Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista argentina de cirugía

versão impressa ISSN 2250-639Xversão On-line ISSN 2250-639X

Rev. argent. cir. vol.115 no.4 Cap. Fed. dez. 2023 Epub 29-Nov-2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.25132/raac.v115.n4.1743

Original article

Odontogenic deep neck infections

1Sección Cirugía de Cabeza y Cuello. Hospital Central, Mendoza. Argentina

Background:

Patients with deep infections may present with extremely serious and life-threatening conditions. It is unbelievable that someone could die from a molar infection in the 21st century, but it is real.

Objective:

The aim of the present study is to describe the diagnosis and treatment results of a series of patients with odontogenic deep neck infections, and to establish criteria for the management of these infections.

Material and methods:

We conducted a retrospective and descriptive study based on records from a database from September 2006 to June 2022. Only patients with odontogenic deep neck infections were included. The demographic variables, those related to the origin of the complication, the treatment performed, and the patients’ progress were evaluated.

Results:

The sample was made up of 499 patients; mean age was 29 years (12-70) and 288 (57.7%) were men. Late visits and self-medication were recorded in 269 patients (53.9%) and 271 patients (54.3%), respectively. Most of them had not received treatment for the affected tooth at the primary healthcare center. Surgical treatment was performed in 267 cases (53.5%), and the rest were managed with conservative approach. The disease had a favorable course in 497 patients (99.6%) and two patients died of mediastinitis.

Conclusion:

Odontogenic infections should be adequately diagnosed and treated correctly and early to avoid extremely serious complications. Population-based educational campaigns and training for physicians and dentists working in primary care centers and emergency departments could improve this issue.

Keywords: deep neck infections; odontogenic infection; cervical abscess

Introduction

Deep neck infections are a constant concern in emergency departments. There is no standardized approach for the management of these cases and decision-making is sometimes difficult. The lack of oral health care, the tendency to self-medication, the absence of education in prevention and the regional socioeconomic variables are common factors that favor the development of complications. These patients may present with extremely serious and life-threatening conditions1. It is unbelievable that someone could die from a molar infection in the 21st century, but it is real. The aim of the present study was to describe the diagnosis and treatment results of odontogenic infections of the deep neck spaces, and to establish criteria for the early diagnosis and treatment of these infections.

Material and methods

We conducted a retrospective and descriptive study based on records from a database from September 2006 to June 2022. The inclusion criterion was patients with odontogenic deep neck infections requiring hospitalization due to their clinical condition. The presence of one of the following symptoms or greater was considered: impaired general status, fever, neck pain, trismus, submandibular swelling, dysphagia or neck redness. The history of dental pain had to be clear to include patients in the sample.

Patients were excluded if they could be treated on an outpatient basis due to mild intraoral infections or if they had neck infections due to other sources (tonsils, pharynx, or pharyngeal or esophageal perforations due to foreign bodies, among others).

The following variables were evaluated: sex, age, tooth affected, germs involved, time to consultation (early or late), comorbid conditions, self-medication, antibiotics indicated in previous visits, type of treatment and patient progress. Bacterial culture tests were performed randomly or in cases of a torpid course. We analyzed the usefulness of the complementary methods used and the factors that could contribute to the development of this complication.

Results

The sample was made up of 499 patients; 288 (57.7%) were men. Age ranged from 12 to 70 years, with an average of 29 years.

In 437 cases (87.5%) the affected tooth was in the mandible, and in 62 cases (12.5%) in the maxilla. Regarding the timing of patients’ visits to a dentist or physician, 269 patients made late visits (occurring several days after the onset of symptoms), while the remaining visits were made promptly or immediately.

Initially, 271 patients (54.3%) self-medicated, 50.9% of them with amoxicillin. Of those who received professional care, 161 (65.2%) were treated with penicillin and derivatives, but not with β-lactamase inhibitors because these antibiotics are considered inappropriate for that moment of infection. Only 49 patients attended or were referred from peripheral centers (health care centers) where exodontia was performed.

