Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista argentina de cirugía

versão impressa ISSN 2250-639Xversão On-line ISSN 2250-639X

Rev. argent. cir. vol.113 no.2 Cap. Fed. jun. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.25132/raac.v113.n2.eras01ol.ei

Articles

The Science behind ERAS®

1 School of Medical Sciences. Dept of Surgery Örebro University Hospital & Örebro University. Suecia

Introduction

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) was started as a project by the author and the late professor Kenneth Fearon from Edinburgh, UK in 2001. Inspired by the multimodal approach to recovery proposed by Henrik Kehlet1, we decided to take these ideas further and look to the literature to seek all care elements that had been shown to help improve outcomes after major abdominal surgery2. The underlying hypothesis we had was that reducing the stress imposed by the injury of the operation in every possible way may help support the recovery of the patient and possibly also impact complications. We gathered colleagues with a similar interest and initiated what we named the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Study Group2. The group reviewed the literature and published the first consensus guideline on perioperative care for colonic resections3. By working together and pooling our clinical data we published a series of papers showing that with better compliance to the guidelines based on the current literature recovery was faster and complications fewer4 and less severe5. These results that have since been shown repeatedly6,7. This paper reviews the science behind ERAS.

What makes up an ERAS® Guideline?

The ERAS principles are based in the ERAS®Society Guidelines (for an udated list please see www.erassociety.org). The ERAS Guidelines for any given area of surgery assembles all elements that have support in the medical literature to support and improve recovery after that given type of procedure(s)8.

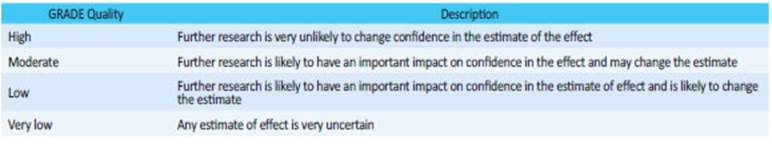

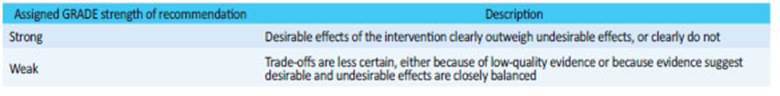

In short, the development of the ERAS®Society Guidelines follow a series of set steps. The first step involves the formation of a Guideline development group. Usually, this group is led by two individuals well trained in literature review and grading of evidence and actively developing the area of surgery. As a second step, a series of guideline topics to be reviewed are decided upon and alongside this step a limited number of collaborators are identified and invited to help review the literature. This group are ready to grade the level of evidence for any given care item and set a level of recommendation for its use. Thereafter the scoping of the review and the planning for the literature search is performed in a structured way using the PICO (population, Intervention, comparator and outcome) framework. The fourth step involves analysis of the quality of the available evidence. This is performed using the GRADE system. GRADE is the acronym for the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evolution approach8. The Quality of the evidence for each care item is assigned a GRADE quality (Table 1) and a GRADE strength of recommendation (Table 2). The recommendation can be strong even if the level of evidence low or very low if there is evidence to show that the effect, or cost-effectiveness is considerable and the risk of harm is negligible. This is followed by an independent review by two experts assigned from the ERAS®Society. Finally, if certain recommendations are hard to agree upon consensus generating methods such as Delphi is employed. Guidelines are brought up for discussion for revision every 2-3 years by the first or senior author to keep the guidelines updated. All ERAS®Society Guidelines are available at the Society’s web site (www.erassociety.org)

Do the guidelines work?

Several early papers suggested that employing the guidelines improved outcomes. Building the clinical evidence for their effectiveness has taken two approaches. The classical approach of reaching high level evidence is by randomized controlled trials. Several such trials were performed where several so-called bundled care protocols were tested versus what was called traditional care by the authors. Many of these studies were inspired by the first reports on Fast Track surgery from cardiac9 and major abdominal surgery10,11 using multimodal approaches to recovery. The problem with these reports was that they all had different protocols and different definitions of what encompassed traditional care. Nevertheless, it was by studying these studies in a meta-analysis that it could be shown that using more of the enhanced recovery care elements as opposed to fewer, that significant reductions in postoperative complications could be achieved12. This paper can be viewed as an important turning point in the development of the concept of ERAS by presenting of up to 50% reductions in complications after colorectal surgery. This has later been confirmed in meta-analysis of a growing body of evidence for colorectal, liver, gynecological and urological surgery13-16

