The goal of this workshop was to promote reflection and conversation about relevant aspects of students’ developmental phases (life goals, markers of adulthood, and future orientation), in order to prepare them for a critical observation of themselves and their life situations during the internship experience. The second workshop took place three months after their internships finished. We invited students to reflect back on the first workshop, share their internship experiences, and envision their way forward, investigating the process of career exploration and future trajectory building.

In year 2, those students will work together with the research team as co-designers in the workshops, aiming to support the next cohort and strengthening the peer mentoring network. Every year, we will have a new iteration of workshops 1 and 2, aggregating the experiences and perspectives of students of previous cohorts to the initial themes for collaborative reflection and co-creation. After the second workshop, peer networking between the cohorts will be set in motion, with ideation sessions to develop the approach for the next year. In years 3 and 4, the students will be in charge of the workshops by themselves, with two or three cohorts working in partnership to co-design the workshops for the new students.

Workshop 1 - Life Goals and Future Self

The first workshop was held in the beginning of Summer of Year 1 (See Figure 2). Eleven students from a variety of majors participated. The workshop focused on the first stage in the process of career exploration: reflecting creatively about life goals and desired future trajectories. The activities included discussions about challenges in the transition to adulthood, agency and self-authorship as important for defining a life pathway, and choices for the future. Students created a visual map with future profiles of themselves (five years from now), envisioning their life regarding work, school, relationships, family, housing, hobbies, values and lifestyle. Finally, participants collaborated in creating affinity diagrams about the steps they could take (or are already taking) in the present to help build the future life they envisioned.

Workshop 2 - Career exploration and Self-Construction

The second workshop took place three months after the internship, in the Fall of Year 1 (See Figure 3). Eight students attended the workshop, which focused on the process of reflection and intentional career exploration, advancing the work of the first workshop. The follow-up workshop proposed a structured reflection about the results from the first workshop, in light of their internship experiences. Using visual representations and group discussions, students shared what they learned in the summer, how this experience relates to their career exploration process and reflected in their life goals. Participants engaged in a card game, followed by ideation sessions about global challenges they would like to contribute to solve in their professional careers. Each group created and presented one idea for a project in a chosen field, applying each member’s specific talents and background. At the end, students filled a questionnaire evaluating the participatory workshop and investigating their willingness to participate in future workshops in partnership with new students in the program.

Data gathering and analysis

The data was collected through the materials produced during both workshops (visual maps, set of sticky notes, diagrams), the researcher’s notes, and photos. The qualitative analysis was developed using thematic content analysis, generating themes from the participants’ responses. The themes were grouped into categories and mapped according to their frequency. The results were also mapped using visual diagrams. Findings and analysis are presented in the next section.

5. Results and discussion

Findings in Workshop 1

Future Self

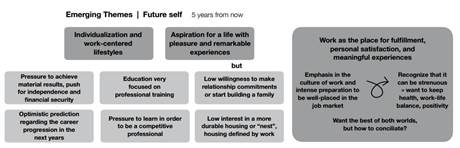

The “future self” activity resulted in general themes for each area. Students were asked to envision their life 5 years from now, and draw a future profile of themselves, regarding 6 areas of life: work, education, relationships, housing, family and values/lifestyles.

Regarding work, the most prominent themes showed the preference for a professional activity that they love and enjoy; and a vision of themselves as established in their careers (either with a high position, running a side business or a fulltime start-up company). Secondary themes were linked to work situations that allow for continuous learning; preference for a job that includes travel experiences and contacting people from different countries. Additional themes approached opportunities to work more interactively with people; work that allows for financial independence; and concern with financial security. The responses show that work is imagined as the place for fulfillment and personal satisfaction, providing meaningful experiences such as enjoyable activities, travel, learning, interpersonal interactions. On the other hand, there is also a more pragmatic orientation, including pressure to achieve relatively rapid material results. Independence and financial security clearly emerged as relevant aspects to achieve.

We observe a somewhat optimistic prediction regarding the career progression, since in just 5 years they would already be in high positions and established careers. Aspects treated in the literature as extreme individualization in the development process, pressure to “win”, and work-centered lifestyles, but also aspiration to a life with pleasure and meaningful experiences are observed. There may be difficulties in reconciling the two guidelines in the future.

Concerning education, the most frequent response indicated an intention to continue education in graduate school, with comments about the value of education and their “love for learning”. The secondary theme indicated a diverse orientation: by that time in the future, they would like to be finished with formal education (“done with school”). An additional theme indicated interest to continue to learn, but in the professional settings, instead of educational settings.