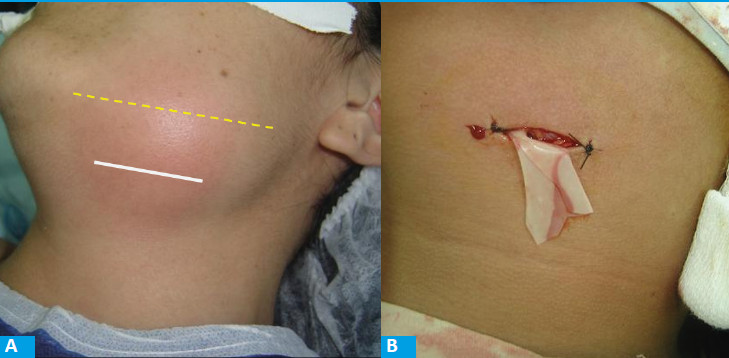

Once the patients were hospitalized, 267 (53.5%) required some type of surgical procedure. In 248 cases, the submandibular space was drained through a 3-4 cm incision made approximately 4 cm (two finger breadths) below the mandible. Tissue was debrided and the mylohyoid muscle was traversed until the floor of the mouth (Fig. 1). In most cases, drainage was performed under local anesthesia.

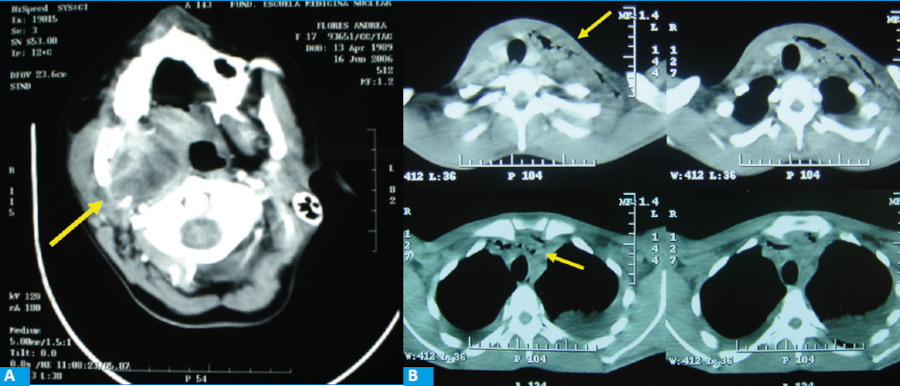

FIGURE 1 Incision for submandibular space drainage. a) Incision site, 4 cm below the mandibular ridge. b) Wound partially closed, with latex sheeting.

The second most common procedure, used in 14 cases, was a wide cervical skin incision, unilateral or bilateral, in which all the affected neck spaces were drained, always reaching the retropharyngeal/ retroesophageal prevertebral space and the superior mediastinum. All the cases were performed under general anesthesia.

Finally, in cases of established mediastinitis, combined surgery was performed with the thoracic surgery team, consisting of a wide cervicotomy with thoracotomy or thoracoscopy in the same operative time. This procedure was performed in 5 cases.

In 174 patients (34.9%), after a collection was ruled out by computed tomography (CT) scan, management included conservative treatment with antibiotics and strict observation, and their condition solved without surgery. Finally, in 58 cases (11.6%), the infection solved after the tooth was extracted and pus drained through the alveolus. This type of intraoral drainage was only performed in mild and very selected cases.

The antibiotic used in all cases was ampicillin/ sulbactam 1.5 g intravenously every 6 hours regardless of the type of strategy used, and when patients were discharged they continued with oral amoxicillin/ clavulanic acid until completing a total of 10 to 14 days of treatment. In all cases, exodontia of the causal element was performed immediately or within the first 12 hours.

When comorbid conditions were evaluated, they were present in only 23 patients, since most of the series was made up of relatively young and healthy people (Table 1).

TABLE 1 Comorbidities in 449 patients with odontogenic deep neck infections

| Comorbidities | n |

|---|---|

| Diabetes | 17 |

| Leukemia | 2 |

| Bone marrow aplasia | 1 |

| HIV | 1 |

| Lupus | 1 |

| RA | 1 |

| TOTAL | 23 |

The disease had a favorable course in 497 patients (99.6%) and two patients died of mediastinitis (0.4%); one was a 20-year-old patient with comorbidities.

