Introduction

The objective of this paper is to investigate in terms of stratigraphic unconformities and lithofacies analysis, the record of a Hirnantian condensed sedimentary succession (in the sense of Chan, 1992; Ferreti, 2005; Follmi, 2016), 45 cm thick, represented by the basal strata of the La Chilca Formation in the Talacasto area, at Central Precordillera. Here, Hir-nantian post-glacial deposits are well exposed, and they rest on top of a relatively thick package of open sea carbonate of Lower-Middle Ordovician age, of the San Juan Formation.

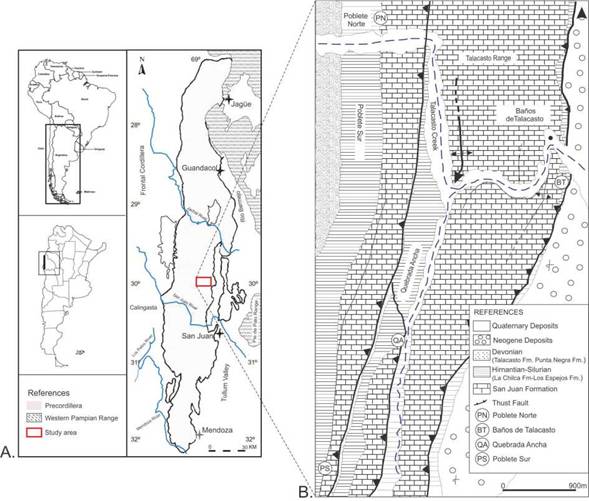

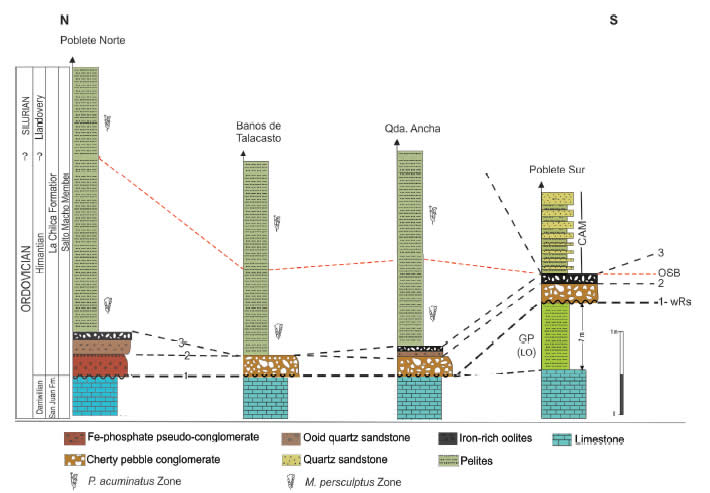

This study focused the stratigraphic, sedimentologic, petrographic, and paleoenvi-ronmental features of the mentioned condensed section, in the following four stratigraphic sections: Los Baños, Quebrada Ancha, Poblete Norte and Poblete Sur (Figure 1A, B). Descriptive lithofacies, transgressive surfaces (unconformities in general sense), and graptolite biozones, combined with EDS analysis (Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy), have been useful tool to support the stratigraphic correlation among the studied sections. In addition, in these four selected sections the Hirnantian succession show a well constrained biostrati-graphic framework, analyzed in the context of the post-glacial Hirnantian transgressive event, but also the tectonic influence of the Tambolar arch has been considered.

Geologic Setting

The Geological Province of Precordillera, Western Argentina, (Figure 1A) (Furque and Cuerda, 1979) is divided into three morpho-structural units: the Eastern Precordillera, characterized as a West-directed thick-skinned fold belt (Ortiz and Zambrano, 1981); the Central Precordillera characterized as an East-directed thin-skinned fold belt (Baldis and Che-bli, 1969; Baldis et al, 1984); and the Western Precordillera which is an East-directed thick fold-belt (Baldis et al., 1984; Ramos, 1999, in Caminos, 1999).

A Cambrian-Middle Ordovician fossilife-rous carbonate bank characterizes the Central and Eastern Precordillera, which is thought as a key for the paleogeographic and geotectonic interpretations of the Precordillera (Ramos et al, 1984; Astini et al, 1995; Baldis et al, 1989; Dalla Salda et al., 1992, Finney et al., 2001, among others) or Cuyania terrane (Ramos et al, 1986). The base of the carbonate bank is unknown as a result of faulting, and to the top is paracon-formably overlain by transgressive siliciclastic and mixed marine deposits of Middle-Upper Ordovician age. An important difference between these morpho-structural units is the wide distribution in the Central Precordillera of the Hirnantian-Silurian succession, represented by shallow water siliciclastic deposits of the Tucu-nuco Group (Cuerda, 1969), and its correlative Tambolar Formation (Peralta et al, 1997). In the Eastern Precordillera these deposits are scarce, only represented by the Don Braulio Formation (Baldis et al, 1982; Peralta, 1993). In the Western Precordillera, Himantian rich-graptolite black shales, have been registered in the Alcaparrosa Formation, close to the Calingasta village (Brussa et al, 1999).

In the Central Precordillera, the Tu-cunuco Group is composed by the La Chilca Formation (Cuerda, 1966) of Hirnantian-early Wenlockian age (Cuerda et al, 1982, 1988; Ker-lleñevich and Cuerda, 1986), and Los Espejos Formation (Cuerda, 1969) of middle Wen-lock-Pridoli according to Benedetto et al, (1992) and García-Muro et al. (2018) or until Lochko-vian in accordance with Mestre et al. (2017). The type section of these units is the Cerro La Chilcato the West of Tucunuco village (Cuerda, 1966). Exposures of these units are recognized along 150 km from the Río Jáchal area (north) to the Río San Juan (south) (Figure 1A), where the Tucunuco Group correlates with the Tam-bolar Formation. (Peralta et al, 1997).

At the northern part of the basin, in the Río Jáchal area, in the Los Blanquitos ridge, La Trampa range, and Cerro La Chil-ca, the basal conglomerate of the La Chilca Formation overlies by disconformity (eroded surface separating parallel strata in the sense of Blackwelder, 1909; Miall, 2016; Kabanov, 2017), Late Ordovician strata. Towards south, at the La Invernada, Talacasto, and La Dehesa ranges, the La Chilca Formation overlies Lower-Middle Ordovician carbonate strata of the San Juan Formation. In addition, in the southern part of the basin, at the Rio San Juan section, the Tambolar and Los Bretes Formations overlie Early Ordovician strata of the San Juan Formation. However, to the East, in the Río Sassito section, the Tambolar Formation overlies Upper Ordovician strata of the Sassito Formation (Astini and Cañas, 1995).

