Introduction: poetry, or the art of seeing images

Comic books and their more mainstream concept of graphic novels have crystalized humans’ attempt to combine the two main communication modes -the written word and the image-, a fusion that met massive acclaim and readership during the first decades of the twentieth century in the Western world. Thus these comic prose narratives became increasingly influential in Europe with the arrival of the French comic periodical Les aventures de Tintin starting from the late 1930s, and in America almost a decade later in the form of the superhero comics. Linda Hutcheon (2013) recalls the words by the Canadian artist Cameron Stuart who claimed that comic books (mainly those about superheroes) were made with Hollywood in mind, which heightened their male protagonists as modern Redeeming Fathers of humanity. As the previous instances of comic books prove, this form of art has been long dominated on the one hand by male-centered stories and, on the other hand, by a preference of the narrative form of language in prose. Since the focus back then was not so much on the language but on the message-with socio-political overtones, as Tintin’s adventures show, for instance-, adaptations of previous works of literature did not interest the public.

However, nowadays the scholarly eye is turning toward the study of the adaptations into comic form of some of celebrated works of literature aiming to shed light on modern readings of existing stories, including narrative poetry. Hence, the study of the systems of signs in the new revisions in rapport with the original works draw on semiotics to disentangle the multimodal meaning of a work of literature. As this article shall explore, the use of visual mechanism such as framing and graphic representations of time are the visual equivalents to the linguistic segments that divide a poem and endow it with the quality of narrativity. The American poet and scholar Rachel Blau DuPlessis has suggested the term “segmentivity” for the traditional divisions of a poem:

“Segmentivity” constitutionally distinguishes the poem. This means poems are formed by their uses of segments -gaps at the turn of every line break; segments counted as/created by regular rhythm; caesura or the intralinear use of page space; gaps between stanzas; leaps and gaps in the grammatical ordering; interesting clashes when sentences (one kind of segment) articulate across lines (another kind of segment) (2012, p. 61).

The semioses at stake in the adaptation of a piece of literature from one medium (e.g., written word) to another (e.g., graphic adaptations in the form of comics) have been the focus of intermedial semiotics and social semiotics for decades. This process of meaning-making from one medium to another has received different names such as: “transduction” (Kress, 2005, p. 36) or, more recently, “transmodal operation” (Wyatt-Smith and Kimber, 2009, pp. 77-78) and “transmodal moments” (Newfield, 2013, p. 103). Hutcheon has affirmed in her study: A theory of adaptation that, “an adaptation is an announced and extensive transposition of a particular work or works. This ‘transcoding’ can involve a shift of medium (a poem to a film) or genre (an epic to a novel)” (2013, p. 7). This scholar further notes that the sign system must be changed in order to adapt the new version to the affordances and demands of the target medium:

In many cases, because adaptations are to a different medium, they are remediations, that is, specifically translations in the form of intersemiotic transpositions from one sign system (for example, words) to another (for example, images). This is translation but in a very specific sense: as transmutation or transcoding, that is, as necessarily recoding into a new set of conventions as well as signs (Hutcheon, 2013, p. 16).

Although agreement has not been reached on a suitable definition of what comics are (some artist prefer to call them “graphic novels” or “sequential art”)2, the ergodic role that readers must now assume in order to bridge the cognitive gaps designed by the artist remains undeniable (Earle, 2017, pp. 149-150). It is worth noting that the concept studied in this essay refers to poetry adapted into comic form and it should not be confused with the new concept of “comics poetry”: “[c]omics poetry isn’t poetry as text with comics images; it’s the whole comic as poetry. The images, the words, the structure, the rhythm, the page, all of it is used together to create the poetry, to create comics in a poetic register” (Bennett, 2014, n/p).

