Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista argentina de cirugía

versão impressa ISSN 2250-639Xversão On-line ISSN 2250-639X

Rev. argent. cir. vol.113 no.2 Cap. Fed. jun. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.25132/raac.v113.n2.eras02mcs.ei

Articles

Perioperative optimization, enhanced recovery and fast-track programs: why are they booming? What are these programs actually and how are they implemented into practice?

1 Servicio de Anestesiología, Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires.

2 Director de la Red de Investigación Perioperatoria de América Latina (RIPAL).

3 Director de la Academia de Medicina Perioperatoria de América Latina (AMPAL).

4 Vice-President of Implementation Programs ERAS Society. Presidente de ERAS Latam.

Every day, the number of publications about perioperative optimization, enhanced recovery or fast-track programs for increases. However, the use of these terms is not uniform, and in many cases the innovations of these protocols and their actual impact remain unclear. The aim of this introductory review to this special issue of the Revista is to develop the reasons for the boom of these programs, define them, describe how they are implemented into practice and the results of such implementation.

Why are perioperative optimization protocols booming?

The idea of achieving a better postoperative recovery, with fewer complications and for as many patients as possible, has always been the goal of every surgical team. However, in recent decades, this goal has become a need for the entire healthcare system.

Population growth and the increased volume of surgeries have far surpassed hospital infrastructure resulting in shortage of hospital beds worldwide1-5. Furthermore, the shift from fee-for-service payment model (revenues increase when more services are provided) for surgical services to pay-for-performance (payment per module) makes payers exert pressure for a sustainable medical practice6. In this setting, perioperative optimization programs are booming worldwide. These programs propose a solution to standardize surgical care and increase the volume of patients treated, and at the same time, they address the healthcare system need to offer high quality recovery, through a safe practice and with the necessary competitiveness to ensure sustainability over time7.

Fast-track, enhanced recovery, ERAS® and perioperative optimization. Who is who?

There is much confusion about the types of perioperative care programs, their methods and their goals. The terms fast-track, enhanced recovery, perioperative medicine and ERAS® programs are often used as interchangeable synonyms. This diverse terminology responds to a historical evolution of the term and to the different societies or study groups that have emerged around this new paradigm. By the end of the nineties, Professor Kehlet, from Denmark, published one of the first articles reviewing the main factors associated with postoperative rehabilitation (pain, gastrointestinal dysfunction, hypoxemia and immobilization) and the influence of traditional care on these factors (routine use of nasogastric tube, drains, restriction on oral intake after surgery)8. Just a few years later, the same author reported in the British Medical Journal the results of perioperative management under a new model of care which he called fast-track surgery9. This new model of care became stronger in different surgical teams, which quickly understood that the goal proposed by Kehlet was not the rapid or accelerated discharge of patients, but their enhanced recovery. Undoubtedly, enhanced recovery results in shorter length of hospital stay, but the main target is the quality and safety of perioperative care rather than the speed of discharge8. In this way, the term fast-track began to be replaced by enhanced recovery in different publications.

Also, at the beginning of the millennium different surgical teams, mainly from Scandinavia and the United Kingdom, led by Professor Ljungqvist, began to gather in study groups that promoted the review of traditional care and the multimodal and comprehensive approach to the surgical patient. These groups continue working together and formally constituted as the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society in 2010. This society develops its own protocols and training programs, which are then implemented under the supervision and training of the members of the society. Since then, the surgical programs certified by the scientific society have been referred to as ERAS® teams or programs. Over time, different societies worldwide, as ASER in the United States or SMaRT in Canada, have emerged with the same goal of promoting perioperative optimization.

In Argentina, there have been pioneer surgical teams in the use of optimized recovery guides. From previous publications of Revista Argentina de Cirugía, we have been able to learn about the experiences of Dr. Nari et al. in liver resections and that of the Hospital Británico team in colorectal surgery10-12. However, whether as part of an ERAS® program, Enhanced Recovery or fast-track protocols, the distinctive feature of a program aimed at perioperative optimization is not the specific technical content of its clinical guidelines, but the application of a working system with three fundamental elements:

1. The creation of a multidisciplinary team.

2. Systematic registration of perioperative care and outcomes.

3. Implementation of a continuous improvement cycle by the team using the data.

This cycle of continuous improvement is based on four elements that are used when addressing any problem or desired change: a) analyze data to make a diagnosis of the situation, b) plan an intervention, c) act on the plan made, and d) audit the effect7.

