Stories, as human beings, need to adapt in order to evolve and also, to migrate to other contexts and formats (Hutcheon, 2006, p. 31). Therefore, adaptations always imply change no matter how familiar a narrative seems because the pleasure of experiencing it relies on “the comfort of ritual combined with the piquancy of surprise” (Hutcheon, 2006, p. 4).

To Kill a Mockingbird, a southern gothic story about a lawyer named Atticus Finch who represents an African American wrongly accused of a crime during the Great Depression might sound familiar, whether experienced through Harper Lee’s (1926-2016) Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, the 1962 Robert Mulligan film adaptation starring Gregory Peck, or even, just because we heard about it from a third source.

Scout Finch, the narrator, and her adventures with her older brother Jem trying to meet their reclusive neighbor, Boo Radley, are also well-known and multiply referred to in popular culture -and represented in Broadway. Therefore, it may not come as a surprise that this Bildungsroman has been adapted once more into a graphic novel by the English artist Fred Fordham (b.1985) and published in 2018.

The graphic novel adapts most of Lee’s story in the same chronological order. It starts in the summer of 1933 and goes until 1935, revolving around the residents of Maycomb County, especially the Finch family. On one side, the children Scout and Jem have their own adventures with their new friend Dill trying to trespass the Radley’s property out of their fixation on the urban myths surrounding Boo, and playing at Mrs. Maudie’s lawn. At the same time, their father, Atticus, is appointed to defend Tom Robinson who has been accused of rape to Mayella Ewell. The town disproves because the defendant is an African-American, so while adults try to intimidate Atticus, their children bully Scout. The trial demonstrates that the defendant is innocent -and also that Mr. Ewell drinks and abuses his daughter. Even though, the jury finds Tom guilty. For that reason, he tries to escape from prison and gets shot.

Still, Mr. Ewell seeks to take revenge and one night that the Finch children are walking home at night, he tries to hurt them, but Boo Radley saves them, killing the offender. However, the sheriff decides that the official version will be that Mr. Ewell accidentally killed himself. The novel ends with a comparison of this choice to the idea that it is a sin to kill a mockingbird.

It is not the first time Fordham illustrates a coming-of-age story with a crossover appeal or a narrative concerning sociopolitical topics like xenophobia. Before adapting Lee’s novel, Fordham published the Nightfall series (2013-2014) and The Adventures of John Blake: Mystery of the Ghost Ship (2017) written by Philip Pullman (b.1946). However, in this case, the stakes might be higher since any revision of a book that has been labeled as a modern American classic represents a challenge because of all the possible comparisons to the original.

Hutcheon (2006) claims that “if we know the adapted work, there will be a constant oscillation between it and the new adaptation we are experiencing; if we do not, we will not experience the work as an adaptation” (xv). As a result, an adaptation should not be judged in the lens of its fidelity to the source, but regarding its creativity. Even if it is recognizable because it derives from another oeuvre that has become part of our collective memory and so comes after it, an adaptation should not be a replica, a derivative or a secondary-order work (Hutcheon, 2006, pp. 4-9, 20).

Far from intending to compare the graphic novel with the original source or a different adaptation, this study aims at understanding the importance of a reinterpretation in a format that can bring new light, freshness, and accessibility to a story that, as we argue, deserves to be revisited.

For this purpose, the first and second sections are dedicated to the analysis of how space and time are portrayed in the story. The third and fourth are devoted to a study of the unique narrative resources, metaphors and symbols employed. The fifth section approaches the graphic novel from a sociopolitical perspective. Finally, the last part presents a few remarks regarding the advantages of the adaptation in the comic format.

Drawing Maycomb

To Kill a Mockingbird graphic novel style originates from the author’s interest in the long tradition of the Franco-Belgian bande-desinée (Andrew Nuremberg Associates, “Fred Fordham”, n.d.). Thus, Fordham combines characters that are not completely realistic- keeping a cartoonish touch, with entirely realistic landscapes.