In general, the view of education seems to be very focused on professional training, even those who indicated that they had a “passion for learning” did not report on more holistic outcomes from education. Learning is pictured as a sequence of steps to be taken to compose a profile of a complete professional, desired by the market and therefore with more “power” to develop. In the students’ discourse, a pressure is clearly felt: there is a lot for them to know and learn to be a professional, therefore they need to be proactive, to take advantage of opportunities, etc.

Concerning relationships, a significant number of responses addressed friendships, indicating the importance of keeping a good number of close friends, including people from different life phases (“mix of friends from high-school, college and work”). Another present theme was about romantic relationships: the majority of participants want to have a stable relationship, but clearly not a serious commitment by then (“in a couple, but not married”). “Married” was the response from a very small group of people. The importance of experiencing mutual relationships, either with friends or romantic partners, was also mentioned. In relation to family, there was a single general theme, with participants stating that they would like to keep a close relationship with their family, with frequent visitation (“monthly”). It was interesting to realize that the participants overwhelmingly addressed family as their family of origin, and did not envision constituting their own families by then.

Regarding relationship commitments, participants are not so willing to take on adult roles, compared to work-related issues, for example. Although friendship and mutual relationships emerge as important factors, there is very little willingness to start building a relationship or a family, as the preference is to maintain a more “relaxed” lifestyle. Once again, it is observed that work remains as the greatest source of commitment, realization and personal investment.

Regarding housing, some themes emerged, with no particular tendency. Participants cited housing arrangements such as: living with roommates, living with partner, living in a house with a dog. Two housing characteristics were highlighted by participants: they would like to have: (a) a minimalistic style of living in their houses, and (b) a housing arrangement that allows for little to no commute to work.

In line with the findings in the previous category, participants do not project energy and resource investments into more durable housing, or even the idea of building a space for accomplishments to private life and personal interests. Building a “nest” would be a goal for later in life. Housing arrangements are somewhat related to work, as they are defined in terms of distance and time of movement from the workplace and predict that the person will spend little time at home, in fact.

Finally, in relation to values/lifestyle, one theme was pervasive: importance of staying healthy and having worklife balance (“not to become a workaholic”). Positivity in life was a frequent theme as well, indicated by responses such as happiness and enjoying life. A secondary theme indicated the willingness to have a “highimpact” life, following ideas such as “work hard, play hard”, indicating an intense dedication to both work and fun.

Shaping our future now

When asked what they are doing in the present to accomplish and build the future self they envisioned, participants identified actions that they already undertake as far as desirable actions they want to set out to do from now on. The steps identified were, in order of frequency:

-- Looking for self-guided, informal learning and research (work skills, idioms, career preparation),

-- Cultivating healthy habits of self-care, exercise, and sleep

-- Networking and social integration, including talking to and getting to know people, and keeping in touch with existing contacts

-- Investing in acquiring additional training during undergraduate education

-- Intentionally search for purposeful trajectories, to organize and give meaning to the activities they are undertaking.

-- Looking for graduate programs and companies, exploring different areas and professional fields

-- Creating a Plan B concerning professional trajectory, ideally simultaneously having a clear path and keeping options. Learning more about finances

-- Sharing goals with family of origin, increasing communication for ensuring support.

This activity clearly showed the pressure to which the participants are subjected, possibly for internal and external reasons. Asked about what they wanted to do to prepare for the future, the participants answered what they think they should be doing. It was necessary to reorient the activity in order to bring more lightness to the process, since it was generating stress and a diffuse sense of guilt in the participants. It was evident the importance of giving young people spaces to express these feelings and thoughts, but also provide guidance in strengthening agency and awareness to recognize these pressures and decide how they want to deal with conflicting issues more deliberately, and reflect on personal choices not easily recognized in the face of external demands.

Emerging Themes in Workshop 1

The emerging themes are summarized in Figure 4. Here we see an interesting trend. While participants have stated their orientation to emphasize the culture of work and intense preparation to be well-placed in the labor market, they also recognize that these efforts can be quite strenuous.

Therefore, at the same time, they also want to avoid the “nightmare” of adulthood as a sequence of stress and overtime. Therefore, the importance of maintaining health, balance between work and personal life, positivity. In their own words, they show that they want everything, the best of both worlds, at the same time. It seems a big effort to undertake, especially all by yourself, since the vision is quite individualistic, with not much in terms of being a part of a community - except for having friends, although it emerged more as company for fun activities then a true support system in which people fulfill important roles in sustaining a community.