Implementation of protocols

The implementation of all the enhanced recovery programs begins with the creation of a multidisciplinary team with the aim of setting up weekly meetings to analyze the situation and plan the actions. These weekly meetings with members of different areas (anesthesiologists, surgeons, nurses, and nutritionists, among others) are key to addressing the different stages of surgical care as an indivisible process. The medical leader is usually a surgeon or an anesthesiologist, who holds the medical responsibility for the program to patients and authorities, sets the goals of the team, and manages the resources needed. The program coordinator schedules meetings, facilitates interaction between units and plays a key role in coordinating the stages (preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative care) and specialists (nutritionists, kinesiologists, among others) for the perioperative care for each patient. Finally, a member of the team is dedicated to collect systematically each patient data for continuous auditing.

In the case of the programs implemented through the ERAS® Society, the members will undergo a training phase which consists of four seminars separated by three active working periods with instructors from the ERAS® Society. The first seminar consists of an introduction to the main elements of the ERAS® Society guidelines and training in data entry. The period of action that follows this first seminar is the collection of data from the first 50 consecutive unselected cases of scheduled surgery after the first seminar. During this registration period, known as pre- ERAS stage, the multidisciplinary team continues with its routine care without changes, but all the information from these patients is entered into the ERAS® Society database. This group of Pre-ERAS patients is considered the baseline sample. The second seminar is mainly dedicated to reviewing the results of this baseline sample of patients with the instructors. The review of these patients in many cases shows a great discrepancy between what the surgical team believes that their common practice is and what actually happens. This phenomenon is not confined to our region: a recent study conducted in the United States showed that, on average, patients received only 55% of the guidelines recommendations that are allegedly followed by the medical centers13.

On the basis of the data collected (Pre-ERAS data), the team defines a target (e.g., to increase adherence to the elements of the guidelines or to reduce length of hospital stay) and how to achieve it. The second active working period then starts: the team works to increase the adherence to the practice that they had previously set as their objective and continues to systematically record these first ERAS patients (usually 10 patients). As expected, during the third seminar the team of trainees and the team of instructors will jointly review these 10 new patients, the adherence to the objectives set, and determine what new objectives will be achieved. Again, an active working period of the team begins during which patient data is collected to reach approximately consecutive 50 cases, thus reaching the fourth seminar. In this seminar the patients of the ERAS phase are reviewed and compared with the Pre-ERAS patients (50 vs. 50). The change in daily practice that the team had set is reviewed and the global adherence to the recommendations in the specific ERAS guidelines corresponding to the type of surgery is analyzed. If the overall compliance is greater than 70% or if the compliance doubles the Pre-ERAS sample, the training is considered complete, and that new unit is certified as ERAS team and published in the ERAS® Society website.

A unified database management system

As mentioned above, the ability to have reliable data is indispensable and distinctive of perioperative optimization programs. It is impossible to make a diagnosis of the situation and to detect and correct errors in the processes without data. However, with standard surgical care in our region (and in other locations), the information is often insufficiently collected by governments or large institutions, resulting in ineffective health policies that are a waste of money, time and energy. In our country, the two most common types of audits are the financial statement audit and the one carried out by physicians when they perform an analysis (usually retrospective) of their results for scientific dissemination. This second type of audit provides information that can contribute to our knowledge and to the care of patients but is not systematically performed as part of a method of work, consuming time and effort for each new question raised.