Figure 1: A) Geologic map of the Argentine Precordillera with location of the studied area (After Baldis et al., 1982). B) Stratigraphic and structural features of the Talacasto area (Modified from Baldis et al, 1984). / Figura 1. A) Mapa Geológico de la Precordillera con la ubicación del área de estudio (Modificado de Baldis et al., 1982). B) Características estratigráficasy estructurales del área de Talacasto (Modificado de Baldis et al., 1984).

To the West, at the Sierra de la Invernada, La Chilca Formation correlates with the Los Bretes Formation (Peralta, 2013), in such a way the Tucunuco Group is represented by the Los Bretes Formation and the overlaying Los Espejos Formation (Peralta, 2013). The base of the La Chilca Formation and its correlatives, is characterized by a chert pebble conglomerate level of variable thickness, no more than 30 cm (Rolleri, 1947; Marchese, 1972; Peralta, 1990).

Methodology

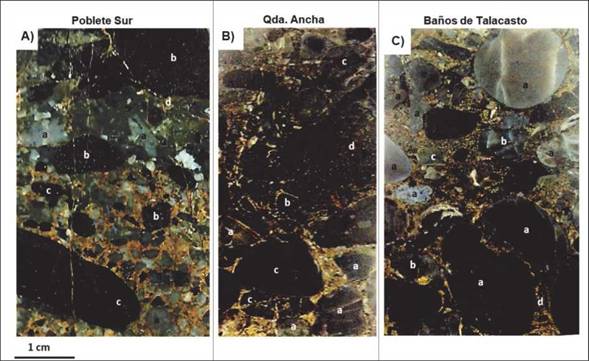

In the Baños de Talacasto, Quebrada Ancha and Poblete Sur sections (Figure 1B), the basal conglomerate is well exposed and preserved, and it was analyzed to a centimeter scale. However, in the Poblete Norte section the conglomerate is not registered, and a phosphate pseudo conglomerate level occurs at the base of the La Chilca Formation. In each of these sections, lithology, thickness, lithological composition, sedimentary structures, fabric, texture, geometry, vertical and lateral lithofacies relationship, and fossil content, are described, in order to determine facies and depositional environments. Nine polished samples and thin sections were analyzed to determine texture, grain morphology and composition, in addition to fossil remains, sedimentary structures and fabric.

Following the Tucker (2003) methodology, in a 1x1m grid, 94 clasts granule to pebble size were sampled from the conglomerate, according to Udden-Wentworth scale (in Wentworth, 1922); 31 from the Poblete Sur, 33 from the Quebrada Ancha, and 30 from the Baños de Talacasto. Descriptive and multivariate statistical analyses were performed, using the free software InfoStat and SPSS. The patterns found were analyzed considering roundness and sphericity in accordance with Zingg (1935); Powers (1982); Scasso and Limarino (1997) classifications.

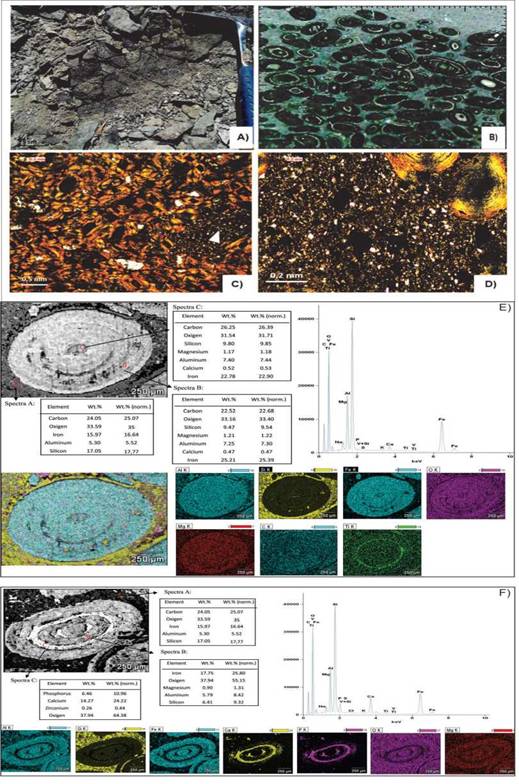

In each of the ferriferous and Fe-phos-phate levels, values of thickness, geometry, lateral extension, composition and texture, as well as their stratigraphic relationships, were considered. The petrographic studies were performed in thin and polished sections, and the descriptions of the ooids and their structures were based on the methodology of Flügel (2010). Analysis of Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) in oolitic ironstones were carried out at the Argentine Institute of Nivo-logy, Glaciology and Environmental Sciences (IANIGLA), in order to characterize the composition and morphology of the ooids.

The sedimentological and stratigraphic data obtained, are the result of petrographic, geochemical (EDS), and paleobiologic integrated studies, in accordance with similar methodology applied in Paleozoic ironstone of Gondwana (Van Houten, 1985; Bayer, 1989; Young, 1989b; 1992; Ferrati, 2005; Oggiano and Mameli, 2006; Rahiminejada and Zand-Moghadamb, 2018). To characterize the unconformities recorded in the 45 cm thick of the Hirnantian stratigraphic sections, we follow the Blackwelder, (1909); Dunbar and Rogers (1957); Miall, (2016); Kabanov (2017) classifications.

Stratigraphic DescriptionIn the Talacasto area (Figure 1B), the Early Paleozoic succession starts with Lower-Middle Ordovician limestone of the San Juan Formation (Cycle I, Beresi, 1991), whose basal levels are not exposed as a result of the Andean thrust, and at the top is paraconformably overlain by the La Chilca Formation. In the Quebrada Ancha section, the late unit was divided into two members (Baldis et al, 1984); the lower Salto Macho Member (Hirnantian-Llandovery), and the upper Cuarcitas Azules Member (Wenlock), whose ages are based on graptolites (Cuerda et a/., 1988; Albanesi et al., 2006; Lopez et al., 2020) and palynomorphs (García-Muro and Rubinstein, 2015) assemblages.

It is emphasized that in all performed sections, at the base of the Salto Macho Member a conspicuous wave ravinement surface (wRs) (in the sense of Cattaneo and Steel, 2003; Zec-chin et al., 2019), is recognized as a result of the Hirnantian transgressive event, whether onto the Lower-Middle Ordovician San Juan Formation (Los Baños, Quebrada Ancha, and Poblete Norte sections), or above of an Upper Ordovician pelite succession no more than 7 m thick as in the Poblete Sur section.

