Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista argentina de cirugía

versão impressa ISSN 2250-639Xversão On-line ISSN 2250-639X

Rev. argent. cir. vol.114 no.3 Cap. Fed. set. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.25132/raac.v114.n3.1656

Articles

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on a university-based residency program in plastic surgery

1 División Cirugía Plástica, Hospital de Clínicas José de San Martín. Ciudad de Buenos Aires. Argentina

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on training in plastic surgery, resulting in a crisis in medical education, surgical training and teaching in general, which needs to be analyzed and evaluated1. Some of the factors contributing to this issue include loss of work hours due to sick leave, changes in rotations to limit exposure, reduction in face-to-face appointments with patients, and reassignment of residents to areas not related with their specialty2.

Several questionnaires conducted among residents in plastic surgery worldwide coincide that more than 80% of the respondents reported a 75% reduction or greater in their scheduled surgical activity3-5. Many strategies, such as virtual classes, discussion of surgery videos, surgical simulation training and the use of multimedia tools have been implemented worldwide in an attempt to mitigate this complex situation6,7. In our setting, two university-based hospitals have reported their experience in reorganizing the residency program in general surgery during the pandemic to protect health of staff and patients and ensure adequate coverage of the tasks of the department, while maintaining the academic activity8,9. The measures implemented included division into work groups, use of telemedicine, prolongation of the training year to September 2021, and implementation of changes in the residency program with greater influence of virtual resources for learning and evaluation8,9.

This unprecedented scenario forced redefining plastic surgery care with medical, ethical and social responsibility, prudently managing the limited resources of staff, medical supplies and personal protective equipment10-12. In line with these considerations, our department implemented a plan to reassign healthcare functions and roles as the usual surgical activity was reduced. As can be expected, this had direct consequences on residents’ training and hands-on activities. To understand how much these activities were affected, it is necessary to quantify the phenomenon described.

The aims of the present study were: 1) to compare healthcare activity (surgeries and consultations) carried out before and during the pandemic, and quantify the percentage change between both periods, and 2) to describe the adaptation strategies implemented by the department in healthcare and educational activities of the residency program to compensate for the deficit in hands-on activities.

Material and methods

We conducted a retrospective, observational and descriptive study. Surgeries performed between March 2019 and February 2021 by the department of plastic surgery, and those performed together with the departments of surgical oncology, digestive surgery, vascular surgery, orthopedics, gynecology, urology and neurosurgery, were recorded. The information was obtained from the operating unit database. The periods were divided into pre-pandemic (March 2019-February 2020) and intra-pandemic (March 2020-February 2021) and the change in the number of procedures was analyzed. The following procedure categories were considered for the analysis: elective, emergency, cosmetic and reconstructive procedures, each one stratified according to the type of intervention performed. The formula of percentage change was used, and tables and bar charts were created to compare the results. The percentage change in outpatient consultations and academic and scientific activities was calculated.

Results

Elective and non-urgent surgeries were postponed as of March 19, 2020. The team made up of residents and staff physicians worked on a case-bycase basis and in a comprehensive fashion to assign priorities to reduce the risk of exposure and infection for healthcare workers and patients. Surgical activity was rearranged, focusing on reconstructive surgery after cancer and on the treatment of wounds and acute traumatic injuries, while all cosmetic procedures were suspended.

The total number of plastic surgery procedures was reduced by 59% between the pre-pandemic and intra-pandemic periods (n = 368 vs. n = 152).