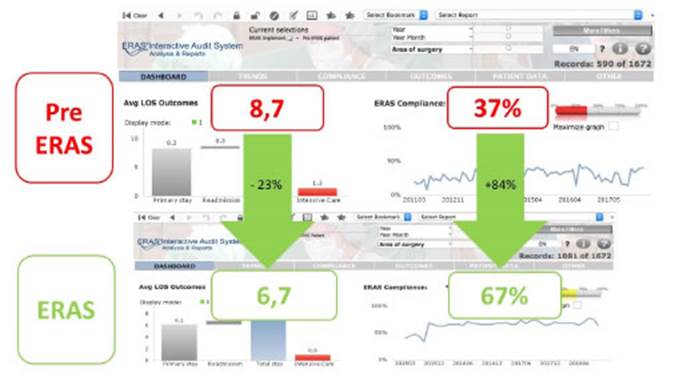

In many ERAS® Society programs, data collection of perioperative care is achieved through the ERAS Interactive Audit System (EIAS) an on-line, web based interactive software tool (Fig. 1). In this platform, each surgical team systematically reports records the data of each of its patients. Electronic data collection through EIAS avoids common problems as the lack of clear medical records and provides electronic storage that requires only access to the Internet. For each group of surgeries (e.g., colorectal, liver/biliary tract, or head and neck), the number of variables and definitions are the same in all centers worldwide. In other words, EIAS is the same database for any hospital worldwide and the information is recorded in the same way. This allows for a weekly diagnosis of the situation and auditing compared over time and with any other hospital or group of the ERAS® society (Fig. 2).

Figure 1 Initial dashboard of the ERAS Interactive Audit System. A summary of the different variables of the analyzed team is displayed. (Avg LOS: average length of hospital stay)

Figure 2 Comparative data of the Latin American ERAS programs. Above: results of 590 patients before the implementation of the ERAS program with an average length of hospital stay of 8.7 nights and an adherence to recommendations of 37%. Below: data from 1081 patients included in the ERAS programs with an average length of hospital stay of 6.7 nights and adherence to the recommendations of 67%. Period included 2015-2018.

During this year, a mobile tool for recording perioperative data will be implemented in Latin America. This application, called My Journey ®, is adapted to the reality of our region and facilitates data recording and patient education and provides an early warning system in case events occur (Fig. 3).

Figure 3 Dashboard of the mobile version of My Journey with a summary of a patient’s postoperative record.

Regardless of the type of commercial software used, systematic and standardized recording is a sine qua non condition to guide care and enhance research by surgical teams wishing to implement a perioperative optimization program.

Results of perioperative optimization programs world wide and in Latin America

Perioperative optimization programs were first developed for colorectal surgery and most of the experience is based on this type of surgeries. Different publications have consistently demonstrated a reduction in length of hospital stay in patients undergoing colorectal surgery following the ERAS programs14-16. These results have been observed in open surgery as well as in laparoscopic procedures17, in patients hospitalized in general wards or critical care units18 and even in high-risk patients19. There is strong evidence indicating greater reduction in length of hospital stay when the compliance with ERAS® guidelines is greater14,16. Similarly, the higher adherence to ERAS® guidelines has demonstrated a positive impact on postoperative complications and costs of care20-22. These positive outcomes in colorectal surgery have encouraged the implementation of fast-track recovery programs in other areas of general surgery and even other surgical specialties. Positive results have been observed in length of hospital stay and postoperative complications in thoracic surgery23, gastrectomies24 and liver resections25. In the same sense, the results in orthopedic26, urology27 and gynecologic oncology surgery28 are encouraging and demonstrate benefits attributable to the implementation of programs specifically designed to each specialty or type of surgery.

Fortunately, the perioperative optimization protocols have expanded over time in different specialties and hospitals across our continent. The starting point for ERAS® in Latin America was the implementation program led by Robin Kennedy, Olle Ljungqvist and Jennifer Burch in Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Argentina. This led to the development of the first ERAS® center of excellence in the region in 2015. In the same year, a team from Bogotá (Clínica Reina Sofía Org Sanitas) and another from Mexico (Hospital Civil de Guadalajara) joined this initiative, and today both are centers of excellence accredited by the ERAS® society. In 2016, two institutions in Uruguay (CAMOC in Carmelo and Médica Uruguaya Corporación de Asistencia Médica, in Montevideo) also joined the efforts to improve perioperative care in the region and are currently accredited as centers of excellence. Similarly, in 2016, two large medical centers in Brazil, which are regional benchmarks, started the implementation of their programs (Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein in São Paulo and Santa Casa de la Misericórdia in Porto Alegre). In 2018 and 2019, Clínica Alemana in Santiago de Chile and Instituto Nacional de Cancerología in México also joined the initiative. Like the worldwide experience, the implementation of and adherence to perioperative optimization protocols have demonstrated a reduction in postoperative complications and length of hospital stay in the region29,30. During this year, 8 new hospitals in Brazil will complete their ERAS® implementation program and we have started training at Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron through the ERAS LatAm online implementation program.