For the semiotic study of female representations in John Keats’ poem “La belle dame sans merci” and Edna St. Vincent Millay’s poem “The singing-woman from the wood’s edge” this research draws on three major works of intermedial analysis. First, the American cartoonist Will Eisner’s pioneering masterpiece: Comics and sequential art from 1985. In it, Eisner emphasizes the ergodicity of comics as “[t]he format of the comic book presents a montage of both word and image, and the reader is thus required to exercise both visual and verbal interpretive skills” (1985, p. 8). Eisner devotes special attention to the question of focus when drawing a series of panels, an aspect of the visual language that will serve us to examine the identity of the female protagonists of the two poems that we compare in this essay. Based on Eisner’s book, Scott McCloud published in 1993 his well-known Understanding comics: the invisible art in which this comics theorist and cartoonist aims at legitimizing comics as a form of artistic expression.

On chapter six of his book entitled “Show and tell,” McCloud denounces the long-held distinction between high art and low art and fears what an uneducated vision of comics may bring to this craft: “words and pictures together are considered, at best, a diversion for the masses, at worst, a product of crass commercialism” (1994, p. 140). Of particular interest are his words about the conceptualization of time and its embodiment in the form of drawn spaces, as the following pages explore. Finally, the British semiotician Gunther Kress and the Dutch linguist Theo van Leeuwen published in the year 1996 their famous book: Reading Images: The grammar of visual design which meant a magnificent momentum in the field of semiotic multimodal communication studies. Although they mainly analyzed banner adverts on paper, they are credited with being among the first scholars to provide a deeply semiotic explanation for the cognitive mechanisms of coding and decoding multimodal language.

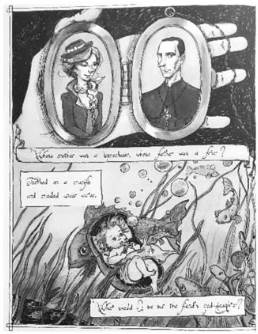

Based on the previous studies, the following pages develop a semiotic reading of the Romantic poem “La belle dame sans merci” (1819) by John Keats and “The singing-woman from the wood’s edge ” (1920) by the American poet Edna St. Vincent Millay and two contemporary adaptations to the comic form which shed modern light on the view of women. But, what joins these two poems separated from each other one century in time? In her study: “Andromeda Unbound: Gender and Genre in Millay’s Sonnets” Debra Fried has noted an influence of Keats in this Millay in relation to the her poetic style (1986, p. 2) beside the noticeable influence of the Classics in both poets. But despite the artistic backdrop in which she produced her works, some critics find in Millay an author for whom Modernism passed unnoticed and who went back to the conventions that marked the Romantics instead (Montefiore, 1987, p. 115), which is immediately noticeable in the lyric style in “The singing-woman from the wood’s edge.” Keats’ ballad “La belle dame sans merci” is a narrative poem in which an unnamed narrator warns a “knight-at-arms” (l. 1) about the doomed fate of all knight that have fallen prey of this “faery’s child” (l. 14). At no point in this poem do we hear the voice of this femme fatale, and we totally ignore her motivation or aim in her proceeding. In Millay’s poem: “The singing-woman from the wood’s edge” we hear the protagonist’s voice wondering “What should I be (…)?” (ll. 1, 18, 36) with slight variations of this question throughout the poem. This sonnet is half autobiographical in view of the details she gives such as the fact the woman in the poem- described as: “the fiend’s god-daughter” (l. 4)- saw her parents separate just like Millay witnessed the traumatic divorce of her parents when she was only eight (Cotsell, 2005), an event that is also traumatically depicted in the comic adaptation. The following sections analyze the visual aspect in each poem paying special attention to the visual rendering of women in each of them.

