Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista argentina de cirugía

versão impressa ISSN 2250-639Xversão On-line ISSN 2250-639X

Rev. argent. cir. vol.113 no.2 Cap. Fed. jun. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.25132/raac.v113.n2.1550.ei

Articles

Transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy and parathyroidectomy vestibular approach (TOETVA TOEPVA): intial experience in Hospital Universitario Austral

1 Servicio de Cirugía de Cabeza y Cuello. Hospital Universitario Austral. Buenos Aires. Argentina.

2 Servicio de Ecografía Hospital Universitario Austral. Buenos Aires. Argentina.

Introduction

Kocher’s cervicotomy has been the classic approach for thyroid and parathyroid surgery since it was described in the late 19th century. Even though it provides excellent exposure of the central neck area, it unavoidably leaves a scar and is considered cosmetically inappropriate by some patients. The prevalence of thyroid nodules has increased in recent years due to the use of high-resolution ultrasound1,2 and patients’ perception of the scar has also increased and is usually different from the one recognized by surgeons.

During the last two decades, attempts have been made to reduce the size of the scar or to move it to less visible locations, as minimally invasive video-assisted thyroidectomy described by Miccoli3 and techniques to leave the scar outside the neck, such as endoscopic transaxillary hemithyroidectomy4 or endoscopic thyroidectomy via the areola approach5, with or without robotic assistance6. However, these techniques leave a scar, and most are not considered minimally invasive procedures because they require wide dissections to access the thyroid cell. The development of natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) facilitated its application in thyroid surgery; in 2008, Witzell7 reported the first sublingual approach in pigs and human cadavers. In 2010, Wilhelm reported8 his clinical application, with high morbidity; in 2011, Richmond described a robotic-assisted vestibular approach6 and, in 2012, Nakajo published a premandible approach, but with high rate of mental nerve injury9. In Thailand, Angkoon Anuwong improved the technique, modifying the position of the lateral ports, and in 2016 he published 60 cases, with optimal results and complications comparable to those of conventional thyroidectomy10. Since then, many centers have shared their experience and implemented training courses in all continents.

The Department of Head and Neck Surgery of Hospital Universitario Austral started a program for thyroid and parathyroid surgery via transoral approach in mid-2019, which included training with cadavers and live observations at the Johns Hopkins Hospital and dissections at the Chair of Anatomy of the School of Medicine of Universidad Austral.

The aim of this study is to report the initial experience with transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy and parathyroidectomy vestibular approach in Hospital Universitario Austral.

Material and methods

Between May 2019 and March 2020, 18 transoral procedures were performed in the Department of Head and Neck Surgery of Hospital Universitario Austral. The following variables were recorded: sex, age, history of thyroid cancer, nodule size and location, preoperative cytology, type of surgery, operative time, complications and tumor histopathology. The preoperative evaluation included routine laboratory tests, thyroid panel, calcitonin levels, laryngoscopy and neck ultrasound.

Inclusion criteria were benign thyroid nodule ≤ 6 cm, indeterminate nodules < 4 cm, gland volume ≤ 45 mL, euthyroid Graves’ disease, papillary thyroid carcinoma < 3 cm without evidence of extrathyroid extension, lymph node metastases and/or extension to adjacent organs, and parathyroid adenoma with 2 preoperative imaging localization tests with positive results. Thyroiditis, morbid obesity and nodules in the superior pole were considered relative contraindications. Endothoracic or retropharyngeal goiter, a history of neck surgery or radiotherapy, and medullary carcinoma were considered exclusion criteria.

The equipment used included endoscopy tower (4K), 0° and 30° endoscopes, bipolar electrocautery or harmonic scalpel of 23 cm, conventional instruments for endoscopy, 5-mm and 12-mm trocars and intraoperative neuromonitoring (NIM3, Medtronic ®).

All the patients signed a special informed consent form that included the specific complications of the technique. The protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Unit of Hospital Austral.