Conclusions

Perioperative optimization programs represent a paradigm shift in perioperative care. Each program offers evidence-based technical recommendations compiled in clinical management guidelines that are specific for the different types of surgery.

However, the guidelines alone are not enough to bring about the change needed to improve results. The key elements which are common to all the programs and fundamental to reach success are:

▪▪the creation of a multidisciplinary team

▪▪systematic and standardized registration of each case and continuous auditing of compliance using the EIAS database

▪▪implementation of a continuous improvement cycle (analyze, plan, act and audit)

The implementation of perioperative optimization programs has led to a reduction in complications, length of hospital stay and savings in care costs. These benefits have been observed in multiple areas of general surgery and even in other surgical specialties. In the current context of beds shortage and changes in payment systems, these programs will continue to receive increasing attention and funding from different health care agents and systems. This context opens an opportunity to improve our daily practice and our performance in the volume and quality of research.

Referencias bibliográficas /References

1. NHS. Admissions and Bed management in NHS acute [Internet]. 2000. Available from: https://www.nao.org.uk/report/inpatient-admissions-and-bed-management-in-nhs-acute-hospitals. [ Links ]

2. OECD (2019), Hospital beds (indicator). (Accessed on 30 Oct). 2018. [ Links ]

3. Israel Ministry of Health. Inpatient Institutions and Day Hospital Units in Israel. 2011. [ Links ]

4. Weiser TG, Haynes AB, Molina G, Lipsitz SR, Esquivel MM, Uribe-leitz T, et al. Surgical Services: Access and Coverage Estimate of the global volume of surgery in 2012: an assessment supporting im proved health outcomes. Lancet. 2012;385(Suppl 2):94305. [ Links ]

5. Meara JG, Leather AJ, Hagander L, Alkire BC, Alonso N, Ameh EA, et al. Global Surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet. 386(9993):569-624. [ Links ]

6. Hale D. Pay for Performance - Are You Prepared ? Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019;22(3):2015-7. [ Links ]

7. Ljungqvist O, Scott MF K. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery A Re view. Jama Surg. 2017;152(3):292-8. [ Links ]

8. Kehlet H. Multimodal approach to control postoperative patho physiology and rehabilitation. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78(5):606- 17. [ Links ]

9. Wilmore DW, Kehlet H. Clinical review: Recent advances: Manage ment of patients in fast track surgery. BMJ. 2001;322:473-6. [ Links ]

10. Nari G, Layun J, Mariot D, Viotto L, De Elias ME, López F, y col. Resultados de la aplicación de un programa Enhanced Reco very (ERP) en resecciones hepáticas abiertas. Rev argent cir. 2019;111(4):227-35. [ Links ]

11. Patron Uriburu J, Tanoni B, Ruiz H, Cillo M, Tyrrell C, Salomón M. Protocolo ERAS en Cirugía colónica laparoscópica: evaluación de una serie inicial. Rev Argent Cirug. 2015;107(2):63-71. [ Links ]

12. Nari GA, Molina L, Gil F, Vioto L, Layún J, Mariot D, y col. Enhan ced Recovery Afer Surgery (ERAS) en resecciones hepáticas abier tas por metástasis de origen colorrectal. Experiencia inicial. Rev argent cir [Internet]. 2016;108(1):1-10. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.ar/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2250- 639X2016000100002 [ Links ]

13. McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, Keesey J, Hicks J, DeCristofaro A KE. The Quality of Health Care Delivered to Adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2635-45. [ Links ]

14. Gustafsson UO, Hausel J, Thorell A L O, Soop M NJ. Adherence to the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Protocol and Outcomes After Colorectal Cancer Surgery. Arch Surg. 2011;146(5):571-7. [ Links ]