In the Talacasto area, the basal conglomerate of the La Chilca Formation has been named as the Ta/acasto conglomerate or Si/urian basa/ conglomerate (Rolleri, 1947), but also as the basa/ conglomerate of the Tucunuco Group (Cuerda, 1969). Studies on the origin of the conglomerate, as a result of the post-glacial transgressive Hirnan-tian event, have been carried out in the Cerro La Chilca (Astini and Benedetto, 1992), Las Agua-ditas section (Astini and Piovano, 1992), and Poblete Norte and Quebrada Ancha sections in the Talacasto area (Asurmendi et al., 2017, 2018). An extensional model for the tecto-sedimentary evolution of the Hirnantian-Silurian succession of the Tucunuco Group and its correlatives, has been suggested by Peralta (2006).

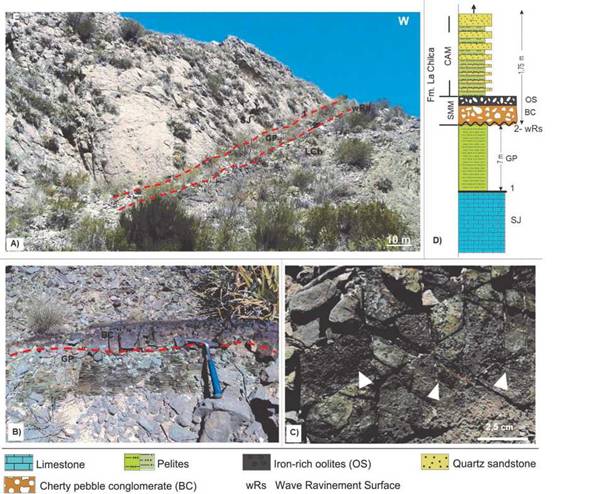

Baños de Talacasto SectionIn this section, the Hirnantian succession starts with the basal conglomerate of the La Chilca Formation, 30cm thick, which overlies by disconformity (wRs) (in the sense of Blac-kwelder, 1909; Cattaneo and Steel, 2003) limestone of the San Juan Formation (Figure 2A). The conglomerate is overlain, in sharp contact, by laminated rich-graptolite pelites of the Salto Macho Member, bearing the Hirnantian Meta-bo/ograptus perscu/ptus Zone, the Rhuddanian Pa-rakidograptus acuminatus and Atavograptus atavus Zones, indicating the Hirnantian-Rhuddanian boundary (Cuerda et al., 1988; Lenz et al., 2003). It is to be noted in this section, at the base of the Salto Macho Member, the absence of oolitic and ferruginous levels, which occur in the Poblete Norte and Sur, and Quebrada Ancha sections (Figure 2B).

Quebrada Ancha SectionIn the same way as in the previous section, herein, the basal conglomerate, 25 cm thick, erosively (wRs) overlies limestone of the San Juan Formation (Figure 3A). At the top, the conglomerate is overlain, sharp contact, by a ferruginous oolitic sandstone level (Figure 3A), 12 cm thick, paraconformably covered by 5m thick of rich-graptolite pelites bearing the Hirnan-tian-Rhuddanian boundary (Cuerda et al, 1988) (Figure 3A). Up section, this member gradually pass into the fine-grained siliciclastic succession of the upper Cuarcitas Azules Member.

Figure 2: A) Baños de Talacasto section. 1- Erosional contact, wave ravinement surface (wRs) (dashed line) between the San Juan Fm. limestone (SJ), and the basal conglomerate of the La Chilca Formation (BC, lithofacies A1). B) Stratigraphic column of the Salto Macho Member. Oolite deposits are absent. / Figura 2. A) Sección Baños de Talacasto. 1- Contacto erosivo (líneapunteada) entre las calizas de la Formación San Juan (SJ) y el conglomerado basal de la Formación La Chilca (BC, litofacies A1). B) Columna estratigráfica del Miembro Salto Macho. Los depósitos oolíticos se encuentran ausentes.

Poblete Sur SectionIn this section, a greenish to greyish laminated pelites succession 7 m thick, erosively overlies the San Juan Formation, and in turn is erosively (wRs) overlain by the basal conglomerate of the La Chilca Formation (Figure 4A, B, D), 20 cm thick. On the basis of its stratigraphic position, and its probable lithostratigra-phic correlation with the upper part of the La Cantera Formation in Don Braulio section, at Villicum range, an Upper Ordovician age is suggested for this pelites succession. It is to be noted that in this section, the wave ravinement surface (wRs), has been developed onto de Ordovician pelites succession, at the base of the chert pebble conglomerate.

The basal conglomerate is covered in sharp contact, by a black ferruginous oolitic level, 5-7 cm thick (Figure 4C). In this section the rich-graptolite pelites of the Salto Macho Member are absent, whence the oolitic level is overlain by the upper Cuarcitas Azules Member (Figure 4D).

Poblete Norte SectionIn this section the basal conglomerate is not recognized (Figure 5A), and a ferruginous reddish pseudo-conglomerate level, ca 33cm thick, occurs at the base of the Salto Macho Member of the La Chilca Formation, overlaying limestone of the San Juan Formation. The Fe- phosphate level is paraconformably covered by 10 cm thick of pelites, with ooids, passing to Fe-phosphate oolites, overlain in sharp contact, by rich-graptolite pelites and very fine-grained sandstone beds, bearing de Hirnantian-Rhudda-nian boundary (López et al., 2018, 2020). This succession is in sharp contact overlain by quartz sandstone thick beds of the Cuarcitas Azules Member (Figure 5B). Evidence of glaciogenic features have not been recognized in this section, in the basal levels of the La Chilca Formation, as mentioned by Asurmendi et al. (2017; 2018).

Figure 3: A) Basal strata of the La Chilca Formation, at the Quebrada Ancha section. The dashed line indicates the contact between the referenced levels. 1- Erosional surface (wRs) between the San Juan Fm. (SJ) and the basal conglomerate of the La Chilca Fm. (BC, lithofacies A1). 2- Sharp contact between the basal conglomerate and the overlaying oolitic sandstone (OS, lithofacies B). 3- Sharp contact between the oolitic sandstone (OS) and fossiliferous pelites. B) Stratigraphic column of the Salto Macho Member. References same as in A. / Figura 3. A) Estratos basales de la Formación La Chilca en la sección de Quebrada Ancha. La línea punteada indica el contacto entre los niveles referenciados. 1- Paraconcordancia, superficie erosiva (wRs), entre la Formación San Juan (SJ)y el conglomerado basal de la Formación La Chilca (BC, litofacies A1). 2-Contacto neto entre el conglomerado basal y las areniscas oolíticas (OS, litofacies B) suprayacentes. 3- Contacto neto entre el nivel de oolitas (OS) y las pelitas fosilíferas del Miembro Salto Macho. B) Columna estratigráfica del Miembro Salto Macho.