Keats’ belle dame revisited by sequential art

In his enigmatic ballad “La belle dame sans merci,” John Keats presents an uncanny atmosphere in which the only character who seems to be in her home is the murderous lady, compared y some critics with Keats’ unattainable lover Fanny Brawne (Kelley, 2007, p. 70). The lady in this ballad is presented as a fallen woman, a temptress (Alwes, 1993; Twitchell, 1975). The narrator’s perspective changes, being the first four stanzas spoken by the ‘belle dame’ and the rest of the poem being voiced by her victim. The knight is abandoned by the lady “alone and palely loitering” (l. 42) at the end of the poem among images of a decaying landscape that foreshadow his imminent death. One of the metafunctions analyzed by Kress and van Leeuwen in their book is the interactive one, which contains the eye contact that viewers establish with the images (i.e., gaze) and the social distance.

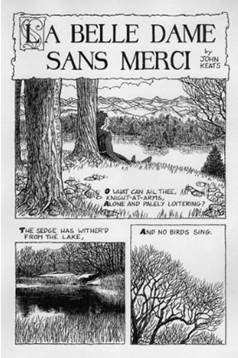

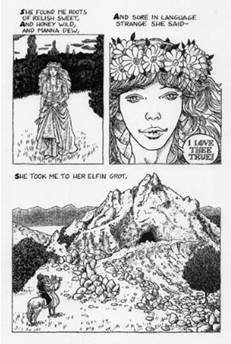

Julian Peters’ graphic adaptation of Keats’ ballad lacks panels in which the character’s gaze is directed towards the viewer, which implies an intimate atmosphere as if the reader were an outer observer of the evil curse that the man is about to suffer. There is, however, a panel which states that: “her eyes were wild” in which the semiotic mechanism of gaze is emphasized in the iterative pairs of eyes as the panel on the bottom right of Figure 1 shows. The observer feels the mesmerizing effect of this woman-witch by means of her eyes, seductive and hypnotic as they are when they “thee hath in thrall!’” (l. 40). Gaze works in a way than ensures the active involvement of the observer in the meaning-making process (Kress and van Leeuwen, 1996) in the comic. This engagement draws on the readers’ imagination in the case of narrative literature (Hutcheon, 2013) while in the visual mode, it is based on other semiotic mechanism of perception. The size of the frames in each panel also informs about the level of proximity with the knight and his mistress. Interestingly, most close-ups show the man (see Figure 2) and the medium-shots are more often used to represent this evil fairy (see Figure 3). This distance of the woman with the readers/observers of the poem makes sense if we consider the fact that, as mentioned before, only the initial four stanzas show the woman’s perspective since the male vision dominates the poem. It implies that the larger the distance with this wicked fairy, the lower the observers’ empathy with her (Kress and van Leeuwen, 1996) as the size of the frames and panels is not as large as those of her lover-prey. Peters’ comic paradoxically makes visible the silenced voice of the woman in Keats’ poem via visual representations3.

The three principles of composition of multimodal texts (such as comics) are: salience, framing and information value (Kress and van Leeuwen, 1996). Salience refers to the parts of the image that are first perceived and it is the outcome of: “size, sharpness of focus, tonal contrast (…), color contrasts (…), placement in the visual field (…), perspective (…), and also quite specific cultural factors, such as the appearance of a human figure or a potent cultural symbol” (Kress and van Leeuwen, 1996, p. 202). The relative size of the images is a mechanism that calls the viewers’ attention to a specific image or part of a panel (Kress and van Leeuwen, 1996). In Peters’ adaptation of the Romantic ballad, every time the lady is presented we are made aware of her physical attributes, which stress her danger according to the stereotype of the voluptuous woman-temptress. The lady’s “hair was long (…)” (l. 15), appealing and sensuous, one of the most representative features of the femme fatale. As we shall see in Millay too, the woman in the poem is closely related to natural imagery. As Figure 3 shows, her garland is a visual highlighter that stresses the captivating nature of this “lady in the meads” (l. 13), she is also surrounded by flowers and animals that represent beauty and the ephemerality of life, such as the butterfly (see the upper panel in Figure 1). Yet, we are informed that Psyche’s iconography -the soul- in Ancient Greece was associated with the butterfly as the word “psyche” means in Greek both “soul” and “butterfly” owl, symbolizing death (Keats, 2001, p. 552). Eros and Thanatos are indissolubly blended in “La belle dame sans merci” and the graphic version stresses the salience of these symbols. Some critics have found in this female vampire the loss of the maternal in Keats (Alwes, 1993) and, moreover, the loss of salvation and the certainty of the man’s death in entering into her deathly realm.