We observed that, in general, the themes in the workshop were very individualistic and centered on work. Although the activities were broadly oriented to life goals, the future self profiles it ended by being all about work and lifestyles linked around work.

Recognizing the importance of combining individual trajectories with a sense of purpose that goes beyond the individual and allows for a more comprehensive and coordinated way of life with the surrounding community, the second workshop changed the focus a little. The approach was more intentional in promoting sense of purpose by integrating more holistic aspects of life that go beyond work.

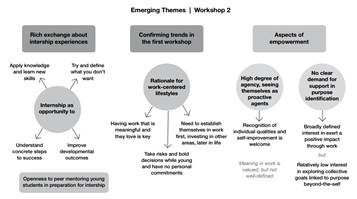

Findings in Workshop 2

Internship Experiences

When asked to share their internship experiences, students engaged in a rich exchange of ideas. Stories about job tasks, climate in the workplace, the upsides and downsides of the job, and the overall experience were shared. Three main themes emerged: (a) opportunity to develop specific work technical skills, organization, and persistence, but above all, to learn about how to relate to people, networking and managing up; (b) opportunity to apply knowledge and skills they already had; (c) opportunity to refine their career orientation by recognizing what do not correspond to their work aspirations.

The work experience has provided opportunity for several developmental outcomes such as clarity of focus, self-direction, self-organizing and planning, productive use of time, self-understanding about wants and needs, resilience and proactivity to improve situations. An interesting comment mentioned learning on how to “actively transform the internship in something meaningful”. The concrete experiences were valuable for them to recognize what they do not like and what they do not want for their work trajectory in the future. Some participants did not like the sector they were working, other did not like the size/type of company, and finally some recognized that the specific job tasks or work structure were not what they are looking for.

It was quite evident in the stories that during the work experience the students critically observed how coworkers, but above all, how leaders in the companies behaved in relation to the work, their vision of the company and how they engaged others in their vision. The group seems to have a specific interest in learning about leadership - many have stated that they intend to be their own bosses, have their companies, and hold leadership positions. Sharing the stories about their work experience in the summer and their reflections about what they learned was a high point during the workshop. Participants offered feedback to others, discussed specific themes and started to create a collective thinking about it. They recognized this strategy as highly beneficial, and agreed that it could be expanded in order to include peer mentoring younger students in the program in their preparation for the internships.

Reflecting back about the first workshop

When presented to the findings of the first workshop, and asked if their internship/work experience had changed their vision in any of those aspects, the students confirmed that their values and goals remain basically the same. They reported that the work experience gave them opportunity to better understand the path to achieve those goals, more concrete steps, ways and “means to achieve success”. Few exceptions included one student talking about plans to start a family and having a house in 5 years and one student questioning the possibility to have a job she will absolutely love, therefore starting to question the idea of full dedication to work.

By the way, the theme “having a meaningful job that I love” was strongly recurring once again, appearing to be a key motto for the participants. However, the concept is still not clearly defined. In general, this is associated with the pleasure of doing the work itself, interactions in the workplace, but mainly with a sense of purpose associated with “passion for the company’s vision”. “Having a positive impact on others’ lives” has also been briefly mentioned but not expanded. Working in something they do not love is identified as “tough”, and “monotonous”.

When showed the analysis of the previous workshop showing extreme individualization and work-centered lifestyles, having work as the primary place for fulfillment and personal satisfaction, participants in general do not agree that this would be a problem or concern. They justified and reinforced this choice of focus. One strong justification was the idea that they need to take risks and bold decisions about their career early, while they are still very young. Thus, when they are older, they would already have established careers and could form relationships and family, without subjecting others to the consequences of their taking risks.

It is not that they do not value achievement in other fields of life, but this realization is postponed, it belongs to a later stage of life, when the issues about professional accomplishment will be already solved. For now, students appear to be completely work/success-oriented, with success emerging as an almost unquestionable value. Also, all the efforts seem to be justified by the other imperative: work should equal love and fulfillment.

Activities: Superpowers & Global Challenges

The exercise about identifying their “superpower” in work groups was welcome by students, while the exercise about “world challenges you want to tackle” did not have the same traction. As this group is already relatively advanced in the process of career exploration, there is no clear demand for support in purpose identification, while everything that seems to add in the recognition of their individual qualities and in what they must improve seems to have more interest and attraction.