Length of hospital stay was quite variable, and patients were discharged when drainage from the wound was minimal, irrigation was no longer required, and patients could manage wound care by themselves.

Discussion

Teeth infections can result in severe and even life-threatening complications, such as intraoral, neck, and subsequent mediastinal infections. Each stage is progressive and is directly related to how early or late the disease is diagnosed and treated. Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial in patients’ outcome2.

The teeth most commonly associated with these infections are the lower molars, and this is directly related to the anatomy of the tooth and the size of its roots, which are close to or below the line of insertion of the mylohyoid muscle3,4, making it easier for the infection to spread to the neck.

In the pre-antibiotic era, pharyngitis and tonsillitis were the main cause of deep neck abscesses. Currently, the most common primary source of deep neck infection is odontogenic1,2,5. The percentages according to the causes (tonsillitis, pharyngeal infection, odontogenic origin, foreign body perforation, etc.) vary in the literature. In our series, 90% of deep neck infections were of odontogenic origin.

In our series, we identified factors that contributed to the development of extensive cellulitis or abscesses. Late consultation and self-medication were patient-related factors, the lack of immediate care in primary health care centers was associated with health policies, and the misuse of antibiotics, delayed exodontia, and in some cases the lack of relevance given to the initial symptoms were factors related to the professional who attended the patient.

Although one tends to think that patients who develop complications from a dental infection have associated comorbidities, in our series, as in most, patients were young1,6,7 and without predisposing factors. Although the presence of comorbidities (e.g., diabetes or leukemia) may complicate the condition, when evaluating patients in the emergency department one should not assume that because they do not have comorbidities, the possibility of extensive infection is unlikely.

According to other authors, deep neck infections are more common in people with lower socioeconomic and cultural levels7,8. This could be attributed to inadequate dental hygiene and reduced inclination towards seeking professional assistance (due to discomfort or prevention). Nutritional status should be considered for research in this group, though it has not been explored in the reviewed literature.

The clinical presentation may vary according to time to consultation. When examining the patient, it is important to take note of signs and symptoms such as neck pain, fever, swelling, skin redness in the neck, raised floor of the mouth and tongue, trismus, tachycardia, tachypnea, odynophagia/dysphagia, and dysphonia. However, we believe patients who present with neck pain, trismus, swelling or edema, should be admitted and require diagnostic work-up before florid signs and symptoms develop. While fever is an important finding, it may be masked by self-medication or previously prescribed medication. The presence of fever and odontalgia is sufficient to order imaging tests. In our opinion, emergency department physicians should utilize this approach for determining which patients require hospitalization and diagnostic work-up.

It should be noted that certain patients with advanced deep neck infections may not exhibit significant clinical symptoms, thereby complicating the diagnosis1.

Mediastinitis is the most dreaded complication, with high mortality rate9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16.

Cervical fascias divide the different compartments through which the infection spreads and may eventually communicate with the thorax. When an infection that originates in the mouth reaches the retropharyngeal/prevertebral space, it creates a pathway, which we call a “toboggan”, that quickly carries the purulent material to the mediastinum. This phenomenon elucidates why, in certain circumstances, the patient’s condition can deteriorate within a few days or even hours.

Other complications as endocarditis, meningitis, or brain abscess, among others, can occur. Although less common, these complications are extremely severe1,2.

Causative organisms for deep neck infections include gram-positive organisms, as Streptococcus viridans, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Staphylococcus aureus, and gram-negative organisms, as Escherichia coli, Klebsiella oxytoca, and Haemophilus influenzae.

Aerobes were found in all patients and anaerobes as Peptostreptococcus and Fusobacterium in 50% of the samples5.

In our study, bacterial culture testing had no effect on the treatment approach or the outcome; however, it is advisable to do such testing if there is a potential risk of a particular strain of bacteria that requires treatment with a specific antibiotic.

