Introduction

Fasciolosis is a zoonotic parasitic disease caused by the trematode Fasciola hepatica, distributed worldwide and affecting several animal species, including humans (Giraldo et al. 2016, León-Gallardo and Benítez 2018, Perea-Fuentes et al. 2018). Its main means of transmission is contaminated pasture consumed by animals during grazing in areas with constant humidity and the presence of the intermediate host, mollusks of the genus Lymnaea (Alpízar et al. 2013, López-Villacís et al. 2017). This disease is considered of great importance in cattle and other domestic animals since its presence causes important economic losses for the livestock production sector due to reduced weight gain, poor condition of the meat and seizure of livers, as well as public health problems (Alpízar et al. 2013, Novobilský et al. 2015).

In Peru, the distribution of F. hepatica has been reported in 17 of the 24 regions, being Cajamarca the one with a prevalence of 80% in cattle and is considered among the highest (SENASA 2007, Ortiz 2011, Valderrama 2016). Thus, in a study they reported that with a 49% decrease in the initial prevalence of fasciolosis in cattle, an increase of 38% in weight and 75% in milk production can be achieved by dosing the animals with trematocides, cleaning the irrigation canals and modifying the inclination angles from 90° to 130° (Raunelli and Gonzalez 2009).

It is important to recognize that the population of the Andean zones is mainly dedicated to agricultural activities, cultivating large extensions of land during the wet or rainy season and to a lesser extent under artificial irrigation during the dry season (Pajares 2010). To this end, access to water in the highlands is mostly through springs and irrigation canals, although their management and use is inefficient, favoring the transmission of parasitic diseases and other contaminants (Choque-Quispe et al. 2021, Lund et al. 2021). It is at this point where the precarious distribution of water resources in the Cajamarca region becomes important with the presence of highly competent intermediate hosts which are snails of the Galba truncatula and Pseudosuccinea columella species; G. truncatula being the one that increases its transmissibility at an altitude above 2000 m.a.s.l. with longer periods of production and elimination of cercariae (Bardales-Valdivia et al. 2021).

All this epidemiological synergy of fasciolosis requires a prompt update, especially due to the rapid advance of resistance to anthelmintics and the greater adaptation of the parasite to the climatic conditions of the Peruvian Andes. It is also important to take into account the economic damage due to seizures of livers damaged by F. hepatica, which generate annual losses of US$ 50 million at the national level and US$ 230 million in the Cajamarca region (León-Gallardo and Benítez 2018).

Although the most widespread form of prophylaxis is proper management, it is necessary to analyze the relationship of the irrigation systems used for pasture cultivation in the control of fasciolosis in bovines. Therefore, the present research aimed to demonstrate the influence of the type of traditional irrigation (flooding) and technified irrigation (sprinkling) on the prevalence of bovine fasciolosis in two cattle units located in the province of San Marcos, Cajamarca region, Peru.

Materials and methods

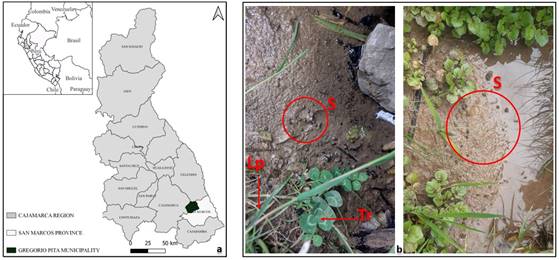

Population and location. The study was conducted in dairy cattle of the Holstein and Brown Swiss breeds from northern Peru, recently introduced in two livestock units dedicated to dairy production, in extensive type breeding in two communities of the municipality of Gregorio Pita located in the coordinates with latitude -7.1537 and longitude -78.1332 of the province of San Marcos, Cajamarca region, between the months of March and December 2015 (Figure 1a). The area is located at an altitude of 2770.51 m and has a tropical dry climate, reaches an annual average maximum temperature of 26.34°C and minimum of 3.72°C, the relative humidity is 72.44% and rainfall is 1.33 mm/day or 486.27 mm in the year (Data provided by the Servicio Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología del Perú). In the two selected farms, the presence of the intermediate host G. truncatula was verified, although in the farm with sprinkler irrigation, the animals did not have access to the irrigation ditches, which only served the purpose of draining rainwater (Figure 1b).

Figure 1 Map showing the location of the municipality of Gregorio Pita within Cajamarca region, Peru (a). Farm ditches used for traditional irrigation or rainwater drainage, the following can be observed: S = snails, Lp = Lolium perenne and Tr = Trifolium repens (b).

Animal selection. During the months of January and February, the newly introduced animals older than one year of age were adapted to their new locations and husbandry system Fecal samples were collected to rule out the presence of F. hepatica and the animals were grouped according to their unit of origin: group 1 (G1) consisted of 10 bovines fed on rye-grass (Lolium perenne) / clover (Trifolium repens) grown with traditional or flood irrigation and group 2 (G2) consisted of 10 bovines also fed on rye-grass (Lolium perenne) / clover (Trifolium repens) grown with sprinkler irrigation.