The information value of the human figures on the upper panel in Figure 4 shows the perspective of the woman (corresponding to the female speaking voice at the beginning of the ballad). In that panel, the man is presented leaning against a tree in a wood’s edge who is “[a]lone and palely loitering” (l. 2) (there is in this scene an undeniable similarity with the setting in Millay’s initial panel). The man is placed in the center of the panel, which gives him full attention (Kress and van Leeuwen, 1996) and sets the lady as a dangerously bewitching temptress for whom the knight is a prey. Yet, as the story advances, the comic shows the woman in the right margin of the panels (see Figure 3), a side of the image in which the new information is depicted (Kress and van Leeuwen, 1996). The lady represents a deadly promise of eternal happiness, which he still ignores and which turns out to be the final damnation of his soul as it had been for all the “pale kings and princes (…), / Pale warriors (…)” (ll. 37-38).

The framing mechanism in Peters’ adaptation is very illuminating about more possible readings of the poem. Almost all the panels are framed. Since the lack of framing stands for group identity (Kress and van Leeuwen, 1996) it is then understandable Peters’ decision to frame most panels, since Keats’ aim is not to speak of human experiences in general, but, in line with Romantic tenets, to verbalize his own feelings and emotions. The discontinuity between the panels is achieved with gutters separating them as they narrate a story which should not be taken as a universal one, but as an intimate experience depicted poetically. The comic only shows a few instances in which the panels are not framed, creating a sense of limitlessness for the characters drawn in them, of transcendence from their space and time. Interestingly enough, this visual openness is only granted to the dame (see the lower right panel in Fig. 1, the second and third panels in Figure 3, and the lower panel in Figure 5). The images confirm the ballad’s mood: the lady does not belong in this world, either because she is a spirit or because she is out of the narrator’s reach. This poem marks the beginning of a deadly aftermath for the naïve knight. He succumbs to her charms as the framed panels show the woman in the form of a higher creature (she has transcended the immanent) whereas he is tied to the mundane world, albeit temporarily. This aligns with Keats’ desire to transgress time and transcend mortal life to attain immortality through his poetry and freeze a specific moment in time to endow it with eternal life (Keats, 2001, p. vii).

The frames in the panels help observers to understand the hidden layers of meaning of an adapted work of art. As such, the graphic illustrator is the first medium of interpretation or mediator of the work of art prior to its transformation into a multimodal artifact. As examined before, the action narrated by Keats aims at attaining immortality via very vivid language and visual metaphors of flowers to represent death (as can be read in the third stanza of this ballad), ghosts and ethereal images. The narrative value of this poem lies in the continuity of the event narrated in a non-linear manner: the poem begins with the encounter of the youth and the knight and from there, he narrates the story of his fatal ending in the form of a fairy tale. Hence, the central part of the poem is an analepsis of his tragic fall. The last stanza of the poem returns to the present tense, to a sort of atemporal, deferred present time. Scott McCloud explores in the fourth chapter of his book how framing expresses time. McCloud (1994) also states that we perceive images as a fixed, single instant in time so that the frames help us to encapsulate each action in a sequence of events. The temporal dynamics in this comic is met mainly with the linguistic code so that the voice of the narrator (caption) is often not framed and it serves as the linking vector that endows the panels with temporal continuity (see Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4). In general, in spite of being a narrative poem and, thus, relying on the temporal axis more than other types of poetry, “La belle dame sans merci” presents moments frozen in time or in an eternal present time. This is illustrated in Peters’ version with the delimited panels and the lack of vectors or lines of movement. Keats’ poem is non-linear and the comic shows this fragmentation in the form of visibly separated panels with large gutters and loose captions between them thus producing a sequence of frozen moments (McCloud, 1994). There is also a sense of circularity in the poem: the first and last stanzas emphasize the blocking of the time flow. The “splash pages” (introductory pages) of the comic show this circularity (note the similarity of these panels and Kolitsky’s adaptation of Millay) presenting the knight (in Keats) and the girl (in Millay) in the wood’s edge in both comics, implying their sense of unbelonging and spiritual loss. Although not mentioned in the ballad, the mistress also lived in a sort of threshold between death and life, and across time (present, past and future). In reality, the narrativity that exists in this ballad (just like in Millay’s sonnet) and which is made evident in the comic form, too derives directly from our individual perception of the events in the story, which are mediated by the author’s use of the visual and verbal devices thus reinforcing our view of the poems as more or less circular, non-linear, fragmentary, etc. According to the poet and scholar Jan Baetens: “[n]arrative is not something that defines or characterizes a whole work, but something that affects the perception of certain elements in that work in ways that are never final or definitive but always open to contextual renegotiation” (2011, p. 106).