In a short video, the artist explains how he visited Lee’s old home in Monroeville, Alabama -which was the inspiration for Maycomb where the story is set. As a result, what he draws in the adaptation is essentially a mirror image of that town (Harper Imprint, 2018, “To Kill a Mockingbird: A Graphic Novel”).

Pointner and Boschenhoff (2010) explain that pictures, as well as prose texts, have internal focalizers (p. 92). There is an image of a fence covering the whole page and showing the countryside painted in the background -to introduce the first part of the novel- which is presented from the perspective of Tom Robinson, whose hand is hanging from the fence. This is later confirmed when that same image reappears in the graphic novel, as the view from inside de prison when he tries to escape1.

Furthermore, Pointner and Boschenhoff (2010) argue that a prose text has to describe one event or setting after another, while the comic can show everything at once glance like in real life and so, convey immediacy showing the subject towards the space (pp. 89-90). The story narrated by Scout starts in the next page showing Maycomb from a high angle which in the following panels closes up to the protagonists2.

The display of the panels in the graphic novel is mostly conventional, but the color composition offers an original outlook. In the video, Fordham also explains how he did the drawings digitally, but manually added mixed watercolor washings to add texture to the pastel illustrations (Harper Imprint, 2018, “To Kill a Mockingbird: A Graphic Novel”).

The use of color in the graphic novel provides a vintage aesthetic that helps to recreate the period in which it is settled, while also highlighting important aspects of the narration. For example, flashbacks are mostly portrayed in black and white or in a gray color palette which brings a cinematic feeling to the reader experience. For instance, this technique is used when Scout remembers seeing Mr. Cunningham -a farmer- paying Atticus’ legal services with crops3 and when Tom Robison tells what happened with Mayella Ewell4.

Moreover, to highlight certain dialogues characters are usually drawn placed against a white background which directs the attention towards their discourse. On the other hand, silences are captured too. This can be seen in the scene at the porch near the end. Atticus and Scout are hugging while Boo Radley is sitting at their left on the swing and looking down5.

Through the graphic novel, other panels covering a big part of the page and displaying a long shot or a medium-long shot of the characters, and sometimes even combined with close up’s capturing their expressions, are presented to translate the quietness of a moment. The mirror resource is once again employed and intensified when the three children, Scout, Jem, and Dill, sat near the fish pool; the image shows what they are seeing reflected in the water -a full moon and clouds mixed with sea creatures and trees6. In fact, the graphic novel is filled with beautifully crafted illustrations of the countryside, natural representation of seasons, the weather changes and other sceneries of the town.

Apart from the color, the lights and shadows when characters are sitting in the porches during the summer or when a scene is presented at night, and through the panels dedicated to the fire at Mrs. Maudie’s house, highpoint the narration, making Maycomb another character in the story.

About time and space, Kukkonen (2013) claims that “rather than confusing what words and images can do, it seems that comics are a medium which capitalizes on the overlaps of these affordances” (p. 21). To represent the change of seasons, Fordham repeats the last image presented with a different aspect in the following panel. For example, the pages dedicated to the tree where the children find little gifts at the beginning of the school-year are followed by a panel enclosing a medium-long shot of the same tree, without leaves, while snowing7.

At your own pace

Films are another medium that represents images and words, time and space. However, as Pointner and Boschenhoff (2010) argue, it seems to be more dismissal towards comic adaptations than to film adaptations. While films are judged as separate works of art, comics are often judged on their faithfulness to the original literary source (p. 88).