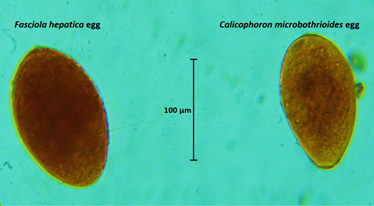

Sampling and coproparasitological study. Once the negativity of the cattle to the parasite was confirmed, from March onwards, samples were taken directly from the rectum of each animal, approximately 100 g of feces in the morning, and were transferred to the Laboratory of Veterinary Parasitology and Parasitic Diseases of the Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias, Universidad Nacional de Cajamarca for their respective analysis. The coproparasitological analyses of the 20 samples were performed monthly for ten consecutive months with Rapid Sedimentation following the technique described by Lumbreras et al. (1962). Parasitological 5% Lugol's solution was used to differentiate the eggs of Fasciola hepatica and Calicophoron microbothrioides using a stereoscope at 4X and to confirm the appropriate genus was observed with a 10X objective in an optical microscope (Figure 2).

Data analysis and processing. The data obtained were expressed as "positive" for cattle with the presence of F. hepatica eggs in the faeces and "negative" when these parasitic forms were absent. In addition, Microsoft Excel 2019 Professional was used to run Fisher's test to determine if there is an association between the prevalence of fasciolosis and the type of irrigation.

Ethical considerations. This study was conducted within the framework of the Ley de Protección y Bienestar Animal 30407 in force in the Peruvian State. Before initiating the research, the protocol was reviewed and approved by the Comité Ético de Uso de Animales of the Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias of the Universidad Nacional de Cajamarca. The animals were not harmed during the study process.

Results and discussion

The positive findings to coproparasitology allow us to calculate the prevalence of fasciolosis in G1, which used traditional or flood irrigation, with 60% of the total infected animals, compared to the prevalence observed in G2, which used sprinkler irrigation, with 20% of the animals releasing eggs through the faeces in the period studied (Table 1 and Figure 2). However, statistically, there is not enough evidence to affirm that the prevalence of fasciolosis is related to the type of irrigation used in pasture farming (p>0.05), probably due to the size of the sample or to the high endemicity of the parasite in this area of northern Peru.

Table 1: Monthly and overall prevalence of fasciolosis in dairy cattle according to type of irrigation.

Figure 2 Eggs found by coproparasitology and observed at 10X with parasitological 5% Lugol's solution.

The difference between the prevalences obtained could be due to the presence of factors that make possible the development of the latent infectious form of F. hepatica in each livestock unit, such as the constant humidity in the cultivation areas, the environmental temperature above 10°C, and the presence of competent intermediate hosts such as G. truncatula in irrigation canals, swamps, irrigation ditches, stagnant waters, streams, ponds, also in the soil and plants close to fresh water catchments detected in both groups of studies located within the province of San Marcos, Cajamarca region, in addition to the influence of the altitude of this area (Novobilský et al. 2015, Bardales-Valdivia et al. 2021).

Altitudes between 2007 - 3473 m.a.s.l., together with climatic seasonality directly influence the snail population, as in the case of G. truncatula in temporarily dry habitats, while humid habitats such as those generated during the rainy periods in the Peruvian highlands that coincide with the summer season, as well as the use of traditional irrigation (by flooding) in the dry season, make it possible for the biological cycle of F. hepatica to be completed and subsequently the animals come into direct contact with the infecting parasitic form; finding all these meteorological characteristics in G1, likewise, promote a higher prevalence (Bardales-Valdivia et al. 2021). Another more complete epidemiological study developed in Cajamarca concludes that the months between December and May are environmentally optimal for the acquisition of new infections or reinfections by F. hepatica, and the maximum excretion of eggs occurs between August and September (Claxton et al. 1997), thus corroborating the present investigation with the appearance of the first positive cases in that period.

On the other hand, based on research carried out in other regions of Peru and other countries, fasciolosis in both sheep and cattle occurs with high frequencies, probably due to the type of feed consumed, especially when the animals are raised in open, natural pastures or sown with alfalfa or other grasses (Jara et al. 2018).

Thus, in the Amazon region, an overall prevalence of F. hepatica of 59.5% in cattle, with a higher prevalence in the districts of Yambrasbamba and Florida (Julon et al. 2020); in two places in La Libertad (Pataz and Otuzco), high prevalence has also been reported, 62.4% and 74.3%, respectively (Jara et al. 2018, León-Gallardo and Benítez 2018). Likewise, it has been reported in several studies around the world in dairy cattle, such as Colombia (12.3%) (Giraldo et al. 2016) and more than 50% in samples taken from dairy cattle during the rainy season in the province of Matanza, Cuba (Soca-Pérez et al. 2016); It is necessary to emphasize that in all the studies the coprological method was used to determine the prevalence of fasciolosis and the sampled animals were raised extensively, so they consume short stem plants cultivated mainly under the traditional system of rains and irrigation, as well as the sample of this study.

Conclusions

There is statistical evidence that the prevalence of fasciolosis in cattle in this controlled experiment is not related to the type of irrigation used in the pasture culture. Despite this, a greater impact is seen in animals fed flood-irrigated rye grass/clover where prevalence was higher compared to individuals fed sprinkler-irrigated pasture. It is recommended to increase the sample size, consider other more specific diagnostic methods and include environmental and seasonal behavioral variables of the intermediate host for further studies in order to extrapolate the results to the cattle population of Cajamarca, Peru, and other regions of the world.