Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista argentina de cirugía

versão impressa ISSN 2250-639Xversão On-line ISSN 2250-639X

Rev. argent. cir. vol.114 no.2 Cap. Fed. jun. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.25132/raac.v114.n2.1584

Articles

Minimally invasive management of blunt hepatic trauma complications

1 Servicio de Cirugía General Hospital Mu nicipal de Agudos Dr. Leónidas Lucero. Buenos Aires. Argentina.

Introduction

Nonoperative management (NOM) of blunt hepatic trauma is feasible in more than 95% of hemodynamically stable patients with mild-grade to severe-grade injuries1-3.

The overall rate of complications of hepatic trauma is 7%4. Complications in high-grade liver injuries (groups III, IV and V of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma [AAST] classification) occur in 14% of the cases and can be predicted by the injury grade and the volume of transfusions required at 24 hours postinjury5,6.

Late bleeding (72 h after liver trauma) is the most common complication in up to 3% of the cases. Then, between 2.8% and 7.4% develop biliary complications. Biloma, ischemia of the liver and gallbladder and liver abscesses are the most common complications7.

When these complications require surgical management via laparotomy, mortality reaches 27%.

Hepatic trauma is an infrequent cause of liver abscess, constituting < 5% of all the cases reported. The incidence of liver abscess as a complication of NOM of blunt hepatic trauma is 1.5%, particularly in high-grade injuries9.

Depending on the location, extent and size, liver abscesses can be treated with antibiotic therapy with or without drainage using imaging guidance, or through laparoscopy, endoscopy, or rarely laparotomy.

Nowadays, the use of laparoscopy for the management of trauma is well documented, as in most abdominal conditions. The benefits of early diagnostic and therapeutic laparoscopy for mesenteric, solid organ and hollow viscus injuries have been reported in large centers10. The aim of this report is to describe the minimally invasive management of the complications of blunt hepatic trauma.

Material and methods

We included patients > 15 years with blunt hepatic trauma requiring minimally invasive abdominal interventions between October 1, 2018, and September 30, 2019. The medical records and the electronic database were reviewed, and the cases were described.

Results

We report three cases and the minimally invasive management used.

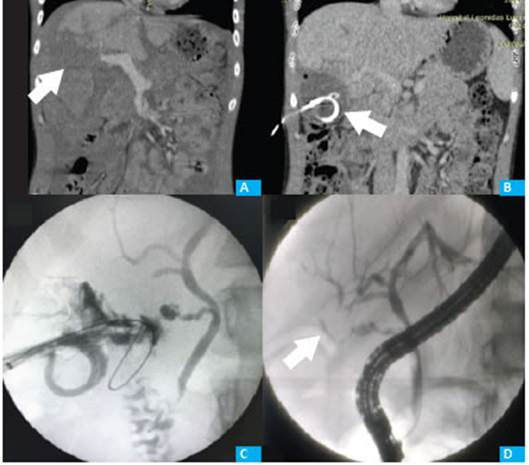

Case “A”: a 28-year-old male patient admitted after a collision between two motorcycles; Glasgow score 5/15; free peritoneal fluid on focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST). Multislice computed tomography (CT) scan: grade IV hepatic trauma asso ciated with fractures of the bones of the face. ISS 16 (Fig. 1 A). The patient was hemodynamically stable and NOM was initiated. Forty-eight hours later, the patient remained hemodynamically stable but presented pa ralytic ileus and underwent exploratory laparoscopy which showed extensive hemoperitoneum and hema toma in liver segments V and VI, without biliary leak or other associated lesions. Laparoscopic lavage and drai nage of the cavity were performed. On postoperative day 1, the patient presented low-output bile leak from the drainage catheter. The patient had favorable outco me and was discharged with the drain due to persistent bile leak 25 days after the trauma. Seven days later he sought medical care due to fever and purulent draina ge. The CT scan showed a liver abscess in segments V and VI that was percutaneously drained using a 10.2 Fr catheter under CT guidance (Fig. 1B). The culture was positive for Acinetobacter baumanii and Enterococcus faecalis. A second drain was placed due to persistent fluid collection. The drainage catheter was successively replaced and finally a 32 Fr catheter was inserted (Fig. 1C). The cavitography revealed communication with the bile ducts and persistent biliary fistula. An endos copic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) detected a leak through the cystic duct, with intact in trahepatic biliary tract. A 10 Fr, 10 cm plastic stent was placed (Fig. 1D).