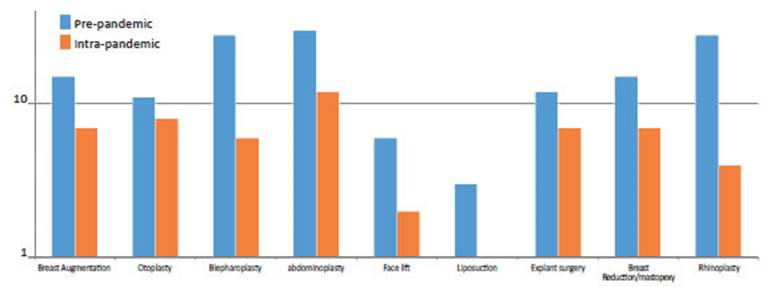

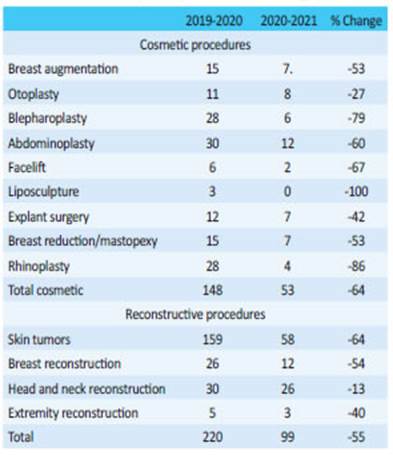

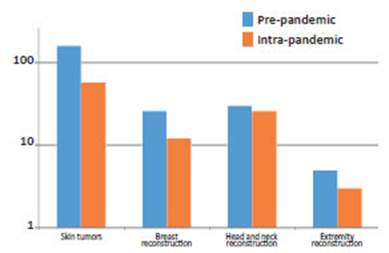

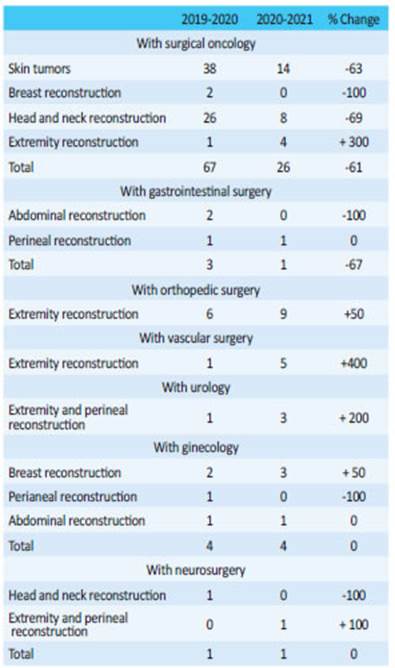

Scheduled cosmetic procedures (Table 1 and Figure 1) decreased by 64% (n=148 vs. n=53), with the greatest impact on liposculpture (-100%), rhinoplasty (-86%) and blepharoplasty (-79%). Cosmetic surgery could only be performed once the government removed the restrictions and was thus confined to the final portion of the period analyzed. Reconstructive surgeries (Table 1; Figure 2) decreased by 55% (n = 220 vs. n = 99). Percent reduction was distributed as follows: skin tumors -64% (n = 159 vs. n = 58), breast reconstruction -54% (n = 26 vs. n = 12), extremity reconstruction -40% (n = 5 vs. n = 3), head and neck reconstruction -13% (n = 30 vs. n = 26). Multidisciplinary reconstructions (Table 2) performed with other specialists showed different patterns. Surgeries performed with the Department of Surgical Oncology decreased by 61% (n = 67 vs. n = 26): skin tumors -63% (n = 38 vs. n = 14), breast reconstruction -100% (n = 2 vs. n = 0), head and neck reconstruction -69% (n = 26 vs. n = 8); yet extremity reconstruction increased by 300% (n = 1 vs. n = 4). Surgeries performed with the Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery decreased by 67% (n = 3 vs. n = 1), with 100% reduction in abdominal reconstructions (n = 2 vs. n = 0); the number of reconstructions of perineal defects remained unchanged (n = 1). Conversely, extremity reconstructions performed with the Department of Orthopedic Surgery increased by 50% (n = 6 vs. n = 9), and those carried out with the Department of Vascular Surgery increased by 400% (n = 1 vs. n = 5). Surgeries performed with the Department of Urology (extremity reconstructions and reconstruction of perineal defects) increased by 200% (n = 1 vs. n = 3). The number of reconstructions with the Department of Neurosurgery (n = 1 vs. n = 1) and Gynecology (n = 4 vs. n = 4) remained unchanged; in this case, breast reconstructions increased by 50% (n = 2 vs. n = 3), abdominal reconstructions remained unchanged (n = 1 vs. n = 1) and reconstruction of perineal defects decrease by 100% (n =1 vs. n = 0).