In his poem, Keats plays with time blending the past and the present into a sort of universal, frozen present that exists and escapes the narrator simultaneously. Accordingly, the drawing of the frames of the panels that deal with the encounter with his mistress have rectangular straight lines, instead of the curved edges typically employed to depict past time (McCloud, 1994). But the frames also raise the viewers’ emotions towards the comic, serving as a psychological semiotic device (McCloud, 1994). Thus, readers have a sense of oppression when faced with the natural landscape in the first panel of the comic version (Figure 4) as it is framed and shows the man’s impossibility to escape his fate. Contrary to this vision of nature, when the landscape is presented as the home of this evil lady, it is open, evoking freedom in viewers, transcendence from this world. The use of perspective in comics is another mechanism that calls upon readers’ emotions and equates the poet’s own point of view in narrating the miserable ending of his knight in the hands of a wicked woman. The comic shows in some panels both the man and the woman when the knight’s voice is narrating his sad deeds. Figures 1 and 3 are the most striking cases of an outer observer’s view intruding in the knight’s mind and the maiden’s fairy land involving readers and observers.

The voice of the two characters is powerfully controlled by the narrator’s own perspective. In Peters’ comic there are not many speech bubbles and instead, loose captions are used, to symbolize the reigning voice of the narrator at the expense of the knight’s or the lady’s. But, in fact, it is the maiden’s perspective that is most ‘invisibilized’ in both works (the poem and the comic): the maiden is only given one balloon, when Keats has the gallant remember: “[a]nd sure in language strange she said- / ‘I love thee true’” (ll. 27-28). Regarding the man’s few speech balloons, their font type is the same as the one in the captions for the narrator’s voice, which again accentuates the closeness between the (male) persona in the poem and the knight at arms. Interestingly, the typography that the graphic artist has used in the lady’s balloon is more ornamental, baroque, carrying the emotions of the speech (Eisner, 1985), in this case, a false promise of love as the second panel in Figure 5 reflects. The counterbalance to her ardent speech is the warning uttered by the specters about her murderous charms (first panel in Figure 6). The bordering of the ghosts’ balloon is spiky, symbolizing the danger and risk for the knight if he lets this woman lure him. In all previous cases, the male voices -and their corresponding speech balloons- are stronger and more abundant than the ones allocated to the maiden, a situation that is counteracted with Millay’s poetic response in giving prominence to the female voice in “The singing-woman from the wood’s edge.”