Description of Lithofacies

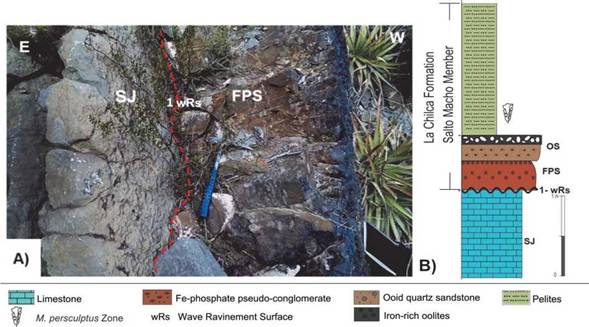

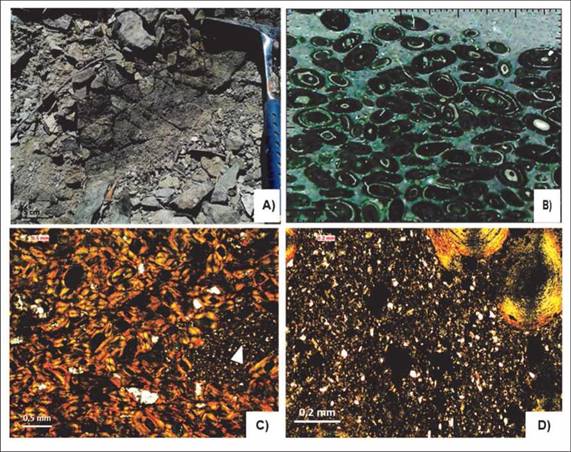

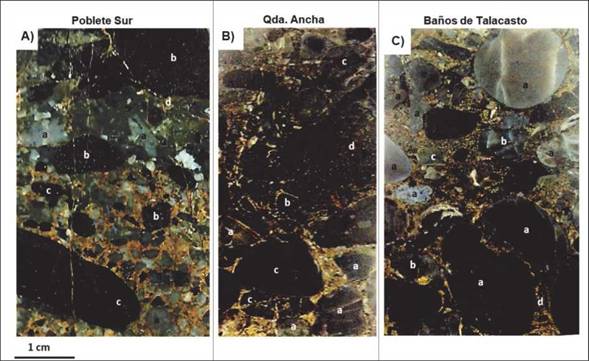

Lithofacies A1: Cherty pebble conglomerateThis lithofacies is represented by the basal conglomerate which is well exposed in the Los Baños, Quebrada Ancha and Poblete Sur sections. The conglomerate is variable in thickness, 20 to 30 cm, with tabular geometry. Basically consist of oligomictic granule conglomerate, clast to matrix supported, more than 75% of siliceous components (chert, chalcedony, and monocrystalline quartz), with predominance of dark chert clasts, 20% of limestone, and 5% organic fragments (Figure 7A-C).

Siliceous clasts are rounded to well rounded, and show high sphericity (Figure 6A-C); chert and chalcedony are dolomitized and exhibit iron oxide patina and quartz-filled microfractures. Limestone clasts are smaller, with sub-angular to sub-rounded edges, and low sphericity (Figure 6B). Organic fragments are scarce and exhibit iron oxides alteration, although some fragments of valves are recognized. The matrix is sandy and polymictic, with a yellowish-gray coloration, composed of monocrystalline and polycrystalline quartz and fine-grained fragments of limestone (Figure 8A). Cement is calcareous, with primary reddish to dark reddish colored micrite remains, suggesting the presence of iron oxides and hydroxides (limonite) (Figure 8B, C).

Figure 4: A) Panoramic view to the south of the Poblete Sur section; the dashed lines indicate paraconcordances; 1-between Middle-Upper Ordovician greenish pelites (GP) and San Juan Formation. (SJ); 2- between GP and La Chilca Fm. (wRs). B) Close-up of the erosional contact (red dashed line), between greenish pelites (GP) and the basal conglomerate (BC, lithofacies A1). C) Oolitic sandstone bed (OS, lithofacies B) overlying the basal conglomerate; the white arrows indicate oolite concentration. D) Stratigraphic column; SJ, San Juan Formation, SMM, Salto Macho Member, and CAM Cuarcitas Azules Member. / Figura 4. A) Vista hacia el sur de la sección Poblete Sur. Las líneas de trazo rojo indican paraconcordancia, 1- entre pelitas verdes (GP) del Ordovícico Medio-Superior y la Formación San Juan (SJ), 2- entre GP y la Formación La Chilca (wRs). B) Detalle del contacto erosivo (trazo rojo), entre las pelitas verdes (GP) y el conglomerado basal (BC). C) Nivel oolítico (OS) que sobreyace al conglomerado basal; las flechas blancas indican sectores de concentración de oolitas. D) Columna estratigráfica; SJ, Formación San Juan, miembros Salto Macho (SMM) y Cuarcitas Azules (CAM).

In the Baños de Talacasto section, the conglomerate shows two main detrital populations of siliceous components: granule and pebble. The clasts exhibit poor sorting, high roundness and high sphericity, while limestone clasts show sub-roundness and low sphericity.

In the Quebrada Ancha section, the average size of siliceous clasts is granule to pebble, moderately to poorly sorted, prevailing rounded shapes with a low sphericity. Lithic components (limestone) and matrix fragments exhibit moderate roundness and low to high sphericity. Chert and limestone clasts prevail in its composition; at the base the clasts are oriented, and towards the top the internal structure become massive (Figure 6A). The clasts size range from regular to well sorted granule to fine-grained pebble (2-8cm) (Figures 7A, C, D). The micrite matrix occurs at the basal level of the conglomerate (Figure 8D).

Figure 5: A) Poblete Norte section, picture shows the erosional contact (dashed line) between San Juan Fm. (SJ) and Fe-phosphate pseudo-conglomerate (FPS, lithofacies A2), capped by oolite sandstone (OS, lithofacies B) at the base of the La Chilca Formation. B) Stratigraphic column; References same as in A. / Figura 5. A) Sección Poblete Norte, mostrando el contacto erosivo (trazo rojo) entre la Formación San Juan (SJ) y el pseudo-conglomerado Fe-fosfático (FPS), cubierto por arenisca oolítica (OS) en la base de la Formación La Chilca. B) Perfil estratigráfico de la sección Poblete Norte.