Computed tomography scan with intravenous contrast agent is the method of choice and the one that provides more detailed information1,6, as the site and extent of the collection. For this reason, the correct indication is CT scan of the bones of the face (or head), neck and mediastinum with intravenous contrast agent.

In the initial stage of our series, we selected patients for economic reasons, and some cases were correctly diagnosed with ultrasound and puncture without need for CT scan. However, we agree that, if feasible, CT scan should be done in all cases, as it is our current practice. The scan should search for collections as well as the presence of “air bubbles” generated by anaerobic bacteria (Fig. 2).

Once the neck infection has developed, it is crucial to accurately assess the necessary extent of drainage.

Submandibular collections require incision and drainage with placement of drains deep into the mylohyoid muscle.

When the infection has spread, it is necessary to extensively irrigate and drain all the neck compartments involved.

We perform a transverse cervical skin incision that extends beyond the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid (uni or bilaterally), a superior flap up to the proximity of the chin, and an inferior flap up to the suprasternal notch; then, all the compartments determined by the cervical fascias are explored, including the retropharyngeal space and the carotid sheath.

Percutaneous drainage has been suggested by some authors. Others, including ourselves, believe that percutaneous drainage may be useful for small collections and in patients without evidence of major complications6. We clearly prefer open drainage and have not used percutaneous drainage.

There is agreement in the literature that treatment of the affected tooth (in most cases exodontia) should be performed as soon as possible1,5. Along with antibiotics and drainage of the abscess (when appropriate), this constitutes one of the three pillars of treatment. Exodontia results in considerable improvement in patients’ condition. Exodontia can and should be performed even in the presence of infection as long as antibiotic prophylaxis is followed. Local anesthesia has an effect on inflamed tissue despite the longer time it may take to achieve it. Additionally, trismus does not contraindicate extraction as truncal anesthesia partially subsides trismus enough to allow for intraoral surgery.

In our series, all teeth extractions were performed within 24 hours, and most of them within 12 hours.

The type of anesthesia should be carefully selected. In most cases, drainage can be performed under local anesthesia since collections are most commonly located in the submandibular space which is suitable for this procedure. This is consistent with other groups reporting 70% of procedures under local anesthesia and 30% with general anesthesia1. The problem arises when general anesthesia is necessary. In this case, trismus and regional anatomic changes due to inflammation are very important matters that must be considered in order to secure the airway. A fluid communication with the anesthesiologist is mandatory before the procedure. The availability of a video laryngoscopy or fiberoptic bronchoscopy is of utmost importance. Tracheostomy is a matter of debate between different authors9,10. We use it as a last resort as we believe it adds another potential complication to an infected tissue. If a tracheostomy is decided upon, it should be performed at the beginning of the procedure and under local anesthesia. A tracheostomy after attempting orotracheal intubation may cause additional inflammation of hypopharyngeal-laryngeal tissues and is not recommended.

In our series, most patients could be intubated (assisted-orotracheal intubation). Tracheostomy was performed while the patient was awake in one case, while in another case we decided to perform the procedure at the end of the operation due to the anesthesiologist’s concern regarding the risk of extubation. Patients may be transferred to the intensive care unit following surgery with the orotracheal tube. Extubation can occur 24 to 48 hours later once airway parameters indicate it is safe to do so.

In conclusion, deep neck infections should be treated correctly and early and should not be underestimated. Consistent with previous studies2, we observed that time delay is a significant threat to survival. We need to focus on providing populationbased educational campaigns and training for physicians and dentists working in primary health care centers, as well as those working in emergency departments at high-complexity centers.

Finally, we should mention that treatment of odontogenic deep neck infections is based on three simultaneous pillars: antibiotics, surgical drainage if appropriate, and exodontia of the tooth that caused the infection.