The main talents they recognize in themselves are empathy, leading/decision setting, and motivating others. The main global goals they selected were quality education, reduce inequalities, and decent work and economic growth. With few exceptions, the interest to consider in depth the goals as a purpose beyond-the-self was low. The exception came from people who aspires to help others in similar situations to theirs, family, close and extended community.

When asked if they see themselves fulfilled by working towards one of the global challenges goals, some said yes and reiterated their purpose, some said that they saw themselves performing a similar type of work, but for other purposes, and others linked purpose more to the major they chose or to the individual work trajectory then envisioned than to a call to work for results beyond the self.

Possibly, it reflects the fact that their general training and career orientation environment values relatively less the sense of purpose beyond-the-self, in relation to other more individualistic aspects. This can be explained by the level of demand and challenge of the labor market, coupled with the imperative of having money and social position to “be someone”, and the fact that students in this generation have to build their trajectory totally from themselves, since the system has few community support structures.

We had a different result in a pilot application of the same activity with a cohort of incoming freshmen students in engineering in the same university, a couple weeks before the workshop. Those students were much more interested in thinking about the collective goals as a way to help guide themselves through career exploration. A possible explanation is that students in early career exploration process would be more open and interested in this approach as it provides a general orientation to their search, while students in further stages are more geared towards their actual path to the job market and less concerned with big picture goals at that stage.

Emerging Themes in Workshop 2

Workshop 2 was an opportunity for rich exchange about students’ internship experiences. In general, the trends identified in Workshop 1 were confirmed, with participants offering more elaborated rationales for their choice for work-centered lifestyles. Regarding aspects of empowerment, participants showed a high degree of personal agency, increasingly seeing themselves as actively building their work trajectory. We conclude that, for these students, recognition of individual qualities and self-improvement are welcome; and that meaning in work is valued, however ill defined. However, it was not possible to identify a clear demand for support in terms of deeper exploration of purpose in life. Participants show a broadly defined interest in exert a positive impact through work, but a relatively low interest in exploring in depth purpose-driven collective goals.

Our attempt to frame the second workshop towards the importance of considering life as a whole and recognizing possible inner postures in dissonance with the outward orientation towards a fully work-oriented life was not very successful, with few exceptions. The orientation towards community aspects was relatively low, compared to individual focus on building a professional trajectory for themselves. It was interesting to see these dissonant voices in the group. One who does not identify with the long hours of work and does not believe that satisfaction will come all of the work, another that has a clear purpose of raising others around her. Even in these cases, the orientation to success was strong, but with a different flavor on how to achieve it and what success could mean for them. The emerging themes in Workshop 2 are summarized in Figure 5.

Meta reflection about the participatory design process

Participants stated that the participatory design workshops did very well in providing an effective structure for participation, in offering possibility to learn from peers, and in providing opportunity to reflect about life and career choice. On the other hand, the workshop did only moderately well in creating a dynamic and energetic environment and in strengthening the sense of community in the internship program. Comments reinforced that participants like the relatively unstructured flow of the workshop, which gave them opportunity and freedom to express their perspective and reflect within the group. They learn a lot about their peers and with the others’ experiences as well. Although they appreciated the time for reflection, some participants would prefer a more energetic approach. 75% of participants would like to participate in a future workshop working in partnership with new students in the internship program.

6. Final considerations

The experience with the workshops showed the potential of participatory design facilitation to open a space for dialogue and collaborative career exploration for college students,uncover underlying issues, and better understand the context of career exploration for college students. The design-based structure for participation was considered beneficial, constituting a kind of guided but openended reflection allowing free expression and creativity. It is important to consider the particularity of the group, as they were relatively advanced in the process of career exploration, as many are business-oriented and interested in leadership. The following years in the research will take advantage of their interest in constituting the community around the internship program and promoting the workshops based on peer mentoring, offering structure to the experiences and expertise that they are constituting as a reference for younger students, positioned earlier in the process of career exploration.

The workshops were also supporting development at the extent that the students project future possibilities and enact choices, while reflecting both individually and collectively. Presenting your own ideas and experiences, while hearing other people’s stories and viewpoints, and working together to design ideas for projects with common goals allowed participants to expose and put in perspective many assumptions. For some students, it reinforced their choices, for others it enriched their understanding, while for some the collective reflection will likely support pivoting their career orientation while they mature the process.

The results and emerging themes will allow to develop further investigation about individualistic work centered lifestyles, purpose and meaning in work and life, and design interventions regarding career decision-making in the transition to adulthood.