In the Poblete Sur section, the basal conglomerate presents a matrix-support structure at the base and clast-support at the top (Figure 6A). In this section, organic fragments are scarce, and clasts of chert and limestone predominate. At the base of the basal conglomerate, the clasts are oriented, and toward the tope this structure disappears becoming massive. (Figure 6A).

Paleoenvironmental interpretation of lithofacies A1The textural maturity, fabric, and matrix nature indicate that the conglomerate evolved in a storm-dominated environment, such as is suggested by previous authors toother sections of Precordillera (Astini and Piovano 1992; Astini and Benedetto 1992). The clasts are well rounded to sub-rounded, and exhibit high sphericity, as a result of their constant reworking along the beach, and their distribution depend of the wave energy and the morphology of the basin (Clifton, 2003).

Lithological and textural analysis of the clasts suggests provenance from the San Juan Formation (Marchese, 1972; Cuerda et al, 1988), and the presence of polycrystalline quartz in the matrix, suggest a low degree metamorphic area as a secondary source (Tortosa et al, 1988).

Lithofacies A2: Fe-phosphate pseudo-conglomerateIs only recognized in the Poblete Norte section; is represented by a pseudo-conglomerate level, 33 cm thick, and tabular geometry, which overlies in disconformity (paraconcordance) to the San Juan Formation. It is composed of a ferruginous reddish matrix-supported sandstone level, with Fe-phosphate nodules, up to 5cm diameter, and scattered cherty pebbly clasts. The carbonate content is high at the base of the level, and decreases towards the top.

The middle and upper part is yellowish to reddish brown, which suggests the presence of iron and phosphate in the matrix. Towards the top a marked increase in the Fe-phosphate nodules population and chert clast is observed (Figure 5). The chert clasts and matrix components present similar characteristics to those of the Baños de Talacasto, Quebrada Ancha and Poblete Sur sections.

Paleoenvironmental interpretation of li-thofacies A2The presence of phosphate nodules in lithofacies A2 suggests a low energy environment, as the apatite precipitation may have been favored by the development of anoxic conditions (Frakes and Bolton, 1984; Siy, 1988). A different scenario suggests the phosphate-enriched nodules, internally homogeneous in composition, probably replaced precursors of calcite nodules under suboxic conditions (Marshall-Neil and Ruffell, 2004). The chert clasts and sandy matrix textural features, suggest reworking of the pre-existing deposits during the early stages of active wave action near of the coast (Baraboshkin, 2008). Phosphate nodules and chert clasts accumulation would be a result of a progressive decrease in energy as well also by the low sedimentation rate in the upper part of this lithofacies. Lithological analysis suggest that the chert and the Fe- phosphate sandy matrix are likely to come from the same sources that the lithofacies A1.

Lithofacies B: Oolitic sandstoneThis lithofacies is well exposed in the Quebrada Ancha, Poblete Sur and Poblete Norte sections, but is absent in the Los Baños de Talacasto. It is represented by a tabular bed of ca 15 cm thick, composed of brownish quartz sandstone with chamosite ooids and reverse grading, capped by an oolitic level 1-3cm thick. This facies is divided into two subfacies:Subfacies B1, Ooid quartz sandstone

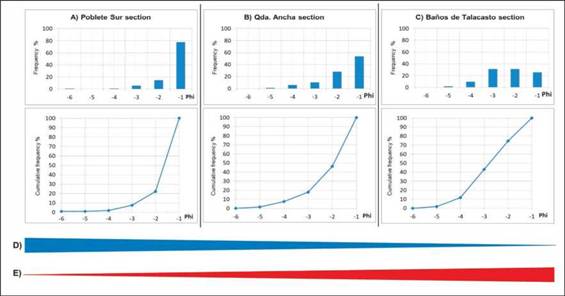

Figure 7: Histograms of comparative and cumulative frequency of all samples A) Poblete Sur, N=31; B) Quebrada Ancha, N=33; C) Baños de Talacasto, N=30. Histograms of frequency show distribution for sections in A) and B), and a bimodal distribution in C). Cumulative frequency curve, shows the distribution of coarse elements to the left, and finer to the right, for each section. C) and d) show the variations of the textural parameters analyzed: sorting, matrix content, roundness and sphericity. D) Decreasing pattern of sorting and matrix content, from Poblete Sur to Baños de Talacasto sections. | Shows a notorious increasing in asymmetry (in accordance with cumulative frequency histogram), and roundness and sphericity (in accordance with Zingg, 1935; Powers, 1982). / Figura 7. Histogramas de frecuencia y frecuencia acumulada, para un total de N=94 clastos tomados del conglomerado basal, distribuidos de la siguiente forma: A) Poblete Sur, N=31, B) Quebrada Ancha, N=33; C) Baños de Talacasto, N=30. Los histogramas de frecuencia muestran una distribución para las secciones en A) y B), y una distribución bimodal en C). Curva de frecuencia acumulada, muestra la distribución de elementos gruesos a la izquierda y más finos a la derecha para cada sección. C) y D) muestran las variaciones de los parámetros texturales analizados: selección, contenido de matriz redondezy efericidad. D) Patrón decreciente de selección y contenido de matriz desde los tramos de Poblete Sur hasta Baños de Talacasto. E) Se muestra un notorio aumento de la asimetría (de acuerdo con el histograma de frecuencias acumuladas), y de la redondezy la esfericidad (de acuerdo con Zingg, 1935; Powers, 1982).