Another approach to test the efficacy of the guidelines was by studying the outcomes in relation to how well the elements of the guidelines were being used, i.e. investigating the impact of complying to the guideline. This was first published in 2011 where a series of almost 1,000 consecutive open colorectal cancer surgeries in a single institution showed a clear dose - response relationship between compliance and fewer complications, shorter stay and fewer readmissions4. The same type of approach in more than double the number of patients in a multicenter and multi-national study reported almost the same findings and in addition showed that also severe complications were avoided with improved compliance5. More recent reports from Canada16, and from Spain6 report the same findings. Similar findings of better outcomes and faster recovery has also been reported in gynecological surgery17 and pancreatic resections18.

Other observations from these studies are that different hospitals have different views of what they regard as standard of care. This is very variable not only between countries but also within countries and between even single surgeons. This becomes evident when different studies report different elements having the greatest impact for the improvements and the outcomes. This is mostly related to which elements that were added to the care in that particular unit and not so much that only certain element could have the beneficial effect. That said it has been interesting to also note that in these studies some elements, such as preoperative carbohydrates often have been shown to have an impact on complications in these factor analyses, while this has not been evident in RCT’s where length of stay in major surgery has been the most positive outcome parameter19.

With larger materials and wider involvement of hospitals, thus broadening the variation in care delivery, such as in the Spanish study6, it becomes clear that the effect of ERAS is one of marginal gains. Many small gains from a multitude of care elements are brought together to get the maximum benefit and it seems that most if not all the elements of the protocols are meaningful to employ. Arguing that only a few elements are need to achieve the best results unversally is missing two very important aspects of modern surgery in the world. There is no standard of care universally - even if we would like it to be so. In fact the variability in what is standard of care will often vary with the surgeon and often based oin traditions. It is therefore not possible to know what could be effective to implement as far as ERAS guideline elements until you know what is actually being used in the first place. And secondly, it hard to find the rationale for denying the use of elements that have been shown to be effective, even if only to a small degree unless too costly. The cost has to be balanced in, but so far, cost analysis have shown that ERAS, because of its positive effects on complications and recovery time, saves a lot of cost for any provider and ultimately also the payer of the care20,21. In addition to the benefits in the immediate postoperative period, there are several reports of improved survival after surgery after major abdominal cancer surgery7,22,23 and orthopedic surgery24 associated with improved compliance to ERAS protocols. These findings are in line with previous large scale follow up studies showing an association with poor long-term survival in patients suffering postoperative complications25.

What makes ERAS work?

From the above it has been clear that the ERAS protocols have major impact on outcomes in the short and possibly also long term. The question is - what makes these protocols work? What are the mechanisms behind their effectiveness?

