Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista argentina de cirugía

versão impressa ISSN 2250-639Xversão On-line ISSN 2250-639X

Rev. argent. cir. vol.115 no.4 Cap. Fed. dez. 2023 Epub 16-Out-2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.25132/raac.v115.n4.1634

Scientific letter

Rivera’s condom technique for the management of enteroatmospheric fistula

1Servicio Médico Integral. Montevideo, Uruguay

Many devices have been described to collect the effluent from an enteroatmospheric fistula. We can summarize that devices can be manufactured or handmade, expensive or affordable, or vacuum assisted or not. Additionally, they may allow the patient to ambulate or may not assist with postoperative mobility. When facing this condition, several attempts are typically made to obtain a suitable device before discovering the right one for each individual patient. We present the case of a 60-year- old woman with an enteroatmospheric fistula successfully managed using Rivera’s condom technique.

Keywords: enteroatmospheric; condom; Rivera

A postoperative enteroatmospheric fistula is a catastrophic complication for both the patient and the treating team. It is usually caused by a series of surgical complications and poor therapeutic decisions. This is one of the most challenging complications, and the team needs to establish different objectives based on the stage of the fistula. One of the major objectives when treating an enteroatmospheric fistula is to control the bowel effluent and divert it away from the abdominal cavity1. Contact between the bowel effluent and the wound can cause many harmful effects, such as infections due to fecal matter continuously spilling on an open abdomen and skin damage from chemical burns2),(3. For these reasons, it is crucial to adequately control the effluent in the early stages.

We report the case of a patient with an enteroatmospheric fistula. The bowel effluent was controlled using Rivera’s condom technique.

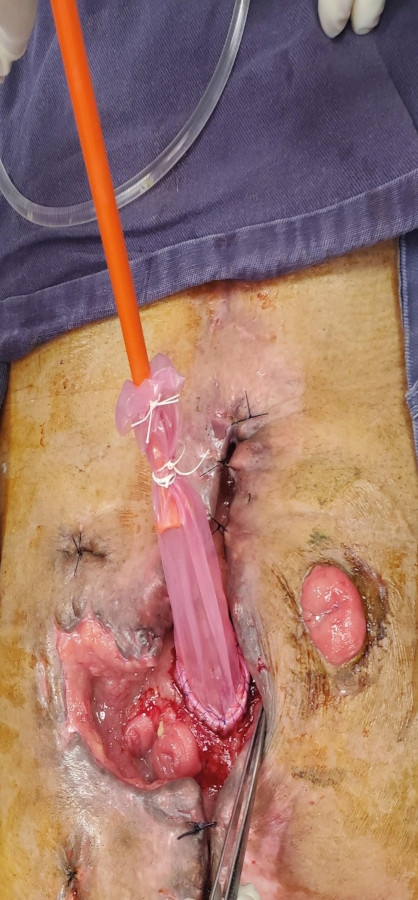

A 60-year-old female patient with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was diagnosed with proximal rectal cancer. Convention anterior resection of the rectum was performed with end-to-end anastomosis. The pathology report showed pT3 N0. On the 11th day after surgery, the medical team detected an anastomotic leak and performed a re-intervention with creation of an end-colostomy. The procedure included resection of a devitalized segment of the small bowel located 40 cm away from the ileocecal valve and side-to-side anastomosis with mechanical stapler. Eight days later, the patient needed another intervention due to failure of the small bowel anastomosis. The procedure included disassembly of the anastomosis and creation of an ileostomy on the right side of the abdomen. The distal end was left abandoned. The patient evolved with stoma retraction that was difficult to manage, in addition to her unwillingness to accept the situation and to recurring dehydration episodes. Nutrition support was started and 1 month after the last surgery, as there was no evidence of infection, she underwent a reoperation to close the ileostomy. On exploration, the local conditions were highly unfavorable. The abdomen was blocked by a mass of adhesions caused by the subacute process, and the bowel loops were friable. A thin loop was sectioned at the level of the distal jejunum and was then hand-sewn. The ileostomy was closed by means of a hand-sewn side-to-side ileo-ceco-anastomosis due to the difficulty in finding the abandoned distal end. Seven days later the patient was re-operated due to anastomotic leak. As the mass of adhesion prevented the creation of a formal ostoma, external drainage was decided to form a controlled fistula. During a month-long period, multiple redo-laparotomies and vacuum-assisted wound closure techniques were necessary. Pezzer probes were used for external drainage with the goal of reducing contamination. As the intestinal ends were located at the bottom of a wound where standard effluent collection devices (pouchs) could not be placed, we used continuous vacuum-assisted devices. These devices managed to keep the patient free of contamination but depended on connection to the wall vacuum system. The output from the fistula was difficult to quantify as it could not be adequately collected, and a substantial amount was lost due to the leaks that occurred throughout the day. Finally, we decided to use the Rivera’s condom technique on the proximal orifice of the fistula for effluent collection. This approach yielded positive outcomes as it prevented contamination and facilitated wound healing (Fig. 1).