Below, we detail the number of surgeries to be performed as established by Federación Iberolatinoamericana de Cirugía Plástica (FILACP)27, Sociedad Argentina de Cirugía Plástica, Estética y Reparadora (SACPER) and Universidad de Buenos Aires (UBA), and compare them with the number of surgeries performed by each resident per year in our Department:

▪ First year: local grafts and flaps, mininimum n = 20, -64% (n = 80 vs. n = 29); body contouring abdominoplasty/ brachioplasty/liposuction/lipoinjection minimum n = 15, -64% (n = 17 vs. n = 6); ulcer debridement and care of burn injuries, minimum n = 20, 112% increase (n = 48 vs. n = 102), otoplasty, minimum n = 5, -33% (n = 6 vs. n = 4).

▪ Second year: breast augmentation/placement of tissue expanders and myocutaneous flaps for breast reconstruction, minimum n = 20, -52% (n = 21 vs. n = 10); ophtalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery; minimum n = 10, -79% (n = 14 vs. n = 3); maxillofacial surgery; minimum n = 15, -13% (n = 15 vs. n = 13); extremity reconstruction -33% (n = 3 vs. n = 2).

▪ Third year: rhytidectomy minimum n = 3, -67% (n = 3 vs. n = 1); mastopexy/breast reduction/breast impact revision; minimum n = 12, -50% (n = 14 vs. n = 7), rhinoplasty, minimum n = 12, -86% (n = 14 vs. n = 2), face reconstruction.

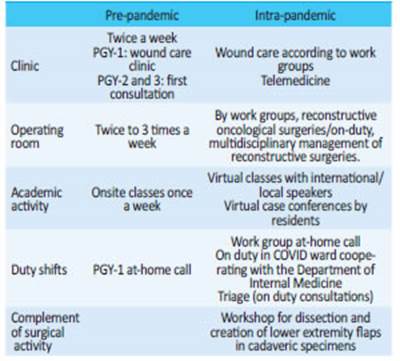

Although there was an overall reduction in emergency surgeries of 16% (n = 19 vs. n = 16), head and neck surgeries increased by 20% (n = 10 vs. n = 12) due to maxillofacial trauma requiring surgery. In the early stages of the pandemic, staff functions were structured with focus on safety and on preparing the healthcare system for duties different from the usual ones. Staff physicians and residents were assigned for evaluation of patients presenting with COVID-19 symptoms at triage and were on duty in COVID wards. The department was reorganized (Table 3) by scheduling working hours to reduce potential exposures and ensure appropriate rest. Work teams were rotated weekly with minimal contact between groups to avoid cross-contamination and ensure a cohort of healthy personnel available to work in the event of infection. Residents were divided into two work groups. Each group was made up of one postgraduate-year 3 resident, one or two postgraduate-year 2 residents and one postgraduate-year 1 resident, with intermittent on-site activity, i.e., one week every 15 days, to allow for the isolation of one of them in case of close contact with a SARS-CoV-2 positive case. Each group performed reconstructive surgeries during their corresponding week, mainly together with surgical oncology, and were at-home call for complex facial injuries, facial fractures and decubitus ulcers.

The pandemic forced alternative homebased roles for the staff, such as research projects, telemedicine, and educational teleconferencing. Since the beginning of lockdown phase 0, a series of webinars with local and international speakers were implemented; each session lasted two to three hours and was held from Monday to Friday mornings. Later, the activities included case conferences on reconstructive and cosmetic surgery in which the chief resident presented the case and the resident had to answer how he/she would manage it and explain the preoperative marking. They were performed through virtual platforms with screen sharing and real time editing that allow how to draw preoperative marking for a given procedure.

With the return to on-site training in more advanced stages, but still with scheduled procedures suspended, a dissection workshop was held to recognize anatomical structures and create lower extremity flaps using above-knee amputation specimens. Practice on cadaveric models resembles the real situation since it involves handling of tissues and the use of specific instruments. These workshops were held in compliance with social distancing measures and wearing personal protective equipment. The activity in outpatient clinics was reduced to limit the risk of viral exposure for patients, family members, and health care workers. Face-to-face consultations decreased by 50% during the pandemic compared with consultations before the pandemic (n = 2603 before vs. n = 1308). Consultations and followup services were carried out through a system of telephone calls, e-mails with pictures, text messaging and video calls. Approximately 400 teleconsultations were performed during the first 6 months of lockdown. The goal was to keep communication channels open with surgical patients to prevent overloading the emergency department or hospital hotlines.