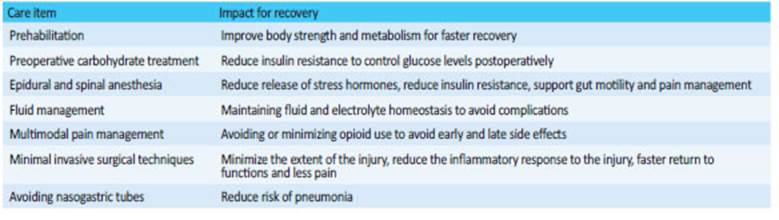

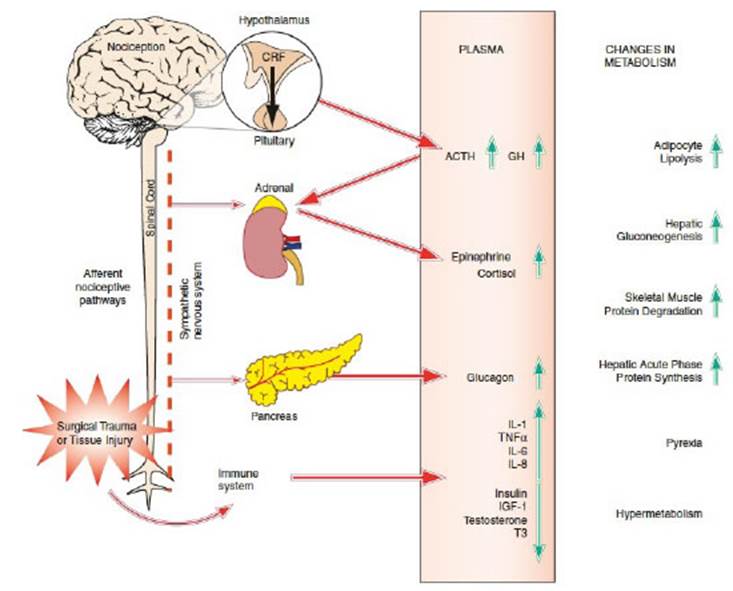

A very likely explanation for the effects lies in the mode of action and how the body reacts to the care items and how that impacts the reactions to the surgical stress. A Surgical operation is by definition causing an injury to the body to which the body reacts with a series of responses (Figure 1). These include rapid release of stress hormones and inflammatory responses that changes the entire body metabolism to a catabolic state, where the body is resistant to insulin26. The stress metabolism drains the body of glycogen, and releases protein from muscle as amino acids are reused for acute phase protein synthesis but also lost in the urine. These two metabolic reactions affect all muscle functions in the body impairing muscle function and strength, which in turn will affect vital functions such as breathing and movements. These changes are particularly dangerous for patients with poor reserves and frailty or underlying diseases. In parallel, the immune system is activated, and a massive release of pro-inflammatory cytokines are released that also impact body functions and in particular the immune systems.

Figure 1 Overview of the Stress Response to Surgery. CRF corticotropin-releasing factor, ACTH adrenocorticotropic hormone, GH growth hormone, IL interleukin, TNF tumor necrosis factor alpha, IGF insulin-like growth factor, T3 triiodothyronine. From Fawcett W J. Anesthetic Management and the Role of the Anesthesiologist in Reducing Surgical Stress and Improving Recovery. In Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®): A Complete Guide to Optimizing Outcomes Eds Ljungqvist O, Francis NK, Urman RD, ©Springer 2020 ISBN 978-3-030-33442-0. Used by permission

Many of the ERAS Guideline recommended care elements reduce the magnitude of these reactions or modify them, so that the reaction to a major operation resembles that of a much smaller and less invasive operation. By employing insulin sensitivity as a measure of the metabolic change occurring in surgery, it has been shown that a series of these elements have a major effect on these reactions23. By combining several of these elements insulin sensitivity can be kept close to normal even after a major open abdominal procedure, Table 3 27.

Another finding with the ERAS approach is that many of our traditional care elements actually do more harm than good3. For instance, the routine use of nasogastric tubes will result in more patients with pneumonia, routine use of surgical site drains and urinary drains serve no benefit but will hamper mobilization and may increase urinary infection rates. Using opioid based analgesia has resulted in a worldwide crisis with opioid addiction and represents one of the currently most discussed topics in medicine in the USA but now also around the globe28. ERAS protocols recommend opioid free or restricted multimodal non opioid pain medications as the alterative for pain management. Avoiding opioids in the postoperative phase also holds several short-term benefits by avoiding several side effects of opioid use such as nausea and vomiting, ileus, dizziness and delayed bowel movements.

Another major factor for improvement of care in surgery has been the change in fluid management principles. Modern care aim for fluid balance and avoiding both over- and underhydration29. From a surgical point of view the change to minimally invasive surgery (MIS) has had a major impact on outcomes and this technique is a cornerstone in modern ERAS protocols30. By minimizing the injury with MIS, the inflammatory responses are mitigated, as is insulin resistance - at least in some procedures31,32.

Future developments

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocols have been developed and shown to be effective for a wide range of operations and surgical specialties. The method of using the best available evidence form the literature has paved the way for guidelines that have been proven effective when put to use in daily clinical practice around the world. The development of the guidelines has also revealed that there are a number of care traditions that are outdated and that need change, while newer care principles should be brought to use in daily routine much faster than in the past. The Guideline reviews of the literature have also revealed that there are large gaps in the literature for perioperative care in many types of operations, and in often the best available evidence may have to be data transferred from other but similar operations. This means that a main challenge for the future is to build systems that allow the development of knowledge from high quality clinical trials. This can be done by joining forces and building systems that allow clinical trials to be performed in many units working together. Many of the questions that need to be answered have little or no commercial value, and this necessitates that these systems must allow studies to be run at low costs.