Nevertheless, comics have advantages that films do not. “Comic works choreograph and shape time” (Chute, 2008, p. 454). It could be argued that so do films. However, in comics the author has not only to decide the general structure but what to put on each page. Hence, there is the possibility to juxtapose past, present, and future at one glance. It may happen in a prose text or a movie with flashbacks and flash-forwards, but not in such a direct way. For example, the Finch family history is presented in a splash page over a map pointing the route their ancestor took to arrive at Maycomb -a sailing ship is drawn in the upper background and this is followed by a forefront image of slaves working in a cotton plantation. On the page at the right, we see Maycomb from a high-angle accompanied by a caption where Scout mentions Atticus and her uncle. Finally, at the bottom down there is a drawing of the children silhouettes in black against a white background accompanied by a caption referring to how at present sometimes Jem feels estranged -and takes distance from the other children- when he remembers his mother who died when he was young (Fordham, 2018, p. 17)8.

This happens as well on the tier dedicated to the part of the trial when Tom Robinson is interrogated by Atticus Finch. When it arrives at the moment when he is getting ready to tell that Mayella kissed him, the first panel on the page shows Tom Robinson’s expression at present through a close-up while remembering the events; then at the center and covering most of the page, there is a panel of a medium-long shot of Mayella kissing Tom in the past; and ending with another close-up image, on the panel located at the bottom of the page, of Mayella’s expression during the trial while she is waiting to be exposed9.

Pointner and Boschenhoff (2010) point out that the comic has also fewer time restrictions than a film (p. 88). Therefore, it can compress everything in a few panels or either take several tiers to convey the slow passing of time of a particular sequence of actions. In the graphic novel, the moment when Scout accompanies Boo Radley back to his house is portrayed in this delicate way. The whole route taken is presented and even the moment when Boo is opening the door is extended10.

This display is important because it encourages readers to feel the pace from the point of view of the characters, which also happens when showing a routine. In the graphic novel, different drawings of the children playing during the summer are set on a splash page with fluidity11. Besides, the daily routine with a few variations is highlighted when Dill tries to convince Jem to go to Boo Radley’s house. One panel for each day shows how Dill repeats the same idea until Jem agrees to do it12.

Another example is when Scout says that the days in spring were longer and an image of Jem pushing her on a wheel swing hanging from a tree is colored black against a white background13. This moment captures routine and repetition in one panel.

As for pausing the narrative, exterior images are represented. For example, during the trial, after the tier dedicated to Atticus’ final questions during his interrogation to Tom Robinson, there is one panel showing the view of the court from outside. In the next panels, the trial is resumed with the prosecutor substituting Atticus14.

Furthermore, unlike a film where the duration of each scene is already established, in a comic, the reader is free to spend as much time as wanted or needed in each panel. Thus, even if the general order, pace, and frequency of a scene is predetermined by the artist’s conception, readers still have freedom concerning how they approach and interpret it.

As Kukkonen (2013) argues “unlike film, this allows readers to skim the pages and to jump back and forth between chapters if they choose to do so. Readers can also judge more conveniently how far into the novel or the comic they are in their reading and how long the story will last still” (p. 79). Even in terms of speed within the story, a reader can imagine how quickly a character is running or even, get dizzy watching the speed lines when Scout is moving inside a wheel, after been pushed by Jem, as part of a game15.

Retelling a familiar story

Narratives establish what can be said and what can be shown (Chute, 2008, p. 459). Kukkonen (2013) claims that it has been traditionally considered that words are destined to tell a story, while images are better suited for showing (p. 36). However, “in comics, readers pick up clues from both the images and the words, and mostly, the two modes work together toward unfolding the comic’s narrative in the panel sequence” (Kukkonen, 2013, p. 36).

As a result, words in comics are not only there to describe the setting and events, but they can also show the characters’ actions, especially through onomatopoeias. On the other hand, images “can tell through their composition and the characters’ bodies” (Kukkonen, 2013, p.38). In the graphic novel, Jem’s rage toward his bitter old neighbor -who insults Atticus for defending Tom- is not only shown through images of him destroying Mrs. Dubose’s camellias, but also because of a close up to his facial expression that captures interiority16.