There was a 112% increase in consultations for decubitus ulcers (n = 96 vs. n = 204), with a greater incidence of anterior pressure ulcers attributed to prone positioning (n = 0 vs. n = 9). There were also important variations in academic activity, with an increase in the production of scientific papers for national and international congresses and conferences. Before the pandemic period (March 2019-February 2020), 5 papers were submitted, while 13 were submitted during the pandemic (March 2020-February 2021; 160% increase). In addition, some papers submitted to journals are still under review.

Discussion

Although plastic surgery is not directly related with the care of COVID-19 patients, the overload of the health system made it necessary to incorporate physicians from different specialties to provide care against the virus13-17. At the same time, healthcare activity continued in several emergency and elective situations in which human life or viability of an extremity were at risk18. Treatment of acute injuries, burns, and craniofacial and limb trauma remained active. Consultations concerning the aftereffects of critically ill bedridden patients, such as decubitus ulcers, also increased.

The initial drop in the volume of scheduled surgeries, the cancellation of face-to-face educational activities, and the need to reassign residents to support the hospital’s critical services, raised concerns about the feasibility of achieving the competencies required to become a specialist as stipulated in the residency program5. Traditional training in plastic surgery consists of technical skills, surgical decisionmaking and the necessary knowledge to provide safe patient care19. Competence in these modalities is ensured by requiring case minimums and oral and written examinations20. In this regard, we quickly realized that the learning modality had changed19,21 and implemented an online training program that included webinars and interdisciplinary virtual case conferences. The contingency plan also incorporated tutorials and hands-on training in the cadaveric laboratory.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on surgical care, education, training and teaching has been enormous22,23. The cancellation of elective surgeries and restrictions to the presence of nonessential personnel in the operating room affect and will inevitably continue affecting residents’ handson surgical experience, skills and number of cases, thereby significantly disrupting their training24,25. These unfavorable circumstances require creativity, flexibility and innovation. It is important to find new models for providing education, teaching and training in surgery22,26. In Argentina, the first step required to develop a plan to revert the deficit is to make a correct diagnosis of the situation. Hospital de Clínicas José de San Martín, as a university-based hospital of the UBA and location of the specialist course, is an indicator of how the pandemic has impacted on education in the specialty. Quantifying this impact is a fundamental first step. Difficulties are encountered throughout all the educational stages, from undergraduate training to core residency programs, subspecialties and fellowship programs. Each of these stages has particular needs, obstacles and subtle differences that must be addressed and considered when planning a possible solution.

Our department has 7 residents and 1 fellow in microsurgery, and all of them have experienced a decrease in hands-on training and participation in surgery. The division of our analysis under the premise that each year of the residency program involves dealing with different conditions, allows identifying the most affected aspects in each of them, highlighting those cases where the minimum competencies were not achieved.

Conclusion

Based on the experience we have here described, we can affirm that there was a marked decrease in healthcare activities at all the levels of the residency program which should be compensated for in the future. Identifying the deficit and segregating it by type of procedure is an important step to prioritize the areas that need to be supported. While the overall reduction in surgeries is about 60%, it was greater in some procedures as breast reconstruction, liposculpture, rhinoplasty, blepharoplasty and facelift surgery and should be corrected. Quantifying this decline is a fundamental first step for developing a plan to reverse this problem.

The strategies implemented by our department in the academic and healthcare areas during the lockdown are elements that could be taken into account by other centers undergoing similar situations.

This study describes a complex scenario with figures and suggests an approach to deal with it. Future studies are needed to determine the best strategies to address this problem. An interdisciplinary approach, creativity and the involvement of educational authorities, in light of objective data illustrating a complete picture, are probably some of the elements necessary to find a solution.

Referencias bibliográficas /References

1. Hau HM, Weitz J, Bork U. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Student and Resident Teaching and Training in Surgical Oncology. J Clin Med. 2020;9(11). [ Links ]

2. Reed AJM, Chan JKK. Plastic surgery training during COVID-19: Challenges and novel learning opportunities. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2021;74(2): 407-47. [ Links ]

3. Kapila AK, et al. The Impact of Coronavirus Disease 2019 on Plastic Surgery Training: The Resident Perspective. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8(7): E3054. [ Links ]

4. Kumar S, More A, Harikar M. The Impact of COVID-19 and Lockdown on Plastic Surgery Training and Practice in India. Indian J Plast Surg. 2020;53(2): 273-9. [ Links ]