Conclusions

ERAS protocols are very effective in improving outcomes by employing a multi modal and multidisciplinary approach to practice evidence-based care. Many of the effective care elements that all contribute to reduce the negative impact of the injury caused by the operation. Recovery time and complications are reported reduced in a range of surgical specialties. These improvements in patient outcomes transforms to large cost savings, which is of particular importance with the current buildup of a surgical backlog as a result of COVID1933. The challenges ahead involve training units across the globe to employ the principles of ERAS and to build systems to produce high quality clinical research faster at a low cost.

Referencias bibliográficas /References

1. Kehlet H. Multimodal approach to control postoperative pathophysiology and rehabilitation. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78(5):606- 17. [ Links ]

2. Ljungqvist O, Scott M, Fearon KC. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery: A Review. JAMA surgery. 2017. [ Links ]

3. Fearon KC, Ljungqvist O, Von Meyenfeldt M, Revhaug A, Dejong CH, Lassen K, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery: A consensus review of clinical care for patients undergoing colonic resection. Clin Nutr. 2005;24(3):466-77. [ Links ]

4. Gustafsson UO, Hausel J, Thorell A, Ljungqvist O, Soop M, Nygren J. Adherence to the enhanced recovery after surgery protocol and outcomes after colorectal cancer surgery. Arch Surg. 2011;146(5):571-7. [ Links ]

5. Group tEC. The Impact of Enhanced Recovery Protocol Compliance on Elective Colorektal Cancer Resection: Results From an International Registry. Ann Surg. 2015. Published Ahead of Print. [ Links ]

6. Ripollés-Melchor J, Abad-Motos A, Díez-Remesal Y, Aseguinolaza-Pagola M, Padin-Barreiro L, Sánchez-Martín R, et al. Association Between Use of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Protocol and Postoperative Complications in Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty in the Postoperative Outcomes Within Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Protocol in Elective Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty Study (POWER2). JAMA surgery. 2020;155(4):e196024. [ Links ]

7. Ripolles-Melchor J, Ramírez-Rodríguez JM, Casans-Frances R, Aldecoa C, Abad-Motos A, Logrono-Egea M, et al. Association Between Use of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Protocol and Postoperative Complications in Colorectal Surgery: The Postoperative Outcomes Within Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Protocol (POWER) Study. JAMA surgery. 2019. [ Links ]

8. Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):383-94. [ Links ]

9. Engelman RM, Rousou JA, Flack JE 3rd, Deaton DW, Humphrey CB, Ellison LH, et al. Fast-track recovery of the coronary bypass patient. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;58(6):1742-6. [ Links ]

10. Bardram L, Funch-Jensen P, Jensen P, Crawford ME, Kehlet H. Recovery after laparoscopic colonic surgery with epidural analgesia, and early oral nutrition and mobilisation. Lancet. 1995;345(8952):763-4. [ Links ]

11. Kehlet H, Mogensen T. Hospital stay of 2 days after open sigmoidectomy with a multimodal rehabilitation programme. Br J Surg. 1999;86(2):227-30. [ Links ]

12. Varadhan KK, Neal KR, Dejong CH, Fearon KC, Ljungqvist O, Lobo DN. The enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathway for patients undergoing major elective open colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Nutr. 2010;29(4):434-40. [ Links ]

13. Greco M, Capretti G, Beretta L, Gemma M, Pecorelli N, Braga M. Enhanced recovery program in colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Surg. 2014;38(6):1531- 41. [ Links ]

14. Noba L, Rodgers S, Chandler C, Balfour A, Hariharan D, Yip VS. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Reduces Hospital Costs and Improve Clinical Outcomes in Liver Surgery: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24(4):918- 32. [ Links ]

15. Bisch SP, Jago CA, Kalogera E, Ganshorn H, Meyer LA, Ramírez PT, et al. Outcomes of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) in gynecologic oncology - A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2020. [ Links ]

16. Giannarini G, Crestani A, Inferrera A, Rossanese M, Subba E, Novara G, et al. Impact of enhanced recovery after surgery protocols versus standard of care on perioperative outcomes of radical cystectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 2019;71(4):309-23. [ Links ]