Therefore, the input of a graphic novel adaptation of a popular story -that has already been adapted to a film and a play- relies on its ability to combine the best of both, the discourse with the visual features. Additionally, since the comic has fewer time restrictions than a movie or a play, it allows the author to adapt more of the story if wanted.

Still, “an adaptation which translates a classic for a new audience places it into a new context and thereby suggests new perspectives on a well-known text” (Kukkonen, 2013, p. 80). As stated, Fordham’s graphic novel keeps Scout Finch as the narrator, but it also shows scenes that in the story are not experienced by the narrator or the main characters and so, in Lee’s novel are not shown, but only told through a third person.

In this regard, Boo Radley’s story of why his family locked him in their house17, Dill’s made-up adventures to explain how he had escaped from his parents’ house and arrived at Maycomb18, Tom Robison’s account of what happened between him and Mayella Ewell, as well as his escape attempt and death, are shown -and not only told- in the graphic novel. The author of the graphic novel shows these scenes the way the characters that receive these messages might imagine them. Hence, the author as a previous reader of the novel -or source- shows his interpretation and puts himself in the place of the graphic novel audience.

Another way of appealing to the audience is by keeping the tension in the narration. For example, when Atticus is preparing to shot a dog with rabies that appears in their street, there is a subject-to-subject sequence of him pointing the gun and of the sick dog approaching, which keeps the tension and the anxiety of the moment19.

Tension is expressed through the artist’s visual interpretation, and symbols and metaphors that need to be deciphered, just like with written prose (Pointner & Boschenhoff, 2010, p. 96). Fordham chose to show rather than tell the adventure of the children trying to trespass the Radley’s property.

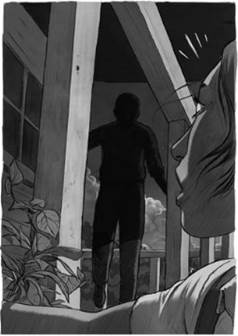

It immerses the reader more than text because, without words, the audience could feel directly how the characters are trying to remain silent -walking on their tiptoes-not to be discovered. Even when they see someone appear, he is portrayed as a shadow and so, Fordham retains the ambiguity of the moment. The children run back home after that and hear gunfire which breaks the attempt of remaining quiet while creating intrigue20.

Another moment that conveys tension and silence is when that same night after the adventure, Jem goes to look for his pants that he had lost in the Radley’s property. Fordham chooses not to show what Jem does, but keeps the focalization on Scout who remains at the porch waiting for his brother and frightened. When Jem finally comes back with his pants, he just goes to sleep leaving her, and the reader, uncertain of what had happened21. During the fire, Fordham again plays with uncertainty and surprise. On one page he shows a panel sequence of the kitchen with a kettle on the stove and then, the same image repeats surrounded by fumes coming from a pipe. On the next page, Atticus wakes Scout up in the middle of the night and gets her and Jem out of the house. This moment may trick the reader into believing that the Finch’s property is on fire. However, the next page shows that the house in front is the one on fire and then again the children, and perhaps the reader could assume that Mrs. Maudie is hurt. For instance, the first panel on the next page calms the audience with an image of Atticus telling his children that their neighbor is safe (Fordham, 2018, p. 83)22.

The mockingbird and other metaphors

Kukkonen (2013) argues that:

Comics are generally considered to be less “literary” than novels: they seem to be less ambiguous, they seem to represent less cognitive complexity, and they seem to offer a more straight-forward and less perplexing reading experience. But comics can also leave readers to draw their own conclusions, display a plurality of perspectives, and reflect on the features of their form (p. 84).

Fordham’s (2018) novel is not an exception. One of the most important lessons that Atticus teaches Scout is that “you never really understand a person until you climb into his skin and walk around in it” (p. 39). This speech is accompanied by the view from the Finch’s porch. Atticus and Scout watch Mr. Raymond, a man known for having a mixed-race family, riding a horse which renders Atticus’ speech literal23.