Surgical technique

General anesthesia, orotracheal intubation with a neuromonitoring endotracheal tube; patient lying in the supine position with the neck moderately hyperextended. Antibiotic prophylaxis with amoxicillin/ clavulanate, 30 minutes before making the incision. The patient’s oral cavity and neck are disinfected with povidone-iodine. A 10-mm incision is made in the mid-line of the oral vestibule, 1 cm above the labial sulcus. A blunt-tip tissue dissector is advanced through the mentalis muscle, until reaching the mental region and identifying the periosteum of the mandible. Next, 30 mL of lidocaine 0,5% in saline solution is injected through a Veress needle through the incision site into the central region of the neck. A subplatysmal working space is created using dilators of different sizes (up to 12 mm). A 12-mm trocar is placed through the central incision, a 30° laparoscope is inserted and CO2 is insufflated at a pressure of 6 mm Hg with a flow rate of 12 L/minute; two 5-mm trocars are placed through lateral incisions close to the commissures. The midline is opened, the strap muscles are retracted laterally by means of percutaneous sutures. The thyroid isthmus is sectioned and the anterior aspect of the trachea is exposed; the superior pole is released; the superior laryngeal nerve is identified and preserved by neurostimulation; the superior parathyroid gland is identified and preserved; the branches of the superior pedicle are ligated and sectioned with harmonic scalpel. The superior pole is retracted to the opposite side, the recurrent laryngeal nerve is identified when it enters the larynx using neurostimulation. The recurrent laryngeal nerve is dissected downwards perpendicular, the middle thyroid and branches of the inferior thyroid artery are ligated, Berry’s ligament is sectioned and the thyroid lobe is released watching the nerve. The specimen is extracted in an endobag through the central trocar and the nerve is tested to confirm its functional integrity. The cavity is washed, hemostasis is confirmed and hemostic material is placed (Surgicel®, Johnson). The incisions of the oral cavity are closed using 4/0 Polyglactin sutures.

Results

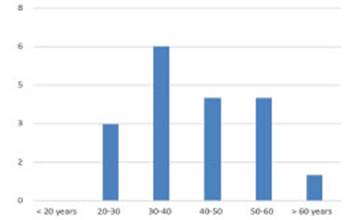

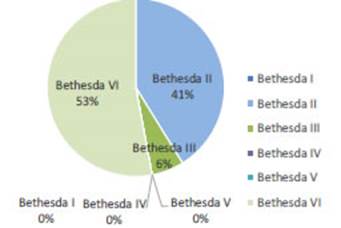

A total of 18 female patients were operated on; median age was 41 years (range: 22-60 years) (Fig. 1). Mean size of the nodules was 30 mm (range 4-50 mm) and mean gland volume on ultrasound was 24 mL. The cytology report according to the Bethesda system was category II in 7 cases, VI in 9 and indeterminate in 1; fine needle aspiration biopsies were not performed in parathyroid adenomas (Fig. 2).

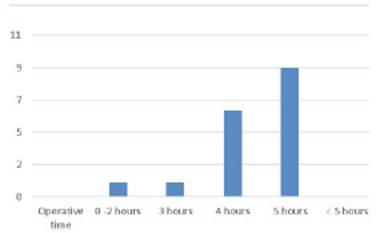

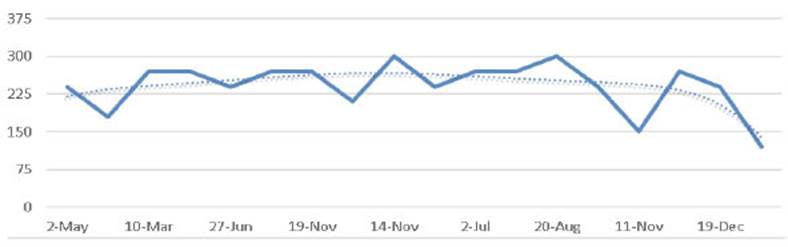

Thirteen lobectomies were performed (8 right lobectomies and 5 left lobectomies); 4 patients underwent total thyroidectomy, 1 with central lymph node dissection and 2 with parathyroidectomies; one patient presented a parathyroid adenoma and a benign thyroid nodule of 4 cm. One patient required conversion to conventional approach due to severe thyroiditis. Mean operative time was 260 minutes (range 120-300 minutes) for lobectomy and 262 minutes (range 240- 300) for thyroidectomy (Fig. 3).

The recurrent laryngeal nerve and the parathyroid glands were identified and preserved in all the cases; blood loss was not significant, and no drains were left in any of the 18 cases.