Referencias bibliográficas /References

1. Pesis M, Droma E, Ilgiyaev, A, Givol N. Deep Neck Infections Are Life Threatening Infections of Dental Origin: A Presentation and Management of Selected Case. The Isr Med Assoc J. 2019 Dec;21(12):806-811. [ Links ]

2. Zawislak E, Nowak R. Odontogenic Head and Neck Region Infections Requiring Hospitalization: An 18-Month Retrospective Analysis. Hindawi. BioMed Res Int 2021 Jan 18; 2021:7086763. doi: 10.1155/2021/7086763. e-Collection 2021. [ Links ]

3. Manzo Palacios E, Méndez Silva G, Hernández Carrillo GA, Salvatierra Cortéz A, Vázquez MA. Abscesos profundos de cuello. Etiopatogenia y morbimortalidad. Rev Asoc Mex Med Crit y Ter Int 2005; 19(2): 54-59. [ Links ]

4. Jiménez Y, Bagán JV, Murillo J, Poveda R. Infecciones odontogénicas. Complicaciones. Manifestaciones sistémicas. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2004;9 Suppl: S139-47. [ Links ]

5. Rachel H. McDowell; Matthew J. Hyser. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-2022 Sep 19 [ Links ]

6. Pires Brito T, Moreira Hazboun I, Laffitte Fernandes F, Ricci Bento L, Monteiro Zappelini CE, Takahiro Chone C, et al. Deep neck abscesses: study of 101 cases. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2017 May-June; 83(3): 341-8. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2016.04.004. [ Links ]

7. Bidossessi Vodouhe U, Gouda N, Do Santos Zounon A, Beheton R, Lawson Afouda S, Avakoudio F et al. Diffuse Cervico-Facial Cellulitis: Epidemiological, Diagnostic and Therapeutic Aspects at the Teaching Hospital CNHU HKM of Cotonou. Int J Otolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery, 2022, 11, 266-276. DOI: 10.4236/ ijohns.2022.115028 [ Links ]

8. Fusconi M, Greco A, Galli M. Odontogenic phlegmons and abscesses in relation to the financial situation of Italian families. Minerva Stomatol. 2019 Oct;68(5):236-241. [ Links ]

9. Yuan H, Gao R. Infrahyoid involvement may be a high-risk factor in the management of non-odontogenic deep neck infection: Retrospective study. Am J Otolaryngol. Jul-Aug 2018; 39(4): 373-377. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2018.03.009. Epub 2018 Mar 16. [ Links ]

10. Aboul-hosn Centenero S. Celulitis gangrenosa cervical complicada con mediastinitis. Caso clínico. Rev Esp Cirug Oral y Maxilofac vol.25 no.6 Madrid nov./dic. 2003. [ Links ]

11. van Luit R, Jansma J, Schortinghuis J. Neck phlegmon with an odontogenic cause. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2020 Jan 16; 164: D4107. [ Links ]

12. Cortese A, Pantaleo G, Borri A, Amato M, Claudio PP. Necrotizing odontogenic fasciitis of head and neck extending to anterior mediastinum in elderly patients: innovative treatment with a review of the literature. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2017 Feb;29(Suppl 1):159-165. doi: 10.1007/s40520-016-0650-2. Epub 2016 Oct 31. [ Links ]

13. Cárdenas-Malta K, Cortés-Flores Ana, y col. Mediastinitis purulenta en infecciones profundas de cuello. Cir Ciruj 2005;73: 263-267 [ Links ]

14. Luyao Q, Hongyuan X, Xiang L, Xieyi C , Weijie Z , Wentao Q. A Retrospective Cohort Study of Risk Factors for Descending Necrotizing Mediastinitis Caused by Multispace Infection in the Maxillofacial Region. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020 Mar;78(3):386-393. [ Links ]

15. Tian-Guo D, Hong-Bing R, Ying-Kai L. Fatal complications in a patient with severe multi-space infections in the oral and maxillofacial head and neck regions: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2019 Dec 6; 7(23): 4150-4156. [ Links ]

16. Leal de Figueiredo E, Chaves Gama Aires C, De Holanda Vasconcellos R. Persistent Necrotizing Mediastinitis after Dental Extraction. Case Rep Dent. 2019; 2019: 6468348.Published online 2019 Nov 7. doi: 10.1155/2019/6468348 [ Links ]

Received: February 03, 2023; Accepted: August 08, 2023

texto em

texto em