Millay’s woman drawn: visible subjectivity and invisible borders

“The singing-woman from the wood’s edge” is one of Millay’s most light-hearted poems and it narrates in vivid language the story of a first-person narrator since she was born. With noticeable auto-biographical details, Millay originally entitled this poem: “The Changeling-The Hybrid” (Millay, 2016, p. 51). The original title hints more directly at the author’s intention to direct this poem to the world of fantasy governed by fairies and witches who, according to the old tradition, would steal children and play evil tricks on mortals4. Millay did not intend to become the spokesperson of all women. She drew on classical poetic forms such as the ballad (one of Keats’ preferred forms) and Romantic tropes in order to subvert the view of women in traditional poetry and illustrate how literature has deprived them of a voice of their own (Fried, 1986, p. 2-3).

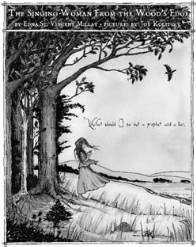

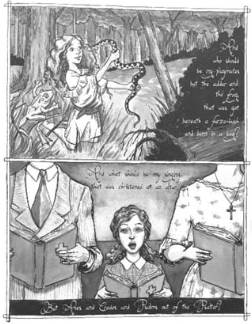

Contrary to what happened in Keats’ poem and in Peters’ adaptation, Millay’s “The singing-woman from the wood’s edge” and Kolitsky’s graphic version both focus largely on the character of the narrator relegating men to a secondary role. The mechanism of eye contact or gaze is barely present in Kolitsky’s version, which contrasts with Millay’s close, personal overall tone in her sonnet. Nevertheless, the panel in the middle in Figure 7 directs the persona’s gaze (who is also the protagonist’s) to the observer, involving viewers in her demand for moral advice when she is faced with the dilemma of being: “yanked both ways by [her] mother and [her] father / With a ‘Which would you better?’ and a ‘Which would you rather?’” (ll. 33-34). Kress and van Leeuwen (1996) claim, in this respect, that a direct gaze at the viewer stands for a demand on the part of the participants on the image. Now the engagement is realized through language and images simultaneously, which stresses the identity problem Millay poses all over her poem. The size of the frames in the panels speaks of a distance with the narrator since the abundance of long-shots and medium-shots reveals Millay’s sense of loss of identity. Long shots are most revealing and they show the narrator either alone or in the company of her mother and father, yet indicating an evident alienation from them. Figure 8 and the last panel in Figure 7 correspond to the first and last lines of the poem and their long-shot-depictions offer an impersonal view of the speaker (Kress and van Leeuwen, 1996), who is lost in her inner world, plunging lonely in her thoughts as she stands on the wood’s edge.

Kolitsky’s comic reinforces the semiotic value of some elements which are not mentioned by Millay (such as the color of her hair). The salience of the red color in the hair of the girl, her dress, and the fire are not hinted in the poem and they add extra interpretative material to Millay’s narrative sonnet as can be observed in Figures 7, 8 and 9. The salience of this color bears biographical tokens since Millay was aware of the history of red-haired women, the fear they inspired in men and their alleged wickedness. Thus she speaks of herself in a self-portrait poem addressed to Edmund Wilson entitled “E. ST. V. M.”: “Hair which she still devoutly trusts is red… / A large mouth, / Lascivious, / Asceticized by blasphemies” (ll. 1-4; Gilbert and Gubar, 1994, p. 73). All the former images highlight a sense of rebelliousness against the norm and, most importantly, Millay’s perception of herself, which is smartly depicted in Kolitsky adaptation. Human figures are also salient elements in the images since they often appear together with fantastical creatures and animals that interact with the girl or with her mother. Thus we read of her “playmates (…), the adder and the frog” (l. 5) and the “webs on the wet grass (…) / [that] a pixie-mother weaves for her baby” (ll. 9-10) in a setting that resembles more a fairytale or an Irish folktale than a poem from the early twentieth century.