The definite histology was papillary carcinoma in 11 cases, benign nodular goiter in 6 and parathyroid adenoma in 2.

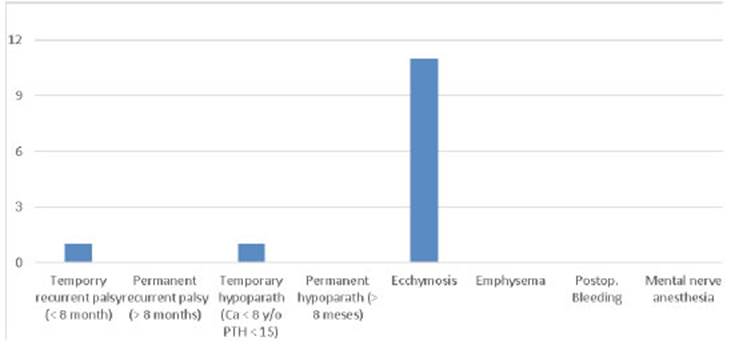

There were no major complications; 12 patients developed mild ecchymosis in the skin of neck and chin in 12 patient that resolved within a week; temporary hyperparathyroidism in 1 case; temporary recurrent laryngeal palsy in 1 case and temporary numbness of the mental region in 1 case (Fig. 4).

All patients were mobilized 4 hours after surgery, started oral intake and were discharged on postoperative day 1, without antibiotic treatment.

In the 2 cases undergoing total thyroidectomy due to cancer, thyroglobulin level 6 weeks after surgery was < 0.1 μIU/mL. The cosmetic result was excellent and all the patients were satisfied.

Discussion

Transoral video-assisted endoscopic thyroidectomy vestibular approach is a novel technique for the surgical treatment of certain diseases of the thyroid gland and parathyroid gland; it is appropriate for selected and cosmetically motivated patients11; its greatest achievement is the absence of neck scarring.

Over the past 20 years, several techniques have been described for the minimally invasive or remote approach of the thyroid gland; however, they have not been widely accepted due to their complications associated and the need for wide dissections to reach the thyroid gland4. After the original publication by Angkoon Anuwong10, the transoral technique rapidly expanded and many centers worldwide presented their experiences, including the group of the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore12, Fernandez Ranvier13 at Mount Sinai in New York and Anuwong, with his updated experience of 425 patients14. Furthermore, several systematic reviews have confirmed that the procedure provides good results, is safe and has low incidence of complications15,16.

Besides the absence of scar, the vestibular approach offers advantages over other remote accesses17 such as the short distance between the incision and the thyroid gland, subplatysmal dissection as in conventional surgery provides a midline exposure and equivalent access to both the right and left thyroid lobes and central compartment and visualization of the recurrent laryngeal nerve entering the larynx, its most constant anatomical landmark18,19. The procedure is reproducible, the equipment is available in most institutions, the learning curve is short, estimated in7-11 cases20,21 and the costs are considerably minor, since it does not require a robot. It also offers better visualization of the structures compared to conventional surgery, less postoperative pain and the possibility of early discharge of the patients.

Although our experience was limited, the results were similar to those of the reported series and comparable to those obtained with open thyroidectomy; there were no major complications and only one patient required conversion to the conventional approach. In contrast to the Asian series, drains were not used and length of hospital stay was significantly shorter22, with all patients discharged from hospital within 24 hours in line with those reported in the American series12. The use of antibiotics in the postoperative period varies considerably in the different publications23, with a range of 1 to 7 days; in our series, antibiotics were not indicated, and there were no procedure-related infections.

In this technique, proper patient selection is essential to ensure good results; ultrasound provides critical information on the size, location and characteristics of the nodules, which is essential to indicate this approach. In agreement with Tufano24, it is recommended for the surgeon to perform or be present during a preoperative ultrasound, as this happened in our series. Involvement of the superior pole, extension to the mediastinum, extra-thyroidal extension and evidence of thyroiditis are factors that hinder the implementation of this technique. The significance of thyroiditis is controversial, but it makes endoscopic dissection difficult20 and was the reason for the only conversion to conventional surgery in our series; the presence of suspicious or metastatic lateral cervical lymph nodes is an absolute contraindication for this approach. Graves’ disease represents a challenge and, although the literature is limited, apparently it is not an absolute contraindication. In the series published by Jitpratoom25 the results were comparable to those of open surgery, and in our series the only case operated on did not present any complications or major technical difficulties.