This technique allowed for controlled fistula drainage (> 1 L/day), and improved fluid and electrolyte therapy. Additionally, we were able to perform a computed tomography scan and imaging tests of the bowel using contrast agents. This allowed for a better understanding of the anatomy, which in turn helped us to plan the future therapeutic strategy for reconstruction. The patient made slow progress. Intravenous octreotide was prescribed and had a positive effect in reducing output (< 1 L/day) in addition to progress in the establishment of oral feeding with the use of an effective collection device. Parenteral nutrition was not discontinued because oral feeding was not sufficient to fulfill the requirements. The management of bowel effluent also helped the patient in initiating mobilization, following a two-month stay in the intensive care unit, where she was unable to rise. Two months after implementing the technique (4 months following the rectal surgery), the wound was in the process of healing (Fig. 2). During that time, different types of wound care were implemented (dry dressings, moist dressings, and portable vacuum pump, among others), but alginate dressings provided us with the best results. Parenteral nutrition and oral feeding were maintained, octreotide was discontinued and replaced by oral loperamide, and the daily output from the fistula was not > 1 L.

FIGURE 2. Wound before initiating this technique and 2 months later. It almost reaches the skin level.

In our case we performed the technique described by Rivera et al.2 at the bedside without need for extra analgesia or sedation. Over the course of 2 months, we had to replace the condom about 12 times, more frequently at the beginning (every 2-4 days). Once we gained more experience in the technique, each condom lasted an average of 7 days without leakage. Leaks resulted from granulation tissue advancing and loosening the non-absorbable suture material used in the continuous suture. None of the condoms broke because of the contents. Although the anatomy of the intestinal end to which the condom was sutured changed during each replacement, these alterations never impeded repositioning the device or caused significant complications.

Reconstruction surgery was considered six months after the wound healed completely. The imaging tests performed to evaluate the anatomy before reconstruction confirmed the presence of local tumor relapse in the rectal stump and multiple liver metastases. Therefore, surgery was not indicated, and palliative care was initiated.

There are various techniques intended to create an approach for effluent collection, such as placing different types of probes in the intestinal lumen, using floating stomas, and applying continuous vacuum devices. The objective of these techniques is to “buy time” until the patient is ready for definitive reconstructive surgery, ideally 6 months after wound closure. It is essential to note that, in most cases, a combination of these techniques is necessary depending on the stage of the fistula1),(2),(3. Rivera’s condom technique is one of these options2,3, and we successfully employed it to protect the skin from chemical burns, divert and quantify the effluent, and allow ambulation in the presented patient. We believe that this technique is most beneficial in situations where the bowel end is deeply buried in relation with the skin. If the bowel end remains at the level of the skin, we can use devices that attach to the skin, such as colostomy bags.

We believe that Rivera’s condom technique is easily reproducible, inexpensive, can be performed at the patient’s bedside, and should be considered as an option for effluent control in the management of deep enteroatmospheric fistulas that do not allow the use of traditional skin-attached devices.

Referencias bibliográficas /References

1. Saleem A, Farsi A. Unusual techniques in the management of enteroatmospheric fistula. Report of a case. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2020;75: 292-6. [ Links ]

2. Rivera Pérez MA, Quezada González BK, Quiñonez Espinoza M, Almada Valenzuela RR. Manejo de estomas complicados y/o abdomen hostil con la técnica de condón de Rivera. Diez años de experiencia. Cirujano General. 2017; 39(2):82-92. [ Links ]

3. Lillo García C, Oller Navarro I, Lario Pérez S, Fernández Candela A, Sanchez-Guillén L, Díaz Lara CJ, y cols. Manejo de fístula enteroatmosférica compleja mediante la técnica de condón de Rivera como alternativa terapéutica. Cir Esp. 2020; 98 (Espec Congr 1):740. [ Links ]

Received: February 03, 2022; Accepted: June 21, 2022; pub: October 16, 2023

texto em

texto em