The information value of graphic representations tells us that the right margin of a visual representation is devoted to new information and the left hand, to the given one. Similarly, the upper margin represents the ideal whereas the lower margin represents the real (Kress and van Leeuwen, 1996). Kolitsky’s comic is incredibly enlightening about the implicit semioses in Millay’s poem. If we have a look at the beginning and the end of the comic, (Figure 8 and the upper and lower panels of Figure 7), we find that Figure 8 shows the Millay-like protagonist in the center of the panel (maybe a little to the left), whereas in the two panels on Figure 7 she is depicted on the right margin. This can be interpreted not only as a movement in space (in the space framed by the panel) but as an internal movement towards self-discovery, in the direction of finding an answer for her quest of identity given that she is displaced to the right margin-i.e., that which is new.

Concerning the framing of the panels and the images on the page, Kress and van Leeuwen make an interesting remark adding another interpretation to the existence or lack of frames: “[t]he absence of framing stresses group identity, its presence signifies individuality and differentiation” (1996, p. 203) and in this comic there is not any loose image. Every single panel is framed by a double line which hints at Millay’s alienation from a society in which she did not feel identified as a woman, with its strict male-dominated norms and narrow roles for women. However, Millay’s life and works are full of paradoxes (Abril Hernández, 2019) just like in this poem, where a priest is contrasted with a leprechaun (i.e., her father and her mother, respectively, l. 14) and she is at once the “fiend’s god-daughter” (l. 4) and a harlot and a nun (l. 18). The girl and narrator of this poem is depicted in a merry mood when she is surrounded by animals and fantastic creatures as the upper panel in Figure 10 shows. However, the lower panel on the same figure cuts the heads of her mother and her father, implying once again the social distance and feeling of unbelonging she experimented when surrounded by other people, even by her own family. This is only partly true, since Millay lived a life rather distant form her father after her parents’ divorce, she was a loving child to her mother, to whom she owed her passion for literature and poetry (Millay, 2000, p. v). Framing is possibly the most powerful visual device as it encapsulates human experiences and time lapses and condenses them (Eisner 1985) to be expressed in the universal language of images.

The framing of the panels presents visible gutters between them and there is no visual vector or index indicating the direction of reading. It is the linguistic mode which endows this comic with the temporality and narrativity of the story of the protagonist from her birth to adulthood, much like in Peters. As McCloud declares: “in the world of comics, time and space are one and the same” (1994, p. 100) so that the spatial representations represent the passing of time. All the panels in which Millay recalls her childhood life are full of animals and creatures (see Figure 10). This does not only take the observer to a different spatial setting (that of a land of fantasy) but to a different time, a time outside the immanent world to which the narrator seems to be but loosely connected, like the lady in the meads in Keats’ ballad. The passing of time is depicted by Kolitsky in the stages of the narrator’s life since she was “teethed on a crucifix and cradled under water” (l. 3) to her lament: “Oh, the things I haven’t seen and the things I haven’t known, / What with hedges and ditches till after I was grown” (ll. 31-32). In this poem, the past is only partly left behind for her, since it still lurks in her adult life, and the future is still uncertain for her; all she can count on is the present. The present here is made eternal, just like in Keats’ poem and its graphic adaptation. But the visual language of comics allows for a representation of the past, the present and the future all at once (McCloud, 1994), which contrasts with the apparent stasis of the events narrated in the panels.