15. ERAS Compliance Group. The Impact of Enhanced Recovery Pro tocol Compliance on Elective Colorectal Cancer Resection. Ann Surg. 2015;261(6):1153-9. [ Links ]

16. Gillissen F, Hoff C, Maessen JM, Winkens B, Teeuwen JH, von Me yenfeldt MF et al. Structured Synchronous Implementation of an Enhanced Recovery Program in Elective Colonic Surgery in 33 Hospitals in The Netherlands. World J Surg. 2013;37(5):1082-93. [ Links ]

17. Levy BF, Scott MJ, Fawcett WJ RT. 23-Hour-stay laparoscopic colectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(7):1239-43. [ Links ]

18. Gustafsson UO, Oppelstrup H TA, Nygren J LO. Adherence to the ERAS-protocol is associated with 5-year survival after colorec tal cancer surgery: a retrospective cohort study. World J Surg. 2016;40(7):1741-7. [ Links ]

19. Delaney CP, Fazio VW, Senagore AJ R B, Halverson AL RF. Fast track postoperative management protocol for patients with high co-morbidity undergoing complex abdominal and pelvic colorec tal surgery. Br J Surg. 2001;88(11):1533-8. [ Links ]

20. Greco M, Capretti G, Beretta L GM, Pecorelli N B. Enhanced reco very program in colorectal surgery: ameta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Surg. 2014;38(6):1531-41. [ Links ]

21. Nelson G, Kiyang LN, Crumley ET, Chuck A, Nguyen T, Faris P, et al. Implementation of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Across a Provincial Healthcare System: The ERAS Alberta Colorec tal Surgery Experience. World J Surg. 2016;40(5):1092-103. [ Links ]

22. Varadhan KK, Neal KR, Dejong CHC, Fearon KCH, Ljungqvist O, Lobo DN. The enhanced recovery after surgery ( ERAS ) pathway for patients undergoing major elective open colorectal surgery : A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials q. Clin Nutr. 2010;29(4):434-40. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2010.01.004 [ Links ]

23. Madani A, Fiore JF Jr, Wang Y, Bejjani J, Sivakumaran L, Mata J et al. An enhanced recovery pathway reduces duration of stay and complications after open pulmonary lobectomy. Surgery. 2015;158(4):899-908. [ Links ]

24. Jeong O, Ryu SY PY. Postoperative Functional Recovery After Gas trectomy in Patients Undergoing Enhanced Recovery After Sur gery: A Prospective Assessment Using Standard Discharge Crite ria. Med Balt. 2016;95(14):e3140. [ Links ]

25. Song W, Wang K, Zhang RJ, Dai QX ZS. The Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) program in liver surgery: ameta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Springerplus. 2016;5:207. [ Links ]

26. Stowers MD, Manuopangai L, Hill AG GJ, Coleman B MJ. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery in elective hip and knee arthroplasty redu ces length of hospital stay. Anz J Surg. 2016;86(6):475-9. [ Links ]

27. Xu W, Daneshmand S, Bazargani ST, Cai J, Miranda G, Schuckman A KE et al. Postoperative pain management after radical cystec tomy: comparing traditional versus enhanced recovery protocol pathway. J Urol. 2015;194(5):1209-13. [ Links ]

28. Nelson G, Kalogera E DS. Enhanced recovery pathways in gyneco logic oncology. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;135(3):586-94. [ Links ]

29. Mendivelso Duarte F, Barrios Parra AJ, Zárate-López E, Navas-Camacho ÁM, Álvarez AO, Mc Loughlin S y cols. Asociación entre desenlaces clínicos y cumplimiento del protocolo de re cuperación mejorada después de la cirugía (ERAS) en procedi mientos colorrectales: estudio multicéntrico. Rev Colomb Cirugía. 2020;35(4):601-13. [ Links ]

30. Mc Loughlin S, Álvarez A, Falcão L, Ljungqvist O. The history of eras (Enhanced recovery after surgery) society and its develop ment in Latin America. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2020;47(1):1-8. [ Links ]

texto em

texto em