In case of hyperparathyrodism, it is necessary to perform the same preoperative imaging localization tests as for the conventional approach. In our experience, and in agreement with the literature26,27, only single and large adenomas (> 2 cm) with two preoperative imaging localization tests with positive results were treated; some recent reports include parathyroid hyperplasia as an accepted indication for this technique27.

The operative times were longer than those of conventional surgery, due to the learning curve; in agreement with other series20,21 operative times decreased as our experience progressed (Fig. 5).

Considering the rapid dissemination of this technique, it was necessary to establish basic requirements for the implementation of a transoral approach program24. The Johns Hopkins recommendations include the availability of high-volume thyroid surgeons (> than 25 cases per year), trained in endoscopy, ultrasound, cadaveric dissections, live observation of experienced surgeons, anatomical dissections; a specific informed consent and institutional support is also necessary. Because the conformation of the male larynx may hinder the approach, it is suggested to start the experience with female patients with small (< 4 cm), single nodules, ideally in the right lobe, but not in the superior pole and in the absence of thyroiditis; in our institution, all these requirements were met, as recommended by this working group.

Intraoperative monitoring of the recurrent laryngeal nerve during thyroid surgery is a matter of controversy; in the transoral approach, its major advantage is the identification of the nerve at the point of entry into the larynx; whereas in the conventional technique, the nerve is desected in downward, entailing greater risk, particularly when it penetrates through Berry’s ligament. During total thyroidectomy, if there is a loss of signal on the first side of resection, it is advisable to postpone completion of the other side to prevent bilateral palsy and possible tracheostomy28-30; it also demonstrates the functional integrity of the nerve at the end of the procedure29 which cannot be ensured by visual identification31; it can also help to identify and preserve the superior laryngeal nerve during ligation of the superior pedicle. In our experience neuromonitoring was used in all the cases, and its use is considered indispensable in this technique, while recognizing the higher costs associated. In our experience, only one patient operated on at the beginning of the program developed temporary palsy, although the percentages of permanent recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy with this technique varies widely in the literature22,23.

In most series, the number of cases with malignant nodules was very low (only 6% in the last series reported by Anuwong)14; our series revealed a clear predominance (> 60%) of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma, probably because we consider lobectomy alone as sufficient treatment in this group of patients with low risk of recurrence32-34. This approach can also be used in total thyroidectomies with central lymph node clearance, as in one case in this series, and although the literature assures that the number of resected nodes and postoperative thyroglobulin levels are similar to those of the conventional approach, further comparative studies are needed to ensure the procedure is oncologically safe35,36.

Finally, it is important to emphasize that morbidity in thyroid surgery is not limited to injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve or parathyroid glands. A study conducted in the UK37 reported that the cosmetic result has traditionally been underestimated and that what appears to be a good result to the professional does not necessarily coincide with the patient’s perception of his or her scar. Choi38 reported that 66% of his patients experienced symptoms related to scarring, and that quality of life measured with a dermatology index was impaired like in other chronic skin diseases because of the presence of the scar but not due to the characteristics or severity of the scar. The current demand for patient-centered care considering patients’ values and evidence -based medicine is satisfied when these aspects are considered; as Ralph Tufano states, it is important to keep in mind that “first do no harm”, that most nodules are benign and that scars are also a type of harm and should be avoided whenever possible. Nevertheless, once correct selection has been guaranteed, the primary indication and rationale for using the transoral approach in thyroid and parathyroid surgery is patient’s motivation to avoid a neck scarring39; we agree with this definition.

Conclusions

1. The transoral approach is a safe and feasible procedure that avoids skin scarring and offers excellent cosmetic results.

2. It can be implemented using conventional endoscopic equipment and has a short learning curve and similar complications to those of conventional thyroidectomy.

3. Although it constitutes an alternative for the treatment of low-risk papillary thyroid carcinoma, prospective studies with longer follow-up are needed.