17. Wijk L, Udumyan R, Pache B, Altman AD, Williams LL, Elias KM, et al. International validation of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Society guidelines on enhanced recovery for gynecologic surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(3):237.e1-e11. [ Links ]

18. Roulin D, Melloul E, Wellg BE, Izbicki J, Vrochides D, Adham M, et al. Feasibility of an Enhanced Recovery Protocol for Elective Pancreatoduodenectomy: A Multicenter International Cohort Study. World J Surg. 2020;44(8):2761-9. [ Links ]

19. Smith MD, McCall J, Plank L, Herbison GP, Soop M, Nygren J. Preoperative carbohydrate treatment for enhancing recovery after elective surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;8:Cd009161. [ Links ]

20. Thanh N, Nelson A, Wang X, Faris P, Wasylak T, Gramlich L, et al. Return on investment of the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) multiguideline, multisite implementation in Alberta, Canada. Can J Surg. 2020;63(6):E542-e50. [ Links ]

21. Ljungqvist O, Thanh NX, Nelson G. ERAS-Value based surgery. J Surg Oncol. 2017;116(5):608-12. [ Links ]

22. Gustafsson UO, Oppelstrup H, Thorell A, Nygren J, Ljungqvist O. Adherence to the ERAS protocol is Associated with 5-Year Survival After Colorectal Cancer Surgery: A Retrospective Cohort Study. World J Surg. 2016;40(7):1741-7. [ Links ]

23. Pisarska M, Torbicz G, Gajewska N, Rubinkiewicz M, Wierdak M, Major P, et al. Compliance with the ERAS Protocol and 3-Year Survival After Laparoscopic Surgery for Non-metastatic Colorectal Cancer. World J Surg. 2019;43(10):2552-60. [ Links ]

24. Savaridas T, Serrano-Pedraza I, Khan SK, Martin K, Malviya A, Reed MR. Reduced medium-term mortality following primary total hip and knee arthroplasty with an enhanced recovery program. A study of 4,500 consecutive procedures. Acta Orthop. 2013;84(1):40-3. [ Links ]

25. Khuri SF, Henderson WG, DePalma RG, Mosca C, Healey NA, Kumbhani DJ. Determinants of long-term survival after major surgery and the adverse effect of postoperative complications. Ann Surg. 2005;242(3):326-41; discussion 41-3. [ Links ]

26. Ljungqvist O, Jonathan E. Rhoads lecture 2011: Insulin resistance and enhanced recovery after surgery. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2012;36(4):389-98. [ Links ]

27. Soop M, Carlson GL, Hopkinson J, Clarke S, Thorell A, Nygren J, et al. Randomized clinical trial of the effects of immediate enteral nutrition on metabolic responses to major colorectal surgery in an enhanced recovery protocol. Br J Surg. 2004;91(9):1138-45. [ Links ]

28. Levy N, Quinlan J, El-Boghdadly K, Fawcett WJ, Agarwal V, Bastable RB, et al. An international multidisciplinary consensus statement on the prevention of opioid-related harm in adult surgical patients. Anaesthesia. 2021;76(4):520-36. [ Links ]

29. Varadhan KK, Lobo DN. A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of intravenous fluid therapy in major elective open abdominal surgery: getting the balance right. Proc Nutr Soc. 2010;69(4):488-98. [ Links ]

30. Gustafsson UO, Scott MJ, Hubner M, Nygren J, Demartines N, Francis N, et al. Guidelines for Perioperative Care in Elective Colorectal Surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS((R))) Society Recommendations: 2018. World J Surg. 2019;43(3):659- 95. [ Links ]

31. Thorell A, Nygren J, Essén P, Gutniak M, Loftenius A, Andersson B, et al. The metabolic response to cholecystectomy; insulin resistance after open vs. laparoscopic surgery. Eur J Surg. 1995;162(3):187-92. [ Links ]

32. Wijk L, Nilsson K, Ljungqvist O. Metabolic and inflammatory responses and subsequent recovery in robotic versus abdominal hysterectomy: A randomised controlled study. Clin Nutr. 2016. [ Links ]

33. Ljungqvist O, Nelson G, Demartines N. The Post COVID-19 Surgical Backlog: Now is the Time to Implement Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS). World J Surg. 2020;44(10):3197-8. [ Links ]

Received: March 12, 2021; Accepted: March 24, 2021

texto em

texto em