It consist of a grain-supported oolitic sandstone, composed of dark chamosite ooids and scattered, sub-angular to sub-rounded siliceous clasts (chert, chalcedony, and mono-crystalline quartz) (Figure 9B, C). In minor proportion calcareous and lithic fragments are present. The ferruginous limonite detrital matrix prevails, although dark micrite also occurs in pseudo-flasher or lenticular structure (Figure

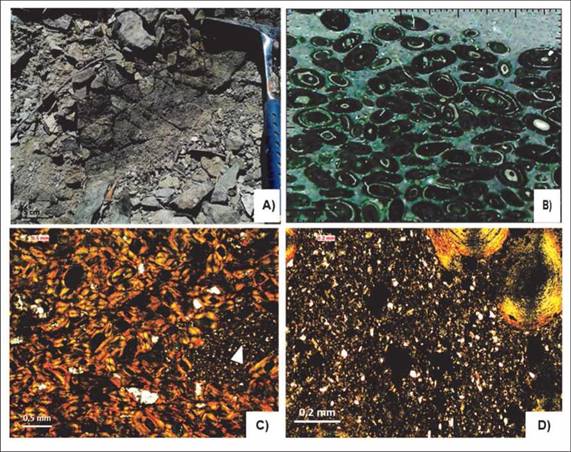

Subfacies B2, Iron-rich oolitesIt is composed of clast-supported dark grey to black ferruginous oolitic level (Figure 10A). According to EDS analysis and petrography, the ooids are mostly made of chamosite and, in a minor proportion, of rounded to ellipsoidal phosphate, ranging from 0.5 to 1mm, exhibiting coeval deformation (Figure 10B, E, F). The nuclei are mostly composed of silica, phosphate, and siderite grains, heavy minerals and, to a les ser extent, organic grains, consistent with EDS analyzes (Figure 10C, E, F). Concentric ooids predominate over superficial, regenerated, and composite ooids, according to Flügel (2010) classification. Ooids lie in contact with each other, and the siliceous detrital matrix infill interstices just like the previous subfacies (Figure 10D).Paleoenvironmental interpretation of li-thofacies B

The textural characteristics of the ooids indicates a hydrodynamically active environment, related to a coastal setting during a period of low rate of sedimentation. The ellipsoidal shapes of the ooids may be the result of predominance of coastal drift, as part of a sin-sedimentary process (Dabrio, 2010). In the oolitic sandstone li-thofacies, reworking features or allochthonous ooids have not been observed. The chamosite ooids and the presence of chert, chalcedony, and limestone, suggest an in situ deposition, probably in a chamositic platform (Brookfield, 1971), with very rugged shoreline and pene-plained mountainous relief (Young, 1989 b; 1992). Similar deposits and paleoenvironment have been described in the Silurian Lipeon Formation, in the North West Basin of Argentina (NOA) (Bossi and Viramonte, 1975).

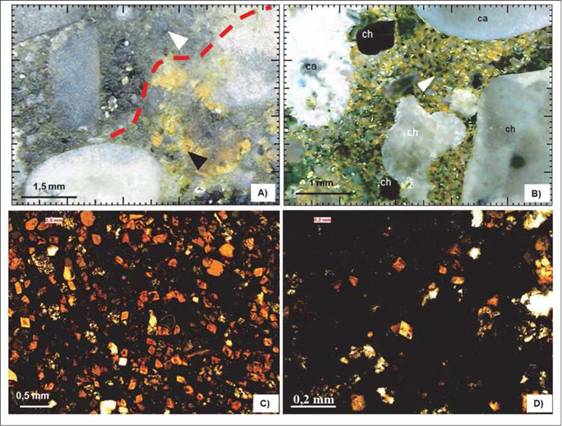

Figure 8: Thin sections from the basal conglomerate of the Baños de Talacasto. A) Dashed line indicates the contact between the detrital matrix (white arrow) and the oxidized detrital matrix B) Detail of a, showing ferruginous detrital matrix and chert (ch) and chalcedony (ca) grains, embedded in the matrix. C) Detail of b (white arrow), polymictic matrix sand-sized. D) Detail of the matrix in C, A high degree of oxidation is observed in the components of the conglomerate matrix. / Figura 8. Secciones delgadas del conglomerado basal en Baños de Talacasto. A) Contacto (línea de trazo rojo) entre la matriz detrítica (flecha blanca) y la matriz detrítica oxidada (flecha negra). B) Detalle de A, mostrando la matriz detrítica ferruginosa (flecha negra en A), y granos de chert (ch) y calcedonia (ca) flotando en la matrix (flecha blanca). C) Detalle de B (flecha blanca), matrizpolimíctica tamaño arena. D) Detalle de la matriz en C, se observa un alto grado de oxidación en los componentes de la matriz del conglomerado.

Figure 9 Polished samples from the Quebrada Ancha section. A) Oolitic sandstone lithofacies; B) Highlighted with red line the pseudo-flasher/lenticular structure not outlined in A. C) Detrital matrix composed of dark grains of chert (ch), whitish quartz (C), enriched in light brown limonite (L). D) Chamosite ooids (o), in a gray micritic matrix (top of subfacies B). / Figura 9. A) Tope mvelooMoo, sección de Poblete Sur. B) Pulidos correspondientes a la sección de Quebrada Ancha. A) Litofacies de arenisca ooMca; B) Se destaca con líneas de trazo rojo la estructura pseuáoflbserlknicular no delineadas en A. C) Matrig detrítica, compuesta de granos oscuros de chert (ch), cuarzo blanquecino (c),y enriquecida en limonitapendo clero (L). D) Ooides chamosíticos de coloración oscura (o) en una meting núcríica gris (tope de subfacies B)

In this case, iron hydroxides and bicarbonates, derived from the mainland, react with the argillaceous sediment in an anoxic environment, producing chamosite. Bayer (1989) suggests that the primary minerals were carbonate, replaced by iron compounds, in a shallow shelf environment. There, the hematite or chamosite formed in situ or near of depositional environment are present. The release and rework of the chert could give way to the generation of iron oxides and hydroxides (Bayer, 1989), as observed in the matrix of the basal conglomerate of the La Chilca Formation (lithofacies A1), and also in the oolitic sandstone (lithofacies B). In the Talacasto area decomposition of the iron nodules present in the San Juan Formation limestone, is considered as a secondary source (Beresi, 1986).

The characteristics of this lithofacies suggest nearshore to shoreface setting. The litho-facies variations are evidenced by the increase in the Fe content from subfacies B1 to B2, but also by the modification of matrix and fabric in the oolitic sandstone lithofacies. These deposits would have originated in mild moist tropical to subtropical climates (Van Houten, 1985; Young, 1989a), in coastal marine environment, as proposed to Lipeon Formation by Bossi and Viramonte (1975). Oolitic deposits in temperate climates have been recorded at high latitudes, in similar sedimentary conditions in the Ordo-vician-Silurian transition registered in Austria and Italy (Ferrati, 2005; Oggiano and Mameli, 2006). The Ferich sediment is transported from temperate to cold seas, and then, the concentration, dissolution and subsequent precipitation processes occur during the transgression (Bayer, 1989; Astini 1992).