The purulent leakage decreased. Four weeks after the last catheter was replaced, the patient had a favorable response in clinical and imaging-based signs.

Figure 1 A: Hematoma and laceration involving almost the entire right hepatic lobe, measuring approximately 110 mm, consistent with a grade IV liver injury according to AAST classification (arrow). Moderate fluid around the liver, spleen and in the Douglas’ pouch. B: Collection with air bubble of 50 × 30 mm in liver segment IV with percutaneous drainage (arrow). C: Cavitography through the drain placed in liver segment V showing communication with the bile ducts. D: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP): bile duct with contrast leak through the cystic duct (arrow).

Case “B”: a 26-year-old male patient was admit ted after a collision between a motorcycle and a truck; Glasgow score 5/15; free peritoneal fluid on FAST. Mul tislice CT scan: grade III hepatic trauma is segments V and VIII associated with bilateral lung contusion. ISS 17 (Fig. 2A). As the patient was hemodynamically stable, damage control surgery was performed. The laparosto ma was closed 48 hours later without liver resection. The patient evolved with fever and the imaging tests showed an image suggestive of liver abscess which was percutaneously drained using a 10.2 Fr catheter under CT guidance (Fig. 2B). Purulent bile drained through the catheter. The culture was negative. The patient had fa vorable outcome and was discharged with the drain 35 days after the trauma. During follow-up in the outpa tient clinic, a CT scan showed persistent fluid collection. The drainage catheter was replaced due to persistent abscess. Four weeks later the patient had a favorable response in clinical and imaging-based signs (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2 A: Large intraparenchymal hematoma predominating in segments V and VIII of the right liver lobe, measuring up to 100 mm in its major transverse axis, consistent with grade III liver injury according to the AAST classification (arrow). B: An organized hematoma measuring 125 × 64 × 62 mm is observed in segments V and VIII. C: Drainage catheter placed in the completely evacuated collection (arrow). The rest of the parenchyma is homogeneous.

Case “C”: a 19-year-old male patient was ad mitted after a collision between a motorcycle and a car; free peritoneal fluid on FAST. Multislice CT scan: grade IV liver laceration associated with right lung contusion (Fig. 3A). ISS 16. Hemodynamic stability was achieved after crystalloid infusion and transfusion of blood pro ducts. NOM was initiated.

On day 9 after admission, the patient presented fever and abdominal pain, and exploratory laparoscopy was decided. Laparoscopic lavage and drainage were performed due to extensive hemoperitoneum without bilious fluid. As fever persisted on postoperative day 6, the patient underwent a CT scan and percutaneous drainage of an intraparenchymal hematoma with a 10.2 Fr catheter under CT guidance with evacuation of bilious and hematic fluid (Fig. 3B). The patient had a favorable outcome, and the culture of the fluid was negative. The patient was discharged with purulent output. Three weeks later, a CT scan performed on an outpatient basis showed a residual subphrenic collection. The drainage catheter was replaced by a 14 Fr catheter (Fig. 3C). Three weeks later the patient had a favorable response in clinical and imaging-based signs.

Figure 3 A: Grade IV injury of AAST. Intraparenchymal hematoma involving more than 75% of the right lobe and lack of visualization of the right suprahepatic vein and of the anterolateral border of the inferior vena cava behind the liver. B: Hypodense image in liver segments VI-VII consistent with intraparenchymal hematoma (arrow). C: Drainage catheter entering the right hypochondrium towards the ipsilateral hepatic lobe where a heterogeneous fluid collection from the right lobe is observed.

Discussion

The management of high-grade liver trauma represents a challenge in the emergency room, intensive care unit and operating room. As these traumas are usually of high impact, they generally involve patients with multiple associated injuries with high mortality. Nonoperative management is based on the “second hit” concept of emergency surgery and on the evidence of its efficacy and safety in experienced tertiary care centers. However, liver complications do not strictly depend on choosing damage control surgery or nonoperative management, but they rather appear after the acute phase of trauma, which allows a minimally invasive management3,6,11.