4. Adequate selection of patients is a priority, as well as well-trained surgeons and the systematic use of intraoperative neuromonitoring.

Referencias bibliográficas /References

1. Mazzaferri EL. Management of a solitary thyroid nodule. N Engl J Med. 1993; 328:553-9. [ Links ]

2. Davis L, Welch HG. Current thyroid cancer trends in the United States. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014; 140:317- 22. [ Links ]

3. Miccoli P, Berti P, Raffaelli M, Materazzi G, Baldacci S, Rossi G. Com parison between minimally invasive video-assisted thyroidec tomy and conventional thyroidectomy: a prospective randomized study. Surgery. 2001; 130:1039-43. [ Links ]

4. Kim K, Kang S, Kim J, Lee C, Lee J, Jeong J, et al. Robotic transaxillary hemithyroidectomy using the Da Vinci SP robotic system: Initial experience with 10 consecutive cases. Surg Innov. 2020. [ Links ]

5. Yang J, Wang C, Li J. Complete endoscopic thyroidectomy via oral vestibular approach versus areola approach for treatment of thyroid diseases. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2015; 25: 470- 6. [ Links ]

6. Richmond J, Holsinger F, Kandil E, Moore M, Garcia J, Tufano R. Transoral robotic-assisted thyroidectomy with central neck dis section: preclinical cadaver feasibility study and proposed surgical technique. J Robot Surg. 2011; 5:279-82. [ Links ]

7. Witzel K, von Rahden B, Kaminski C, Stein H. Transoral access for en doscopic thyroid resection. Surg Endosc. 2008; 22:1871-5. [ Links ]

8. Wilhelm T, Metzig A. Endoscopic minimally invasive thyroidectomy: first clinical experience. Surg Endosc. 2010; 24: 17578. [ Links ]

9. Nakajo A, Arima H, Hirata M, Mizoguchi T, Kijima Y, Mori S, et al. Trans-oral video-assisted neck surgery (TOVANS): a new transoral technique of endoscopic thyroidectomy with gasless pre-mandi ble approach. Surg Endosc. 2013; 27:1105-10. [ Links ]

10. Anuwong A. Transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy vestibular ap proach: a series of the first 60 human cases. World J Surg. 2016; 40: 491-7. [ Links ]

11. Berber E, Bernet V, Fahey TJ III, Kebebew E, Shaha A, Stack BC Jr, et al. American Thyroid Association statement on remote-access thyroid surgery. Thyroid. 2016; 26:33-7. [ Links ]

12. Russell J, Christopher R, Razavi C, Mohammad Shaear M, Chen L, Lee A, et al. Transoral vestibular thyroidectomy: current state of affairs and considerations for the future. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019; 104:3779-84. [ Links ]

13. Fernández-Ranvier G, Meknat A, Guevara DE, Inabnet III W. Tran soral endoscopic thyroidectomy vestibular approach. JSLS. 2019; 23: 1-10. [ Links ]

14. Anuwong A, Ketwong K, Jitpratoom P, Sasanakietkul T, Duh QY. Safety and outcomes of the transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy vestibular approach. JAMA Surg. 2018;153: 21-7. [ Links ]

15. Chen S, Zhao M, Qiu J. Transoral vestibule approach for thyroid disease: a systematic review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018; 276:297-304. [ Links ]

16. Camenzuli C, Schembri Wismayer P, Calleja Agius J. Transoral en doscopic thyroidectomy: a systematic review of the practice so far. JSLS. 2018; 22: e2018.00026. [ Links ]

17. Dionigi G, Lavazza M, Wu C-W, Sun H, Liu X, Tufano R. Transoral thy roidectomy: Why is it needed? Gland Surg. 2017; 6:272-6. [ Links ]

18. Dionigi G, Tufano RP, Russell J, Kim HY, Piantanida E, Anuwong A. Transoral Thyroidectomy: advantages and limitations. J Endocri nol Invest. 2017; 40:1259-63. [ Links ]

19. Dionigi G, Chai Y, Tufano R, Anuwong A, Kim H. Transoral endo scopic thyroidectomy via a vestibular approach: Why and how? Endocrine 2018; 59: 275-9. [ Links ]