Figure 10: A) Top of oolitic level in Poblete Sur section. B) Alternation of chamosite ooids (black) with phosphate (white) bands in Poblete Sur section. C) Quebrada Ancha section. Deformed ooids by compaction exhibit parallel orientation to layering. The matrix is detrital (white arrow) D) Detail of the siliceous detrital matrix (white arrow in C), ooids-bearing quartz sandstone subfacies. E) EDS diagrams of elements composition of concentric ferruginous ooids, and concentric Fe-phos-phate ooids (F)from the Talacasto area. / Figura 10. A) Tope nivel oolítico, sección de Poblete Sur. B) Ooides chamosíticos con alternancia de bandasflogóticas presentes en ¡a misma sección. C) Sección de Quebrada Ancha, ooides con deformación, compactación, y orientación paralela a la estratificación La matriz es detrítica (flecha blanca). D) Detalle de la matriz detrítica silícea (Flecha blanca en C), subfacies de arenisca cuarzosa con ooides. E) Diagramas EDS de los ooides concéntricos ferruginosos y ooides concéntricos Fe-fosfáticos (F) en el área de Talacasto.

In the Precordillera, during the Late Ordovician glacial and post-glacial events, ironstones could be linked to cold or temperate climate, as a result of the paleolatitudinal position (30 ° and 45 ° L.S) (Van Houten, 1985;Astini, 1992; Ferrati, 2005). In the Gondwana platforms, at middle to high latitudes, the iron provenance occurs as a result of the weathering of Fe-rich rocks exposed during the regression (Oggiano and Mameli, 2006).

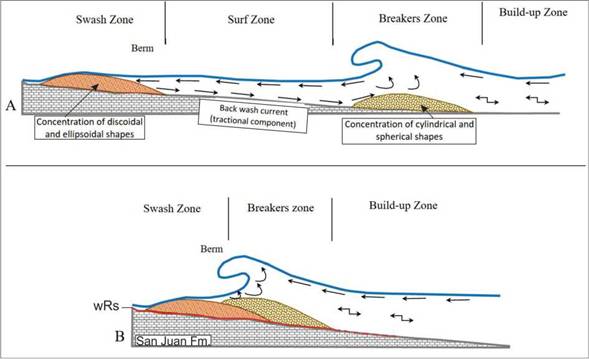

Figure 11: A) Integrated beach model considering the textural characteristics of the clasts in each of the zones. B) Sketch showing the process on a gravel beach, without a transition zone. The basal conglomerate (Lithofacies A1 in this paper), would be the result of these kind accumulations. (Modified from Arche, 1992 and Spalletti, 2007). / Figura 11. A) Modelo de playa integrado considerando las características texturales de los clastos en cada una de las gonas. B) Croquis que muestra elproceso en una playa de grava, sin gona de transición. El conglomerado basal (Litofacies A1 en este trabajo), sería el resultado de este tipo de acumulaciones. (Modificado de Arche, 1992y Spalletti, 2007).

Discussion

Some considerations about the basal conglomerate of the La Chilca Formation.

In the Baños de Talacasto and Quebrada Ancha sections, the basal conglomerate of the

La Chilca Formation, overlies erosively carbonate strata of different lithofacies and age of the Early Ordovician San Juan Formation (Bal-dis and Beresi, 1981; Beresi, 1986, 1991; Soria et al, 2013). However, in the Poblete Sur section Upper Ordovician pelite succession overlies the San Juan Formation. The Hirnantian age of the conglomerate, is well constrained on the base of the M. persculptus Biozone record (Cuerda et al., 1988; Lenz et al., 2003; López et al, 2018). In the Las Aguaditas section (Astini and Piovano, 1992), and the Cerro La Chilca section (Astini and Benedetto, 1992), the lower part of the La Chilca Formation, is characterized as inner shelf deposits. Nevertheless, in the Talacasto area, a siliciclastic ramp environment is suggested by Asurmendi etal. (2017, 2018).

The conglomerate is considered as a result of the Hirnantian post-glacial transgressive event (Astini and Piovano 1992; Peralta 2006, 2007; Benedetto and Cocks, 2009), evolved in shoreface environment (Astini and Piovano 1992; Astini and Benedetto 1992), with sediment redistribution by wave and storm action (Astini and Maretto, 1996). In the Talacasto area, lithology and fabric of the basal conglomerate suggest development in a transgressive gravel beach with more than one breaking zone, characterized by the accumulation of coarse deposits and by deficiency or absence of sandy deposits (Arche, 2010) (Figure 11A). This may be attributed to the basin morphology during a rapid postglacial sea-level rise, which could have modified the path of the sediments before reaching the coast (Postma and Nemec, 1990).

Figure 12: Litho and biostratigraphic correlation of the basal strata of the La Chilca Fm., between the four sections studied. References same as in figures 2, 3, 4, 5. wRs, wave Ravinement surface. OSB Ordovician-Silurian Boundary.Figura 12. Correlación litoestratigráfica y bioestratigráfica de los estratos basales de la Fm La Chilca, entre las cuatro secciones estudiadas. Referencias iguales a las de las figuras 2, 3, 4, 5. wRs, superficie de barranco de olas. OSB Límite Ordovícico-Silúrico.

The deficiency or absence of sandy facies associated with the conglomerate, suggests the beach environment did not develop a transition zone. According to Clifton (2003), as the shore-face lacks sand, then the conglomerate consists of a thin layered gravel bed, widely extended on the coastal zone. As sea level rises the conglomerate moves towards the coast, and remains as a transgressive lag above the erosive surface (Clifton, 1981, 2003; Siggerud et al., 2000), in which spherical shapes predominate (Bluck, 1999).

Due to the uplift of the Tambolar Arch and the rapid Hirnantian post-glacial transgression, the beach does not consolidate and the accommodation space is vertically reduced to a thin conglomerate deposit, no more than 30 cm thick, extended along the Central Precordillera following the lag model proposed by Yang (2007).

We suggest that in the Talacasto area, the transgressive basal conglomerate would be the result of two depositional events (Figure 11B). The first one, produced in the breaking zone, a basal level, 10 to 15 cm in thickness, related to the berm deposit, onto the San Juan Formation, as in the Poblete Sur section (Figure 6A). The second produced a thin layered gravel deposit, 10-15 cm thick, on the top of the berm as in the Baños de Talacasto section (Figure 6C), which spread out along the coastal zone. Additionally, both conglomerate levels occur in the Quebrada Ancha section. Similar models and process for Paleozoic deposits have been described by Clifton (2003), Myrow et al (2004) and Spalleti (2007).