Birds are important symbols in the story too. When Scout as the narrator explains that the summer is coming and therefore, Dill, an image of the sky is presented with birds flying towards Maycomb. Dill who has also migrated to Maycomb appears in the following panel24. Another familiar metaphor in the story is the comparison of Boo Radley to a mockingbird. In the graphic novel, it is represented through sequential panels showing the exterior of the Finch’s house, while Scout and Jem discuss their views on the families of the town -which we know because of the speech bubbles that come out of the second-floor windows where their room is located. A mockingbird is standing on the fence outside the house. When Jem says that he understands why Boo Radley would prefer to stay at home, the mockingbird flies away (241)25.

In this respect, Chute (2008) explains how comics have a double-coded narrative because images and texts that are presented together may mean different, but remain complementary for narrative purposes (p. 459). This moment shows the hybridity of semantics that words and images could bring to a graphic novel because while Boo does not leave the nest, the mockingbird sings and then flies free.

Another moment of musical representation is when the Finch’s African-American housekeeper, Calpurnia, takes the children to her church. The members of the congregation sing gospels. This moment is presented without panels, but through lyrics conveyed in a fluid way that evokes movement, along with the singing faces -most of whom are doing it with eyes closed26.

The artist plays with eyes expression in the graphic novel once more, through the panels dedicated to Tom Robinson’s reaction after hearing his verdict. The word “guilty” is first shown in a black background which gives the sensation of hearing it from Scout’s perspective who is closing her eyes on the panel before, but at the same time, from Tom’s perspective who has his eyes closed in the upcoming three panels. Tom’s facial expressions, captured through close-ups, portray his feelings of deception, impotence, and frustration at that moment that ends up with another image of his face with tears in his open eyes - this time. The word guilty is repeated several times through those panels27.

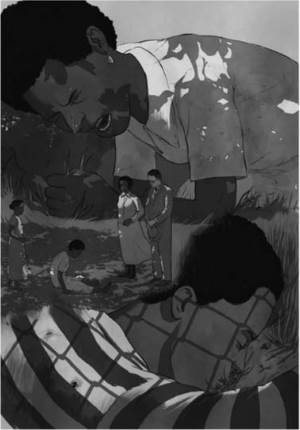

The next scene in which Tom Robinson reappears in the graphic novel is when he is trying to escape the prison and, as a consequence, he is shot dead. A double-page spread with striking drawings shows Atticus and Calpurnia telling the awful news to Tom’s wife while she is in the grass crying distraughtly. This drawing overlaps with a big image of her face highlighting her desperate expression and another showing Tom Robinson shot dead with his fingers touching the fence. His body blurs and dissolves with the grass. This fence image calls back to the scene that opens the whole book28.

The collage technique, with overlapped images of the same characters on different sizes, is once again employed when referring to Mayella’s loneliness during the trial29, as well as when Scout recognizes Boo Radley30 after the accident -with Jem and Mr. Ewell near the end of the story. Moreover, the way the characters are drawn helps to emphasize how they are struggling with mental health disorders.

Still, it should not be forgotten that To Kill a Mockingbird, no matter how touching and emotional it is as a story, it is also filled with humorous moments told from a precocious child’s point of view. This is not overlooked in the graphic novel where Scout sometimes appears doing pirouettes while playing with Jem. Humor is presented through form too, for example, when Scout reads a letter from Dill. The text is written in a drawn letter attaching Dill’s new stepfather photograph31.

White male privilege

Brenner (2011) claims that “comprehending a confusing topic is a key appeal of the graphic format” (p. 257). To Kill a Mockingbird certainly deals with difficult themes such as segregation, xenophobia, gender roles, rape, coming-of-age, social classes, and especially white male privilege.

Even though this story is settled in the thirties, the novel and its film adaptation appeared during the sixties -a period that witnessed the emergence of the Afro-American, Feminist and other important social movements.