20. Luo J, Xiang C, Wang P, Wang Y. The learning curve for transoral endoscopic thyroid surgery: A Single Surgeon’s 204 Case Experi ence J Lap Adv Surg Tech. 2019 Volume 00, Number 00. [ Links ]

21. Razavi CR, Vasiliou E, Tufano RP, Russell JO. Learning curve for transoral endoscopic thyroid lobectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018; 159:625-9. [ Links ]

22. Anuwong A, Kim HY, Dionigi . Transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy using vestibular approach: updates and evidencesGland Surg. 2017; 6:277-84. [ Links ]

23. Fernández Ranvier G, Meknat A, Guevara D, Moreno Llorente P, Vidal Fortuny J, Sneider M, et al. International multi-institutional experience with the transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy vestibu lar approach. J Lap Adv Surg Tech. 2020; 30:1-6. [ Links ]

24. Razavi C, Tufano R, Russell J. Starting a transoral thyroid and parathyroid surgery program. Curr Otorhinolaryngol Rep. 2019; 7:204-8. [ Links ]

25. Jitpratoom P, Ketwong K, Sasanakietkul T, Anuwong A. Transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy vestibular approach (TOETVA) for Graves’ disease: a comparison of surgical results with open thy roidectomy. Gland Surg. 2016; 5:546-52. [ Links ]

26. Sasanakietkul T, Jitpratoom P, Anuwong A. Transoral endoscopic parathyroidectomy vestibular approach: a novel scarless parathy roid surgery. Surg Endosc. 2017; 31:3755-63. [ Links ]

27. Hurtado-López LM, Gutiérrez-Román SH, Basurto-Kuba E, Kuauh yama Luna-Ortiz K. Endoscopic transoral parathyroidectomy: ini tial experience. Head Neck. 2019; 4: 3334-7. [ Links ]

28. Erol V, Dionigi G, Barczyński M, Zhang D, Makay O. Intraoperative neuromonitoring of the RLNs during TOETVA procedures. Gland Surg 2020; 9 (Suppl 2):129-35. [ Links ]

29. Inabnet III W, Suh H, Fernández-Ranvier G. Transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy vestibular approach with intraoperative nerve monitoring. Surg Endosc. 2017; 31:3030. [ Links ]

30. Schneider R, Machens A, Lorenz K, Dralle H. Intraoperative nerve monitoring in thyroid surgery-shifting current paradigms. Gland Surg. 2020; 9(Suppl 2):S120-S128. [ Links ]

31. Wang Y, Yu X, Wang P, Miao C, Xie Q, Yan H, et al. Implementa tion of intraoperative neuromonitoring for transoral endoscopic thyroid surgery: a preliminary report. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2016; 26:965-71. [ Links ]

32. Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, Doherty G, Mandel SJ, Niki forov YE, et al 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differenti ated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016; 26:1133. [ Links ]

33. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: thyroid carcinoma. Version 1.2020. [ Links ]

34. Perros P, Boelaert K, Colley S, Evans C, Evans R, Gerrard Ba G. Guidelines for the management of thyroid cancer. Clinical Endo crinology. 2014; 81 (Supplement 1):1-122. [ Links ]

35. Ahn J, Yi J. Transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy for thyroid carci noma: outcomes and surgical completeness in 150 single-surgeon cases. Surg Endosc. 2020; 34: 868. [ Links ]

36. Yi J, Yoob S, Kim H, Yu H, Kim S, Chai Y, et al. Transoral endosco pic surgery for papillary thyroid carcinoma: initial experiences of a single surgeon in South Korea. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2018; 95: 73-5. [ Links ]

37. Arora A, Swords C, Garas G, Chaidas K, Prichard A, Budge J, et al. The perception of scar cosmesis following thyroid and parathy roid surgery: a prospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2016; 25:38- 43. [ Links ]

38. Choi Y, Lee JH, Kim YH, Lee YS, Chang HS, Park CS, Roh MR. Impact of postthyroidectomy scar on the quality of life of thyroid cancer patients. Ann Dermatol. 2014; 26:693-9 [ Links ]

39. Razavi CR, Russell JO. Indications and contraindications to tran soral thyroidectomy. Ann Thyroid. 2017; 2 (5): pii: 12. [ Links ]

texto em

texto em