The converge of the past and the present in this poem in quest for a sort of eternal present is visually manifested in the panels’ straight borders (Eisner, 1985) even in the scenes from her childhood. Millay’s identity is still open, unclosed, in process (Abril Hernández, 2019). It follows that the comic version lengthens the present time by means of the borders of the panels, in the form of straight boxes calling for the present time. Although Millay has not found her identity, her inner ‘I,’ she is still in control of her life and her surrounding, as the drawing of the panels prove. Normally, open panels (panels without frames) are used to represent openness in space, time and location (Eisner, 1985), but this comic has each of its panels well-framed, encapsulated. A semiotic reading of this mechanism from a psychological perspective informs about Millay’s determination and self-awareness of her situation, however desperate it could seem in her quest for her inner voice as a woman. The upper panel in Figure 11 works as a meta-panel for the image of the narrator’s photographs of her parents drawn here as metavisual representations. This metapanel provides interesting information about the life of the author (from a semi-autobiographical reading of this sonnet). In it neither of the parents receives the focus of attention since they are placed in the very center, so that while still as a child, Millay did not favor one of the two, until the divorce. Then, the narrator of the poem claims that her father related to her: “with a prayer for [her] death and a groan for [her] birth” (l. 21) until, finally, she and her mother: “watched him out of sight, and (…) conjured up the devil!” (l. 30). Figure 9 shows the two women undressed, dancing around a fire in the manner of witches invoking the devil. The splash page in this comic occupies the entire page leaving only the upper part for the title of the poem and the names of the poet and the graphic illustrator. This page sets the intimate tone of the poem, which is not universal, but rather a personal experience, as in Keats’ poem. The only human figure in the first page is the narrator/protagonist, who is placed in the threshold of a wood. This is a poem about places in-between, thresholds and internal struggles. The initial picture in Kolitsky’s version depicts perfectly the tone and message of Millay’s sonnet. But if we have a look at the last panel in the comic (lower panel in Figure 7), we come across a curious deed: the woman is no longer standing on the verge of the wood, but she is finally walking away from it, following an invisible track. The first and last panels give a sense of temporal and thematic circularity to this poem, which Millay made explicit in the repetition of certain lines and elements, such as the rhetorical question that prompts the narrator to find her voice. However, in spite of her final anagnorisis this panel is not represented in a large size if we compare it with the one above it, which shows her parents trying to convince her to choose one of them. This may be read as a claim that her identity is never completely definite or closed, since, as she knows, nothing is fixed and she will never come to define herself in absolute terms with closed-up labels. Since identity is not a uniform state but rather a process, a human condition, her finding is ephemeral, only time will bring a new definition for her. This accounts for the fact that, at the end of the poem, Millay chooses not to answer the question and declares instead: “what should I be but just what I am?” (l. 36). This is also the reason why in the comic no path is drawn on the grass, no trail, not even a destination she heads for: because movement in this poem is not visual or linguistic, but internal, toward self-discovery.

Conclusion: drawing female subjectivity between the lines

Millay’s poem is entirely narrated by the woman in the threshold, “in the wood’s edge” as the title reads and her perpetual mantra “what should I be…?” (ll. 1, 4, 18, 36) echoes her internal unrest. However personal, this poem provides a most powerful response to Keats’ ballad by giving a voice to his unheard “belle dame.” Millay stands on the side of the “faery’s child” (l. 14) in his poem and has her woman wonder who she is, passing through all the roles women have been assigned throughout history: harlots, nuns, liars, and witches (“fiend’s god-daughter”, l. 4). In his multimodal reading of this Romantic ballad, Julian Peters is faithful to the representation of the ghostly woman in the poem as a temptress whose words are almost always mediated by the knight and the narrator. Joy Kolitsky, for her part, presents a colorful setting in her adaptation of the sonnet of this poet. This graphic artist combines the private and the public spheres implicit in Millay’s lines with encapsulated panels representing the safety of her mind. Kolitsky opposes them with the openness of the field and nature where the narrator is at peace.

The visual depiction of the two women in both pieces of poetry is accurately transposed in their respective comic adaptations by the two graphic designers and they provide complementary visions of women. Peters draws a temptress who bears all the attributes of the femme fatale in Keats’ poem while Kolitsky shows the young woman in Millay’s own sonnet. The infantine images in the latter comic do not speak of a less strong personality than that of the captivating lady in the former. On the contrary, by presenting a young girl in search of her identity, Millay is vindicating the right of women to choose their own path, as her protagonist eventually does. This is translated in the determination with which the red-haired girl embarks on a trip towards her emancipation once she has found the answer to her dilemma. Finally, both comic versions lack a clear sense of movement in their images, which comes as the most powerful device to avoid drawing an instant of time and to portray an eternal present aimed instead at lasting throughout the centuries.