5. Zingaretti N, et al. The Impact of COVID-19 on Plastic Surgery Residency Training. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2020;44(4): 1381-5. [ Links ]

6. Hamidian Jahromi A, Arnautovic A, Konofaos P. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Education of Plastic Surgery Trainees in the United States. JMIR Med Educ. 2020; 6(2): E22045. [ Links ]

7. Yan M, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on a plastic surgery residency education program: Outcomes of a survey. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2021;74(3): 644-710. [ Links ]

8. Mastroianni G, Cano Busnelli VH, Huespe PE, Dietrich A, Beskow A, de Santibañes M, Pekolj J. Cambios en el Prograna de Fromación Quirúrgica en la era COVID-19. Rev Argent Cirug. 2020;112(2): 109-18. [ Links ]

9. Morales AA, Achával M, López Meyer JC, Vega C, Faillace G,Iudica G, et al. Reducción de la exposición en residentes de Cirugía frente al brote de COVID-19. Rev Argent Cirug. 2020;112(2): 105-8. [ Links ]

10. Boyce L, et al. The early response of plastic and reconstructive surgery services to the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2020;73(11): 2063-71. [ Links ]

11. Dorfman R, et al. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Plastic Surgery: Literature Review, Ethical Analysis, and Proposed Guidelines. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;146(4): 482e-493e. [ Links ]

12. Giunta RE, et al. The COVID-19 Pandemic and its Impact on Plastic Surgery in Europe - An ESPRAS Survey. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2020; 52(3): 221-32. [ Links ]

13. Ozturk CN, et al. Plastic Surgery and the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review of Clinical Guidelines. Ann Plast Surg 2020; 85(2S Suppl 2): S155-s160. [ Links ]

14. Pagotto VPF, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on the plastic surgery activity in a high-complexity university hospital in Brazil: the importance of reconstructive plastic surgery during the pandemic. Eur J Plast Surg. 2020: 1-6. [ Links ]

15. Cho DY, et al. The Early Effects of COVID-19 on Plastic Surgery Residency Training: The University of Washington Experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020; 146(2): 447-54. [ Links ]

16. Singh P, et al. The Effects of a Novel Global Pandemic (COVID-19) on a Plastic Surgery Department. Aesthet Surg J. 2020; 40(7): Np423-np425. [ Links ]

17. Díaz A, et al. Elective surgery in the time of COVID-19. Am J Surg. 2020;219(6): 900-2. [ Links ]

18. Shokri T, et al. Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Implications in Craniomaxillofacial Trauma and Head and Neck Reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2020; 85(2S Suppl 2): S166-s170. [ Links ]

19. Mills EC, et al. Telemedicine and the COVID-19 Pandemic: Are We Ready to Go Live? Adv Skin Wound Care. 2020; 33(8): 410-7. [ Links ]

20. Fisher M, et al. The State of Plastic Surgery Education Outside of the Operating Room. Plast Reconstr Surg 2020; 146(5): 1189- 94. [ Links ]

21. Raj S, et al. The COVID-19 Pandemic: Implications for Medical Students and Plastic Surgery Residency Applicants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;146(3): 396e-397e. [ Links ]

22. Dedeilia A, et al. Medical and Surgical Education Challenges and Innovations in the COVID-19 Era: A Systematic Review. In Vivo. 2020;34(3 Suppl): 1603-11. [ Links ]

23. Rose S. Medical Student Education in the Time of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020; 323(21): 2131-2. [ Links ]

24. Chia C, Siah QZ, Stephens M. Potential long-term impacts of surgical placement cancellations. Med Educ Online. 2020;25(1): p. 787309. [ Links ]

25. Fong ZV, et al. Practical Implications of Novel Coronavirus COVID-19 on Hospital Operations, Board Certification, and Medical Education in Surgery in the USA. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24(6): 1232-6. [ Links ]

26. Juprasert JM, et al. Restructuring of a General Surgery Residency Program in an Epicenter of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic: Lessons From New York City. JAMA Surg. 2020; 155(9): 870-5. [ Links ]

27. PLÁSTICA, F.I.D.C. Programa de especialista en Cirugía Plástica. [ Links ]

Received: February 03, 2022; Accepted: April 25, 2022

texto em

texto em