The Broadway play and the graphic novel appeared in 2018. The play is for now only available to a few and maybe expanding to other theaters in the upcoming years. On the other hand, the graphic novel has already been published by fourteen different editorials around the world and thus, translated into several languages (Andrew Nuremberg Associates, “To Kill a Mockingbird (Graphic Novel)”, n.d.).

Thanks to the fact that the comic format has few length restrictions, it was able to include most of Harper Lee’s text. This means that unlike in the film, the references to gender roles and coming-of-age struggles that come from the point of view of the young characters are portrayed in the same significant way that the Tom Robinson case plot is represented. Hutcheon (2006) argues that “the context in which we experience the adaptation -cultural, social, historical- is another important factor in the meaning and significance we grant to this ubiquitous palimpsestic form” (p. 139). This means that the context also helps determine what is repressed or accentuated in terms of racial and gender politics (Hutcheon, 2006, p. 147).

For instance, at the linguistic and syntactic levels, the adaptation includes expressions that have been recognized as micro-aggressions. For example, when Jem refers to Scout as behaving like a girl in a diminishing way or when on the topic of religion, women are associated with impurity and sin. The adaptation also keeps references to behaving like a lady and what boys are not supposed to do -for instance, when Scout tells her cousin that boys don’t cook (Fordham, 2018, p. 98).

On a postscript note on why racial slur was translated to the graphic novel, Fordham (2018) explains how “…its dehumanizing power and ease with which was used -is central to understanding the themes of the novel” (p. 274). We believe that this decision also applies to other aforementioned offensive expressions rendered to the new format. After all, discourse shapes social constructions and is also a product of it.

Other choices regarding images in the graphic novel that are linked to the stated topics can be noticed, for instance, the first time a black person is mentioned in the narration. The panel only shows the person’s legs while walking, a choice that could be interpreted as trying to represent someone faceless for that society32.

However, when the trial is almost done, a panel of Tom Robinson’s face at the forefront is juxtaposed with a picture in the medium-front of Atticus telling the jury that is drawn in the background, to do their duty (Fordham, 2018, p. 221). This moment portrays white privilege in one panel, an appeal for accountability for what has been done, not only for the fact that the one guilty for abusing Mayella -which is never doubted in the narration- appears to be her own father, but also for the bigoted accusation.

Even if Hutcheon’s A Theory of Adaptation (2006) was published at the beginning of this century, we agree when she says that “the time is clearly right, in the United States, as elsewhere, for adaptations of works on the timely topic of race” (p. 143). It is still the right time because racial minorities, as the Black Lives Matter movement proves, have not stopped to be wrongly accused of crimes and to suffer from police brutality.

We would say that conceptions of women and gender roles are also timeless topics that need to be brought again to our context and not only because sexual aggressions to women, as the #MeToo movement shows, have not stopped to happen since the thirties or the sixties, but also because gender constructions and roles still rule our society at present.

In this context, boyhood and girlhood are portrayed on several pages in the story since the point of view of the story, as have been stated, comes especially from the Finch’s siblings. Their relationship with Dill especially captures these ideas. Fordham introduces on a splash page, first, a drawing of Dill on one knee proposing to Scout and then, another one of him playing alone with Jem, while Scout looks them from a distant point33.

Scout, as the narrator, explains that after proposing, Dill has neglected her even if she punched him a few times and that now she spends more time with her neighbor (Fordham, 2018, p. 52). Mrs. Maudie is shown on the next page with hard facial features working on her garden, while on the next panel she is sitting in her porch wearing a dress while Scout explains that this character is a sort of chameleon (Fordham, 2018, p. 53).

The confusing ideas towards sex and gender that Scout sees is that for a man being a boy and a gentleman is considered positive; on the other hand, for a woman being a girl or even a tomboy is not, she can only be a lady. This means that coming-of-age for a male and a female is different when regarded socially which is another topic captured in the graphic novel. Scout and Jem are drawn sitting on their beds on the same room back to back which captures the fact that Jem is becoming a teenager and that it is difficult for Scout to understand34.