In accordance with the obtained data, the lithofacies A2 would represent a phosphate lag and stratigraphic equivalent of the lithofa-cies A1. Compositional and textural analysis of Lithofacies A2, suggest reworking of pre-existing regressive deposits, during a maximum regional transgression episode that produced the phosphate lag, as a result of condensation process (Simandi et al., 2012). Condensed sections similar to Lithofacies A2, have been registered in the Early-Middle Ordovician ramp from the Russian Plate (Zaitsev and Barabos-hkin, 2006), and in the Lower Valanginian and basal Upper Valanginian from the South West Crimea (Baraboshkin et al., 2002). According to Gómez and Fernández (1992) and Baraboshkin (2008), the condensation would be linked to deep shelf environment during the stages of maximum transgression.

The erosional surface at the base of the conglomerate (Lithofacies A1) and stratigraphic equivalent (Lithofacies A2), may be considered as a wave ravinement surface (wRs) (Cattaneo and Steel, 2003), developed during the first stage of the transgression (Figure 12), as a result of wave erosion on the shoreface and sediment reworking during sea level rise. This model help to understand the extension of the basal conglomerate of the La Chilca Formation in Central Precordillera, as well as its lithofacies change and high textural maturity.

Some considerations on the tec-to-sedimentary evolution of the Hir-nantian-Silurian succession of the San Juan Precordillera.

A possible diachronism of the base of the La Chilca Formation, based on bra-chiopods record, is suggested by Benedetto and Cocks (2009), as a result of the Tambolar Arch uplift (in the sense of Heim, 1952),which will be also responsible for thickness variations and could have influenced the facies trends of the Hirnantian-Silurian succession (Benedetto and Franciosi, 1998; Peralta 2013). These facies trend is evidenced from the Cerro La Chil-ca -Talacasto range towards the South in the San Juan River area, as well also from the Cerro La Chilca and Talacasto-La Dehesa ranges (eastern proximal area) toward the La Invernada range (western distal area) (Peralta 2007, figure 1).

In the studied sections, both the chert clasts conglomerate (lithofacies A1) as the Fe-phosphate pseudo-conglomerate (lithofa-cies A2), demonstrate to be stratigraphic correlatives, being both immediately below of the Hirnantian M.persculptus Zone, such as in the Los Baños, Quebrada Ancha and Poblete Norte sections. The lateral facies change of the stratigraphic correlatives lithofacies A1 and A2 at the Talacasto area, could be attributed to the Tambolar Arch uplift, as in the rest of the Central Precordillera.

The thickening-coarsening up-ward sequence arrangement of both La Chilca and Los Espejos formations, is considered by Peralta (2007) as the result of forced regression events into an extensional regime, owing to the tilting and consequent basin deepening towards north, as proposed by Benedetto and Franciosi (1998), Benedetto and Cocks (2009) and Peralta (2013). This scenario would have favored the development of horst and graben structures, as well also the tectosedimentary environment for the basin infilling (Peralta, 2007). A similar model is proposed by San-tantonio (1994) for the Middle Jurassic in the Apennine basin, as well as by Astini et al. (1995) and Peralta and Rosales (2007) for the Middle-Upper Ordovician basin of Precordillera.

The northwards deepening of the Hir-nantian-Silurian basin and consequent shallowing towards the Tambolar arch (Peralta et al, 1997; Benedetto and Franciosi, 1998; Peralta, 2013), is supported by the record of the Leangella Fauna of late Wenlock age (Benedetto and Franciosi, 1998), in the Pachaco section at the San Juan River. In addition, the ichnofacies distribution from shallow (Tambolar area) to deeper (Jachal area) facies support this model (Peralta and Carter, 1990; Peralta et al, 1997; Peralta 2013), in opposition to that model suggested by Astini and Maretto (1996).

Besides, the emergence of the Tambolar arch might have caused the erosive surface at the base of the La Chilca, Los Bretes and Tambolar Formations (Peralta, 2013), as well also, the stratigraphic hiatus spanning the Middle to Upper Ordovician, between San Juan and La Chilca formations and their correlatives. On the other hand, the erosional process due to the Hirnantian transgression could have modified the relief, increasing the hiatus as a consequence of an irregular topography as result of the extensional tectonic regime (Peralta, 2007).

Conclusions

At the Talacasto area, in the basal strata of the La Chilca Formation., three lithofacies were recognized:

Lithofacies A1, represented by the basal conglomerate composed of two amalgamated beds, related to the base and top of the berm deposit, which is interpreted as a lag deposit onto a ravinement surface (wRs), developed on the shoreface, in a layered gravelly beach setting, dominated by storm wave process. This lithofacies is not observed at the Poblete Norte

Lithofacies A2. It is only exposed in the Poblete Norte section, at the base of the La Chilca Formation. Is composed of aFe-phos-phate pseudo-conglomerate, for which a condensation process is suggested. Compositional and textural analysis of Lithofacies A2, indicate a phosphate lag, also related to a ravinement surface (wRs).

According to their stratigraphic relationship, in the Talacasto area the lithofacies A1 and A2, are correlative and represent lateral facies change of the basal strata of the La Chilca Formation.

Lithofacies B, composed of oolitic sandstone beds, which is divided into two subfacies; Subfacies B1, composed of ooids quartz sandstone and iron-rich oolites beds, overlain the conglomerate and is interpreted as deposited in a hydrodynamically active shoreface environment. Subfacies B2, composed of iron-rich oolite as a result of a syn-sedimentary process, in a shallow coastal environment.

In the Talacasto area, the basal conglomerate (lithofacies A1), the Fe-phosphate pseudo-conglomerate, the oolitic sandstone facies, and the richly-graptolite black shale facies, are thought as the result of the Hirnantian-Rhu-ddanian post-glacial transgressive event. This event is registered by two pulses: the first one represented by the lithofacies A1 and A2, and the second one by the overlaying Fe-phosphate oolites sandstone (lithofacies B), but also by the overlaying richly-graptolite Hirnantian-Rhud-danian pelites.

The emergence of the Tambolar Arch, drove to the structural evolution of the Hirnan-tian-Silurian basin of Precordillera, controlling the topography, depositional area of the basal strata, facies trend and acting also as a local source of clastic supply.

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our gratitude to the Institute of Geology (INGEO), Faculty of Exact, Physical and Natural Sciences, National University of San Juan, and also to CIGEOBIO (CONICET-FCEFN, UNSJ). To the colleagues of the Petrography Lab of CIGEOBIO and INGEO, Paolo Ferrarini and Gladys Palacio Valderramo. Technician Vicente Mulet, CONI-CET-CIGEOBIO and INGEO, who greatly helped with the graphics. This work has been founded by CICITCA-UNSJ Code 21 / E1074.