Laparoscopy is used in the treatment of abdominal trauma; however, there are no clear recommendations due to the lack of controlled trials. In patients with blunt trauma, the recommendations are even less clear. Laparoscopy offers benefits in selected situations, as in patients with fluid collections of unknown origin, when there is suspicion of hollow viscus injury, mesenteric injury, or for symptomatic hemoperitoneum4,12,13.

Liver resection was not necessary in any of the cases reported. Two patients underwent diagnostic laparoscopy and drainage of the peritoneal cavity. The scheduled replacement of percutaneous drains is a rule for this type of hepatic abscesses. Persistent biliary fistulas are not uncommon, and endoscopic drainage plays a decisive role for timely and efficient treatment. As in other series, our cases did not present morbidity or mortality associated with minimally invasive treatments, representing a safe approach for the treatment of this condition in centers with experience in trauma and liver surgery.

Multiple series have demonstrated that percutaneous drainage is a safe strategy for the treatment of liver abscesses, reaching 95% efficacy in some reports13,14. Minimally invasive strategies are currently considered the standard of care for the management of complications of blunt liver trauma, including bilomas, active bleeding, hematomas and abscesses7.

The minimally invasive techniques used for these cases require a multidisciplinary and qualified team with the necessary materials, instruments and CT scan, laparoscopy, endoscopy and radioscopy capabilities.

Referencias bibliográficas /References

1. Meredith JW, Young JS, Bowing J, Roboussin D. Nonoperative management of blunt hepatic trauma: the exception to the rule? J Trauma. 1994;36:529-34. [ Links ]

2. Pachter HL, Knudson MM, Esrig B, et al. Status of nonoperative management of blunt hepatic injuries in 1995: a multicenter experience with 404 patients. J Trauma. 1996;40(1):31-8. [ Links ]

3. Coccolini F, et al. Liver trauma: WSES position paper. World J Emerg Surg 2015; 10:39. [ Links ]

4. Kozar RA, Moore JB, Niles SE, et al. Complications of nonoperative management of high-grade blunt hepatic injuries. J Trauma. 2005;59(5):1066-71. [ Links ]

5. Kozar RA, Moore FA, Cothren CC, Moore EE, Sena M, Bulger EM, et al. Risk factors for hepatic morbidity following nonoperative management: multicenter study. Arch Surg. 2006;141:451-8. [ Links ]

6. Kozar RA, Moore FA, Moore EE, et al. Western Trauma Association critical decisions in trauma: nonoperative management of adult blunt hepatic trauma. J Trauma. 2009;67(6):1144-9. [ Links ]

7. Bala M, et al. Complications of high grade liver injuries: management and outcome with focus on bile leaks. Scand J Trauma Resus 2012;20:20. [ Links ]

8. Mohr AM, et al. Angiographic embolization for liver injuries; low mortality, high morbidity. J Trauma. 2003;55:1077-82. [ Links ]

9. Hsieh CH, et al. Liver abscess after non-operative management of blunt liver injury. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2003;387:343-7. [ Links ]

10. Carrillo EH, Wohltmann C, Richardson JD, Polk Jr HC. Evolution in the treatment of complex blunt liver injuries. Curr Probl Surg. 2001;38:1-60. [ Links ]

11. Tschoeke SK, Hellmuth M, Hostmann A, Ertel W, Oberholzer A. The early second hit in trauma management augments the proinflammatory immune response to multiple injuries. J Trauma. 2007;62(6):1396-404. [ Links ]

12. Letoublon C, Chen Y, Arvieux C, Voirin D, Morra I, Broux C, et al. Delayed celiotomy or laparoscopy as part of the nonoperative management of blunt hepatic trauma. Worls J Surg. 2008;32:1189- 93. [ Links ]

13. Haider SJ, Tarulli M, McNulty NJ, Hoffer EK. Liver Abscesses: Factors That Influence Outcome of Percutaneous Drainage. Am J Roentgenol. 2017;209:205-13. [ Links ]

14. Acquafresca P, Palermo M, Houghton E, Finger C, Giménez M. Tratamiento mini-invasivo de una lesión hepática pos-traumatismo cerrado de abdomen. Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam. 2016;46:220-2. [ Links ]

Received: March 25, 2021; Accepted: June 11, 2021

texto em

texto em