This adaptation brings back a story that might be important during these times of reemergence of nationalistic governments and xenophobic and antifeminist movements and policies. As Chute (2008) claims “comics expand modes of historical and personal expression while existing in the field of popular” (p. 453). Form and politics intertwine in comics, it is a format capable of materializing history and thanks to this process, to aspire to ethical engagement too (Chute, 2008, pp. 457-459). To Kill a Mockingbird graphic novel is certainly not the exception.

Appealing to new audiences

Adaptations of a particular narrative emerge because of the continuing historical, socio-cultural and psychological relevance. As a result, any successful adaptation relies on giving freshness to a familiar story that the audience is willing to revisit. However, it must be accessible to audiences that are aware that it is an adaptation and know the source, as well as, to unknowing audiences (115-21).

Accessibility not only promotes the commercialization of the cultural product but also an important role in education since scholars and students “provide one of the largest audiences for adaptations” (Hutcheon, 2006, p. 117). This happens because adaptations “increase audience knowledge about and therefore engagement in the back story” and so, “this get-them-to-read motivation is what fuels an entire new education industry” (Hutcheon, 2006, p. 118).

Adaptations of books are considered educationally important for young readers because they are capable of bringing literature to a larger public, cutting away the literacy differences that come from a lack of access (Hutcheon, 2006, p. 120). Harper Lee’s novel has been read for a long time within formal education. Hence, the graphic novel as a new format could appeal to the public who is more interested in comics and also offer the feeling that it is a recreational reading different from the novel in the required lists.

Hatfield (2011) agrees that graphic novels powerfully motivate the young audience to read (p. 103). This author highlight that “the world’s most popular and influential comics have always been rooted in ideas about childhood and they had had millions of child readers” (Hatfield, 2011, p. 101). To Kill a Mockingbird graphic novel helps a story -told from the perspective of young characters- to age well and to appeal to the new generations. “Nowhere has the fissure between adult sanctioned and self-selected children’s reading been more boldly marked than in regard to comics” (Hatfield, 2011, p. 100). To Kill a Mockingbird novel has also suffered from a similarly controversial and contradictory reception since its publication eighty years ago from different audiences, due to the nature of the topics it covers, characters’ depiction and the use of offensive words. Therefore, the graphic novel might carry these burdens, but as have been analyzed in this article, it should not be dismissed.

Singing its heart out

As we have discussed, one of the advantages of the comic format is that it combines the best of other media: texts with images. In this particular case, the author has been able to translate most of what makes To Kill a Mockingbird a timeless story and also, add his viewpoint through the visual interpretation and the structure, whilst identifying himself with the reader.

The audience is also able to experience this familiar story in a new way. Readers have freedoms regarding the pace in which they decide to approach the text, each page, and panel. Besides, the format conveys immediacy regarding space and time -juxtaposing past, present, and future at one glance.

Therefore, the adaptation has merits that go from the visual to the pace, from what is shown and told in the narration, to the use of symbols and metaphors whilst directing the attention to the topics of white male privilege that needs to remain part of the agenda. The film adaptation focuses on the Tom Robinson case plot because of the length or maybe the time when it was adapted. Whereas the graphic novel is able to highlight other important parts regarding gender roles, as well as the fact that it is told from the perspective of a young girl.

The novel has been mandatory reading for a long time and thus, related to school, while the graphic novel emerges as a new format that could be more appealing and accessible for both the public that is familiar to the story and also the one that is not. Or even bring audiences together as a crossover.

To Kill a Mockingbird graphic novel shout not be discredited because of the lifelong challenges to Lee’s novel, or because the comic format has been underestimated, and neither for being an adaptation because as a mockingbird just does one thing, sings its heart out to us.